| Case Report | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14(7): 1708-1715 Open Veterinary Journal, (2024), Vol. 14(7): 1708–1715 Case Report Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomyDanilo C. Sousa1, Ygor A. Rossi2, Luíz G. D. Benevenuto3, Carlos E. Fonseca-Alves3,4,5, Larissa F. Magalhães6, Cynthia M. Bueno7 and Denner S. Dos Anjos3*1Veterinary Medicine, Universidade de Franca (UNIFRAN), Franca, São Paulo, Brazil 2Veterinary Surgery, Veterinary Hospital, Universidade de Franca (UNIFRAN), Franca, São Paulo, Brazil 3Department of Veterinary Surgery and Animal Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science (FMVZ), São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu, Brazil 4Institute of Health Sciences, Universidade Paulista (UNIP), Bauru, São Paulo, Brazil 5Institute of Veterinary Oncology – IOVET-SP, São Paulo, Brazil 6LM Diagnosis of Veterinary Pathology, Uberlândia, Brazil 7Private Clinic CEMA, Batatais, São Paulo, Brazil *Corresponding Author: Denner S. Dos Anjos. Department of Veterinary Surgery and Animal Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science (FMVZ), São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu, Brazil. Email: denner.anjosoncology [at] gmail.com Submitted: 01/04/2023 Accepted: 03/06/2024 Published: 31/07/2024 © 2024 Open Veterinary Journal

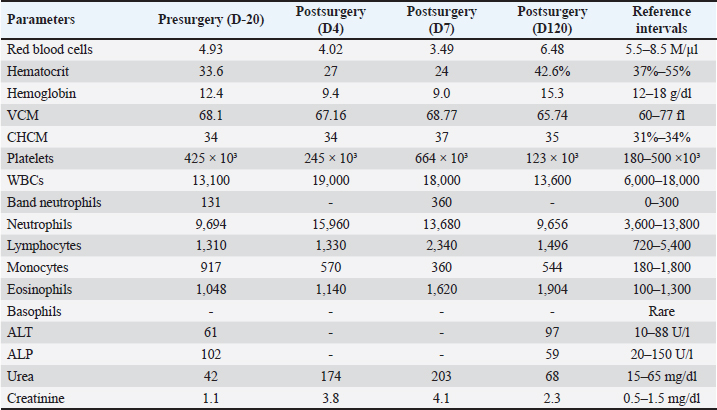

AbstractBackground: Primary ureteral neoplasms are extremely rare in dogs, and ureteral involvement usually occurs owing to the invasion of renal and bladder tumors. Case Description: This case report describes a 12-year-old intact male mixed-breed dog referred to a private clinic with a six-month history of abdominal distention. A physical examination revealed mild abdominal pain. Hematological tests detected normocytic-normochromic anemia (hematocrit 33.6% [reference interval-RI: 37%–55%], red blood cells 4.93 M/µl [RI: 5.5–8.5 M/µl], and hemoglobin 12.4 g/dl [RI: 12–18.0 g/dl]). The results from the leukogram, thrombogram, renal, and hepatic panels were within the reference intervals for dogs. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a cavitary mass measuring approximately 12 cm in diameter as the largest tumor in the left abdominal region over the left hepatic lobe or mesenteric site. Chest radiography did not reveal any metastasis. Therefore, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, during which the left ureter was found to be affected by a 12-cm mass that adhered to the left kidney. A unilateral left ureteronephrectomy was performed, and histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirmed well-differentiated primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma. The patient survived for 130 days but died of lung metastasis. Conclusion: Ureteral leiomyosarcoma should be investigated and included in the list of differential diagnoses for primary ureteral neoplasms. Regardless of the therapeutic modality, the prognosis of ureteral leiomyosarcoma may be unfavorable, as shown in this report. Keywords: Leiomyosarcoma, Dogs, Ureteral neoplasm, Ureteronephrectomy. IntroductionPrimary ureteral neoplasms are extremely rare in dogs (Johnston and Tobias 2018; Meuten, 2002). Ureteral involvement is most commonly caused by renal and bladder tumor invasion (Liska and Patnaik, 1977; Berzon, 1979). The clinical manifestations include polyuria, polydipsia, pollakiuria, hematuria, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infection. However, in some cases, clinical signs such as apathy, abdominal pain, emesis, and pyrexia may not be specific to the urinary tract (Liska and Patnaik, 1977; Font et al., 1993; Deschamps et al., 2007). The treatment of choice for primary ureteral neoplasms is surgical resection through unilateral ureteronephrectomy or ureterectomy combined with ureteral anastomosis (Kulkarni & Bellamy, 2001; Berent et al., 2007; Guilherme et al., 2007; Troiano & Zarelli, 2017), with this previous approach being a surgical challenge owing to the risk of urinary leakage and ureteral stenosis (Yap et al., 2017). Benign ureteral neoplasms have a good prognosis after surgical excision (Liska & Patnaik, 1977; Font et al., 1993). However, it is poor for malignant tumors because of the risk of recurrence and distant metastasis (Berzon, 1979; Deschamps et al., 2007; Guilherme et al., 2007). Herein, we report a rare case of primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma in a senile dog and describe its clinical, surgical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical features. Case DetailsThe animal was client-owned and written informed consent was obtained from the owner. A 12-year-old intact male mixed-breed dog was referred to an oncologist in a private clinic (Central Pet, Orlândia, São Paulo) with a six-month history of abdominal distention. During these six months, the patient underwent two abdominal ultrasound evaluations, and a mass of approximately 12 cm was observed in the largest tumor diameter in the left abdominal region over the left hepatic lobe or mesenteric site. The owner observed the first instance of abdominal distention 6 months before the oncology consultation. Three months after the initial observation, the patient had one complete blood count (CBC), which revealed mild initial anemia, hematocrit 36.8% (Reference intervals-RI: 37%–55%), red blood cells 5.48 M/µl (RI: 5.5–8.5 M/µl), and hemoglobin 13.0 g/dl (RI: 12–18 g/dl). Based on the patient’s medical history, the owner did not notice any urinary abnormalities related to urine, dysuria, or hematuria. Although the owner leash walked the dog to urinate, there was no direct observation of the dog during the day to confirm that the dog did not have signaling-related abnormalities in the urinary tract. Another limitation was the absence of a complete urinalysis performed in the clinic before surgery. However, the owner decided to perform follow-up blood tests and imaging and did not accept initial abdominal exploratory laparotomy. Physical examination revealed mild abdominal pain and pale mucous membranes. Pulse, respiratory, heart rates, and rectal temperature were unremarkable and within the RI for the species. At the initial presentation (three months before the consultation), the patient had a history of anemia, as reported above. Blood tests were performed, and the CBC was suggestive of nonregenerative normocytic-normochromic anemia with hematocrit 33.6% (RI: 37%–55%), red blood cells 4.93 M/µl (RI: 5.5–8.5 M/µl), and hemoglobin 12.4 g/dl (RI: 12–18 g/dl). However, a reticulocyte count was not performed, precluding the determination of whether there was non-regenerative or regenerative anemia. Leukograms, platelet counts, and biochemical evaluations, including measurements of creatinine, urea, alkaline phosphatase, and alanine aminotransferase, were within the RI for the species (Table 1). Unfortunately, a complete urinalysis was not performed at the clinic. Additional ultrasonography and radiography showed a large cavitary mass measuring approximately 12 cm in the left mid-abdominal region. Thoracic radiography did not reveal any obvious metastases. The importance of the surgical procedure for treatment was explained to the owner, and exploratory laparotomy was performed 20 days after the examination (defined as D-20 in Table 1) (Fig. 1). Following suspicion of a liver or mesenteric tumor, the patient was referred for laparotomy. During the surgical procedure, an enlarged mass was observed adhering to the left kidney, with the liver and spleen intact. For resection, a unilateral left ureteronephrectomy was performed. The patient experienced intense perioperative blood loss and hypotension. After whole-blood transfusion during the perioperative period, the vital parameters returned to normal. Table 1. Hematological and biochemical analysis of a dog diagnosed with well-differentiated leiomyosarcoma.

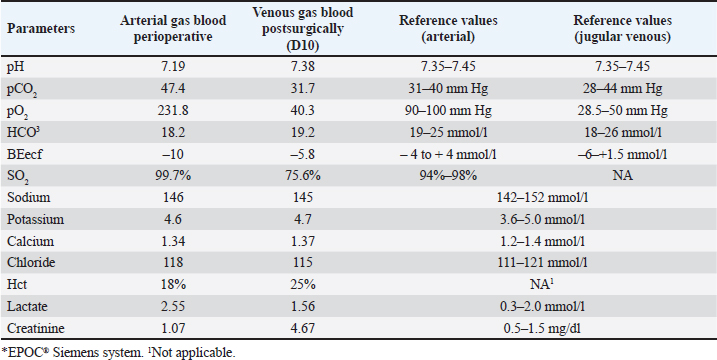

Fig. 1. Exploratory laparotomy in a mixed-breed dog showing a large mass measuring approximately 12 cm in the largest tumor diameter in the left abdominal region over the left hepatic lobe or mesenteric site. Blood gas analysis was performed perioperatively from the dorsal metatarsal artery on the left hind limb (arterial) and 10 days after surgery through the jugular venous blood (venous) (Table 2). Arterial blood gas results in metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis, categorizing a mixed acid-base disturbance, since the compensatory response for primary metabolic acidosis is respiratory alkalosis. The presence of hypercapnia, defined as a PCO2 greater than 42 mmHg, could suggest hypoventilation/decreased tissue perfusion (lactic acidosis) that was treated by increasing effective alveolar ventilation in addition to supplemental oxygen, with hemodynamic stability optimized to resolve hypercapnia secondary to poor pulmonary perfusion, including whole-blood transfusion. After surgery, the patient was discharged on enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg, twice daily, per os [PO] for seven days), meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg, once daily, PO for five days), tramadol hydrochloride (5 mg/kg, q 8 h, PO for five days), dipyrone (25 mg/kg, q 8 h, PO for five days), and omeprazole (1 mg/kg, twice daily, PO for seven days). One week following unilateral left ureteronephrectomy, azotemia was observed (creatinine 4.1 mg/dl [RI: 0.5–1.5 mg/dl] and urea 203 mg/dl [RI: 15–65 mg/dl]), and treatment with intravenous fluid therapy (Lactated Ringer’s solution) was administered for one week at a maintenance fluid rate of 2 ml/kg/hr. Unfortunately, a complete urinalysis was not performed in the clinic to fully stage the patient for possible chronic kidney disease. Afterward, creatinine decreased to 3.0 mg/dl (RI: 0.5–1.5 mg/dl) and urea to 130 mg/dl (RI: 15–65 mg/dl), and the patient was discharged. In the last parameter (D120) during follow-up, the creatinine level was 2.3 mg/dl (RI: 0.5–1.5 mg/dl), and that of urea was 68 mg/dl (RI: 15–65 mg/dl) (Table 1). The owner did not notice any abnormalities in the patient’s urine at home. The patient was rechecked monthly for hematological and renal abnormalities after being placed on a renal diet. The owner refused adjuvant chemotherapy. The patient was active and had gained weight during the three months of follow-up. Table 2. Canine blood gas parameters in the perioperative and postsurgical analysis*.

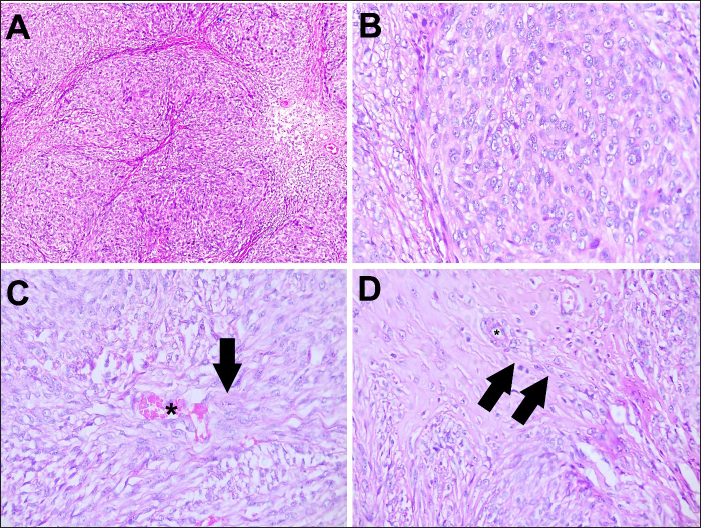

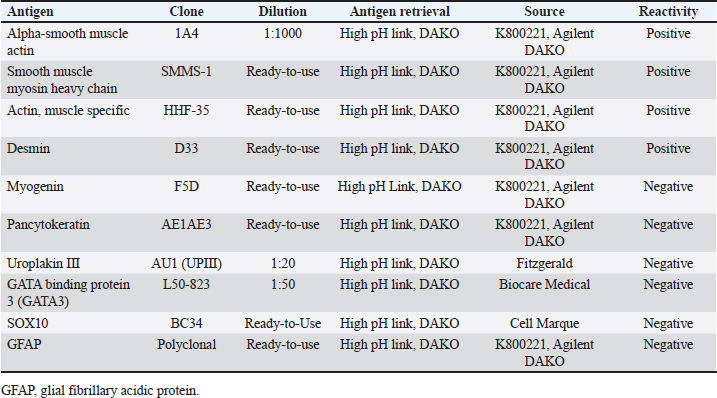

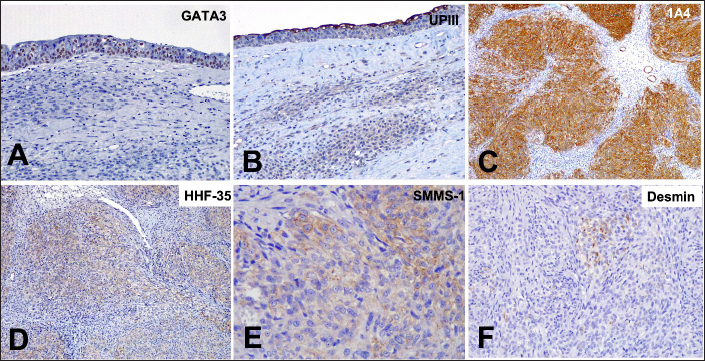

Histopathology revealed that the left kidney had glomerular capsule thickening, discrete and multifocal interstitial lymphocytes, moderate tubular dilation, a small number of hyaline casts, and a slight amount of tubular calcification. No neoplastic cells were observed. In addition, the large mass was characterized by diffuse malignant neoplastic mesenchymal cell proliferation with necrotic areas arranged in dense bundles separated by the stroma (Fig. 2). The cells exhibited moderate anisocariosis with evident nucleoli. The cells were characterized by an eosinophilic cytoplasm, poorly delimited, and sometimes vacuolated with round to oval nuclei, loose chromatin, and small evident nucleoli. A low mitotic index (two mitoses in 10 high-power fields) was also observed. An immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel was also performed to further characterize the tumor, showing positivity for alpha-smooth muscle actin (1A4), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMS-1), and muscle-specific actin (HHF-35), and scattered positive staining for desmin (D33). Positive staining for GATA3 and UPIII was observed in the normal urothelial mucosa of the ureter. In conclusion, primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma was confirmed, and the neoplastic cells were negative for myogenin, pancytokeratin, uroplakin III, GATA-binding protein 3, SOX10, and Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Photomicrographs of a canine ureteral leiomyosarcoma hematoxylin and eosin stanning. (A) Lower magnification of neoplastic cells showing a mesenchymal cell proliferation, with areas of necrosis. HE, 10x. (B) Higher magnification of a malignant diffuse mesenchymal neoplastic cell proliferation, arranged in dense bundles, separated by stroma. Cells present a moderate anisocariosis, with evident nucleoli. HE, 40x. (C) Cells presenting eosinophilic cytoplasm, poorly delimited, sometimes vacuolized, round to oval nucleus with loose chromatin and small evident nucleolus. Examination reveals a blood vessel (asterisk) with mesenchymal malignancy and the cells invading the stroma in the direction of the blood vessel (arrow).HE, 40x. (D) Higher magnification of neoplastic cells invading tissue stroma (arrows) in the direction of blood vessels (asterisk) 40x. Table 3. Primary antibodies used in the IHC panel for primary ureteral malignant leiomyosarcoma in a mixed-breed dog.

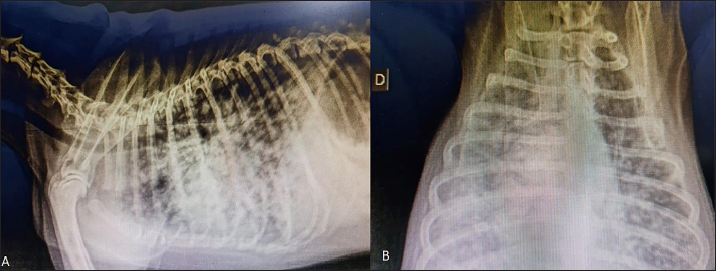

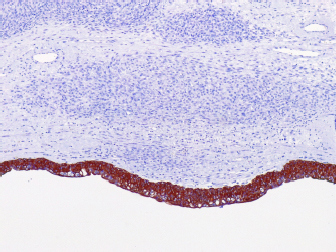

One hundred and thirty days after surgery, the patient started experiencing respiratory distress, and two-view radiographic images suggested distant metastasis (Fig. 4). Unfortunately, the patient died in the clinic and necropsy was not authorized by the owner. Ethical approvalThe work described in this manuscript involves the use of non-experimental (client-owned animals). Established internationally recognized high standards (“best practices”) of veterinary clinical care for individual patients were followed in this study. DiscussionDespite the rare incidence of ureteral neoplasms in dogs, primary leiomyosarcomas have been reported in these animals (Berzon, 1979; Yap et al., 2017). Leiomyosarcoma is a neoplasm originating from the smooth muscle that mainly affects the digestive and reproductive tracts. When it affects the urinary tract, the main site is the bladder (Berzon, 1979). In a retrospective study of 113 dogs that evaluated neoplasms of the urinary system, it was found that among the primary neoplasms, three patients had leiomyosarcomas: one in the kidney, one in the bladder, and one in the ureter, confirming that its occurrence is uncommon (Inkelmann et al., 2011). The mitotic count has been used to distinguish between benign and malignant smooth tumors in the intestinal, genital, and urinary tracts of dogs, with a mitotic index of 0.05 for leiomyoma and 1.65 for leiomyosarcoma (Johnson et al., 1995; Meuten et al., 2017). Based on these features, we considered the number of mitotic cells, in combination with other morphological features, to diagnose well-differentiated leiomyosarcoma. Similar to the findings in human medicine (Chen et al., 2008), malignant neoplasms in the urinary tract are commonly located in the distal portion of the ureter (Berzon, 1979; Hanika & Rebar, 1980; Polit et al., 2020), whereas benign neoplasms affect the proximal region (Hattel et al., 1986; Burton et al., 1994). In the present report, the ureteral leiomyosarcoma was located in the proximal ureter. The exact location of the neoplasm was obtained only through exploratory laparotomy because the abdominal ultrasound was inconclusive, and the owner declined computed tomography. Furthermore, normal urothelial mucosa in the ureter was observed by IHC for pan-cytokeratin (Fig. 5), whereas below the urothelial mucosa, mesenchymal cell proliferation was negative. In the histopathological examination, it was also possible to determine that in the kidney sample, we did not have neoplastic cells, whereas in neoplastic tumors, the intact ureter epithelium was present, indicating a urinary origin and possibly an origin from the ureteral wall, as we did not observe any other structures that would suggest neoplastic tissue originating from the kidney.

Fig. 3. Photomicrographs of a canine ureteral leiomyosarcoma. (A) Positive staining for GATA3 in normal urothelial mucosa in the ureter, 20x. (B) Staining for UPIII in normal urothelial mucosa in the ureter, 20x. (C) Positive staining for alpha-smooth muscle actin (1A4) in neoplastic cells, 10x. (D) Positive staining for muscle-specific actin, 10x. (E) Positive staining for smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, 40x. (F) Scatted positive staining for desmin, 10x. IHC, Harris hematoxylin counterstaining.

Fig. 4. Radiographic two-view projections of a canine diagnosed with ureteral well-differentiated leiomyosarcoma. (A) Latero-lateral projection showing diffuse multiple nodules in the lungs. (B) Ventrodorsal projection with diffuse multiple nodules suggestive of pulmonary metastasis. Usually, the most common clinical signs of ureteral masses include polyuria, polydipsia, pollakiuria, hematuria, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infection (Liska and Patnaik, 1977; Font et al., 1993; Deschamps et al., 2007); however, the patient in question presented abdominal pain and distension, probably owing to the large tumor volume but without systemic and/or urinary tract-related clinical signs. The signs may be minimal or nonspecific until the mass reaches a considerable size or until hydronephrosis occurs (Crow, 1985). The main differential diagnoses for ureteral leiomyosarcomas are ureteroliths and nephroliths, which can cause abdominal pain, stranguria, hematuria, and pollakiuria. In addition, benign ureteral neoplasms, abdominal masses with consequent extramural ureteral compression, and extension of renal or bladder neoplasms should be considered differential diagnoses. Therefore, any cause of abdominal pain associated with urinary tract signs should be investigated using abdominal radiography or ultrasonography. Once the presence of neoplasms is confirmed, they must be definitively diagnosed histopathologically.

Fig. 5. Photomicrographs of a canine ureteral leiomyosarcoma. (A) Positive staining for pancytokeratin (AE1AE3) in normal urothelial mucosa in the ureter with negative staining of mesenchymal cell proliferation below, 10x. The clinical signs evidenced in this report, in which the patient had intermittent urinary incontinence, differed from those previously observed (Yap et al., 2017) and those previously reported for ureteral sarcoma (Deschamps et al., 2007) which was associated with hematuria. The clinical signs in the present case also diverged from those mentioned in the human literature (Nakajima et al., 1994), in which a woman with ureteral involvement in leiomyosarcoma had hematuria. However, the patient experienced abdominal pain in all cases. Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of ureteral neoplasm treatment through unilateral ureteronephrectomy or ureterectomy associated with ureteral anastomosis (Kulkarni and Bellamy, 2001; Guilherme et al., 2007; Troiano and Zarelli, 2007; Berent et al., 2007). In this case, we opted for unilateral ureteronephrectomy because the size of the mass made it impossible to obtain clean margins. Furthermore, ureteral resection and anastomosis can be a surgical challenge owing to the risks of urinary leakage and stenosis (Yap et al., 2017). In our case, surgical resection was the treatment of choice and adjuvant chemotherapy was not prescribed at the owner’s request. During the follow-up, distant metastases occurred, leading to respiratory distress and death. The survival time was 4 months. A case of canine ureteral leiomyosarcoma (Yap et al., 2017) was treated with ureteronephrectomy associated with adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin (only one dose), and a similar survival (5.5 months) was reported, indicating that chemotherapy did not increase survival in this case. However, the patient reported previously developed progressive disease and was included in a metronomic regimen with chlorambucil 4 mg/m², but was euthanized one month later owing to progression. Another report achieved an 8-month survival in a canine patient affected by ureteral sarcoma with surgical excision as monotherapy (Deschamps et al., 2007). In a human clinical study (Nakajima et al., 1994), patients with ureteral leiomyosarcoma who underwent surgical resection associated with radiotherapy achieved a median survival of 9 years. An IHC panel was also performed as a complementary examination to further characterize ureteral leiomyosarcoma. In contrast to previous reports (Deschamps et al., 2007), we observed positive staining for smooth muscle actin and desmin. This could demonstrate the heterogeneous pattern of sarcomas not presenting all the same markers. However, with only one report presenting IHC information, it is difficult to conclude such a direct correlation. The authors believe that the lower survival rate achieved may be related to intense intraoperative hemorrhage, which may have contributed to the spread of tumor cells and may have been owing to the tumor size (12 in), indicative of malignant behavior. Information in the veterinary literature regarding the efficacy of chemotherapy in the treatment of canine ureteral leiomyosarcomas is scarce. AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank Cynthia M. Bueno, DVM, and MSc, who performed the surgery and provided technical assistance. The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authors’ contributionsDCS, YAR, CEF, and DSA conceived and designed the project; CMB provided technical assistance foundational to this study; DCS, YAR, and DSA acquired the data; LGDB and CEF analyzed the immunohistochemistry data; LFM, LGDB, and CEF analyzed the histopathological data; DCS, YAR, LGDB, LFM, CEF, and DSA analyzed and interpreted the data; DCS, YAR, CEF, and DSA wrote the paper. FundingThe authors did not receive any grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Data availabilityAll data are provided in the manuscript. ReferencesBerent, A.C., Weisse, C. and Bagley, D. 2007. Ureteral stenting for benign and malignant disease in dogs and cats. Vet. Surg. 36, E1–E29. Berzon, J.L. 1979. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the ureter in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 175, 374–376. Burton, C.A., Day, M.J., Hoston-Moore, A. and Holt, P.E. 1994. Ureteric fibroepithelial polyps in two dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 35, 593–596. Chen, L.V., Chen, N., Zhu, X., Zhang, X. and Zhong, Z. 2008. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the ureter. Asian J. Surg. 31, 191–194. Crow, S.E. 1985. Urinary tract neoplasms in dogs and cats. Comp. Cont. Ed. Pract. Vet. 7, 607–618. Deschamps, J.Y., Roux, F.A., Fantinato, M. and Albaric, O. 2007. Ureteral sarcoma in a dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 48, 699–701. Font, A., Closa, J.M. and Mascort, J. 1993. Ureteral leiomyoma causing abnormal micturition in a dog. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 29, 25–27. Guilherme, S., Polton, G., Bray, J., Blunden, A. and Corzo, N. 2007. Ureteral spindle cell sarcoma in a dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 48, 702–704. Hanika, C. and Rebar, A.H. 1980. Ureteral transitional cell carcinoma in the dog. Vet. Pathol. 17, 643–646. Hattel, A.L., Diters, R.W. and Snavely, D.A. 1986. Ureteral fibropapilloma in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 188, 873. Inkelmann, M.A., Kommers, G.D., Fighera, R.A., Irigoyen, L.F., Barros, C.S.L., Silveira, I.P. and Trost, M.E. 2011. Neoplasmas do sistema urinário em 113 cães. Pesq.Vet. Bras. 31, 1102–1107. Johnston, S.A., Karen, M. and Tobias. 2018. Ureters. In: Textbook of Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, 115, pp: 5953–5967. Kulkarni, R. and Bellamy, E. 2001. Nickel-titanium shape memory alloy Memokath 051 ureteral stent for managing long-term ureteral obstruction: 4-year experience. J. Urol. 166, 1750–1754. Liska, W.E. and Patnaik, A.K. 1977. Leiomyoma of the ureter of a dog. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 13, 83–84. Meuten, D.J. 2002. Tumours of the urinary system. In Tumors of domestic animals. Eds., Meuten, D.J. 4th ed. Ames, IA: Lowa State University Press, pp: 524. Meuten, D.J. and Meuten, T.L.K. 2017. Tumours of the urinary system. In Tumors of domestic animals. Eds., Meuten, D.J. 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp: 680. Johnson, G.C., Miller, M.A. and Ramos-Vara, J.A. 1995. Comparison of argyrophilic nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs) and mitotic index in distinguishing benign from malignant canine smooth muscle tumors and in separating inflammatory hyperplasia from neoplastic lesions of the urinary bladder mucosa. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 7, 127–136. Nakajima, F., Terahata, S., Hatano, T. and Nishida, K. 1994. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the ureter. Urol. Intern. 53, 166–168. Polit, J.A., Moore, E.V. and Epperson, E. 2020. Primary ureteral hemangiosarcoma in a dog. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 1–6. Troiano, D. and Zarelli, M. 2017. Multimodality imaging of primary ureteral hemangiosarcoma with thoracic metastasis in an adult dog. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound, 60, E38–E41. Yap, F.W., Huizing, X.B., Rasotto, R. and Bowlt-Blacklock, K.L. 2017. Primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma in a dog. Aust. Vet. J. 95, 68–71. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Sousa DCD, Rossi YA, Benevenuto LGD, Fonseca-alves CE, Magalhães LF, Bueno CM, Anjos DSD. Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14(7): 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 Web Style Sousa DCD, Rossi YA, Benevenuto LGD, Fonseca-alves CE, Magalhães LF, Bueno CM, Anjos DSD. Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=147794 [Access: January 24, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Sousa DCD, Rossi YA, Benevenuto LGD, Fonseca-alves CE, Magalhães LF, Bueno CM, Anjos DSD. Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14(7): 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Sousa DCD, Rossi YA, Benevenuto LGD, Fonseca-alves CE, Magalhães LF, Bueno CM, Anjos DSD. Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. Open Vet. J.. (2024), [cited January 24, 2026]; 14(7): 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 Harvard Style Sousa, D. C. D., Rossi, . Y. A., Benevenuto, . L. G. D., Fonseca-alves, . C. E., Magalhães, . L. F., Bueno, . C. M. & Anjos, . D. S. D. (2024) Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. Open Vet. J., 14 (7), 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 Turabian Style Sousa, Danilo Cintra De, Ygor Amaral Rossi, Luíz Guilherme Dercore Benevenuto, Carlos Eduardo Fonseca-alves, Larissa Fernandes Magalhães, Cynthia M. Bueno, and Denner Santos Dos Anjos. 2024. Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. Open Veterinary Journal, 14 (7), 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 Chicago Style Sousa, Danilo Cintra De, Ygor Amaral Rossi, Luíz Guilherme Dercore Benevenuto, Carlos Eduardo Fonseca-alves, Larissa Fernandes Magalhães, Cynthia M. Bueno, and Denner Santos Dos Anjos. "Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy." Open Veterinary Journal 14 (2024), 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Sousa, Danilo Cintra De, Ygor Amaral Rossi, Luíz Guilherme Dercore Benevenuto, Carlos Eduardo Fonseca-alves, Larissa Fernandes Magalhães, Cynthia M. Bueno, and Denner Santos Dos Anjos. "Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy." Open Veterinary Journal 14.7 (2024), 1708-1715. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Sousa, D. C. D., Rossi, . Y. A., Benevenuto, . L. G. D., Fonseca-alves, . C. E., Magalhães, . L. F., Bueno, . C. M. & Anjos, . D. S. D. (2024) Canine primary ureteral leiomyosarcoma treated with unilateral left ureteronephrectomy. Open Veterinary Journal, 14 (7), 1708-1715. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i7.20 |