| Case Report | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14(11): 3120-3126 Open Veterinary Journal, (2024), Vol. 14(11): 3120-3126 Case Report Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphyPaloma Helena Sanches da Silva*, Renato Dornas de Oliveira Pereira, Anna Paula Botelho França, Nathalia Estevão Caixeta, Lívia Mariana Lopes Monteiro, Scarlath Ohana Penna dos Santos and Rodrigo dos Santos HortaDepartment of Veterinary Clinic and Surgery, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, Brazil *Corresponding Author: Paloma Helena Sanches da Silva. Department of Veterinary Clinic and Surgery, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Email: palomasanches.vet [at] gmail.com Submitted: 22/08/2024 Accepted: 21/10/2024 Published: 30/11/2024 © 2024 Open Veterinary Journal

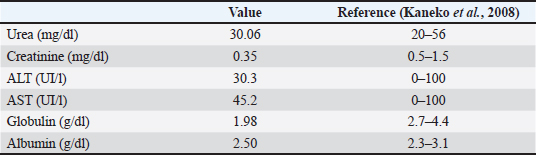

AbstractBackground: Surgeries performed on the gastrointestinal system represent a significant caseload among small animal surgeries. Colostomy aims to temporarily or permanently divert the gastrointestinal tract but it is not commonly performed in veterinary medicine. Information regarding such procedures is scarce and the surgical technique is poorly described. Thus, the main objective of this study is to report a modified temporary colostomy performed in a dog after the development of rectocutaneous fistulas in the perineum as a surgical complication of unilateral perineal herniorrhaphy. Case Description: An 8-year-old male Lhasa Apso dog was attended due to the appearance of rectocutaneous fistulas with fecal content draining, as a complication of a recent perineal herniorrhaphy. A modified temporary colostomy was created by positioning the intestinal segment parallel to the lateral abdominal wall as a rescue procedure to allow healing of the perineum for later definitive repair of the hernia. Conclusion: The modified temporary colostomy allowed healing of the perineum by temporarily diverting the flow of fecal material. Keywords: Canine, Complications, Intestinal bypass, Intestine surgery, Stoma. IntroductionThe large intestine corresponds to the final portion of the digestive tract, and in dogs, it is divided into the cecum, colon—ascending, transverse, descending—and rectum, with the colon representing the largest portion of this intestinal segment. Colostomy results on temporarily or permanent diversion of the gastrointestinal tract. With the purpose of managing colonic or rectal diseases and even reducing the complications of enteroanastomoses by diverting intestinal contents from the affected site until there is a resolution of the inflammatory process and adequate healing (Poskus et al., 2014; Carannante et al. 2019; Samy et al., 2020). As in human patients, colostomy results in the creation of a stoma in the colon connected to a collection bag acting as a continuous flow system (Gooszen et al., 2000) and, despite being considered a life-saving technique in most cases, there is still little information available about its implementation in dogs and cats, mainly due to the resistance of their owners or caregivers in managing a patient with a colostomy (Tsioli et al., 2009). This study aimed to report a modified temporary colostomy technique performed in a dog after the development of rectocutaneous fistulas in the perineum as a surgical complication of a recent unilateral perineal herniorrhaphy, as well as to address indications and general aspects of the main surgical colostomy techniques used in Veterinary Medicine. Case DetailsAn 8-year-old neutered male Lhasa Apso dog, weighing 7.9 kg, was attended at the Veterinary Hospital of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais due to complications following a recent perineal herniorrhaphy. Ninety-six hours post-surgery, the dog presented with pain, vocalization, and bleeding along with fecal content in the surgical wound. The patient had previously undergone an initial herniorrhaphy combined with orchiectomy 5 years earlier and had recovered well, but it faced an ipsilateral recurrence 7 months after the first procedure and since then had been managed with mineral oil, according to his guardian. The hernia was deemed reducible, and a new herniorrhaphy was performed with the polypropylene mesh fixed to the lateral coccygeal muscle, levator ani muscle, and ischial periosteum using 0 nylon sutures in a Sultan pattern. Upon clinical examination, a cutaneous fistula medial to the surgical wound was observed, draining fecal content, suggesting a rectocutaneous fistula as a complication of the recent surgery (Fig. 1). The patient had been discharged 48 hours post-surgery and was receiving orally meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg every 24 hours for 4 days), tramadol (5 mg/kg every 08 hours for 4 days), dipyrone (25 mg/kg every 24 hours for 3 days), and amoxicillin + clavulanate (22 mg/kg every 08 hours for 4 days). Surgical risk tests were performed, including a new blood count and renal and hepatic biochemical profile (Tables 1 and 2). The patient was re-evaluated and then referred for a ventral midline celiotomy for deferentopexy and colopexy, both performed with 3-0 nylon sutures, as well as a new surgical revision in the right perineum. During the perineal approach, near the fistulous tract between the right rectal wall and the perineal skin, adjacent to the surgical wound, it was observed fecal contamination of the polypropylene mesh used for pelvic diaphragm synthesis during the previous herniorrhaphy. During surgery, the synthetic mesh was removed along with the internal fistulous tracts and adherences. A sample of the contents drained by the rectocutaneous fistula and the contaminated mesh fragment were obtained and sent for culture and antibiogram. The area was thoroughly washed with sterile 0.9% NaCl solution, and the perineum was reconstructed by primary apposition but without reconstruction of the pelvic diaphragm. Forty-eight hours after this intervention, two new cutaneous fistulas appeared in the perineum. At this point, another reintervention was necessary, and a temporary colostomy was performed followed by another fistulectomy, extensive saline washing, Penrose drain placement, and skin synthesis, aiming to manage the infected perineal wound while feces were temporarily diverted to an ostomy created in the descending colon leading to the cutaneous flank region. A new intervention for definitive herniorrhaphy was postponed until the complete resolution of the infection. For the temporary colostomy technique, the patient was anesthetized and initially positioned in dorsal recumbency for antisepsis with 2% degerming chlorhexidine followed by 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine on the entire ventral abdomen and left lateral wall. A ventral midline celiotomy was performed through a retro-umbilical and parapreputial skin incision. The previous colopexy was reverted and the descending colon was exposed. Next, a longitudinal and rectilinear skin incision was made in the left lateral abdominal wall, in the flank, until the muscle layers of the abdominal wall were visualized, whose fibers were separated, and the parietal peritoneum was ruptured, opening another communication with the interior of the abdominal cavity (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, the antimesenteric border of the descending colon was exteriorized through the flank access, and a rectilinear incision was made only on the seromuscular layer of the colon, and the edges of this colonic layer were sutured internally to the muscle layers of the ipsilateral abdominal wall using a simple continuous suture with 4-0 poliglecaprone thread. Then, with the abdominal cavity isolated by compresses at the midline, a rectilinear incision was made on the submucosa and mucosa layers of the mentioned segment of the colon, now fixed to the abdominal wall, resulting in its opening and, therefore, exposing its lumen. Mucocutaneous sutures were placed around the created colonic ostomy in a simple interrupted pattern with a 4-0 poliglecaprone thread (Fig. 2B). The colonic ostomy appeared patent with feces present in the organ lumen and no fecal content spillage in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 2C). Surgical instruments and surgeons’ gloves were replaced, and the ventral midline celiotomy was conventionally closed. Subsequently, the right perineal region was accessed after antisepsis, removing all fistulous tracts from the rectum to the skin, including a small residual mesh fragment that adhered to the rectum. After copious washing with sterile saline solution, a Penrose drain was implanted and the cutaneous wound was sutured with 3-0 nylon thread in a simple interrupted pattern.

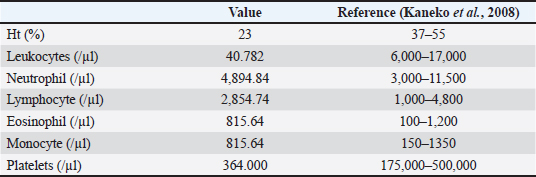

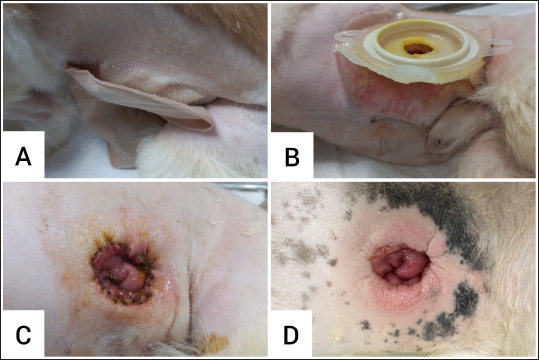

Fig. 1. Presence of rectocutaneous fistula in a dog draining fecal content in the right perineal region, medial to the perineal herniorrhaphy suture. Table 1. Hematological findings in a dog with dog with rectocutaneous fistula.

Table 2. Biochemical findings in a dog with dog with rectocutaneous fistula.

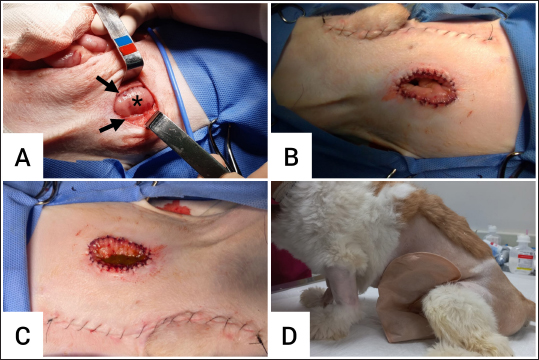

Postoperatively, a colostomy bag was attached to the ostomy to collect feces (Fig. 2D). The patient remained hospitalized, wearing an Elizabethan collar and with a prescription containing meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg every 24 hours for 4 days, intravenously), methadone (0.2 mg/kg every 06 hours for 2 days, intramuscular) and dipyrone (25 mg/kg every 08 hours for 4 days, intravenously), enrofloxacin (5 mg/k every 12 hours for 10 days), and Clindamycin (11 mg/kg every 08 hours for 7 days) intravenously. The surgical wound and Penrose drain were cleaned daily with saline solution and 0.12% aqueous chlorhexidine antiseptic, and subsequently occluded with a bandage. Despite the proper adaptation of the colostomy bag (Fig. 3A), premature removal and erythematous areas of peristomal dermatitis were observed (Fig. 3B and C). This dermatitis was treated topically with cleaning and diaper rash ointment after each defecation, maintaining a disposable diaper in place, and using an Elizabethan collar. With the reduction of secretions in the drain inserted in the perineum, it was removed, and the drain exit hole was allowed to heal by secondary intention. The culture and antibiogram results showed growth of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp, sensitive to enrofloxacin. The patient recovered well clinically, laboratory tests were satisfactory, the colonic ostomy and perineal surgical wound evolved well, and the patient was conditionally discharged with weekly follow-up visits for complete perineal healing and subsequent surgical reintervention for colostomy reversal and definitive perineal herniorrhaphy. However, 1 month after the temporary colostomy, despite the patent colostomy (Fig. 3D) and the perineum without new rectocutaneous fistulas, the owner refused to continue the definitive treatment, citing difficulties in managing the ostomy due to lack of time and financial constraints for surgical reintervention, resulting in the patient’s euthanasia. Post-mortem study was not allowed.

Fig. 2. A. Open body cavity and part of the antimesenteric border of the exposed descending colon (asterisk) after a rectilinear skin incision in the ipsilateral flank with consequent separation of muscle fibers (black arrows); B. Final aspect of the colostomy with mucocutaneous sutures after incision on the submucosa and mucosa layers of the descending colon, with prior fixation of the seromuscular layer of the organ to the abdominal wall; C. Patent colonic ostomy with feces present in the organ lumen in the immediate postoperative period; D. Colostomy bag attached to the created ostomy in the descending colon. DiscussionA colostomy is a technical term that involves creating an opening in the descending colon, connecting it to the external environment through the flank (Hardie and Gilson, 1997; Samy et al., 2020). The objective of the surgical technique is to divert the flow of the large intestine through the created stoma, which can be temporary or permanent depending on the circumstances (Tobias, 2011; Fossum, 2014; Williams, 2018; Smeak, 2020). The colostomy technique can be indicated palliatively in cases of unresectable intrapelvic masses causing obstruction in the region, such as primary or metastatic malignant neoplasms in the colon and rectum (Cinti and Pisani, 2019). Other indications include severe injuries in the intestinal segments, either traumatic or as an alternative route for fecal transit after surgical dehiscence in distal portions of the intestine (Tobias 1994; Cinti and Pisani, 2019). Additionally, it can provide favorable conditions for the healing of infected wounds in the perineum causing fistulas, whether acquired through perforation (Hardie and Gilson, 1997) or caused by congenital conditions like anal atresia (Tsioli et al., 2009). In the patient of this report, the colostomy was highly valuable for the definitive resolution of the rectocutaneous fistulas as the temporary diversion of the gastrointestinal content through the flank allowing resolution of the perineal infection, resolution of the inflammatory process, and complete healing (Tsioli et al., 2009). Complications after perineal hernia repair in dogs are not uncommon and may result in recurrence. One technique that can be used concomitantly with perineal hernia repair is deferentopexy. This technique is a surgical strategy that may offer benefits to the surgical treatment of perineal hernia in dogs, both in terms of protecting the organs involved in the hernia and in the efficiency of the treatment, preventing recurrence. The technique consists of fixing each of the vas deferens to the internal abdominal wall, creating a seromuscular tunnel from a double incision in the parietal peritoneum and transverse muscle, on each side of the internal abdominal wall. The vas deferens are then passed through this tunnel and sutured as a way to decrease pressure on the pelvic diaphragm and prevent possible recurrent caudal displacements of the bladder and prostate, thus serving as a complement to the surgical treatment of perineal hernia (Bilbrey et al., 1990). Other complications after perineal herniorrhaphy in dogs may include fecal incontinence and surgical wound infection (Sjollema and Van Sluijs, 1989). In a study of 100 dogs undergoing perineal herniorrhaphy, 7% of the operated animals developed perineal fistula, which was associated with the presence of nylon surgical sutures as a persistent niche for infection (Sjollema and Van Sluijs, 1989). In the patient of this report, polypropylene mesh was used for the reconstruction of the pelvic diaphragm and fixed with nylon sutures. Both the mesh and the nylon sutures are non-absorbable synthetic materials frequently used in herniorrhaphies without complications, as long as these materials are not contaminated during the surgical procedure (Falagas and Kasiakou, 2005). In the reported patient, the formation of rectocutaneous fistulas following perineal herniorrhaphy might have been caused by bacterial contamination of the polypropylene mesh fixed with nylon sutures, which likely passed through the rectal wall instead of being limited to the atrophied external anal sphincter muscle during the herniorrhaphy (Saha et al., 2022). A similar situation has been reported in a 50-year-old man following abdominal herniorrhaphy, resulting in enterocutaneous fistula. The Polypropylene mesh was sutured for abdominal wall reconstruction but accidentally passed through the intestine with subsequent contamination of the implant. In the patient of this report, the non-absorbable surgical suture might have come into contact with the rectal lumen, resulting in contamination extending to the polypropylene mesh, leading to bacterial biofilm formation and the establishment of a severe inflammatory-infectious process, culminating in fistulation. According to Hardie and Gilson (1997), perforations in the distal rectum contribute to the genesis of rectocutaneous fistulas. Moreover, it is known that contamination of synthetic mesh or other implanted synthetic materials in organic tissues leads to the occurrence of fistulous tracts as the body’s attempt to eliminate the infection (Saha et al., 2022).

Fig. 3. A. Colostomy bag initially attached to the colonic ostomy in the left flank of the dog; B. Peristomal dermatitis in the postoperative period; C. Ostomy without colostomy bag attachment; D. Well-healed colonic ostomy 1 month post-surgery. Depending on the circumstances and objectives for use, two types of colostomy techniques have been described in dogs and cats to divert the terminal portion of the intestine. These techniques include loop colostomy and end colostomy (Hardie and Goldi, 1997; Tobias, 2011; Fossum, 2014; Smeak, 2020). According to Hardie and Goldi (1997), creating a stoma can be performed through a ventral abdominal approach or through the flank region, with or without stoma support rods. Fossum (2014) and Smeak (2020) describe both techniques through the flank approach. Loop colostomy is frequently used as a temporary technique and involves exteriorizing a part of the colon that assumes a loop shape to be sutured to the lateral abdominal wall, with the use of a support rod and recommended while the stoma heals (Averbach and Ribeiro, 2007). The approach is performed on the left flank due to the location of the descending colon (Fossum 2014). A four-centimeter circular incision is made in the skin of the ipsilateral flank, extending down to the subcutaneous layer. The muscle fibers of the abdominal wall are separated to access the abdominal cavity, providing access to the descending colon and its passage through the surgical opening without compromising the organ’s blood flow (Fossum, 2014; Smeak, 2020). The descending colon is then isolated and exteriorized through the previously created incision in the flank. In a loop form, the colon is sectioned, exposing its mucosa. Subsequently, its seromuscular edges are sutured to the skin, causing the intestinal mucosa to evert over the skin edges (Smeak, 2020). End colostomy can also be employed temporarily and later reversed (Tsioli et al., 2009; Smeak, 2020). For this approach, the patient is positioned in dorsal recumbency for the transection of the descending colon, resulting in two divided ends. The aboral segment of the colon can be preserved through a Parker-Kerr suture or stapling if the goal is to reverse the stoma or it can be removed if the procedure is palliative or due to irreversible lesions. The oral segment can also be temporarily closed until it is exteriorized perpendicularly through the left flank incision. Once exteriorized, the previously occluded portion is excised to avoid breaking aseptic surgery, and then its entire circumference is sutured to the flank, starting with the seromuscular layer of the exteriorized colon together with the muscular edges of the flank in a simple interrupted pattern. Subsequently, the mucosal and submucosal layers are sutured to the flank skin in a simple interrupted pattern. For reversal, the stoma is undone, the flank region sutured, the intestinal ends excised, and intestinal continuity restored through end-to-end enteroanastomosis (Tsioli et al, 2009; Williams, 2018). Based on the described colostomy techniques, in the patient of this report, the colostomy was performed through a ventral median celiotomy for exposure of the descending colon, resembling the loop colostomy technique as it uses the antimesenteric border of the descending colon to be exteriorized through the flank. However, it differs from this technique by not assuming a loop disposition, eliminating the need for a temporary rod, and thus establishing communication with the external environment through the flank by positioning the intestinal segment parallel to the lateral abdominal wall. To avoid the risk of peritonitis, a suture is first initiated between the seromuscular layer of the antimesenteric border of the descending colon and the muscular layer of the flank, and only then an incision is made in the intestinal mucosa and submucosa, allowing access to its lumen. Therefore, the mucosa and submucosa of the colon are sutured to the flank skin, resulting in a mucocutaneous suture for stoma creation. The postoperative period of colostomy in dogs can be long and challenging, as it is still a rarely reported procedure in the surgical routine of small animals, either due to potential complications that may occur at the stoma or peristomal level or due to the meticulous and laborious management required (Hardie and Gilson, 1997; Fossum, 2014; Williams, 2018; Cinti and Pisani, 2019; Smeak, 2020; Higashimoto, 2023). Peristomal dermatitis, fecal incontinence, stoma dehiscence, and infection, as well as peritonitis, are the main complications cited after colostomy (Hardie and Gilson, 1997; Tsioli et al, 2009; Cinti and Pisani, 2019). In the patient of this report, there was no peritonitis, nor stoma infection and dehiscence in the postoperative period, which can be attributed to aseptic care during the technique, delicate tissue manipulation, preservation of blood supply, minimal trauma promotion, proper tissue apposition, and tension-free synthesis. Failure to implement these conditions results in poor tissue perfusion and healing, as well as dehiscence risks due to the high bacterial load in the organ’s microbiota, biomechanical stress in the region, and lower blood circulation compared to other parts of the gastrointestinal tract (Fossum, 2014). Other complications such as stoma retraction and intestinal prolapse may occur (Samy et al., 2020) but were not presented in the reported case. However, peristomal dermatitis and fecal incontinence were observed postoperatively. According to Samy et al. (2020), dermatitis is common and it is usually observed regardless of the technique performed, and may be associated with direct contact of the peristomal skin with the intestinal mucosa and the fact that the flange that fixes the colostomy bag, when positioned, causes skin irritation around the stoma. The bag adhesive, which was created to adhere to human skin, does not adhere well to the dog skin and contributes to dermatitis (Samy et al., 2020). Furthermore, fecal incontinence is inevitable due to the fact that there is no sphincter to control the exit of feces. Therefore, colostomy requires commitment and home management with constant hygiene, which can lead to greater resistance on the part of the tutor in accepting the use of the technique, as demonstrated in the outcome of this report (Hardie and Gilson, 1997). Unfortunately, it was not possible to definitively repair the perineal hernia even after the resolution of the rectocutaneous fistulas promoted by the temporary colostomy, as the owner claimed difficulties in managing the fecal incontinence and bearing the costs for a new surgical procedure. ConclusionAlthough definitive perineal herniorrhaphy was not authorized by the owner, the temporary colostomy allowed for favorable healing of the perineum by temporarily diverting fecal flow. Clear communication about potential complications, management difficulties, and related costs can encourage greater adherence to colostomy techniques given the mentioned indications, with the possibility of reversal and re-establishment of the patient’s physiology, health, and well-being. AcknowledgmentsNone. Conflict of interestThe author declares that there is no conflict of interest. FundingThis research received no specific grant. Authors’ contributionsSILVA, PHS wrote the manuscript with contributions from FRANÇA, APB; CAIXETA, NF; MONTEIRO, LML; SANTOS, SOP, and HORTA, RS. PEREIRA, RDO, and SILVA, PHS managed the case before and after the referral. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and agreed to its submission. Data availabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript. ReferencesAverbach, M. and Ribeiro, P.C. 2007. Apendicectomias, colostomias e colectomias. In Técnica cirúrgica: bases anatômicas, fisiopatológicas e técnicas da cirurgia, 4th ed. Ed., Goffi, F.S. São Paulo, Brazil: Atheneu, pp: 613–625. Bilbrey, S., Smeak, D. and Dehoff, W. 1990. Fixation of the deferent ducts for retrodisplacement of the urinary bladder and prostate in canine perineal hernia. Vet. Surg. 19(1), 24–27. Carannante, F., Mascianna, G. and Lauricella, S. 2019. Skin bridge loop stoma: outcome in 45 patients in comparison with stoma made on a plastic rod. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 34, 2195–2197. Cinti, F. and Pisani, G. 2019. Temporary end-on colostomy as a treatment for anastomotic dehiscence after a transanal rectal pull-through procedure in a dog. Vet Surg. 48(5), 897–901. Falagas, M.E. and Kasiakou, S.K. 2005. Mesh-related infections after hernia repair surgery. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11(1), 3–8. Fossum, T. 2014. Colostomia. In Cirurgia de pequenos animais, 4th ed. Ed., Fossum, T. vol 20, Elsevier, Rio de Janeiro, pp: 540–541. Gooszen, A.W., Geelkerken, R.H. and Hermans, J. 2000. Quality of life with a temporary stoma: ileostomy vs. colostomy. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 43, 650–655. Hardie, E.M. and Gilson, S.D. 1997. Use of colostomy to manage rectal disease in dogs. Vet. Surg. 26(4), 270–4. Higashimoto, I. 2023. Temporary loop ileostomy versus transverse colostomy for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a retrospective study. Surg. Today. 53, 621–627. Kaneko, J.J., Harvey, J.W. and Bruss, M. 2008. Clinical biochemistry of domestic animals. 6th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Inc.; Cambridge, UK: Academic Press, pp: 117–138. Poskus, E., Kildusis, E. and Smolskas, E. 2014. Complications after loop ileostomy closure: a retrospective analysis of 132 patients. Viszeralmedizin 30, 276–280. Saha, T., Wang, X., Padhye, R. and Houshyar, S. 2022. A review of recent developments of polypropylene surgical mesh for hernia repair. Open Nano. 7, 100046. Samy, A., Abdalla, A. and Rizk, A. 2020. Evaluation of short-term loop colostomy in dogs using conventional and supporting subcutaneous silicone drain techniques. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 7(4), 685–691. Sjollema, B.E. and Van Sluijs, F.J. 1989. Perineal hernia repair in the dog by transposition of the internal obturator muscle. Vet. Quart. 11(1), 18–23. Smeak, D.D. 2020. Colostomy and jejunostomy. In Gastrointestinal surgical techniques in small animals, 1. ed. Eds., Smeak, D.D. and Monnet, E. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, vol 30, pp: 225–229. Tobias, K.M. 1994. Rectal perforation, rectocutaneous fistula formation, and enterocutaneous fistula formation after pelvic trauma in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 205, 1292–1296. Tobias, K.M. 2011. Veterinary surgery: small animal, 1st ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Editora Elsevier. Tsioli, V., Papazoglou, L.G., Anagnostou, T., Kouti, V. and Papadopoulou, P. 2009. Use of a temporary incontinent end-on colostomy in a cat for the management of rectocutaneous fistulas associated with atresia ani. J. Feline Med. Surg. 11(12), 1011–1014. Williams, J.M. 2018. Colon. In Veterinary surgery: small animal, 1. ed. Eds., Tobias, K.M. and Johnston, S.A. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; pp: 1542–1563. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Silva PHSD, Pereira RDDO, Franca APB, Caixeta NE, Monteiro LML, Santos SOPD, Horta RDS. Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14(11): 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 Web Style Silva PHSD, Pereira RDDO, Franca APB, Caixeta NE, Monteiro LML, Santos SOPD, Horta RDS. Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=216639 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Silva PHSD, Pereira RDDO, Franca APB, Caixeta NE, Monteiro LML, Santos SOPD, Horta RDS. Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14(11): 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Silva PHSD, Pereira RDDO, Franca APB, Caixeta NE, Monteiro LML, Santos SOPD, Horta RDS. Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. Open Vet. J.. (2024), [cited January 25, 2026]; 14(11): 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 Harvard Style Silva, P. H. S. D., Pereira, . R. D. D. O., Franca, . A. P. B., Caixeta, . N. E., Monteiro, . L. M. L., Santos, . S. O. P. D. & Horta, . R. D. S. (2024) Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. Open Vet. J., 14 (11), 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 Turabian Style Silva, Paloma Helena Sanches Da, Renato Dornas De Oliveira Pereira, Anna Paula Botelho Franca, Nathalia Estevão Caixeta, Lívia Mariana Lopes Monteiro, Scarlath Ohana Penna Dos Santos, and Rodrigo Dos Santos Horta. 2024. Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. Open Veterinary Journal, 14 (11), 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 Chicago Style Silva, Paloma Helena Sanches Da, Renato Dornas De Oliveira Pereira, Anna Paula Botelho Franca, Nathalia Estevão Caixeta, Lívia Mariana Lopes Monteiro, Scarlath Ohana Penna Dos Santos, and Rodrigo Dos Santos Horta. "Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy." Open Veterinary Journal 14 (2024), 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Silva, Paloma Helena Sanches Da, Renato Dornas De Oliveira Pereira, Anna Paula Botelho Franca, Nathalia Estevão Caixeta, Lívia Mariana Lopes Monteiro, Scarlath Ohana Penna Dos Santos, and Rodrigo Dos Santos Horta. "Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy." Open Veterinary Journal 14.11 (2024), 3120-3126. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Silva, P. H. S. D., Pereira, . R. D. D. O., Franca, . A. P. B., Caixeta, . N. E., Monteiro, . L. M. L., Santos, . S. O. P. D. & Horta, . R. D. S. (2024) Modified temporary colostomy in a dog for treatment of rectal infection after complication of perineal herniorrhaphy. Open Veterinary Journal, 14 (11), 3120-3126. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i11.42 |