| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(3): 1480-1487 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(3): 1480-1487 Research Article Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horsesMohamed Shokry1*, Lutfi Ben Ali2 and Mohamed El-Sharkawy31Surgery, Anesthesiology and Radiology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt 2Department of Surgery and Theriogenology, University of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya 3Equine Hospital, Police Academy, Cairo, Egypt *Corresponding Author: Mohamed Shokry. Surgery, Anesthesiology and Radiology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. Email: mshokry [at] cu.edu.eg Submitted: 04/12/2024 Accepted: 05/02/2025 Published: 31/03/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

AbstractBackground: Showjumping athletic horses are frequently affected by back pain, which in turn influences their performance and equestrian activities. Aim: The aim of the present study was to determine the etiological factors predisposing to back problems in show jumping horses and how to diagnose, and manage them. Methods: A total of 75 cases (45 geldings and 30 mares, aged between 8 and 23 years and weighing 420–550 Kg) with histories suggestive of back problems and low competitive ability as show jumping were used in this study. The evaluation of data was based on the inputs of case history, clinical signs, clinical examination, local analgesic injection, and diagnostic imaging. Results: The demonstrated types of back disorders were back deformities (lordosis, scoliosis, and sacral hunter bump) (5 cases–6.66%), muscular strain (18 cases–24%), sacroiliac sprain (30 cases–40%), vertebral lesions, mostly crowding and spondylosis (16 cases–21.33%), and skin lesions due to tack or rider-induced back pain (saddle mark, lumps or scars) (6 cases–8%). Treatment included rest, anti-inflammatory drugs, and intra-articular injection of local corticosteroids. Conclusion: Conventional clinical examination visually, at rest, exercise, and spinal reflexes is indispensable for the diagnosis of back disorders. Complementary diagnosis via diagnostic imaging and local analgesic injection is necessary to determine the location of pain. Keywords: Back disorder, Show jumping horses, Diagnosis, Management. IntroductionBack problems have been documented as an important cause of performance problems in athletic horses (Jeffcott, 1980; Turner 2011; Mayaki et al., 2019). Back pain can arise from a variety of conditions revolving around soft tissue desmopathy lesions of the supraspinous and interspinous ligament and strain of the longissimus muscle (Greve and Dyson, 2014; Findley and Singer, 2015). Osseous injuries include impinging dorsal spinous processes (IDSP, kissing spines), osteoarthritis of articular processes, intervertebral disc disease, mal-conformations, and vertebral fractures (Jeffcott, 1980; Wong et al., 2006; Girodroux et al., 2009; Zimmerman et al., 2012), tack-associated problems (poor saddle fit), and excessive rider weight (Dyson et al., 2015). Clinical signs are often nonspecific and may include poor performance, refusal at jumps, reduced hindlimb impulsion, poor croup muscling, back soreness, reluctance to trot or pace at high speeds, or low grade and shifting hindlimb lameness (Cauvin, 1997; Jeffcott, 1980; Landman et al., 2004). The diagnosis of back pain in horses depends on the clinical examination and diagnostic imaging, including ultrasound, radiography, and thermography (Jeffcott, 1993; Denoix, 1999; Fonseca et al., 2006; Henson et al., 2007; Kent Allen et al., 2010; Soroko and Howell, 2018). Modern diagnostic modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) and nuclear scintigraphy, are promising for diagnosis but are not easily available to practitioners (Burns et al., 2018). Treatment is focused primarily on relieving pain using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, corticosteroids, and local analgesics (Shokry, 2016; DeMelo and Ferreira, 2021). Surgical resection of the impinged parts of the spinous process in affected horses is used (Walmsley et al., 2010). Chiropractic and physiotherapy may be directly applied to back problems for rehabilitation and stimulation of neurological reflexes using thermal modalities, massage, acupuncture, and shock waves (Martin and Klide, 1987; Ridgway and Harman, 1999). With the increase in interest in equestrian sports in recent decades, attention has become devoted to the health status of athletic horses, which has become a real challenge that must accompany the prosperity of this sport. Back problems are one of the main problems that influence patient performance; therefore, they require a comprehensive study in addition to choosing a systematic diagnostic protocol according to limited capabilities and a reliable treatment option. Materials and MethodsThis study was conducted on 75 track and field horses with histories suggestive of back problems. All horses were from the Police Academy in Cairo. The horses were sorted as Hunter-jumper (25), Holsteiner (21), Thoroughbred (19), and Hanoverian (13). The breed encompassed 48 geldings and 30 mares, aged between 8 and 23 years, and weighed (420–550 Kg). Clinical examinationHistory A standard examination chart was designed for each presented case. Signalments of the horse, including age, sex, breed, sport type, and complaint, were recorded. Questions concerning information about the onset, duration, experience of the rider, condition of the tack and shoes, type of bridle, and temperament. A. Examination at rest1. Visual The affected horse was examined while standing on an even ground to assess: back mal-conformation (lordosis, kyphosis, or scoliosis), muscular atrophy (back, quarter, or thigh), and skin lesions (lumps, scars, or saddle marks). Palpation by digital pressure and pinching of the horse’s midline of the back to assess any hot spots, dipping, humping, tenderness, resentment, discomfort, or cringing was performed (Fig. 1 A–D).

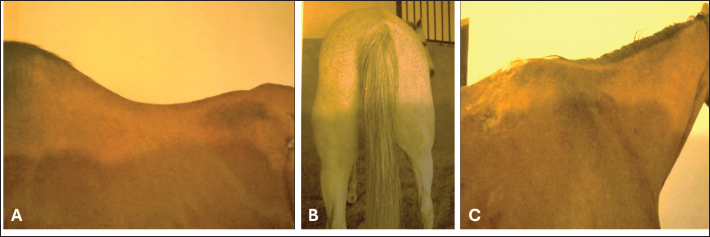

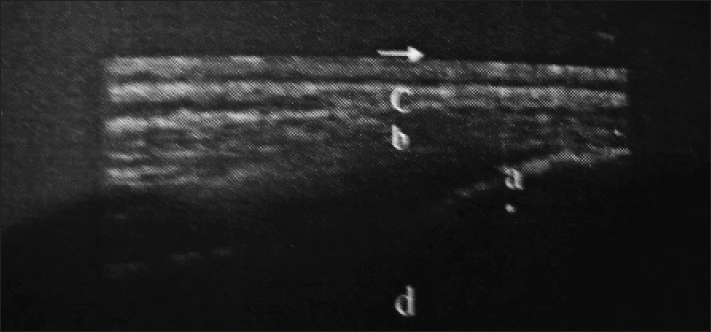

Fig. 1. A -(Lordosis), B- (Muscular atrophy) and C- (Saddle mark). 2. Rectal examination Rectal examination was performed to assess the ventral aspect of the caudal lumbar and sacrum for the presence of any painful swelling (intervertebral discs), evidence of iliac thrombosis, psoas and iliac myositis, prepubic tendon, inguinal rings, pelvic fracture, or sacroiliitis. B. Examination during exercise1. In hand On a loose rein, the presented horse was walked and trotted to assess gait abnormalities or claudication (poor hock flexion, dragging the toes, straddling of hind limbs, stiffness, or ataxia, and incoordination). Frequent turning of the horse in both directions was also performed to assess the flexibility of the spines. The back-and-down of the horse was also attempted to evaluate the sacroiliac joint. The Spavin test was performed to exclude hock or stifle problems. 2. Lunging Lunging exercise of the horse for 10 minutes in a sandy lunge yard was performed to evaluate the horse’s strides and the effect on gait when the horse warmed up. 3. Ridden and jumping The presented horse was saddled up to note any pain or discomfiture during girthing or mounting (cold back). The horse was then ridden by the usual rider to assess the horse’s responding at walk, trot, and canter. The horse was then tried to jump on a combination of 1 m fences with 10 m in between distances to evaluate the horse’s action with exaggerated exercise (i.e., rush against the fences or showing reluctance and resentment). Many other important sign criteria were also recorded, which depended on the rider’s experience and included: refusal to stand during mounting, sinking when the rider mounts, resenting the girth tightening, jumping mistakes or refusal, difficulty in ascending hills, bucking during upward transition from trot to canter/lope, stiffness and abnormal movement of the back, changing of jumping style, vigorous tail movement, teeth grinding, dragging one or more of the hind feet and reluctance to backing. C. Special tests for back pain assessment (Licka and Peham,1998)1. The active lateral bending range of motion of the neck and trunk (ALBRM). The assistant’s hand holding the green fodder bundle was directed toward the horse’s elbow and then placed against the lateral girth (Fig. 2A). The motion expressed by the horse’s head and neck toward the food bundle was recorded to assess mid-to-lowering neck flexion in lateral bending and rotation. Any marked limitation of motion or stiffness was recorded as unsound. 2. The active flexion range of motion of the mid-to-lower neck and withers (AFRM). The assistant’s hand holding the food bundle was directed cranially between the forelimbs and toward the front feet to assess the active flexion range of motion of the mid-to-lower neck and withers (Fig. 2B). Any marked limitation of motion or stiffness was recorded as unsound. 3. Spinal reflex test This test was performed by stroking any blunt object alongside the vertebral column from the withers to the base of the tail to test the dorsoflexion and ventroflexion of the back. Any reluctance or exaggerated response was recorded as unsound. D. Diagnostic imaging1. Radiographic examination A portable radiography device with limited imaging capacity (Kv100 & mA 30) was used. Lateral views of the dorsal apexes of the T2–T3 spinous processes on large-size films 35X43 cm were visualized in the standing position in certain cases only. 2. Ultrasonography examination Supraspinous and sacroiliac ligament ultrasonography in transverse and longitudinal planes were performed using a portable ultrasound machine and a 7.5-MHz linear array transducer. A stand-off water-bag cushion was used to improve the resolution of superficial structures. Three sound horses were also scanned US at the same locations for comparison (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. (A): Active lateral back range of motion. (B): Active flexion range of motion.

Fig. 3. Longitudinal ultrasongraphy at the sacro-iliac region (a-the dorsal sacroiliac ligament, b-longissimus dorsi tendon, c-gluteal fascia, and d- sacral tuber).

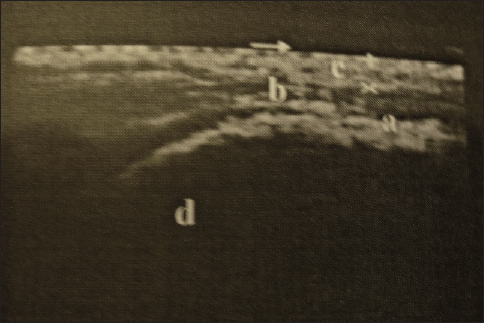

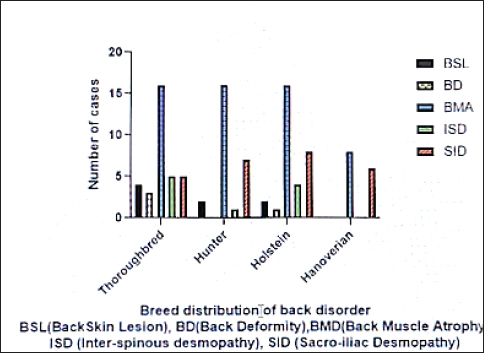

Fig. 4. Bony components of the sacropelvis illustrating sacroiliac needle position. E. Diagnostic injection1. Interspinous injection A local analgesic injection of 5 ml of MepivacaineR, 2% (Alexandria, Egypt) was performed in the interspinal space between the painful spinous process. The results were assessed after 15 minutes. 2. Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) injection For accurate accessibility of SIJ, 3 transverse sections at the sacral region of the back (as anatomical cadavers specimens intended for dissection) and an osseous construction pf sacro-pelvic specimen were used to test the feasibility of injection in a predetermined anatomical location (Fig. 4). Forty horses with suggestive SIJ complaints were used to evaluate the potential of diagnostic SIJ analgesia based on previous anatomical studies. Following restraining the horse in stanchion local aseptic preparation of the sacral region, A 13 cm, a 21-gauge needle was inserted axially to the cranial aspect of the ipsilateral sacral tuber according to the rider’s complaint side of the horse (left or right). The needle was directed obliquely and caudally at 30º to the vertical of the same side toward the SIJ. The needle was then advanced until contact was made with the bony floor formed by the sacral spine and medial iliac wall of the SIJ. Twenty milliliters of MepivacaineR, 2% were perfused in the vicinity while the needle was partially withdrawn to walk the horse for 15 minutes after injection before being assessed and ridden. ManagementThe following management and treatment protocols were adopted in the present cases of affected horses: Rest periods from 1 to 3 months, according to severity, in a loose box or stall, combined with reduced feed quantity were established in all affected cases. NSAID IV PhenylbutazoneR 4.4 mg/Kg/ day b.i.d for 5 days or descending oral administration 4 mg/day for 4 days, 3 mg/day for 4 days, 2 mg/day for 4 days, and 1 gm/day for 8 days were used to reduce pain. Patients with positive interspinous and SIJ injection analgesia were injected with therapeutic intra-articular tamacinolone acetonide, 40 mg (KenacortR Squib, SmithKline Beecham, Egypt) combined with 20 ml Mepivacaine local analgesic (2%). Statistical analysisThe recorded data were analyzed using Prism (GraphPad Software, Boston MA02110, USA). Relationship between the breed of the horses and the confidence interval frequency of the type of back injury. Ethical approvalEthical approval was not obtained because the study was considered routine hospital work. ResultsExamination of the remaining horses demonstrated scoliosis, hunter bump, quarter muscular asymmetry, and sacral or coxal tuber asymmetry in 2, 1, 19, and 30 horses, respectively. Back skin lesions as saddle marks, lumps, or scars were seen in 9 horses. Palpation by running the hands with pressure over the back for detection of tenderness, reluctance, or discomfiture showed great significance for locating the seat of trouble in approximately 50% of the presented cases. Rectal examination demonstrated (8 cases–8%) pelvic bony callus, iliac shaft asymmetry, and lumbar spondylosis. At exercise, hand walking showed the hind limb restricted movement, plaiting, and imbalanced walking with restricted vertebral or pelvic mobility (raised head and arched back) in the majority of the patients. Lunging for 15 minutes showed stiffness and poor hind limb impulsion in 15 cases (20%). Marked imbalance and coordination with tail swishing were noted when action was changed from trot to canter in 44 cases (58.66%). When ridden, the backs of 32 horses were sunken during mounting or girth tightening. Short turning was accompanied by a raised head and arched back in 20 cases. Jumping mistakes or refusals, particularly many fences, or fences over 3 feet with marked changes of the jumping stile, reluctant sliding stops, or backing were noted. The results of the regional motion test by active lateral flexion—bending range of motion for the neck and trunk, assisted range of motion test showed variable reactions and reached and spinal reflexes for the saddle and croup regions were found important for conventional assessment of back disorders as 45 cases (60%) showed an inability to elevate the trunk. Fifty three cases (70.6%) exhibited hind limb lameness manifested as restriction of movement combined with poor hock joint flexion and a tendency to drag the toe of one or both hindlimbs. Diagnostic imaging by radiographic examination was limited to identifying overriding thoracic dorsal vertebral spinous processes using an output of 20 mA at 90 kV within 0.1 second. However, most projections suffer from superimposition of the lungs and poor resolution. Ultrasonographic examination of the thoracolumbar dorsal spines and sacroiliac region revealed 30 cases with sacroiliac pain or injuries with heterogenic echogenicity and thickening of the dorsal sacroiliac ligament, 16 cases with dorsal spinous desmopathy, and 8 cases with echogenic changes of longissimus dorsi aponeurosis (Fig. 5). As the used horses were of different breeds, a comparison was made in the rate of back injuries among them to determine the breed most affected and the most common injuries as well. The following graph illustrates the generated descriptive individual clinical recorded data among different breeds of presented horses (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Longitudinal ultrasonography of the sacroiliac region showing sacroiliac desmopathy (a-sacroiliac enthesophytosis, b-longissimus dorsi tendon, c-gluteal fascia, and d-sacral tuber).

Fig. 6. The descriptive clinical recorded data among the different breeds of the presented horses. Diagnostic interspinous and sacroiliac analgesic injections were confirmatory in 40 patients with sacroiliac pain since marked improvements in gait and performance were observed. Treatment consisted of sufficient stall rest with mild walking for all patients (range: 1–3 months). Six cases of saddle lesions were managed with intensive skin care, perfect padding, and fitting of saddles. Intravenous NSAIDs to control pain at a dose rate of 4.4 mg/Kg b.i.d. for 5 days in mild cases (11 cases) and for 30 days in chronic cases (7 cases). DiscussionThe present study has achieved its aims by increasing the knowledge of back pain in athletic horses and allowing equine practitioners with limited equipment opportunities to manage such problems. It has been suggested that Back disorder is a major cause of poor performance in athletic horses (Jeffcott, 1980; Landman et al., 2004; Dyson, 2016; Mayaki et al., 2019). The condition is mostly attributed to some essential predisposing reasons, which include faulty tacking, poor training, rider overweight, unequal distribution of the rider’s weight, improper shoeing, low-quality feeding, and poor management. In the present study, the conventional diagnosis of back pain in horses, including anamnesis, clinical examination at rest and exercise, special back pain assessment tests, diagnostic imaging, and local analgesic injection, is indispensable and reliable in equine veterinary clinics. Analogous protocols have also been used (Jeffcott, 1993; Landman et.al., 2004; Kent Allen et al., 2010; Findley and Singer, 2015). Modern diagnostic modalities such as nuclear scintigraphy or CT, thermography, and electromyography are promising for the diagnosis of difficult cases; however, they are available in well-equipped equine clinics (Peham et al., 2001; Zimmerman et al., 2012; Burns et al., 2018). From the history, the etiology revolved around incorrect saddle, rider, or training, back mal-conformation, muscular strain, osteopathy of the spinous processes, and desmopathy of the interspinous or sacroiliac ligament. Several studies have reported similar reasons (Turner, 2011; Greve and Dyson, 2014; Clayton and Stubbs, 2016; Mayaki et al., 2019). Clinically, musculoskeletal dysfunction using the lateral bending and flexion range of motion ALBRM, AFRM and spinal reflex tests were assessed successfully and proved efficient for grading the lateral and dorsal vertebral flexions. Similar results have been reported in other studies (Martin and Klide, 1987). A system for motion analysis (expert vision system) was used in other studies (Licka and Peham, 1998) after placing markers and cameras to assess the spinal movement in maximum arching, dipping, and left and right flexion by measurements. The majority of the patients (70.6%) exhibited signs of hind limb lameness. A high prevalence of lameness has been reported in other studies (Cauvin, 1997; Landman et al., 2004). In the present study, ultrasonography of the interspinous and sacroiliac ligament was helpful in the diagnosis of 30 cases (40%) being diagnosed with sacro-iliac desmopathy. Furthermore, intraspinous or sacroiliac, local analgesic injections were considered effective diagnostic tools. Here, it is important to pay considerable attention to this joint during the examination as it may be the origin of the problem. These results are consistent with those of other studies (Engeli and Haussler, 2011; Dyson and Murray, 2003). Conservative treatments using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents combined with rest, correction of the saddle, compression, and massage therapy were used with non-eventful recovery. Peri-articular injection of corticosteroids with local anesthetic gave satisfactory results in positive cases of sacro-iliac desmopathy. Similar treatment protocols have been reported (Turner, 2011). Sacro-iliac desmopathy was highly prevalent among the presented cases while interspinous desmopathy came next. In this respect, racehorses and showjumpers are more prone to enthesophytosis of the spinous processes desmopathy of the interspinous ligament (Clayton and Stubbs, 2016). Thoroughbred jumper horses showed a high frequency of back disorders of all types, followed by Holsteiner and hunter-jumpers, while the Hanoverian showed the least frequency. Back muscle atrophy is a common sign in all breeds. ConclusionAdopting an inclusive protocol of examination, depending on conventional diagnosis including subjective assessment of case history, physical examinations at rest and motion, especially musculoskeletal and spinal reflex assessment tests, and supported by ultrasonography and local analgesic injection, has proven its efficiency for diagnosis of back pain in show jumping horses. Sacroiliac desmopathy cases accounted for a great deal in comparison with other disorders in which sacroiliacc injection of anti-inflammatory and local anesthetic was successfully treated. Poor saddle fit and schooling programs were the main predisposing factors. Adequate rest and early treatment were prerequisites for recovery. AcknowledgmentsNone. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. FundingThis research received no external funding. Authors’ contributionsAll authors equally contributed to this research. Data availabilityAll data were provided in the manuscript. ReferencesBurns, G., Dart, A. and Jaffcott, L. 2018. Clinical progress in the diagnosis of thoracolumbar problems in horses. Equine Vet. Educ. 30, 477–485. Cauvin, E. 1997. Assessment of back-pain in horses. Practice 19, 522–533. Clayton, H.M. and Stubbs, N.C. 2016. Enthesophytosis and impingement of the dorsal spinous processes in the equine thoracolumbar spine. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 47, 9–15. DeMelo, U.P. and Ferreira, C. 2021. Multimodal therapy for treatment of equine back pain: a report of 15 cases. Braz. J. Vet. Med. 43, e003321. Denoix, J.M. 1999.Ultrasonographic evaluation of back lesions. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 15, 131–159. Dyson, S. 2016. Evaluation of poor performance in competition horses: a musculoskeletal perspectives. Part 1: clinical assessment. Equine Vet. Educ. 28, 284–293. Dyson, S., Carson, S. and Fisher, M. 2015. Saddle fitting, recognizing an Ill-fitting saddle and the consequences of an Ill-fitting saddle to horse and rider. Equine Vet. Educ. 27, 533–543. Dyson, S. and Murray, R. 2003. Pain associated with the sacroiliac joint region: a clinical study of 73 horses. Equine Vet. J. 35, 240–245. Engeli, E. and Haussler, K. 2011. Review of injection techniques targeting the sacroiliac region in horses. Equine Vet. Educ. 24, 529–541. Findley, J. and Singer, E. 2015. Equine back disorders 1. clinical presentation, investigation and diagnosis. Practice 37, 456–467. Fonseca, B.P.A., Alves, A.L.G., Nicoletti, J.L.M., Thomassian, A., Hussni, C.A. and Mikail, S. 2006. Thermography and ultrasonography in back pain diagnosis of equine athletes. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 26, 507–516. Girodroux, M, Dyson, S. and Murray, R. 2009. Osteoarthritis of the thoracolumbar synovial intervertebral articulations: clinical and radiographic features in 77 horses with poor performance and back pain. Equine Vet. J. 14, 130–138. Greve, L. and Dyson, S.J. 2014. The Interrelationship of lameness, saddle slip and back shape in the general sports horse population. Equine Vet. J. 46, 687–694. Henson, F.M.D., Lamas, L., Knezevic, S. and Jaffcott, L.B. 2007. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the supraspinous ligament in a series of ridden and unridden horses and horses with unrelated back pathology. BMC Vet. Res. 3, 3. Jeffcott, L.B. 1993. Ruckenproblems beim athleten Pferd 2. 223-236Mogliche Differentialdiagnosen Und Therapiemethoden. Pferdeheilkunde 9, 223–236. Jeffcott, L.B. 1980. Disorders of the thoracolumbar spine of the horse. A survey of 443 cases. Equine Vet. J. 2, 197–210. Kent Allen, A., Johns, S., Hyman, S.S., Acvim,D., Sislak,M.D. and Amory, J. 2010. How to diagnose and treat back pain in the horse. AAEP Proc. 56, 384–388. Landman,M.A.A.M., DeBlaauw, J.A., VanWeeren, P.R. and Hofland, L.J. 2004. Field study of the prevalence of lameness in horses with back problems. Vet. Rec. 155, 165–168. Licka, T. and Peham, C. 1998. An objective method for evaluating the flexibility of the back of standing horses. Equine Vet. J. 30, 412–415. Martin, Jr., B.B.r. and Klide,A.M. 1987. Treatment of chronic back pain in horses. stimulation of acupuncture points with a low powered infrared laser. Vet. Surg. 16, 106–110. Mayaki, M.A., Intan-Shameha, A.R., Noraniza, M.A., Mazlina, M., Adamu, L. and Abdullah, R. 2019. Clinical investigation of back disorders in horses: a retrospective study (2002-2017). Vet. World 12 (3), 377–381. Peham, C., Frey, A., Licka, T. and Scheidl, M. 2001. Evaluation of the EMG activity of the long back muscle during induced back movements at stance. Equine Vet. J. 33, 165–168. Ridgway, K. and Harman, J. 1999. Equine back rehabilitation. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 15, 263–280. Shokry, M. 2016. A simple technique of sacroiliac regional analgesia and therapy in show jumping horses. Austin. J. Anesthesia Analgesia 3(1), 1042. Soroko, M. and Howell, K. 2018. Infrared thermography: current applications in equine medicine. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 60, 90–96. Turner, T.A. 2011. Overriding spinous processes (“Kissing Spines”) in horses: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome in 212 cases. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, San Antonio, TX, 2011. Walmsley, J.P., Pettersson, H., Winberg, F.G. and McEvoy, F. 2010. Impingement of the dorsal spinous processes in, two hundred and fifteen horses: case selection, surgical technique and results. Equine Vet. J. 34, 23–28. Wong, D., Miles, K. and Sponseller, B. 2006. Congenital Scoliosis in a quarter horse filly. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 47, 279–282. Zimmerman, M., Dyson, S. and Murray, R. 2012. Close impinging and overriding spinous processes in the thoracolumbar spine: the relationship between radiological and scintigraphic findings and clinical signs. Equine Vet. J. 44, 178–184. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Shokry M, Ali LMB, El-sharkawy M. Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(3): 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 Web Style Shokry M, Ali LMB, El-sharkawy M. Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=231519 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Shokry M, Ali LMB, El-sharkawy M. Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(3): 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Shokry M, Ali LMB, El-sharkawy M. Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(3): 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 Harvard Style Shokry, M., Ali, . L. M. B. & El-sharkawy, . M. (2025) Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. Open Vet. J., 15 (3), 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 Turabian Style Shokry, Mohamed, Lutfi M. Ben Ali, and Mohamed El-sharkawy. 2025. Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (3), 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 Chicago Style Shokry, Mohamed, Lutfi M. Ben Ali, and Mohamed El-sharkawy. "Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Shokry, Mohamed, Lutfi M. Ben Ali, and Mohamed El-sharkawy. "Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses." Open Veterinary Journal 15.3 (2025), 1480-1487. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Shokry, M., Ali, . L. M. B. & El-sharkawy, . M. (2025) Relationship between back pain and poor performance in show jumping athletic horses. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (3), 1480-1487. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i3.37 |