| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2457-2470 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2457-2470 Research Article Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharideMaryam Saleh Alhumaidi1*1Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Hafr Al Batin, Hafr Al Batin, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia *Corresponding Author: Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Hafr Al Batin, Hafr Al Batin, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Email: maryamalhumaidi [at] uhb.edu.sa Submitted: 28/01/2025 Revised: 27/04/2025 Accepted: 17/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

AbstractBackground: Campylobacteriosis is a common bacterial diarrheal illness frequently associated with poultry consumption and represents a significant problem for public health and the economy. The increasing drug resistance associated with Campylobacter jejuni emphasizes the imperative nature of the situation. The diverse bioactive compounds found in ginger (Zingiber officinale), such as proteins hold a promising and advancing anticampylobacteriosis research. Aim: This study investigated the potential of ginger-derived peptides to target key bacterial components involved in antibiotic resistance and virulence. Methods: Using computational modeling approaches for modeling ginger-derived peptides and different parameters and targeting efflux pumps (CmeABC and CmeC proteins) and beta-1,3-galactosyltransferase and Beta-1,3 galactosyltransferase (CgtE) involved in lipooligosaccharide (LOS) biosynthesis. Results: Physicochemical analysis revealed varied properties for targeting peptides. The results suggest that ginger-derived peptides, particularly AtpH-2, could interact with components of the efflux pump, disrupting bacterial membrane function and enhancing antimicrobial efficacy. Furthermore, the interaction between AtpH-2 and LOS biosynthesis enzymes suggests a possible disruption of LOS production. Conclusion: These findings indicate that ginger-derived peptides, especially AtpH-2, could synergistically weaken Campylobacter defenses by interfering with both efflux pump activity and LOS biosynthesis, offering a promising approach for developing novel antibacterial strategies against this zoonotic pathogen. Further research is warranted to elucidate the precise mechanisms of action and validate these in silico predictions. Keywords: Zoonotic pathogen, Efflux pump, Lipooligosaccharide, Antimicrobial peptides, Zingiber officinale, Computational modeling. IntroductionHuman infections with the microaerobic foodborne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni result in a range of gastrointestinal and, in some cases, neurological diseases. While C. jejuni infection commonly results in distress of diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramping (Kaakoush et al., 2015), certain strains are also associated with the development of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), a form of flaccid paralysis (Nyati and Nyati, 2013). Chickens are a natural reservoir and the main source of human C. jejuni infections (Burnham and Hendrixson, 2018). New natural products with demonstrated antimicrobial activity against C. jejuni represent promising therapeutic candidates for treating both human and avian populations. A wide range of strategies can prevent bacteria from the effects of antibiotics (Zhang et al., 2024). Bacteria utilize efflux pumps as a key defense against antibiotics, contributing to both intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance. Particularly important are resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pumps, which are tripartite systems spanning the bacterial cell envelope and actively expel a broad range of antimicrobials and toxins (Guillaume et al., 2004; Nikaido et al., 2012). CmeABC is the main efflux pump in C. jejuni. The genes encoding the inner membrane transporter (CmeB), periplasmic fusion protein (CmeA), and outer membrane protein (CmeC) are organized in a three-gene operon that produces the CmeABC efflux pump (Lin et al., 2002; Poole, 2005). CmeR is a protein that acts as a transcriptional regulator for the CmeABC transporter (Guo et al., 2008). Mutations in CmeR weaken CmeR’s ability to attach. This reduced binding results in higher levels of CmeABC production (Lin et al., 2005). High levels of molecular variation in virulence factors such as lipooligosaccharide (LOS), capsules, and flagellin are crucial for both C. jejuni survival and pathogenicity-linked properties, including bacterial chemotaxis, motility, attachment, invasion, survival, and spread to deeper tissue (Parkhill et al., 2000; Tegtmeyer et al., 2012). The LOS in the outer membrane of C. jejuni lacks the O-antigen found in the lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of many gram-negative bacteria. In some strains, LOS binds with sialic acid, creating a structure that mimics the ganglioside structure in human neurons (St Michael et al., 2002; Karlyshev et al., 2005). This molecular mimicry is a central factor in the development of GBS in humans (Brunner et al., 2018). Targeting the biosynthesis of LOS could facilitate the development of novel treatments and reduce the virulence addressing the rising problem of antibiotic resistance in campylobacteriosis. As integral components of plant innate immunity, plant antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) isolated from diverse plant tissues display antimicrobial activity against phytopathogens and bacteria pathogenic to humans, thus representing promising candidates for antibiotic development (Nawrot et al., 2014). Valued for its diverse applications in both medicinal and culinary practices worldwide, Zingiber officinale (ginger), a rhizomatous herb of the Zingiberaceae family, is recognized for its contributions to both traditional healing systems and global gastronomy. Although ginger is well-known for its flavorful and fragrant qualities, which make it a popular ingredient in many food preparations of curry powders, sauces, breads, and drinks, it also adds a small amount of protein to the diet and increases the value of food as an additive due to its preservative qualities (Opara and Chohan, 2014), numerous health benefits for humans, and significance in food product inspection (Grontved and Pittler, 2013; Ajayi et al., 2013). A previous study suggested that ginger inhibits the growth and virulence of C. jejuni in poultry meat (Wagle et al., 2021). Computational approaches offer efficient screening of small molecules to identify potential drug candidates, thereby accelerating the drug discovery process. Recently, in silico approaches have shown promise in identifying new drugs from peptides and compounds against emerging diseases (Dahab and Aladhadh, 2025) and human immunodeficiency virus (Germoush et al., 2024). Interestingly, advances in bioinformatics have made it possible to closely examine C. jejuni protein interactions (Talukdar et al., 2021), thus accelerating the discovery of new drugs. However, to date, no information on the effects of ginger-derived peptides against C. jejuni has been reported. Although the medicinal and culinary benefits of ginger have been extensively investigated, using computational modeling for detailed analysis of its bioactive peptide constituents has not been previously described; therefore, we conducted a comprehensive study to characterize the peptide profile of ginger for its anti-Campylobacter activities, culminating in the discovery of several novel bioactive peptides exhibiting potential therapeutic properties, particularly relevant in the context of controlling zoonotic diseases. Materials and MethodsDatabase retrieval of C. jejuni protein sequencesFrom UniProt (https://uniprot.org/), we obtained the sequences of two C. jejuni efflux pumps (CmeABC: ID: Q0PBE3, CmeC: ID: E1CJL5) and the beta-1,3-galactosyltransferase (CgtB), and Beta-1,3 galactosyltransferase (cgtE) UniProt ID: Q9F0N0 and Q8KWR0 involved in LOS biosynthesis, respectively (available as Supplementary Material S1). Database retrieval of Z. officinale protein sequencesA search of the UniProt database yielded Z. officinale protein sequences with lengths of 50 amino acids. A total of 27 protein sequences meeting this criterion were saved in FASTA format (Table 1). Protein sequences from Z. officinaleTo investigate the potential of small bioactive peptides, we retrieved 27 protein sequences, each less than 50 amino acids long, from ginger in the UniProt Knowledgebase (https://uniprot.org/). These sequences were subsequently saved in the widely used FASTA format. Computational prediction of antimicrobial activity in Z. officinale peptidesWe used the CAMPR3 web server (http://www.camp3.bicnirrh.res.in/predict/) to predict the antimicrobial activity of proteins derived from ginger. The CAMPR3 server employs a Random Forest Classifier algorithm to categorize the peptides as either AMPs or nonantimicrobial. Computational prediction of allergenicity in filtered Z. officinale peptidesTo ensure the selected AMPs were unlikely to cause allergic reactions, we predicted their allergenicity using the AllerTOP v.2.1 online tool (https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/method.html) (Dimitrov et al., 2014). This step is crucial for further characterization of the AMPs. Physicochemical profiling of Z. officinale peptidesTwo peptides potentially derived from Z. officinale were subjected to in silico physicochemical characterization using the ProtParam tool (https://web. expasy.org/protparam/) on the ExPASy server (Wilkins et al., 1999). The amino acid sequences of AtpH-1 (10 amino acids) and AtpH-2 (17 amino acids) UniProt ID: A0A166IYH9 and A0A286QYA5, respectively, were input into the ProtParam tool. ProtParam calculates various physicochemical properties based on the amino acid sequence. Structure building, refining, and validation of peptides derived from Z. officinaleSince there is currently no publicly available database dedicated specifically to ginger-derived peptides, only two ginger-derived peptides that passed the AMP and allergenicity filters were selected for further bioinformatics analysis. ChimeraX v1.9 software was used to build the 3D structures of these peptides. The structures were then saved in PDB file format for further refinement analysis. The Galaxy web server (https://galaxy.seoklab.org/refine/) was employed for the refinement of the initial peptide structures. The proposed web server utilizes various refinement tools to optimize the geometry and energy of the models. Following refinement, the best-refined structures were subjected to quality assessment using the PEP-FOLD server (https://bioserv.rpbs.univ-paris-diderot. fr/services/PEP-FOLD3/). The proposed server provides a variety of metrics to evaluate predicted protein structures and assess their accuracy. Chimera UCSF 1.17.3 software was used to analyze the Ramachandran plots of the validated peptide models. The Ramachandran plot visually depicts the allowed regions for the phi (φ) and psi (ψ) dihedral angles in a protein structure. This analysis helps identify potential steric clashes or unrealistic conformations within the models. Table 1. Peptides from Zingiber officinale identified in UniProt with less than 50 amino acids.

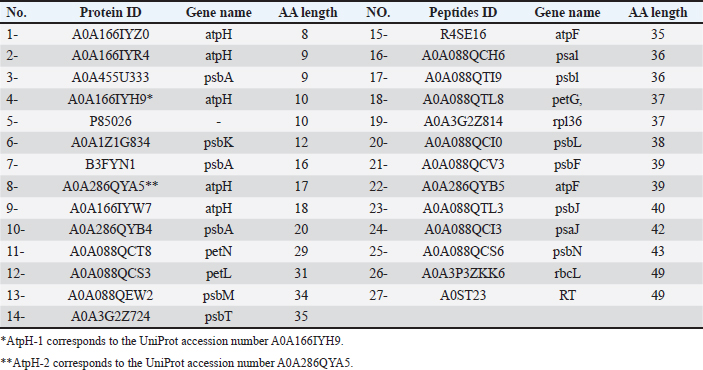

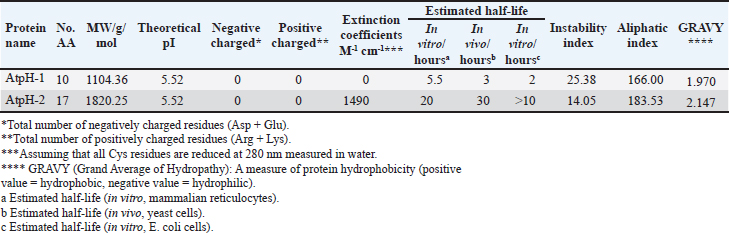

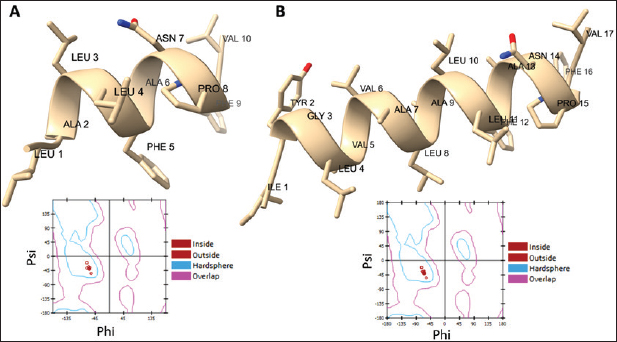

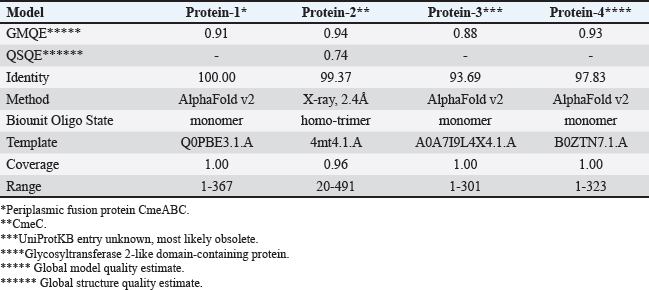

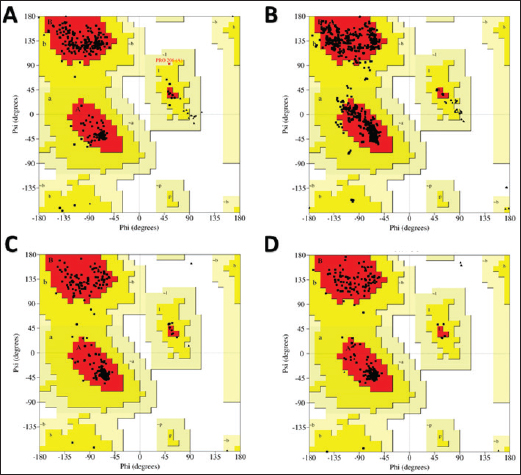

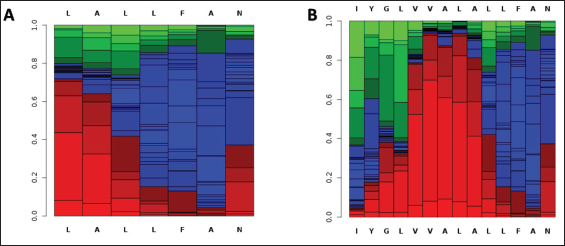

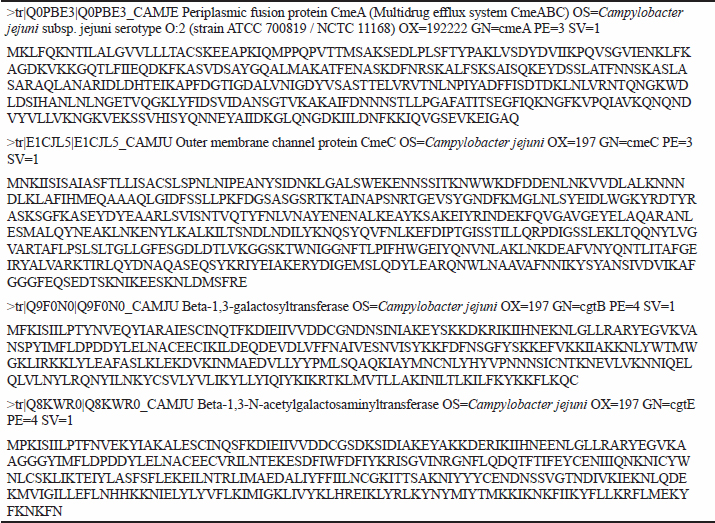

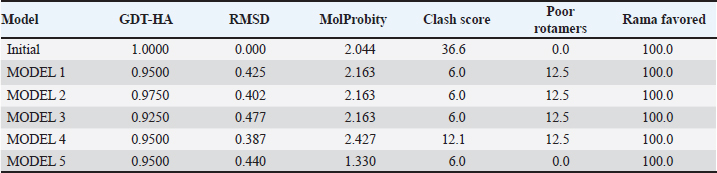

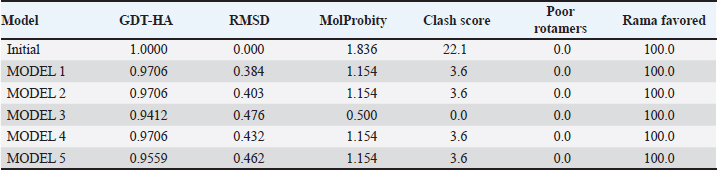

Campylobacter jejuni protein sequences retrieval and structure predictionThe amino acid sequences of the CmeABC efflux pump components (periplasmic fusion protein cmeABC, UniProt ID: Q0PBE3; outer membrane channel protein cmeC, UniProt ID: E1CJL5) and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis enzymes (CgtB, UniProt ID: Q9F0N0; acetylgalactosaminyltransferase CgtE, UniProt ID: Q8KWR0) from C. jejuni were retrieved (Table S1) from the UniProt database. A homology model of the target protein was constructed and refined using the Galaxy web server. The validation was performed using Saves v6.1 (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). Computational modeling of protein-peptide bindingTo understand how ginger-derived peptides might interact with the target enzyme, we used the computational tool of HDOCK (http://hdock.phys.hust. edu.cn/). HDOCK uses a combination of pre-existing examples and free-form searching to predict how these peptides might bind to the target enzyme (Yan et al., 2017). By incorporating known biological information, HDOCK scores different binding possibilities and identifies the most likely interaction (Yan et al., 2020). Chimera × 1.9 software was used to visualize the interactions between proteins and peptides. Ethical approvalNot needed for this study. ResultsPeptides are predicted for AMP activity and nonallergenicityAnalysis of Z. officinale-derived peptides revealed varying degrees of predicted AMP activity and allergenicity. Peptides with ID numbers A0A166IYH9 and A0A286QYA5 have high predicted AMP scores. Crucially, both peptides are predicted to be nonallergens (Table 2). Physicochemical properties of the AtpH-1 and AtpH-2 peptidesIn silico analysis revealed that AtpH-1 (1104.36 g/mol) and AtpH-2 (1820.25 g/mol) molecular weights have a theoretical pI of 5.52, suggesting a slight negative charge at physiological pH; AtpH-2 exhibited a higher extinction coefficient (1,490), suggesting more aromatic amino acids; AtpH-2 also demonstrated greater stability with a longer estimated half-life (>10 hours in vitro), a lower instability index (14.05), a higher aliphatic index (183.53), and a slightly higher GRAVY score (2.147), respectively, indicating increased thermostability and hydrophobicity compared to AtpH-1 (Table 3). Structure prediction, refinement, and validation of Z. officinale peptidesTo better understand the structures of the two selected peptides, homology modeling was performed. This process revealed distinct structural differences between the two peptides [Fig. 1. Following the initial modeling stage, the top-ranked refined models generated by the Galaxy web server (detailed in Table S2.) underwent more checks]. The top-ranked models were further refined using PEP-FOLD (Fig. S1). This refinement was performed to ensure the quality of the targeted models. The resulting average global distance test scores, inversely proportional to the root mean square deviation (RMSD) and thus indicative of model accuracy, were 0.788 for AtpH-1 and 0.627 for AtpH-2. To confirm the quality of the refined models, Discovery Studio software version 21.1.0.20298 was used. The Ramachandran plot analysis revealed that the amino acids in the modeled peptides were primarily located in the allowed alpha-helix regions (Fig. 1, lower panel). Table 2. Allergenicity and AMP activity of Zingiber officinale-derived peptides.

Table 3. Physicochemical properties of Zingiber officinale-derived proteins.

Fig. 1. Predicted 3D structures and Ramachandran plots of the AtpH-1 and AtpH-2 peptides from Zingiber officinale. Top panels: (A): Homology-modeled and refined 3D structures of AtpH-1; (B): Homology-modeled and refined 3D structures of AtpH-2. Bottom panel: Ramachandran plots for AtpH-1 (left) and AtpH-2 (right) generated by Discovery Studio. The plots indicate the distribution of amino acid residues, with all residues located within the allowed alpha-helix regions. Phi: angle between the alpha carbon atom and the carbonyl carbon atom of the amino acid residue. Psi: angle between the alpha carbon atom and the nitrogen atom of the next amino acid residue. Table 4. Structural modeling and characterization of the efflux pump and LOS proteins form Campylobacter jejuni.

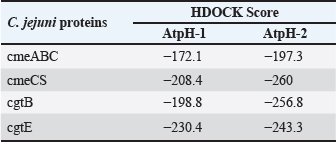

Computational prediction of C. jejuni protein structureStructural modeling of the C. jejuni efflux pump and LOS proteins (cmeABC, cmeC, a likely obsolete protein, and a glycosyltransferase) using AlphaFold v2 and X-ray crystallography revealed high-quality models of GMQE, indicating reliable structural predictions (Table 4 and Fig. S2. The initial modeling and refinement were performed using the Galaxy web server (Fig. 2 and Table S3), and the top models were further validated using SAVES v6.1 and Ramachandran plot analysis. This analysis showed that over 94% of the residues in each modeled peptide (cmeABC, cmeC, cgtB, and cgtE) were located in favored regions (95.8%, 95.9%, 94.8%, and 96.1%, respectively) (Fig. 3). Protein–peptide docking interactionsComputational modeling using the latest version of the HDOCK server was used to predict how peptides interact with and inhibit efflux pumps and LOS in C. jejuni. Table 5, Figures 4 and 5 present the predicted interactions between two ginger-derived peptides (AtpH-1 and AtpH-2) and several proteins from C. jejuni, as determined by HDOCK docking simulations (lower i.e., more negative, HDOCK scores indicate stronger predicted binding). AtpH-2 consistently demonstrated stronger predicted binding to all targeted C. jejuni proteins than AtpH-1.

Fig. 2. The predicted 3D structures of efflux pumps and LOS proteins from Campylobacter jejuni. (A): CmeABC; (B): CmeC; (C): CgtB; (D): beta-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (CgtE) are represented as ribbons.

Fig. 3. Analysis of the structural quality of several Campylobacter jejuni proteins involved in efflux pumps and LOS production: Ramachandran plots to assess the different shapes and angles that these proteins can adopt. Each plot (A, B, C, and D) corresponds to a specific protein: CmeABC, CmeC, CgtB, and beta-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (CgtE), respectively. DiscussionCampylobacteriosis is mainly caused by the zoonotic pathogen C. jejuni, and it poses a significant threat to human health. Furthermore, it is the most often documented bacterial cause of diarrheal sickness in many affluent nations (Souza et al., 2018), and it is primarily caused by eating raw or undercooked poultry. Other transmission methods include contaminated milk and water (Igwaran and Okoh, 2020), although infections are usually sporadic, with rare outbreaks reported (Blaser and Engberg, 2018). Campylobacter is commonly found in the intestinal tracts of poultry. Improper handling of raw poultry during food preparation can also lead to cross-contamination of other foods and surfaces (Farmer et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2019), highlighting the need for effective control strategies. Table 5. Analysis of the docking of Campylobacter jejuni proteins with Zingiber officinale-derived peptides.

Ginger contains approximately 9% protein alongside other macronutrients like carbohydrates and lipids (Mahboubi, 2019; Sangwan et al., 2014). Although not a primary protein source, ginger-derived protein and its content contribute to its overall nutritional profile and potential health benefits. The peptides and other bioactive compounds in it offer a range of potential health benefits for both humans and broiler chickens, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and digestive health-promoting effects (Khan et al., 2012; Siddiqui et al., 2024). While ginger is recognized for various health benefits, characterizing the ginger-derived peptide profile for possible anti-Campylobacter properties could be pivotal given the importance of campylobacteriosis to public health and the demand for innovative control methods. Beyond the protein content, Z. officinale contains a diverse array of bioactive compounds, including gingerols (such as 6-gingerol), shogaol (like 6-shogaol), zingerone, and various essential oils (containing components like zingiberene and β-sesquiphellandrene), which are known to possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties (Mao et al., 2024). These compounds could synergistically or independently contribute to the overall anti-Campylobacter activity observed or predicted. Our computational approach aimed to bridge this gap by screening short ginger-derived protein sequences for potential bioactivity.

Fig. 4. Protein-peptide binding models: Predicted 3D structures of AtpH-1 and AtpH-2 bound to efflux pumps and of Campylobacter jejuni proteins. (A): molecular complex of cmeABC (green) and AtpH-1 (yellow); (B): molecular complex of cmeABC protein (green) and AtpH-2 (yellow); (C): molecular complex of cmeC and AtpH-1 (yellow); (D): molecular complex of Beta-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (cmeC) and AtpH-2 (yellow).

Fig. 5. Protein-peptide binding models: Predicted 3D structure of AtpH-1 and AtpH-2 bound to LOS of Campylobacter jejuni proteins. (A): molecular complex of cgtB (green) and AtpH-1 (yellow); (B): molecular complex of cgtB protein (green) and AtpH-2 (yellow); (C): molecular complex of Beta-1,3-galactosyltransferase (cgtE) (green) and AtpH-1 (yellow); (D): molecular complex of cgtE (green) and AtpH-2 (yellow). According to previous research by Fjell et al. (2011), the natural biological activity of a peptide is influenced by its electrical charge, molecular weight, hydrophobicity, and other properties. Various physicochemical characteristics may explain the improved stability and enhanced anti-Campylobacter activity observed in ginger-derived peptides. Disruption of microbial membranes by aromatic amino acids (Zhang et al., 2006) combined with increased peptide stability (as evidenced by a longer half-life and lower instability index) is essential for effective and long-lasting antimicrobial action (Nagarajan et al., 2018). Increased hydrophobicity also promotes interaction with bacterial membranes (Chen et al., 2007). Given our aim to identify potential AMPs from Z. officinale, we initiated our search by targeting sequences containing less than 50 amino acids. This is a common size range for AMPs and facilitates focused initial screening of the UniProt database. By prioritizing this size range, we aimed to enrich our dataset for molecules with a higher probability of exhibiting the desired bioactivity before proceeding with further computational analyses. These 27 peptide-like sequences of 50 amino acids are likely derived from various genes within the Z. officinale genome, potentially encoding small proteins or representing processed fragments of larger proteins. In this study, predictive physiochemical analysis of AtpH-1 and AtpH-2 showed a slight negative charge, with AtpH-2 exhibiting a higher extinction coefficient, indicative of a greater abundance of aromatic amino acids, which are known to interact with microbial membranes (Zhang et al., 2006). Although Campylobacter uses several strategies to fight antibiotics, target mutations and drug efflux are especially important for developing resistance to fluoroquinolones and macrolides development. In C. jejuni, the CmeABC efflux pump actively expels a broad range of antimicrobials and toxic compounds, consequently contributing to both intrinsic and acquired resistance to these agents (Luangtongkum et al., 2009). A previous study by Guo et al. (2010) identified and characterized cmeABC homologs in five Campylobacter species (C. jejuni, Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter lari, Campylobacter upsaliensis, and Campylobacter fetus) (Yan et al., 2006). They demonstrated that the CmeABC efflux system is conserved both genetically and functionally across the examined Campylobacter species, emphasizing its significant role in Campylobacter pathogenicity (Guo et al., 2010). Lin et al. (2002) previously demonstrated, through sequence analysis, that cmeC is likely co-transcribed with cmeA and cmeB, indicating coordinated expression, underscoring the essential role of CmeC within the CmeABC efflux pump. Additionally, it was proposed that CmeC contained a crucial part of the CmeABC complex, and functioning in conjunction with CmeA and CmeB in order to facilitate efflux and then contribute to antimicrobial resistance (Lin et al., 2002). Interestingly, understanding ginger-derived peptides, particularly AtpH-1 and AtpH-2, and their interactions with Campylobacter efflux pump suggests a potential mechanism by which this peptide could exert anti-Campylobacter activity, and could allow us to design novel medicines to address the important issue of antibiotic resistance. Further experimental validation is crucial for confirming this interaction and its functional significance. Campylobacter bacteria have a modified outer membrane, that is, instead of the usual LPS, they possess LOS, which is composed of lipid A and core structures, giving Campylobacter a distinct surface structure (Moran, 1997; Duncan et al., 2009). Hameed et al. (2020) suggested that LOS is a key virulence factor in C. jejuni, likely contributing to immune cell stimulation and potentially facilitating binding to various cell types due to its abundance on the bacterial surface (Hameed et al., 2020). CgtB is a bacterial enzyme involved in carbohydrate synthesis. Ginge-derivedd proteins with antiinflammatory and antimicrobial effects. These proteins may target CgtB, disrupting bacterial function. This presents an intriguing possibility. This disruption can weaken bacterial defenses (LOS). Further research is required to confirm this interaction. As a validated target for antibacterial therapies, the bacterial cell wall plays a dual role: providing structural integrity for bacterial growth and mediating host innate immune responses during infection. The strongest predicted interactions were observed between AtpH-2 and both the component of the efflux pump and LOS biosynthesis enzyme. These findings suggest that these peptides could disrupt bacterial function by interfering with efflux pump activity or LOS production. This could have implications for developing novel antibacterial strategies against C. jejuni, particularly relevant in addressing antibiotic resistance and virulence. ConclusionCampylobacter jejuni represents a considerable public health issue owing to its commonality as a causative agent of diarrheal disease, predominantly spread via infected chicken. Ginger’s various active ingredients, including peptides, such as AtpH-1 and AtpH-2, show potential for targeting crucial bacterial components such as the CmeABC efflux pump in C. jejuni, and disrupting this efflux pump could compromise bacterial defenses and enhance the efficacy of existing or future antimicrobial agents. The surface LOS of Campylobacter is susceptible to disruption and inhibition by plant-derived peptides. AtpH-2 may synergistically weaken bacterial defenses by inhibiting the LOS biosynthesis enzymes CgtB and CgtE, in addition to its other potential mechanisms of action. Further investigation into the specific mechanisms of action and the interaction between ginger-derived peptides and Campylobacter is crucial. AcknowledgmentsN/A. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. FundingN/A. Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, writing –original draft, Writing –review & editing, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Data availabilityData are contained within the article and the Supplementary Materials. ReferencesAjayi, O.B., Akomolafe, S.F. and Akinyemi, F.T. 2013. Food value of two varieties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) commonly consumed in Nigeria. ISRN Nutr. 2013, 359727. Blaser, M. and Engberg, J. 2018. Clinical aspects of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli infections, in Campylobacter. In Campylobacter, 3rd ed. Eds., Nachamkin, I., Szymanski, C.M. and Blaser, M.J. Washington, DC: ASM Press, pp: 99–121. Brunner, K., John, C.M., Phillips, N.J., Alber, D.G., Gemmell, M.R., Hansen, R., Nielsen, H.L., Hold, G.L., Bajaj-Elliott, M. and Jarvis, G.A. 2018. Novel Campylobacter concisus lipooligosaccharide is a determinant of inflammatory potential and virulence. J. Lipid Res. 59, 1893–1905. Burnham P.M. and Hendrixson D.R. 2018. Campylobacter jejuni: collective components promoting a successful enteric lifestyle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 551–565. Chen, Y., Guarnieri, M.T., Vasil, A.I., Vasil, M.L., Mant, C.T. and Hodges, R.S. 2007. Role of peptide hydrophobicity in the mechanism of action of alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1398–1406. Dahab, M. and Aladhadh, M. 2025. Bioinformatics exploration of identified garlic-derived antimicrobial peptides: a food-based approach to quorum sensing inhibition in foodborne pathogens. Boll. Soc. Ital. Biol. Sper. 98, 13130; doi:10.4081/jbr.2025.13130. Dimitrov, I., Bangov, I., Flower, D.R. and Doytchinova, I. 2014. Doytchinova, AllerTOP v.2–a server for in silico prediction of allergens. J. Molecul. Model. 20, 2278. Duncan, J.A., Gao, X., Huang, M.T.H., O’Connor, B.P., Thomas, C.E., Willingham, S.B., Bergstralh, D.T., Jarvis, G.A., Sparling, P.F. and Ting, J.P.Y. 2009. Neisseria gonorrhoeae activates the proteinase cathepsin b to mediate the signaling activities of the NLRP3 and ASC containing onflammasome. J. Immunol. 182, 6460–6469. Farmer, S., Keenan, A. and Vivancos, R. 2012. Food- borne Campylobacter outbreak in liverpool associated with cross-contamination from chicken liver parfait: implications for investigation of similar outbreaks. Public Health 126, 657–659. Fjell, C.D., Hiss, J.A., Hancock, R.E. and Schneider, G. 2011. Designing antimicrobial peptides: form follows function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 37–51. Germoush, M.O., Fouda, M., Mantargi, M.J., Sarhan, M., Alrashdi, B.M., Massoud, D., Alzwain, S., Ghaboura, N., Altyar, A.E. and Abdel-Daim, M.M. 2024. Molecular docking of eleven snake venom peptides targeting human immunodeficiency virus capsid glycoprotein as inhibitors. Open Vet. J. 14, 2936–2949. Grontved, A. and Pittler, M.H. 2013. Ginger root against sickness. A controlled trial on the open sea. Br. J. Anaesth. 84, 367–371. Guillaume, G., Ledent, V., Moens, W. and Collard, J.M. 2004. Phylogeny of efflux-mediated tetracycline resistance genes and related proteins revisited. Microb. Drug Resist. 10, 11–26. Guo, B., Lin. J., Reynolds. D.L. and Zhang. Q. 2010. Contribution of the multidrug efflux transporter CmeABC to antibiotic resistance in different Campylobacter species. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7, 77–83. Guo, B., Wang, Y., Shi, F., Barton, Y.W., Plummer, P., Reynolds, D.L., Nettleton, D., Grinnage-Pulley, T., Lin, J. and Zhang, Q. 2008. CmeR functions as a pleiotropic regulator and is required for optimal colonization of Campylobacter jejuni in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1879–1890. Hameed, A., Woodacre, A., Machado, L.R. and Marsden, G.L. 2020. An updated classification system and review of the lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis gene locus in Campylobacter jejuni. Front. Microbiol. 11, 677. Igwaran,A. and Okoh,A.I. 2020. Molecular determination of genetic diversity among Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from milk, water, and meat samples using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (ERIC-PCR). Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 10, 1830701. Kaakoush, N.O., Castano-Rodriguez, N., Mitchell, H.M. and Man, S.M. 2015. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 687–720. Kang, C.R., Bang, J.H. and Cho, S.I. 2019. Campylobacter jejuni foodborne infection associated with cross-contamination: outbreak in Seoul in 2017. Infect. Chemother. 51, 21–27. Karlyshev, A.V., Champion, O.L., Churcher, C., Brisson, J.R., Jarrell, H.C., Gilbert, M., Brochu, D., St Michael, F., Li, J., Wakarchuk, W.W. and Goodhead, I. 2005. Analysis of Campylobacter jejuni capsular loci reveals multiple mechanisms for the generation of structural diversity and the ability to form complex heptoses. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 90–103. Khan, R., Naz, S., Nikousefat, Z., Tufarelli, V., Javdani, M., Qureshi, M. and Laudadio, V. 2012. Potential applications of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in poultry diets. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 68, 245–252. Lin, J., Akiba, M., Sahin, O. and Zhang, Q. 2005. CmeR functions as a transcriptional repressor for the multidrug efflux pump CmeABC in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 1067–1075. Lin, J., Michel, L. and Zhang, Q. 2002. CmeABC functions as a multi drug efflux system in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 2124–2131. Luangtongkum, T., Jeon, B., Han, J., Plummer, P., Logue, C.M. and Zhang, Q. 2009. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission, and persistence. Future Microbiol. 4, 189–200. Mao, Q.Q., Xu, X.Y., Cao, S.Y., Gan, R.Y., Corke, H., Beta, T. and Li, H.B. 2019. Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 8, 185. Mahboubi, M. 2019. Zingiber officinale Rosc. essential oil, a review on its composition and bioactivity. Clin. Phytosci. 5, 12. Moran,A.P. 1997. Structure and conserved characteristics of Campylobacter jejuni lipopolysaccharides. J. Infect. Dis. 176, S115–S121. Nagarajan, D., Nagarajan, T., Roy, N., Kulkarni, O., Ravichandran, S., Mishra, M., Chakravortty, D. and Chandra, N. 2018. Computational antimicrobial peptide design and evaluation against multidrug- resistant clinical isolates of bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 3492–3509. Nawrot, R., Barylski, J., Nowicki, G., Broniarczyk, J., Buchwald, W. and Goździcka-Józefiak, A. 2014. Plant antimicrobial peptides. Folia. Microbiol (Praha). 59, 181–196. Nikaido, H. and Pagès, J.-M. 2012. Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 340–363. Nyati, K.K. and Nyati, R. 2013. Role of Campylobacter jejuni infection in the pathogenesis of Guillain– Barré syndrome: an update. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 852195. Opara, E.I. and Chohan, M. 2014. Culinary herbs and spices: their bioactive properties, the contribution of polyphenols and the challenges in deducing their true health benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 19183– 19202. Parkhill, J., Wren, B.W., Mungall, K., Ketley, J.M., Churcher, C., Basham, D., Chillingworth, T., Davies, R.M., Feltwell, T., Holroyd, S. and Jagels, K. 2000. The genome sequence of the food borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403, 665–668. Piddock, L.J. 2006. Clinically relevant chromosomally encoded multi drug resistance efflux pumps in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 382–402. Poole, K. 2005. Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56, 20–51. Sangwan, A., Kawatra, A. and Sehgal, S. 2014. Nutritional composition of ginger powder prepared using various drying methods. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 2260–2262. Siddiqui, I., Owais, M. and Husain, Q. 2024. Antimicrobial effects of peptides from fenugreek and ginger proteins using Fe3O4 [at] PDA-MWCNT conjugated trypsin by improving enzyme stability & applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 282(Pt 5), 137197. Souza, C.O., Vieira, M.A., Batista, F.M., Eulalio, K.D., Neves, J.M., Sá, L.C., Monteiro, L.C., Almeida-Neto, W.S., Azevedo, R.S., Costa, D.L. and Cruz, A.C. 2018. Serological markers of recent Campylobacter jejuni infection in patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome in the State of Piauí, Brazil, 2014-2016. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98, 586–588. St Michael, F., Szymanski, C.M., Li, J., Chan, K.H., Khieu, N.H., Larocque, S., Wakarchuk, W.W., Brisson, J.R. and Monteiro, M.A. 2002. The structures of the lipooligosaccharide and capsule polysaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni genome sequenced strain NCTC 11168. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5119–5136. Talukdar, P.K., Turner, K.L., Crockett, T.M., Lu, X., Morris, C.F. and Konkel, M.E. 2021. Inhibitory effect of puroindoline peptides on Campylobacter jejuni growth and biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 12, 702762. Tegtmeyer, N., Sharafutdinov, I., Harrer, A., Soltan Esmaeili, D., Linz, B. and Backert, S. 2012. Campylobacter virulence factors and molecular host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 431, 169–202. Wagle, B.R., Donoghue, A.M. and Jesudhasan, P.R. 2021. Select phytochemicals reduce Campylobacter jejuni in postharvest poultry and modulate the virulence attributes of C. Jejuni. Front. Microbiol. 12, 725087. Wilkins, M.R., Gasteiger, E., Bairoch, A., Sanchez, J.C., Williams, K.L., Appel, R.D. and Hochstrasser, D.F. 1999. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 112, 531–552. Yan, M., Sahin, O., Lin, J. and Zhang, Q. 2006. Role of the CmeABC efflux pump in the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter under selection pressure. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58, 1154–1159. Yan, Y., Tao, H., He, J. and Huang, S.Y. 2020. The HDOCK server for integrated protein–protein docking. Nat. Protoc. 15, 1829–1852. Yan, Y., Zhang, D., Zhou, P., Li, B. and Huang, S.Y. 2017. HDOCK: a web server for protein-protein and protein-DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(W1), W365–W373. Zhang, L., Tian, X., Sun, L., Mi, K., Wang, R., Gong, F. and Huang, L. 2024. Bacterial efflux pump inhibitors reduce antibiotic resistance. Pharmaceutics 16, 170. Zhang, L., Tian, X., Sun, L., Mi, K., Wang, R., Gong, F. and Huang, L. 2024. Bacterial efflux pump inhibitors reduce antibiotic resistance. Pharmaceutics 16, 170. Zhang, W., Sato, T. and Smith, S.O. 2006. NMR spectroscopy of basic/aromatic amino acid clusters in membrane proteins. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 48, 183–99. Supplementary materials S1

Fig. S1 Predicted secondary structure profiles of and peptides from Zingiber officinale. Using PEP-FOLD web server. (A): AtpH-1; (B): AtpH-2. A color-coded representation to visualize structural propensities. Red indicates helical (alpha-helix), green represents extended (beta-strand/sheet), and blue signifies coil (turns/loops) conformations.

Figure S2. Structural modeling of Campylobacter jejuni efflux pump and LoS proteins. A stereochemical quality of protein structures generated using Swiss Expasy web server. (A): CmeABC; (B): CmeC; (C): CgtB; (D): beta-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (CgtE).

Table S1. A total of four protein amino acid sequences from Zingiber officinale-retrieved from the UniProt.

Table S2. Refinement Zingiber officinale-derived peptides structure using GalaxyRefine. A: AtpH-1 protein.

A: AtpH-2 protein.

Table S3. The quality of a refined protein structure. AtpH-1 peptide

AtpH-2 peptide | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 Web Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=240109 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 Harvard Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi (2025) Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 Turabian Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. 2025. Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 Chicago Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. "Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi. "Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2457-2470. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Maryam Saleh Alhumaidi (2025) Computational modeling approach to identify potential anti-Campylobacter peptides from Zingiber officinale targeting efflux pump and lipooligosaccharide. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2457-2470. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.18 |