| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(5): 2066-2072 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(5): 2066-2072 Research Article Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central MediterraneanAbdulmaula Hamza*, Amal Abdel-Aziz Abunaqassa, Nusaiba Adel Al-Qrew and Noura Milad SalehBiology Department, Faculty of Education Tripoli, University of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya *Corresponding Author: Abdulmaula Hamza, Biology Department, Faculty of Education Tripoli, University of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya. Email: abd.hamza [at] uot.edu.ly Submitted: 21/01/2025 Revised: 04/04/2025 Accepted: 14/04/2025 Published: 31/05/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

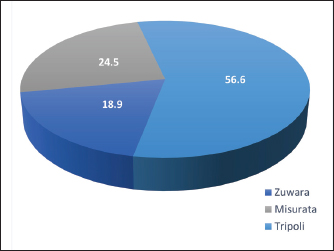

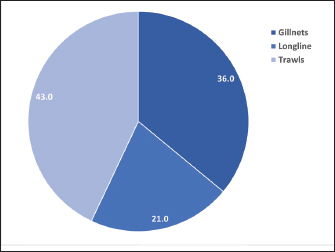

ABSTRACTBackground: Angel sharks (Squatina spp.) in the Mediterranean Sea are critically endangered, and there is a significant knowledge gap regarding their populations in Libyan waters. Aim: This study aimed to assess the status of Angel sharks in Libyan waters by integrating local ecological knowledge (LEK) from artisanal fishers with novel morphometric data. Methods: Structured interviews were conducted with 53 artisanal fishers at the Tripoli fishing port (April–May 2022) to gather LEK on Angel shark distribution, abundance, and threats. Morphometric measurements were collected from seven Angel shark specimens that landed during the study period. Results: Fishers encountered all three Mediterranean Angel shark species (Squatina squatina, Sesbania aculeata, and Squatina oculata) across several Libyan coastal areas (Tripoli, Misurata, Zuwara, Tajoura, and Qarabuli). Annual catch estimates of five or more Angel sharks per fisher were reported, primarily from depths of 10–300 m (mean: 124.02 m). Reported total lengths ranged from 15 to 200 cm, with the majority being between 15 and 100 cm. Trawling (43%), bottom gillnets (36%), and longlines (21%) were the main fishing methods associated with Angel shark captures. A significant positive correlation was found between distance from the coast and fishing depth (Spearman’s r<sub>s</sub>=0.69, p < 0.001). Morphometric data included: S. squatina (n=3; TL: 46–80 cm; weight: 884.0–6395.0 g), S. aculeata (n=1; TL: 66 cm; weight: 1,884.0 g), and S. oculata (n=3; TL: 44–52 cm; weight: 634.0–959.0 g). Fishers identified marine pollution, overfishing, illegal fishing practices, and inadequate enforcement as major threats to the Angel shark population. Conclusion: This study provides critical baseline information on the abundance and distribution of angel sharks in Libyan waters, highlighting their continued presence and vulnerability. The findings underscore the urgent need for targeted conservation actions. This includes stock assessments, habitat protection, and fisheries management measures to ensure the long-term survival of these critically endangered species in the region. Keywords: Angel sharks, Squatina spp., Libya, Local Ecological Knowledge, Morphometrics, Conservation, Fisheries, Mediterranean Sea. IntroductionAngel sharks (Squatina spp.) represent a unique and critically endangered group of benthic elasmobranchs, which are characterized by flattened bodies, cryptic coloration, and ambush predation strategies. (Compagno et al. 2005). These adaptations made them highly efficient predators in their marine habitats (Ellis et al., 2021). Globally, 23 species of Angel sharks have been identified, all facing significant threats from bycatch in bottom-fishing gear, habitat degradation, and overfishing (Dulvy et al., 2021; Long et al., 2021). In the Mediterranean Sea, the three species of the Angel shark—the common Angel shark (Squatina squatina), the smooth-back Angel shark (Squatina oculata), and the sawback Angel shark (Sesbania aculeata)—have experienced dramatic population declines, leading to their classification as critically endangered on the IUCN red list (Gordon et al., 2019). Once common across Mediterranean fisheries, these species now persist in only a few localized areas, with records becoming increasingly scarce (Damalas and Vassilopoulou, 2011; Fortibuoni et al., 2016). The Mediterranean Angel Shark exemplifies the challenges facing regional marine biodiversity. Historical records indicate that these sharks were once widespread throughout the northern Adriatic, Aegean, and Tyrrhenian Seas. However, over the past six decades, targeted fisheries and incidental bycatch have significantly decimated populations of these species (Ligas et al., 2013; Follesa et al., 2019). Today, isolated reports from regions such as the Gulf of Gabès and the Tyrrhenian Sea indicate small, remnant populations, highlighting the need for urgent conservation measures (Saidi et al., 2023). These patterns mirror broader trends in global elasmobranch decline driven by unsustainable fishing practices, habitat loss, and insufficient management frameworks (Dulvy et al., 2021). Libyan waters, located within area 21 of the Southern Ionian Sea in the GFCM subregion, host a significant proportion of Mediterranean elasmobranch diversity, with over 74 species reported (UNEP-MAP RAC/SPA, 2005). However, systematic data on Squatina species in this region are (SOS, 2020) scarce. Earlier records identified S. squatina and S. aculeata (Hureau and Monod, 1973; Zupanovic and El-Buni, 1982), while later studies confirmed the presence of S. oculata (Sogreah, 1977). A recent national checklist documented 59 elasmobranch species in Libya (Shakman et al., 2023). The absence of detailed studies hampers efforts to understand population trends, spatial distributions, and threats. However, anecdotal evidence from local artisanal fishers suggests that Angel sharks continue to inhabit Libyan waters, albeit under growing pressure from marine pollution, illegal fishing practices, and bycatch. Local ecological knowledge (LEK) is a promising approach to address data gaps in regions with limited scientific monitoring (Figus et al., 2017). By integrating Fisher observations with direct biological measurements, LEK provides a cost-effective and community-driven method for assessing species distribution, abundance, and threats (Berkström et al., 2019; Colloca et al., 2020). This study combines LEK with morphometric measurements to present the first comprehensive assessment of Angel sharks in Libya. The findings will inform conservation strategies and establish baseline data crucial for the sustainable management of critically endangered species. Materials and MethodsData collection through interviewsLEK was collected through structured interviews with fishers at the Tripoli fishing port between April 15 and May 15, 2022. A total of 53 fishers were interviewed, all of whom were regularly engaged in fishing activities using either artisanal fishing vessels or trawlers. Before each interview, participants were provided with an information sheet outlining the research objectives and were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. Informed consent was obtained verbally from all participants. The interviews were conducted in person using a standardized questionnaire that included both closed and open-ended questions. Questions focused on fishing practices, including fishing seasons, gear used, primary fishing grounds, and economic aspects related to Angel sharks. Participants were also asked about their encounters with Angel sharks, including their frequency, location (distance from shore and depth), size of captured individuals, bottom type, and perceived trends in abundance. Color illustrations were used to confirm the identification of the three mediterranean angel shark species (S. squatina, S. aculeata, and S. oculata). Recreational fishers were excluded from the study. Morphometric analysisMorphometric measurements were taken from seven Angel shark specimens: S. squatina (n=3), S. aculeata (n=1), and S. oculata (n=3). These specimens represent the first morphometric data of angel sharks in Libya. Twenty-two standard body measurements were recorded for each specimen, following the methods outlined by Bass et al. (1975) (Table 1). All measurements were made to the nearest millimeter using calipers. The mouth width was measured as the distance between the inner edges of the labial furrows. Data analysisQuantitative data obtained from the questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize trends in fisher-reported observations. In contrast, open-ended responses were analyzed qualitatively to provide context and explore fishers’ perceptions of Angel shark populations and the threats they face. Additionally, Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess the relationship between the distance from the coast and fishing depth. Statistical analyses were performed using MS Excel® and the R software environment (R Core Team, 2024) ensuring reproducibility and accuracy of findings. Ethical approvalNot needed for this study. ResultsFisher’s encounters and perceptionsAll the interviewed fishers (n=53) reported encountering Angel sharks in their fishing areas. While all respondents were able to identify Squatina squatina, the other two species, S. aculeata and S. oculata, were not consistently recognized, likely due to their lower capture frequency. The primary fishing areas where Angel sharks were encountered were Tripoli (56.6%), Misurata (24.5%), and Zuwara (18.9%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Fishing areas used in fishing Angel sharks in Tripoli port, Libya. The majority of fishers (69.8%, n=37) reported capturing five or more Angel sharks in the 12 months preceding the interviews. However, all reported captures were incidental bycatch because there are no targeted fisheries for angel sharks in Libya. Fishers reported that encounter depths varied depending on the fishing gear used. Users of Artisanal gear encountered Angel sharks at shallow depths as little as 10 m, while trawlers reported encounters at depths of up to 200–300 m. The overall average capture depth was 124.02 m. Similarly, distances from the coast where Angel sharks were encountered ranged from 3 nautical miles (for artisanal gear) to 200 nautical miles (for trawlers), with an overall average of 60.27 nautical miles. A strong positive correlation was found between distance from the coast and fishing depth (Spearman’s rs=0.69, p < 0.001), indicating that Angel sharks are more frequently encountered in deeper, offshore waters.

Fig. 2. Fishing gear types used for Angel Shark fishing in Tripoli, Libya.

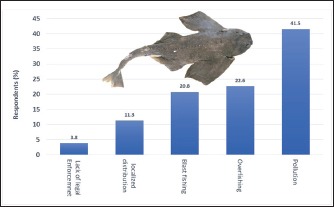

Fig. 3. Causes of Angel Shark decline based on Fisher’s opinion. The total length (TL) of the captured angel sharks ranged from 15 to 200 cm. The most frequently reported size class was 15–100 cm (64.2%), followed by 101–110 cm (18.9%) and 110–200 cm (17.0%). Fishers reported encountering Angel sharks most frequently over rocky-sandy substrates, followed by sandy bottoms. Among fishing gears, trawling was the most cited method associated with the capture of Angel sharks (43.2%), followed by bottom gillnets (35.8%) and longlines (20.9%) (Fig. 2). Perceived decline in Angel SharksAll respondents reported a perceived decline in Angel shark catches in recent years. The primary factors attributed to this decline included increased land-based marine pollution (41.5%), particularly untreated sewage along the Tripoli coast, which intensified over the past decade. Other contributing factors cited were overfishing (22.6%), destructive practices like dynamite fishing (20.8%), localized distribution of Angel sharks (11.3%), and insufficient enforcement of fisheries regulations (3.8%) (Fig. 3). Two fishers provided photographs of S. squatina specimens they had captured (Fig. 4).

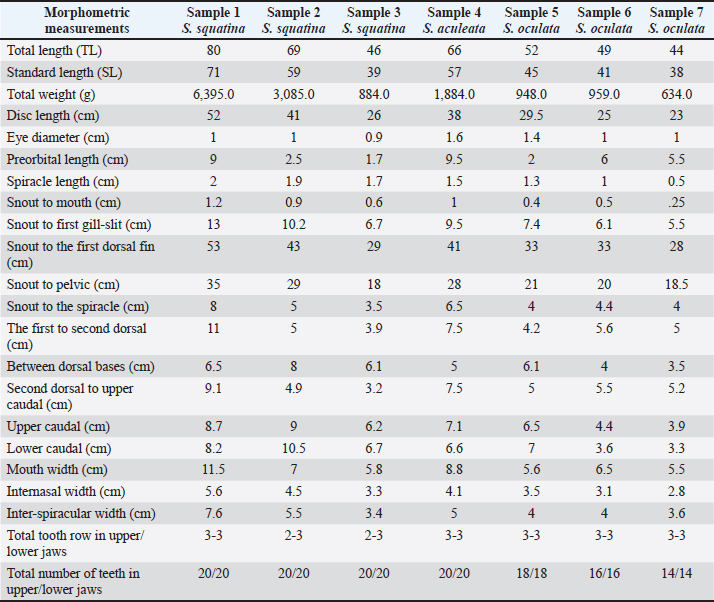

Fig. 4. Some common Angel sharks were photographed by fishers in Tripoli waters. Morphometric dataMorphometric measurements were obtained from seven Angel shark specimens captured in Tripoli waters, including S. squatina (n=3), S. aculeata (n=1), and S. oculata (n=3) (Table 1).

Variations in body proportions, such as the distance from the snout to the first dorsal fin and from the snout to the pelvic fin, were observed among the three species, reflecting interspecific differences in body morphology within the Squatina genus. S. squatina consistently exhibited larger body dimensions compared to the other two species. The number of tooth rows was relatively consistent among the species. Notably, all measured specimens were juveniles or sub-adults, suggesting that ongoing trawling activities disproportionately impact younger age classes and pose a significant threat to the population structure of these species. Table 1. Morphometric measurements of seven Angel shark specimens caught off the Tripoli coast, Libya.

DiscussionThis study provides one of the first insights into the status of the Angel shark (Squatina spp.) in Libyan waters by integrating LEK with fisheries data. The findings reveal key information about their distribution, catch characteristics, and threats, highlighting the Tripoli region as a potential hotspot for Angel sharks, particularly S. squatina, which was the most frequently identified species by the interviewed fishers. The reported encounters in Misrata, Zuwara, Tajoura, and Garabulli further indicate the widespread distribution of these species along the Libyan coast. Similar patterns have been observed in neighbouring Tunisia, where S. oculata has been reported in the north (Rafrafi-Nouira et al., 2022). In the Gulf of Gabès, surveys indicated the rare occurrence of S. aculeata and S. oculata (Saidi et al., 2023). Given the shared continental shelf between Libya and Tunisia, the conservation status of these species is likely similar in both countries, which could inform conservation strategies across the region. One of the most concerning findings is the prevalence of juvenile Angel sharks in the reported catches. The majority of captured individuals fell within the 15–100 cm TL size class, suggesting that immature individuals dominate the population in these areas. This, along with the observed correlation between fishing depth and distance from the shore, indicates that coastal areas may serve as important nursery habitats for these species. The capture of juveniles before reproductive maturity could severely impact population recruitment and long-term viability (Awruch et al., 2008). Similarly, concerns regarding the impact of fishing on juvenile Angel sharks have been raised in other parts of the Mediterranean (Giovos et al., 2022). The preference for rocky and sandy bottom habitats of Angel sharks aligns with previous studies on their habitat associations (Bakiu et al., 2020; Barker et al., 2022). This information can aid in the identification of critical habitats and the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) to safeguard key Angel shark grounds. Additionally, the predominance of trawling as the primary fishing gear associated with the capture of Angel sharks highlights the significant risk of bycatch, which could negatively impact these vulnerable species. Although there is no targeted fishery for Angel sharks in Libya, the incidental capture of these species in bottom trawls, gillnets, and longlines still contributes to population decline, as observed in other Mediterranean regions (Dulvy et al., 2017). Fishers’ perceptions of the declining abundance of Angel sharks, attributed primarily to marine pollution, overfishing, and illegal fishing practices, align with broader threats to marine biodiversity in the Mediterranean (Coll et al., 2010; FAO, 2020). The increase in land-based pollution, particularly the discharge of untreated sewage along the Tripoli coast, is a serious concern that requires urgent attention. Moreover, destructive fishing practices, such as dynamite fishing, not only directly harm Angel shark populations and degrade their habitats. The lack of effective fisheries regulations and enforcement exacerbates these threats, making it imperative to improve governance and monitoring mechanisms. Although the morphometric data presented in this study are based on a small sample size, they provide valuable baseline information for future assessments of the Angel shark populations in Libya. The observed variations in body proportions among the three Squatina species are consistent with known interspecific differences within the genus. The capture of these specimens in trawls, particularly juvenile or subadult size, highlights the potential threat that fishing activities pose to the population structure of these species. While Libya’s relatively small fishing fleet has historically maintained robust fish stocks, the increasing use of unsustainable fishing methods, such as extensive bottom trawling, threatens to undermine this stability (Bradai et al., 2022). Conservation concerns and actionable recommendationsThe findings of this study underscore the urgent need for targeted conservation measures to protect Angel sharks in Libya. A crucial first step is the development and implementation of a national elasmobranch conservation plan, created in collaboration with local fishers and other relevant stakeholders. This plan should include tested measures to reduce bycatch, such as gear modifications (e.g., bycatch-reducing devices) and spatial or temporal closures in areas of high Angel shark abundance. In addition, addressing the threats posed by marine pollution and illegal fishing practices is crucial. Strengthening the enforcement of existing regulations and raising awareness among fishers and the general public about the importance of Angel shark conservation are essential components of a comprehensive strategy. In particular, enforcement should focus on halting the sale of endangered species at fish markets (Fig. 5). Establishing well-managed MPAs along the Libyan coast, particularly in areas identified as important habitats for Angel shark and other elasmobranch species, is also a priority. Two candidate areas, the Tripolitania coast and the Gulf of Sirte (Sidra) waters, have recently been proposed as important shark and ray areas (IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, 2023), which would help the national authorities to declare them as MPAs. These MPAs not only protect Angel shark populations but also support local fishers by providing refugia. This could allow for the potential spillover of adults into adjacent fish areas. Future research should focus on expanding the collection of morphometric and biological data, including reproductive biology and feeding ecology. This will help us better understand the population dynamics and ecological requirements of Angel sharks in the region.

Fig. 5. Common Angel shark Squatina squatina on display at Tripoli fish market (A Hamza ©). Integrating ongoing LEK monitoring with scientific surveys can provide a comprehensive understanding of the status of Angel sharks, enabling more adaptive and effective management strategies. ConclusionThis study confirms that critically endangered Angel sharks persist in Libyan waters and face severe threats. Local fishers’ knowledge, combined with our morphometric data, reveals that all three Mediterranean species are present, mainly juveniles caught as bycatch. Tripoli appears to be a key area, underscoring this for effective protection. Declining catches, linked to pollution and destructive fishing, demand immediate action. The national elasmobranch action plan must be effectively implemented and strengthened, focusing on these threats. The key priorities are bycatch reduction, habitat protection, and prohibition of illegal fishing practices. Community engagement remains crucial. The identified Important Shark and Ray Areas must be legally protected as a priority. AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and valuable suggestions, which helped strengthen this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to the fishermen of Tripoli Port who generously shared their time and expertise during the interviews. Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant. Authors’ contributionsAbdulmaula Hamza led the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, and supervision of the study and was responsible for writing, review, and editing. Amal Abdel-Aziz Abunaqassa, Nusalba Adel Al-Qrew, and Noura Milad Saleh contributed to the field and lab investigations, methodology development, and visualization of the research results. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Data availabilityThe manuscript contains all the data supporting the findings of this study. Any additional information needed is obtainable from the corresponding author upon justifiable request. ReferencesAwruch, C., Nostro, F., Somoza, G. and Giacomo, E. 2008. Reproductive biology of the angular Angel shark Squatina guggenheim (chondrichthyes: squatinidae) off patagonia (Argentina, southwestern Atlantic). Cienc. Mar. 34(1), 17–28; doi:10.7773/cm.v34i1.1232 Bakiu, I., Xharra, B., Colatosti, R. and Gancio, R. 2020. Angel Shark (Squatina squatina) occurrence and condition in the Albanian coast and offshore waters. Aquat. Conserv. 33(S2), 243–255; doi:10.1002/aqc.3429 Barker, J., Davies, J., Goralczyk, M., Patel, S., O’Connor, J., Evans, J., Sharp, R., Gollock, M., Wood, F.R., Rosindell, J., Bartlett, C., Garner, B.J., Jones, D., Quigley, D. and Wray, B. 2022. The distribution, ecology and predicted habitat use of the critically endangered angel shark (Squatina squatina) in coastal waters of Wales and the central Irish Sea. J. Fish Biol. 101(3), 640–658; doi:10.1111/jfb.15133 Bass, A.J., d’Aubrey, J.D. and Kistnasamy, N. 1975. Sharks of the east coast of Southern Africa. V. The families Hexanchidae, Chlamydoselachidae, Heterodontidae, Pristiophoridae, and Squatinidae. Invest. Rep. Oceanogr. Res. Inst. 43, 1–50. Berkström, C., Papadopoulos, M., Jiddawi, N.S. and Nordlund, L.M. 2019. Fishers’ local ecological knowledge (LEK) on connectivity and seascape management. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 130; doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00130 Bradai, M.N., Enajjar, S. and Saidi, B. 2022. Sharks’ status in the Mediterranean sea urgent awareness is needed. In: Sharks-past, present and future. London, UK: IntechOpen; doi:10.5772/intechopen.108162 Coll, M., Piroddi, C., Steenbeek, J., Kaschner, K., Ben Rais Lasram, F., Aguzzi, J., Ballesteros, E., Bianchi, C.N., Corbera, J., Dailianis, T., Danovaro, R., Estrada, M., Froglia, C., Galil, B.S., Gasol, J.M., Gertwagen, R., Gil, J., Guilhaumon, F., Kesner-Reyes, K., Kitsos, M.S., Koukouras, A., Lampadariou, N., Laxamana, E., López-Fé de la Cuadra, C.M., Lotze, H.K., Martin, D., Mouillot, D., Oro, D., Raicevich, S., Rius-Barile, J., Saiz-Salinas, J.I., San Vicente, C., Somot, S., Templado, J., Turon, X., Vafidis, D., Villanueva, R. and Voultsiadou, E. 2010. The biodiversity of the mediterranean sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS One 5(8), e11842; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011842 Colloca , F., Carrozzi, V., Simonetti, A. and Lorenzo, M. 2020. Using local ecological knowledge of fishers to reconstruct abundance trends of elasmobranch populations in the strait of sicily. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 508; doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00508 Compagno, L.J.V., Dando, M. and Fowler, S. 2005. Sharks of the world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Damalas, D. and Vassilopoulou, V. 2011. Chondrichthyan by-catch and discards in the demersal trawl fishery of the central Aegean Sea (Eastern Mediterranean). Fish. Res. 108(1), 142–152; doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2010.12.012 Dulvy, N.K., Simpfendorfer, C.A., Davidson, L.N.K., Fordham, S.V., Bräutigam, A., Sant, G. and Welch, D.J. 2017. Challenges and priorities in shark and ray conservation. Curr. Biol. 27(11), R565–R572; doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.038 Dulvy, N.K., Pacoureau, N., Rigby, C.L., Pollom, R.A., Jabado, R.W., Ebert, D.A., Finucci, B., Pollock, C.M., Cheok, J., Derrick, D.H. and Herman, K.B. 2021. Overfishing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Curr. Biol. 31(21), 4773–4787; doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.062 Ellis, J.R., Barker, J., McCully Phillips, S.R., Meyers, E.K. and Heupel, M. 2021. Angel sharks (Squatinidae): a review of biological knowledge and exploitation. J. Fish Biol. 98(3), 592–621; doi:10.1111/jfb.14613 FAO. 2020. The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2020. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean, Rome, Italy: FAO; doi:10.4060/cb2429en Figus, E., प्रदेशसे, A., Battaglia, P., Russo, T., D’Onghia, G. and Sion, L. 2017. Local ecological knowledge and scientific data on occurrence of the Common Gurnard (Chelidonichthys lucerna) (Actinopterygii: Perciformes: Triglidae) in the north-western Ionian Sea (central Mediterranean Sea). Acta Ichthyol. Pisc. 47(3), 291–296; doi:10.3750/AIEP/02194 Follesa, M.C., Marongiu, M.F., Zupa, W., Bellodi, A., Cau, A., Cannas, R., Colloca, F., Djurovic, M., Isajlovic, I., Jadaud, A., Manfredi, C., Mulas, A., Peristeraki, P., Porcu, C., Ramirez-Amaro, S., Salmerón Jiménez, F., Serena, F., Sion, L., Thasitis, I., Cau, A. and Carbonara, P. 2019. Spatial variability of Chondrichthyes in the northern Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 83(S1), 81–100; doi:10.3989/scimar.04998.23A Fortibuoni, T., Borme, D., Franceschini, G., Giovanardi, O. and Raicevich, S. 2016. Common, rare or extirpated? shifting baselines for common Angel shark, Squatina squatina (Elasmobranchii: Squatinidae), in the Northern Adriatic Sea (Mediterranean Sea). Hydrobiologia 772, 247–259; doi:10.1007/s10750-016-2671-4 Giovos, I., Katsada, D., Naasan Aga Spyridopoulou, R., Poursanidis, D., Doxa, A., Katsanevakis, S., Kleitou, P., Oikonomou, V., Minasidis, V., Ozturk, A.A., Petza, D., Sini, M., Cigdem Yigin, C., Meyers, E.K.M., Barker, J. and Jiménez-Alvarado, D. 2022. Strengthening angel shark conservation in the Northeastern Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10(2), 269; doi:10.3390/jmse10020269 Gordon, C.A., Hood, A.R., Al Mabruk, S.A.A., Barker, J., Bartolí, A., Ben Abdelhamid, S., Bradai, M.N., Dulvy, N.K., Fortibuoni, T., Giovos, I. and Jimenez Alvarado, D. 2019. Mediterranean Angel Sharks: regional action plan. Plymouth, England: The Shark Trust, p: 36. Hureau, J.C. and Monod, T. 1973. Check-list of the fishes of the north-eastern Atlantic and of the Mediterranean. Paris, France: UNESCO. IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. 2023. Important shark and ray areas regional expert workshop report: mediterranean and black seas. May 2023. Thessaloniki, Greece: IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, pp: 33. Ligas, A., Osio, G.C., Sartor, P., Sbrana, M. and De Ranieri, S. 2013. Long-term trajectory of some elasmobranch species off the Tuscany coasts (NW Mediterranean) from 50 years of catch data. Sci. Mar. 77(1), 119–127; doi:10.3989/scimar.03654.21C Long, D.J., Ebert, D.A., Tavera, J., Acero, P.A. and Robertson, D.R. 2021. Squatina mapama n. sp., a new cryptic species of Angel shark (Elasmobranchii: Squatinidae) from the southwestern Caribbean Sea. J. Ocean Sci. Found. 38, 113–130; doi:10.5281/zenodo.5806693 R Core Team. 2024. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. [Online] Available via https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed 10 Dec 2024). Rafrafi-Nouira, S., Chérif, M., Reynaud, C. and Capapé, C. 2022. Captures of the rare smoothback Angel shark Squatina oculata (Squatinidae) from the Tunisian coast (central Mediterranean Sea). Thalassia Salent. 44, 9–16; doi:10.1285/i15910725v44p9 Saidi, B., Enajjar, S. and Bradai, M.N. 2023. Vulnerability of elasmobranchs caught as bycatch in the grouper longline fishery in the Gulf of Gabès, Tunisia. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 24(1), 142–155; doi:10.12681/mms.27483 Shakman, E.A.M., Etayeb, K.S.E., Siafenasar, A., Shefern, A., Elmgwashi, A., Al Hajaji, M., Benghazi, N.B., Abdalha, A.B., Aissi, M. and Serena, F. 2023. National inventory and status of Chondrichthyes in the South Mediterranean Sea (Libyan Coast). Biodiv. J. 3(4), 459–480; doi:10.31396/Biodiv. Jour.2023.14.3.459.480 Sogreah. 1977. Trawl fishing ground survey off the tripolitanian coast. Final Report. Grenoble, France: Sogreah, Part V: 1–44. SOS (Save our seas foundation). 2020. A lifeline for Libya’s Angel sharks [Online]. Geneva, Switzerland. Available via http://www.saveourseas.com/project/a-lifeline-for-libyas-Angel-sharks/ (Accessed 10 Dec 2024). UNEP-MAP RAC/SPA. 2005. Chondrichthyan fishes of Libya: proposal for a research programme. By Seret, B. (Ed.). Tunis, Tunisia: RAC/SPA, P: 31. Zupanovic, S. and El-Buni, A.A. 1982. A contribution to demersal fish studies off the Libyan coast. Bull. Mar. Res. Cent. 3, 77–122. Tripoli Libya. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Hamza AA, Abunaqassa AA, Al-qrew NA, Saleh NM. Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(5): 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 Web Style Hamza AA, Abunaqassa AA, Al-qrew NA, Saleh NM. Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=239136 [Access: January 24, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Hamza AA, Abunaqassa AA, Al-qrew NA, Saleh NM. Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(5): 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Hamza AA, Abunaqassa AA, Al-qrew NA, Saleh NM. Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 24, 2026]; 15(5): 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 Harvard Style Hamza, A. A., Abunaqassa, . A. A., Al-qrew, . N. A. & Saleh, . N. M. (2025) Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. Open Vet. J., 15 (5), 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 Turabian Style Hamza, Abdulmaula Abdulmagid, Amal Abdel-aziz Abunaqassa, Nusaiba Adel Al-qrew, and Noura Milad Saleh. 2025. Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (5), 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 Chicago Style Hamza, Abdulmaula Abdulmagid, Amal Abdel-aziz Abunaqassa, Nusaiba Adel Al-qrew, and Noura Milad Saleh. "Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Hamza, Abdulmaula Abdulmagid, Amal Abdel-aziz Abunaqassa, Nusaiba Adel Al-qrew, and Noura Milad Saleh. "Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean." Open Veterinary Journal 15.5 (2025), 2066-2072. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Hamza, A. A., Abunaqassa, . A. A., Al-qrew, . N. A. & Saleh, . N. M. (2025) Artisanal fisher ecological knowledge with morphometric measurements of Angel Sharks form Libya, Central Mediterranean. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (5), 2066-2072. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.23 |