| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3193-3205 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(7): 3193-3205 Research Article Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settingsSoad Eid1*, Sonia A. Rizk1, Dalia Ayman2, Mahmoud Ali2, Mohamed Saad1, Ahmed A. El-Sanousi3, Ausama A. Yousif3 and Mohamed A. Shalaby31Veterinary Serum and Vaccine Research Institute, Agriculture Research Center, Giza, Egypt 2Egyptian Company for Biological & Pharmaceutical Industries (Vaccine Valley), Giza, Egypt 3Department of Virology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt *Corresponding Author: Soad Eid. Veterinary Serum and Vaccine Research Institute, Agriculture Research Center, Giza, Egypt. Email: soadeid.se [at] gmail.com Submitted: 10/06/2025 Revised: 23/06/2025 Accepted: 23/06/2025 Published: 31/07/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

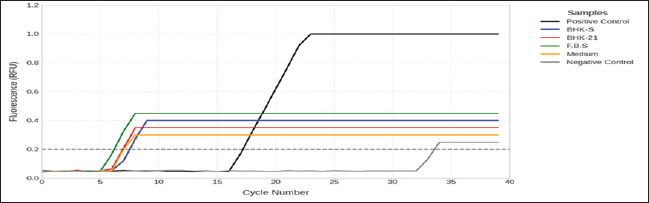

ABSTRACTBackground: The foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) remains a significant threat to livestock health and agricultural economies, particularly in endemic regions such as Egypt. Although suspension cultures of baby hamster kidney (BHK)-21 cells are widely used for FMD vaccine production. Suspension cells play a vital role in biomanufacturing, but their high cost often limits their accessibility. This straightforward method offers an efficient and economical solution for obtaining BHK-adapted suspension cells that are ideal for large-scale cultivation in bioreactors. Aim: We developed a simplified and cost-effective method for adapting BHK-21 cells to suspension culture using a progressive accelerated rolling system, eliminating the need for microcarriers or complex bioreactor systems. The resulting suspension-adapted cells (BHK-S) were assessed for growth kinetics, sterility, postthaw viability, and their ability to support FMDV replication and 146S antigen production. Methods: Conversion of adherent BHK-21 to BHK suspension was performed, followed by investigation of cell counts, cell viability, cell morphology, and growth curve analysis. Results: BHK-S cells demonstrated robust growth with >95% viability and a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml. After FMDV infection, suspension cultures yielded significantly higher virus titers (>108 TCID50/ml) compared with adherent cultures (106.8 TCID50/ml; p < 0.001). Furthermore, 146S antigen yield was substantially improved, with suspension cultures producing 4.4 µg/ml compared to 1.5 µg/ml in adherent cells. Scale-up to a 10L bioreactor confirmed the stability of growth parameters and viral productivity. Conclusion: This streamlined and scalable approach for adapting BHK-21 cells to suspension culture offers a practical and affordable alternative for FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings, facilitating the transition from bench-to-bioprocessing scale. Keywords: Foot and mouth disease virus, Baby Hamster kidney cells, Suspension culture, 146S antigen, Bioreactor scalability. IntroductionFoot-and-mouth disease (FMD) is a highly contagious viral disease caused by the FMD virus (FMDV), and it poses a significant threat to the livestock industry in Egypt and neighboring regions (El-Shehawy et al., 2022; Kandeil et al., 2023). The disease results in substantial economic losses, primarily due to trade restrictions imposed on endemic areas (Knight-Jones and Rushton, 2013). Over the past decade, FMDV serotypes O, A, and SAT2 have been detected in both domestic and wild animals, highlighting their widespread prevalence (Yousef et al., 2025). FMD affects nearly all cloven-hoofed domestic and wild animals globally, presenting with clinical signs such as fever, lameness, and vesicular lesions on the feet and tongue (Grubman and Baxt, 2004). The causative agent, FMDV, is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus of the Picornaviridae family, characterized by seven antigenically distinct serotypes (O, A, C, Asia1, SAT1, SAT2, and SAT3) and numerous evolving subtypes generated through recombination and error-prone replication (Mason et al., 2003; Domingo et al., 2012). In Egypt, FMDV vaccine manufacturing faces multifaceted challenges that significantly impact disease control efforts. The national demand of approximately 25–30 million vaccine doses annually substantially exceeds the current production capacity of 18–20 million doses (Kappes et al., 2023). This shortfall is exacerbated by technical limitations in traditional adherent cell culture systems, including space constraints, labor-intensive processes, and scalability issues (Genzel, 2015; Aunins, 2020). Furthermore, the cocirculation of multiple FMDV serotypes (O, A, and SAT2) necessitates continuous vaccine strain updates (Kandeil et al., 2023), while maintaining consistent antigen yields remains challenging (Paton et al., 2009). The situation is further complicated by infrastructure constraints, cold chain maintenance difficulties, and quality control challenges that affect vaccine potency and stability (Krause et al., 2021). These limitations, coupled with the economic burden of production costs and regulatory requirements, underscore the urgent need for innovative approaches to vaccine manufacturing technology (Genzel and Reichl, 2021). The transition to suspension culture systems presents a promising solution to address these challenges, potentially offering enhanced scalability, improved process control, and increased production efficiency (Kumar et al., 2020. Vaccination remains the cornerstone strategy for controlling FMD in endemic regions, with Egypt administering approximately 18 million vaccine doses annually (Hegazy et al., 2021; El-Tholoth and El-Kenawy, 2022). Current vaccine production relies on inactivated whole FMDV propagated in baby hamster kidney (BHK)-21 cell cultures, although adaptation of field strains to cell culture systems often presents significant challenges, including suboptimal virus yields and antigenic mismatches between vaccine and field strains (Kotecha et al., 2016; Mahapatra and Parida, 2018). The development of efficient cell culture systems for FMDV propagation has evolved significantly since the pioneering work of Mowat and Chapman (1962), who demonstrated BHK-21 clone 13’s susceptibility to FMDV infection. Subsequent breakthroughs by Capstick et al. (1962) achieved the successful adaptation of BHK-21 cells for suspension growth, while Telling and Elsworth (1965) advanced this technology to large-scale bioreactor production using serum-containing media, establishing the foundation for modern vaccine manufacturing processes (Pay and Hingley, 1987; Doel, 2003). The adaptation of cell cultures for anchorage-independent growth has revolutionized bioprocessing, particularly in viral vaccine production (Butler et al., 2020; Genzel and Reichl, 2021). BHK cells, which are widely utilized in FMDV vaccine manufacturing, traditionally rely on anchorage-dependent systems that pose significant limitations in terms of scalability, process efficiency, and cost-effectiveness (Kumar et al., 2020. The transition to anchorage-independent growth in suspension cultures addresses these challenges while enabling seamless scale-up in bioreactors (Kallel et al., 2019; Hema et al., 2021). This advancement has particularly enhanced the production capacity and economic viability of FMDV vaccine manufacturing processes (Capstick et al., 1962). This study focused on the adaptation of BHK cells for anchorage-independent growth and the subsequent evaluation of their performance in the bioreactor-scale production of FMDV. We developed suspension-adapted BHK-21 (BHK-S) cells and characterized their growth characteristics as a preparatory step for establishing master seed cell and working seed cell banks. BHK-S cells were evaluated for their ability to achieve high cell densities in growth media and adhesive properties. The 146S antigen is the most potent immunogen in FMD vaccines; thus, its concentration was quantified in both suspension and adherent cultures. Additionally, the infectivity of FMDV in both culture types was assessed. This cell-culture-based FMDV production technology provides a rapid, cost-effective, and scalable platform for developing vaccines against newly emerging FMDV strains, making it an ideal solution for developing countries with limited resources. Materials and MethodsCell lines, cell culture media, and FMDVThe BHK-21 adherent cell line, obtained from The Pirbright Institute (UK), was utilized at passage 23 and is currently maintained at the Foot-and-Mouth Disease Department, Veterinary Serum and Vaccine Research Institute, Egypt. We grew the seeds in T-75 flasks at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (earl’s salt) (DMEM; caisson, Grand, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowest, USA), and cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/cm2. A medium supplemented with essential amino acids (NEAA100X, Sigma Aldrich) and vitamins for cell culture (50×) (Sigma Aldrich) was used to increase the growth of BHK-S during the adaptation period, and an anti-clumping agent was used to prevent the formation of cell aggregates (pluronic acids, Sigma Aldrich) (Hema et al., 2021). FMDV (O/EGY/sharkia/1972) (Manisa lineage strain) was propagated in BHK-21 adherent cells, harvested at 80% CPE, and stored at − 80°C. The initial virus stock had a titer of 106.5 TCID50/ml. Conversion of adherent BHK-21 to BHK suspensionSuspension gradual adaptation of adherent BHK-21 cells for maintenance of a BHK-21 suspension (BHK-S) culture took approximately 2 months. Adherent BHK-21 cells were directly adapted to minimum essential medium (Hank’s) (Caisson, USA) containing 8% v/v FBS, and L-glutamine, in smooth roller flasks (Greiner, 850 cm2, France). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a roller system (with increasing speed from 4.5 rotations/min (rpm) that increased until 7.5 rotations/minute), and the FBS was progressively eliminated during the weaning procedure. Adaptation was considered successful when cells maintained 95% viability over three consecutive passages (Park et al., 2021). Once the cells had adapted to grow in suspension, the resulting BHK-S cells were serially passaged every 1 or 2 days until they showed stable growth. The suspension-adapted cells were cryopreserved at every passage from the first passage until the 10th passage. Microscopic examination of each passageA sample from each passage of the suspended cells, and cells was microscopically examined using an inverted microscope (Olympus) via a 40× magnification lens. Cell counting and percentage viability percentage at every passage of the weaning stepThe cell culture mixture was diluted and passaged every 2 or 3 days. The viable cell density (VCD) and viability were measured via trypan blue staining using an automatic cell counter analyzer (Bio-RAD®, TC20 automated cell count). A sample of 10 μl of suspended cells was mixed with an equal volume of 0.4% trypan blue stain 0.85% NaCl (Lonza®),10 μl of the stained suspended cells was added to a disposable glass slide for automated cell counting, and then the average cell count reading of three samples was taken for characterization of the BHK-S cells (Strober, 2001). ViabilityApproximately 50 µl of cell suspension will be diluted with DMEM, and the cells will be counted with a hemocytometer to assess cell viability (Strober, 2015). Cell morphologyThe selected clone cells in the culture media were morphologically examined in terms of shape and arrangement using an inverted microscope daily (Abercrombie, 1978). Doubling time (growth curve analysis)To calculate the cell doubling time, flasks were separately sampled twice (16, 24, and 48 hours), and counting was performed when the cells were in the logarithmic phase on the basis of the highest number of cells counted twice the counting interval (DeliveReD, 2012). Growth curve analyses were performed in duplicate, twice individually, with a seeding density of 0.6×106 cells/ml. The VCD and percent viability were measured. Cell-specific calculations were performed according to the following equations: Specific growth rate: μ (h-1)

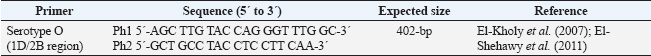

X: VCD (per ml); t: time points of sampling (hour); n and n-1: two consecutive sampling points. Sterility testThe cell seeds will be investigated in a specific culture medium (Thioglycolate, Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA), and Brain Heart Infusion Broth) in terms of microbial and mycotic contamination at a specified time (Nema and Khare, 2012). A mycoplasma test using a real-time PCR kit [Mycoplasma 16S ribosomal RNA gene (genesig® standard kit)] revealed that the cells, medium, and FBS were free from mycoplasma. Cryopreservation of BHK-S cells after every passageA total of 10 ml of adapted BHK-S cells was added to a Falcon tube (15 ml, Greiner®) and centrifuged (cooling centrifuge, BioBase®) at 300 × g for 10 minutes. The cells were pelleted, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in freezing medium containing 90% F.B.S. and 10% DMSO. The mixture was then aliquoted into a myotube and preserved in a Mr. Frosty ® freezer at −80°C; after 24 hours, the myotubes with frozen cells were transferred to a liquid nitrogen tank (−196°C). The cryopreserved cells were subsequently revived and transferred to a shaker flask containing growth medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. A sample of growing suspended cells was taken for the calculation of viability and VCD. Propagation and titration of FMDVThe FMDV vaccine strain O/Egypt/sharqia/72 (manisa lineage strain) was obtained from the Animal Health and Research Institute, Egypt, 2021 (VV). Both adherent BHK-S cells and BHK-S cells at every passage were infected with FMDV O/Egypt/sharqia/72 (manisa lineage strain) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001. The supernatants from infected cultures of BHK-S will be harvested at 16, 20, or 24 hours post-infection (hpi). VCD of infected BHK-S and FMDV infectivity titrationFMDV titers harvested from every passage of BHK-S and adherent BHK were determined via endpoint titration using the Spearman–Kärber calculation and expressed as the tissue culture infective dose affecting 50% of the cultures (TCID50) per ml (Lei et al., 2021). Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Confirmation of virus propagation and titration via PCRViral RNA extraction and RT-PCRVirus harvested from every passage (200 µl) was extracted via RNA extraction using the Easypure® Viral DNA/RNA Kit (Transgene, Cat No ER201-01) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples, the positive control (initial virus stock), and the negative control were then subjected to one-step RT-PCR via COSMO RT-PCR master mix (Willow fort, Cat NO. WF10204002) with the specific primer Serotype O (1D/2B region) as its sequence shown in Table 1. The reaction was subjected to one cycle of 95°C for 5 minutes followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds and 46°C for the Serotype O primers, followed by 72°C for 1 minute, and finally, one cycle of 72°C for 10 minute as the final extension cycle (Table 1). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, followed by ethidium bromide staining and visualization with a UV Trans-illuminator (El-Kholy et al., 2007; El-Shehawy et al., 2011). Scaling up to a bioreactor volume of 10 mlA scale-up study was performed using stirred glass tank bioreactors. Briefly, a 10-l volume bioreactor (Eppendorf®) was filled with 5-l Brescia’s Eagle’s Medium containing (5% NEAA for cell culture, 5% vitamins, and 7% newborn calf serum), which was inoculated. There were 3.57 × 105 live BHK-S cells/ml (27%). The temperature and pH of the bioreactor were controlled at 37°C, and 7.2 ± 0.2, respectively. The dissolved oxygen was controlled through cascade control of the air flow rate (0.1–1.0 vvm). The agitation speed of the impellers was 80 rpm. Sampling every 16, 24, 48 hours for cell count and viability of BHK-S. After 3 days of culture, the BHK-S cells were allowed to settle without agitation for 12 hours, and 80% of the old medium was replaced with fresh medium. After medium exchange, cells were infected with FMDV at an MOI of 0.001, and infected cultures were harvested at 19 hpi for FMDV quantification. Table 1. Shows the sequences of specific primers for the 1D/2B region of FMDV serotype O.

146s quantification of virus harvesting from BHK-S and adherent cellsSucrose gradient preparationLinear sucrose gradients (15%–45% w/v) were prepared in TNE buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA] using a gradient maker. The gradients were prepared fresh and prechilled to 4°C before use. For each gradient, 5.5 ml of 45% sucrose solution and 5.5 ml of 15% sucrose solution were used in the gradient maker to create 11 ml linear gradients in ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman Colter, 14 × 89 mm). Sample preparationThe virus harvest was clarified by low-speed centrifugation (4,024 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C). The supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter to remove cellular debris. A 1 ml sample of the clarified virus suspension was carefully layered onto the pre-formed sucrose gradient. UltracentrifugationThe gradients were centrifuged at 279,500 × g (50,000 rpm) for 2.5 hours at 4°C using a SW41 Ti rotor in a Beckman Colter ultracentrifuge. A blank gradient containing only the TNE buffer was used as a control in each run. Gradient fractionation and analysisAfter ultracentrifugation, the gradients were fractionated from bottom to top using a gradient fractionator (Teledyne ISCO, Lincoln, NE) equipped with a UV monitor. The absorbance of each fraction was continuously monitored at 254 nm. The 146S peak was identified based on its sedimentation characteristics and typically appeared in fractions corresponding to approximately 30% sucrose. Quantification of 146S ParticlesThe concentration of 146S particles was calculated using the following formula:

where:

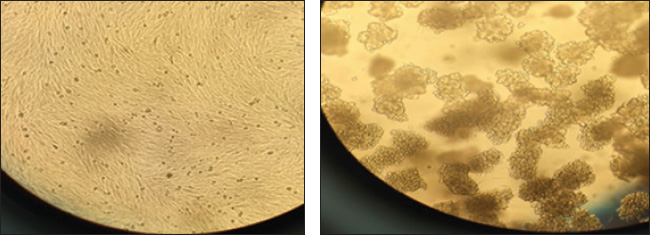

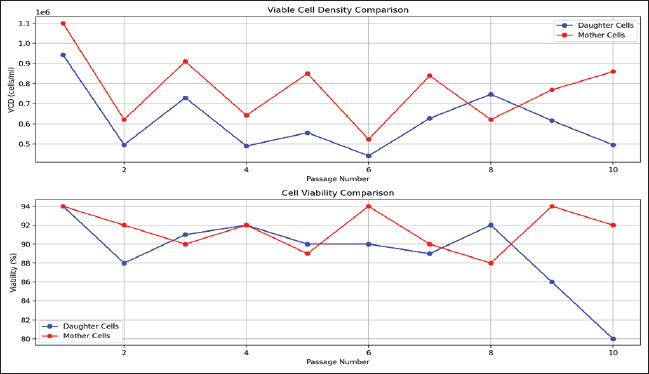

The area under the 146S peak was integrated to determine the total amount of 146S particles. Statistical analysis and visualizationAll statistical analyses were conducted using Python (version 3.×). Descriptive statistics, including mean and SD, were calculated to summarize VCD and viability percentages for both mother and daughter BHK-21 cells. Independent t-tests were performed to compare the means of VCD and viability between the two groups, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between VCD and viability in each group. Data visualization was performed using matplotlib to generate line plots for comparative analysis across passages. Ethical approvalThis study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of Cairo University, Egypt. ResultsGradual adaptation of BHK-adherent to BHK-SBy gradually increasing the speed of the roller system to 4 rpm/min, the cells clumped with each other and aggregated, as shown in Figure 1 so that the anti-clumping agent, such as Pluronic acid, was added to the cell culture medium, and the viable cell count (VCC) and viability % were measured for the mother flask (M) and one daughter flask (D) at every passage of gradual adaptation as follows in Figure 2. Conversion of adherent BHK-21 to BHK suspensionOnce the cells were converted to the suspension state as Figure 3, and the rolling system speed was accelerated that it was reached 10 r.p.m, the static state of the cells made the cells in suspension. The cells aggregated; thus, the anticlumping agent recommended for cell culture must be added to the growth medium to prevent cell aggregation. ViabilityThe cell viability during all the culture passages was estimated to range from 95% to 92%–85%, but in the infected state, the viability decreased to 70%–30% because of the lytic effect of FMDV.

Fig. 1. Gradual adaptation of BHK-adherent cells and other BHK-Ss after a gradual increase in the rolling system speed, as shown by the aggregation and clumping of cells.

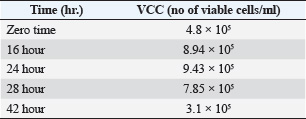

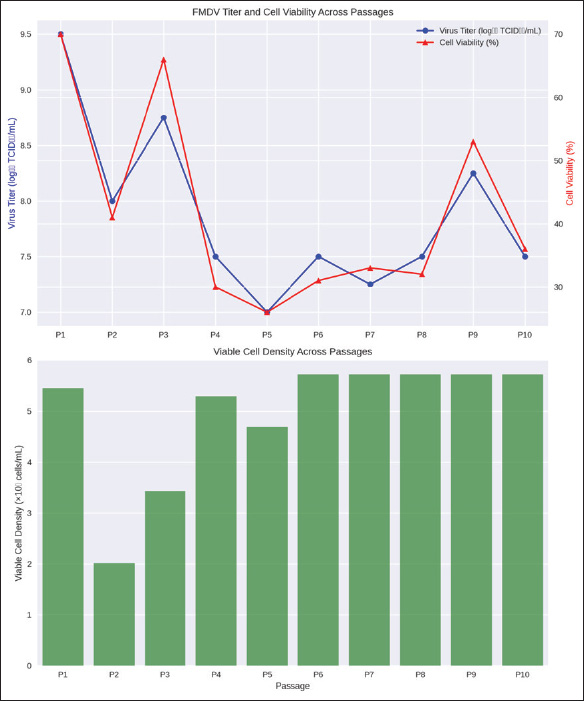

Fig. 2. Two important aspects of cell growth during the suspension adaptation process for both mother and daughter BHK cells: (a) the upper graph illustrates the VCD measured across passages, comparing mother and daughter cells during the transition from adherent to suspension culture. (b) The lower graph displays the cell viability percentage throughout the adaptation process, indicating changes in cell health with successive passages. Cell morphologyA 10 ml sample from a culture adapted to BHK-S was cultured to 25 cm2 T.C. and incubated at 37°C after 4 hours. BHK-S returned to its adherent state and obtained uniform cells, but infected UN-embedded cells were observed due to the high number of ruptured cells caused by the lytic effect of FMDV. Growth analysis (doubling time) of BHK-S cellsMeasuring VCC at different times, 0, 16, 24, 28, and 42 hours, as shown in Table 2. After the calculation, the doubling time was 23.36 hours. The growth kinetics of BHK-21 cells during suspension adaptation, as shown in Fig. 4, were monitored over 42 hours. The initial seeding density was 4.8 × 105 cells/ml, and the cells underwent distinct growth phases throughout the cultivation period. During the lag phase (0–16 hours), cells adapted to the suspension conditions, reaching 8.94 × 105 cells/ml. The exponential growth phase occurred between 16 and 24 hours, during which the cell density increased to a maximum of 9.43 × 105 cells/ml. The specific growth rate (μ) during the exponential phase was 0.0297 hour−¹, corresponding to a doubling time of 23.36 hours. A brief stationary phase was observed around 24–28 hours, followed by a decline phase. During the death phase (28–42 hours), cell viability decreased significantly with a death rate of 0.0664 h−¹, resulting in a final cell density of 3.1 × 105 cells/ml at 42 hours. The growth kinetics demonstrated good correlation with exponential growth modeling (R²=0.9327), indicating consistent cell proliferation during the exponential phase.

Fig. 3. Microscopic examination of BHK cells during adaptation from adherent to suspension culture at different passages, observed under 20× and 40× magnification. The images illustrate morphological changes in the cells as they gradually transition to suspension growth (BHK-S) through successive passages. Table 2. Viable BHK-21 cell counts at different time points during suspension adaptation culture.

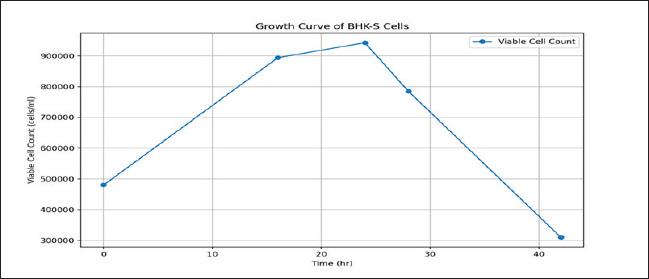

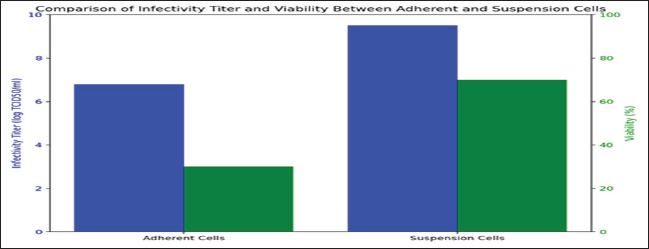

Sterility testSterility tests conducted on cell pellets and media using bacteriological and mycotic media such as BHIB, Thioglycolate, TSB, and TSA confirmed the absence of bacterial or fungal contamination after 14 days of incubation at 35°C. Additionally, real-time PCR analysis revealed that all cell culture components, including BHK-21 and BHK-S cells, tested negative for mycoplasma contamination, ensuring the sterility and integrity of the cell culture system as seen in Figure 5. Cryopreservation of BHK-S cellsPost-thaw viability assessment of cryopreserved BHK-S cells revealed robust recovery characteristics. After 24 hours of culture, the cells exhibited a viability of 90%, with the VCD reaching 0.6 × 105 cells/ml. These results indicate successful preservation of cell functionality and growth potential following the cryopreservation process. Propagation and infectivity of FMDVAdaptation of BHK-21 cells to suspension culture significantly improved FMDV production compared with conventional adherent cultures. The infectivity titration of each FMDV harvest was measured at each passage, together with the VCCs and viability percentages. Although adherent BHK-21 cells achieved a maximum virus titer of 106.8 TCID50/ml, suspension-adapted cells consistently produced higher virus yields across multiple passages, with a mean titer of 7.88 ± 0.73 log 10 TCID50/ml, as illustrated in Figure 6. The highest virus titer (109·5 TCID50/ml) was achieved in passage 1 (P1), coinciding with peak cell viability (70%). Statistical analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between virus titer and cell viability (r=0.967, p < 0.001), particularly evident in early passages. Subsequent passages maintained elevated titers ranging from 107·0 to 108·75 TCID50/ml, representing a consistent 2–3 log increase over adherent culture yields. VCD stabilized at 5.72 × 105 cells/ml in later passages (P6–P10), whereas cell viability fluctuated between 26% and 53%. Notably, a secondary productivity peak occurred at P9 (108·25 TCID50/ml) with 53% cell viability, demonstrating the robustness of the adapted cells for sustained virus production, as in Figure 7. The suspension culture system maintained stable virus production despite varying cell viability (mean: 41.80%), with VCD remaining consistent (mean: 4.95 × 105 cells/ml) throughout later passages. This stability, combined with significantly enhanced virus yields, indicates the successful adaptation of BHK cells for efficient FMDV propagation in suspension culture. These results demonstrate that suspension-adapted BHK cells provide a superior platform for FMDV production, offering both enhanced virus yields and process consistency suitable for industrial-scale vaccine manufacturing.

Fig. 4. Growth curve of BHK-S according to VCC over time.

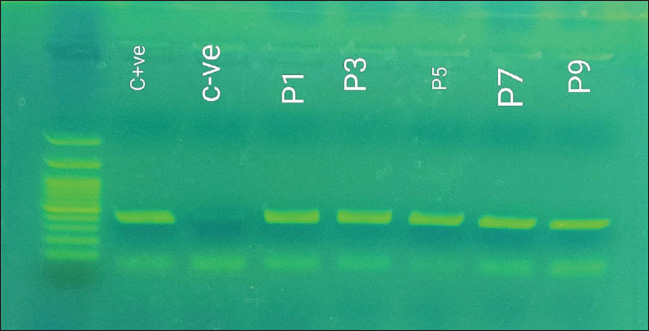

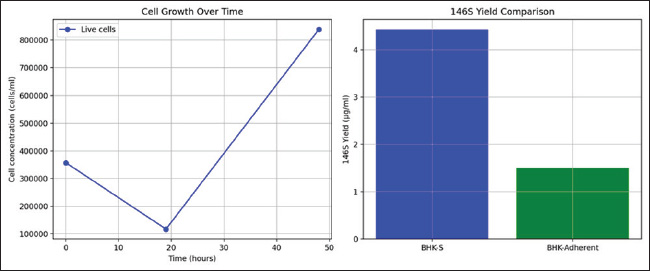

Fig. 5. Mycoplasma detection qPCR results for BHK-21, BHK-S and cell culture components. Confirmation of FMD virus propagation and titration via PCRTo confirm the presence of FMDV in the adapted BHK-S cells, viral RNA was extracted from different cell passages (P1, P3, P5, P7, and P9) and analyzed by PCR using serotype O-specific primers targeting the 1D/2B region. PCR amplification yielded the expected 402-bp product in all tested passages, as visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 8). All samples exhibited clear, single bands of equal intensity, indicating consistent viral replication throughout the adaptation process. The specificity of the amplification was validated by the presence of an identical band in the positive control and the absence of a band in the negative control. These results demonstrate the successful maintenance of FMDV serotype O genetic material during sequential passages of BHK-S cells, confirming the stability of viral propagation in the suspension culture system. Scale up to bioreactorThe scale-up of BHK-S cells to a 10-l bioreactor demonstrated successful cell growth and viral propagation under controlled conditions, and the growth curve of BHK-S cells in the bioreactor is shown in Figure 9. After 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 30% dissolved oxygen, the VCD increased from 3.57 × 105 cells/ml (27% viability) to 8.39 × 105 cells/ml (72% viability). Following 19 hours post-inoculation with FMDV at a MOI of 0.001, the VCC was 1.17 × 105 cells/ml (7% viability), whereas the dead cell count reached 1.56 × 106 cells/ml (93%). These results indicated efficient viral infection and replication, as evidenced by the significant increase in dead cells, which is characteristic of the cytopathic effects induced by FMDV. The bioreactor conditions supported both cell growth and virus production, providing a scalable platform for FMDV antigen generation.

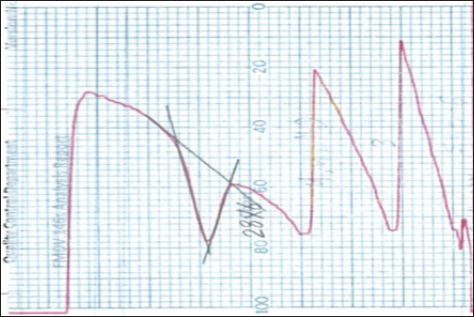

Fig. 6. Temporal dynamics of FMDV production and cell viability across passages. The upper panel (a) shows virus titers (blue line, left y-axis) and cell viability (red line, right y-axis). The lower panel (b) displays VCD distribution across FMDV passages. 146s Quantification of virus harvesting from BHK-S and adherent cellsQuantification of viral yield revealed that BHK-S cells produced significantly higher concentrations of FMDV particles compared with conventional adherent cultures. Analysis of 146S particles by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation (Fig. 10) demonstrated that virus harvested from suspension-adapted BHK-S cells yielded 4.42 μg/ml of intact viral particles, which was approximately three-fold higher than the yield obtained from traditional BHK adherent cells (1.5 μg/ml) under identical infection conditions (MOI=0.001). This substantial increase in viral yield suggests that the adaptation of BHK cells to suspension culture not only maintained their susceptibility to FMDV infection but also enhanced their capacity for virus production, making the suspension culture system a more efficient platform for FMDV antigen production.

Fig. 7. Comparisons between the infectivity titer of FMDV in both adherent and suspension BHK cells at the same MOI and under the same conditions.

Fig. 8. Gel electrophoresis of the PCR product of FMDV harvested from BHK-S. DiscussionThe development of efficient production systems for FMDV vaccines remains a critical challenge in veterinary medicine and biotechnology, particularly in resource-limited settings. Our study provides comprehensive evidence that suspension-adapted BHK cells (BHK-S) offer significant advantages for FMDV production, with implications for industrial-scale vaccine manufacturing. A key contribution of this work is the successful implementation of a cost-effective suspension adaptation strategy using a rolling system with gradual speed increment (20–60 rpm over 10 passages). This methodological innovation addresses a critical need in developing countries, where access to sophisticated bioreactor systems may be limited or cost-prohibitive. Being able to adapt adherent cells to grow in suspension is a major step forward for vaccine production. When companies can develop their own suspension cell lines in-house, they become less reliant on buying pre-adapted cells from outside suppliers—which are often expensive and can come with risks such as contamination, cell death, or unexpected shortages. These issues can slow production and increase costs. However, by successfully transitioning adherent cells into stable suspension cultures, manufacturers can scale up the process more easily and consistently, making vaccine development and production more efficient and sustainable. The rolling adaptation method achieved performance metrics comparable to those of conventional techniques, with cells maintaining viability above 85% and achieving viral titers of 109.5 TCID50/ml. This approach allows the growth adaptation of each cell line from the adherent state to the growth state to be applied and used at a manufacturing scale. Thus, it is particularly valuable for vaccine manufacturing facilities in resource-constrained settings. Furthermore, systematic analysis of this production platform revealed several key advances, including enhanced viral yield, genetic stability, and scalability. The success of this method demonstrates that effective suspension adaptation can be achieved without sophisticated equipment, potentially democratizing access to efficient FMDV vaccine production technology. These findings align with recent studies emphasizing the importance of developing cost-effective production strategies for emerging economies and underscoring the broader relevance and impact of this work in addressing global vaccine production challenges.

Fig. 9. Shows the differences in cell growth over 48 hour in the bioreactor and 146s between BHK-adherent and BHK-S.

Fig. 10. Sucrose density gradient analysis of FMD virus harvested from suspension-adapted BHK-21 cells (BHK-S). The presence of the 146S peak confirms the successful concentration of intact viral particles. The adaptation of BHK cells to suspension culture resulted in remarkably enhanced FMDV production capacity. Suspension-adapted cells consistently achieved viral titers 2–3 logs higher than conventional adherent cultures, with peak titers reaching 109.5 TCID50/ml compared to 106.8 TCID50/ml in adherent systems. This substantial improvement aligns with recent findings by Ghafoor et al. (2025), who successfully established an optimized protocol for adapting and cultivating BHK-21 cells in suspension within a bioreactor, achieving high cell densities essential for efficient vaccine manufacturing (Ghafoor et al., 2025). These findings lay the foundation for industrial-scale FMD vaccine production in Pakistan and other similar settings (Razak et al., 2023). Notably, our system maintained elevated titers (107–08.75 TCID50/ml) across multiple passages, demonstrating robust and consistent production capacity. The strong correlation between virus titer and cell viability (r=0.967, p < 0.001) provides valuable insights into the relationship between cellular health and viral productivity, supporting observations by Thompson et al. (2023) regarding metabolic optimization in suspension cultures. The molecular characterization of viral propagation through PCR analysis targeting the 1D/2B region yielded consistent 402-bp products across passages (P1, P3, P5, P7, and P9), confirming the maintenance of viral genetic integrity throughout the adaptation process. This finding is critical for ensuring the antigenic fidelity of FMDV vaccines because genetic drift during cell culture adaptation can compromise vaccine efficacy (Rodriguez-Limas et al., 2023). The uniform band intensity observed in gel electrophoresis, coupled with the absence of nonspecific amplification products, highlights the reliability of the suspension culture system for consistent antigen production. Quantitative analysis of viral yield revealed that BHK-S cells produced 4.42 μg/ml of 146S particles, a three-fold increase compared with adherent cultures (1.5 μg/ml). This improvement in antigen yield is particularly significant for industrial-scale vaccine production, where maximizing antigen output is critical for cost-effectiveness. The successful scale-up of the suspension culture system to a 10-l bioreactor further underscores its potential for large-scale manufacturing. Under controlled conditions, the system demonstrated stable cell growth, high viability, and consistent viral yields, providing a robust platform for the production of FMDV vaccines. Despite these advancements, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study did not investigate the long-term stability of suspension-adapted BHK-S cells beyond nine passages. Future studies should assess the genetic and phenotypic stability of these cells over extended passages to ensure their reliability for continuous production. Second, although enhanced viral yield and antigen production were observed, the underlying molecular mechanisms driving these improvements remain unclear. Investigating the metabolic and transcriptional changes in BHK-S cells during adaptation could provide valuable insights into the factors contributing to their enhanced productivity. The economic and industrial implications of this study are significant. The three-fold increase in antigen yield achieved in suspension culture can potentially reduce production costs and increase the availability of FMD vaccines, particularly in resource-limited settings. The scalability and reproducibility of the BHK-S system make it an attractive platform for commercial vaccine manufacturing, addressing critical challenges in meeting the global demand for FMD vaccines. Furthermore, the adaptability of this platform to the emerging FMDV strains underscores its potential to address the evolving nature of the disease and maintain the efficacy of vaccination programs. In conclusion, this research provides valuable insights into the scalable production of FMDV, with clear evidence supporting the superiority of suspension culture systems for large-scale manufacturing. These findings contribute significantly to the field of veterinary vaccine production and offer a foundation for future process optimization and scale-up strategies. The successful demonstration of enhanced 146S particle production in suspension culture, coupled with improved cell viability and growth characteristics, presents a promising platform for industrial-scale FMDV vaccine manufacturing. These results provide a robust framework for the future development and optimization of large-scale production processes with the potential to enhance the availability and affordability of FMD vaccines in endemic regions. ConclusionThis research provides valuable insights into the scalable production of FMDV, with clear evidence supporting the superiority of suspension culture systems for large-scale manufacturing. These findings contribute significantly to the field of veterinary vaccine production and offer a foundation for future process optimization and scale-up strategies. The suspension culture method not only demonstrated superior 146S antigen production but also proved to be a scalable and efficient platform for FMDV vaccine manufacturing. These findings provide a strong foundation for further optimization and industrial implementation of suspension-adapted BHK-21 cells for vaccine production. The successful demonstration of enhanced 146S particle production in suspension culture, coupled with improved cell viability and growth characteristics, presents a promising platform for industrial-scale FMDV vaccine manufacturing. These results provide a robust framework for the future development and optimization of large-scale production processes. AcknowledgmentsNone. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests. FundingAdaptation to the suspension stage of BHK-21 cells was funded by the Egyptian Company for Biological & Pharmaceutical Industries (Vaccine Valley), Egypt. The scaling-up stage was funded by the Veterinary Serum and Vaccine Research Institute. Authors’ contributionsSoad Eid, A. A. Yousif, and M. A. Shalaby conceptualized the study and designed the experiments. Dalia Ayman, Mahmoud Ali, and Soad Eid performed adaptation of BHK adherent cells to grow in suspension, infectivity titration, and PCR. Soad Eid prepared the figures and the table. Soad Eid and Sonia Rizk wrote the main manuscript text. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the Analysis of Data and Writing manuscript. Data availabilityThe datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All materials used in this study are also available upon request, subject to institutional and ethical guidelines. ReferencesAbercrombie M. 1978. Fibroblasts. J. Clin. Patho.l Suppl. 12, 1–6. Alexandersen, S., Zhang, Z., Donaldson, A.I. and Garland, A.J.M. 2003. The pathogenesis and diagnosis of foot-and-mouth disease. J. Comp. Pathol. 129, 1–36; doi:10.1016/S0021-9975(03)00041-0. Aunins, J.G. 2020. Viral vaccine production in cell culture. In Encyclopedia of industrial biotechnology, bioprocess, bio separation, and cell technology; Vol. 1. Ed. Flickinger, M.C. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; pp: 1–27. Butler, M., Molitoris, E. and Reichl, U. 2020. Bioprocess applications of suspension cell cultures. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 65, 254–261; doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2020.03.003. Byomi, A., Zidan, S., Sakr, E., Eissa, N., and Elsobky, Y. 2023. Epidemiological patterns of foot and mouth disease in Egypt and other African countries. J. Curr. Vet. Res. 5(1), 250–282. Capstick, P.B., Telling, R.C., Chapman, W.G. and Stewart, D.L. 1962. Growth of a cloned strain of hamster kidney cells in suspended cultures and their susceptibility to the virus of foot-and-mouth disease. Nature 195, 1163–1164; doi:10.1038/1951163a0. DeliveReD, G. 2012. Animal cell culture guide. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Doel, T.R. 2003. FMD vaccines. Virus Res. 91, 8199; doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00261-7. Domingo, E., Sheldon, J. and Perales, C. 2012. Viral quasispecies evolution. Microbial. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 159–216; doi:10.1128/MMBR.05023-11. EL-Kholy, A.A., Soliman, H.M.T. and Abdel Rahman, A.O. 2007. Molecular typing of a new foot-and-mouth disease virus in Egypt. Vet. Rec. 160, 695–697; doi:10.1136/vr.160.20.695. EL-Shehawy, L., Abu-Elnaga, H., Abdel Atty, M., Fawzy, H., Al-Watany, H. and Azab, A. 2011. Laboratory diagnosis of FMD using real-time RT-PCR in Egypt. Life Sci. J. 8, 384–387. El-Shehawy, L., Abu-Elnaga, H., Rizk, S., Abd El-Kreem, A., Elbeltagy, A. and Azab. W. 2022. Molecular characterization of foot-and-mouth disease viruses in Egypt (2016-2021): Vet. World 15, 1008–1019; doi:10.14202/vetworld.2022.1008-1019. El-Tholoth, M. and El-Kenawy, A.A. 2022. Production and quality control of foot-and-mouth disease vaccines in Egypt: current challenges and future perspectives. Vaccine 40, 2876–2883; doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.002. Grubman, M.J. and Baxt, B. 2004. Foot-and-mouth disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17(2), 465–493. Genzel, Y. and Reichl, U. 2021. Continuous cell lines as a production system for influenza vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 20, 597–612; doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1915727. Genzel, Y. 2015. Designing cell lines for viral vaccine production: where do we stand? Biotechnol. J. 10, 728–740; doi:10.1002/biot.201400388. Ghafoor, A., Altaf, I., Anjum, A. A. and Awan, A. R. 2025. Optimization of suspension culture of adapted baby hamster kidney cells in a bioreactor for maximum cell density. Sci. Asia 51, 18; doi:10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2025.013. Hegazy, Y.M., Molina-Flores, B., Shafik, H., Ridler, A.L. and Guitian, F.J. 2021. Foot-and-mouth disease in Egypt: effectiveness of control program and vaccine quality assessment. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 68, 531–541; doi:10.1111/tbed.13726. Hema, M., Nagendrakumar, S.B., Yamini, R., Chandran, D. and Kumar, S. 2021. Advances in cell culture technology for foot-and-mouth disease virus vaccine production. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 657094; doi:10.3389/fvets.2021.657094. Kallel, H., Rourou, S., Majoul, S. and Loukil, H. 2019. A novel process for the production of a veterinary rabies vaccine in BHK-21 cells grown on microcarriers in a 20-L bioreactor. Appl. Microbial. Biotechnol., 103, 1131–1141; doi:10.1007/s00253-018-9532-6. Kandeil, A., El-Shesheny, R., Kayali, G., Moatasim, Y., Bagato, O., Darwish, M., Gaffar, A., Kutkat, M.A., Ahmed, M.A. and Ali, M.A. 2023. Characterization of recent foot-and-mouth disease virus isolates from Egypt, 2016-2022. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 70,197–208; doi:10.1111/tbed.14532. Kappes, A., Tozooneyi, T., Shakil, G., Railey, A.F., McIntyre, K.M., Mayberry, D.E., Rushton, J., Pendell, D.L. and Marsh, T.L. 2023. Livestock health and disease economics. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 10546065. Knight-Jones, T.J.D. and Rushton, J. 2013. The economic impacts of foot and mouth disease - What are they, how big are they and where do they occur? Prev. Vet. Med. 112,161–173; doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.07.013. Kotecha, A., Seago, J., Scott, K., Burman, A., Loureiro, S., Ren, J., Porta, C., Ginn, H.M., Jackson, T., Perez-Martin, E., Siebert, C.A., Paul, G., Huiskonen, J.T., Jones, I.M., Esnouf, R.M., Fry, E.E., Maree, F.F., Charleston, B. and Stuart, D.I. 2015. Structure-based energetics of protein interfaces guides foot-and-mouth disease virus vaccine design. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 788–794; doi:10.1038/nsmb.3096. Krause, P.R., Fleming, T.R., Peto, R., Longini, I.M., Figueroa, J.P., Sterne, J.A., Cravioto, A., Rees, H., Higgins, J.P., Boutron, I. and Pan, H. 2021. Considerations in boosting COVID-19 vaccine immune responses. Lancet 398(10308), 1377–1380. Kumar, S.R., Markosyan, N. and Sharma, P. 2020. Comparison of upstream process strategies for FMDV vaccine manufacturing: suspension versus adherent cell culture. Vaccine 38, 7148–7158; doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.027. Lei, C., Yang, J., Hu, J. and Sun, X. 2021. On the calculation of TCID50 for quantitation of virus infectivity. Virol. Sin. 36(1), 141–144. Mahapatra, M. and Parida S. 2018. Foot and mouth disease vaccine strain selection: current approaches and future perspectives. Expert Rev. Vacc. 17, 577–591; doi:10.1080/14760584.2018.1492378. Mason, P.W., Grubman, M.J. and Baxt, B. 2003. Molecular basis of pathogenesis of FMDV. Virus Res. 91, 9–32; doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00257-5. Mowat, G.N. and Chapman W.G. 1962. Growth of foot-and-mouth disease virus in a fibroblastic cell line derived from hamster kidneys. Nature 194, 253–255; doi:10.1038/194253a0. Nema, R. and Khare, S. 2012. An animal cell culture: advance technology for modern research. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 3, 219–226. Paton, D.J., Sumption, K.J. and Charleston, B. 2009. Options for control of foot-and-mouth disease: knowledge, capability and policy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B, Biol. Sci. 364(1530), 2657–2667. Pay, T.W.F. and Hingley, P.J. 1987. Correlation of 140S antigen dose with the serum neutralizing antibody response and the level of protection induced in cattle by foot-and-mouth disease vaccines. Vaccine 5, 60–64; doi:10.1016/0264-410X(87)90061-4. Park, S., Kim, J. Y., Ryu, K.-H., Kim, A.-Y., Kim, J., Ko, Y.-J. and Lee, E. G. 2021. Production of a foot-and-mouth disease vaccine antigen using suspension-adapted BHK-21 cells in a bioreactor. Vaccines 9(5), 505; doi:10.3390/vaccines9050505 Razak, A., Altaf, I., Anjum, A.A. and Awan, A.R. 2023. Preparation of purified vaccine from local isolate of foot and mouth disease virus and its immune response in bovine calves. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 30(7), 103709. Rodriguez-Limas, W.A., Sekar, K. and Tyo, K.E. 2023. Quality parameters in viral vaccine manufacturing. Vaccine 41, 245–257; doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.057. Shahen, N.M., Aboezz, Z.R.A., Elhabba, A.S., Hagaa, N. and Sharawi, S.S.A. 2020. Molecular matching of circulating foot and mouth disease viruses and vaccinal strains in Egypt, 2016–2019. Benha Vet. Med. J. 39(1), 132–137. Strober, W. 2001. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Appendix 3: Appendix 3B; doi:10.1002/0471142735.im0303bs20. Strober, W. 2015. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Appendix 3: Appendix 3B. Telling, R.C. and Elsworth, R. 1965. Submerged culture of hamster kidney cells in a stainless-steel vessel. Biotechnol. Bioeng, 7, 417–434; doi:10.1002/bit.260070312/ Thompson, B., Anderson, D., Chen, X. and Liu, Y. 2023. Cellular adaptations enhancing viral production in suspension cultures. Trends Biotechnol. 41, 178–190; doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.09.003. Yousef, S.G., Damaty, H.M.E., Elsheikh, H.A., El-Shazly, Y.A., Metwally, E. and Atwa, S. 2025. Genetic characterization of foot-and-mouth disease virus in cattle in Northern Egypt. Vet. World 18(1), 238–248. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Eid S, Rizk SA, Ayman D, Ali M, Saad M, El-sanousi AA, Yousif AA, Shalaby MA. Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 Web Style Eid S, Rizk SA, Ayman D, Ali M, Saad M, El-sanousi AA, Yousif AA, Shalaby MA. Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=263811 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Eid S, Rizk SA, Ayman D, Ali M, Saad M, El-sanousi AA, Yousif AA, Shalaby MA. Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Eid S, Rizk SA, Ayman D, Ali M, Saad M, El-sanousi AA, Yousif AA, Shalaby MA. Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(7): 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 Harvard Style Eid, S., Rizk, . S. A., Ayman, . D., Ali, . M., Saad, . M., El-sanousi, . A. A., Yousif, . A. A. & Shalaby, . M. A. (2025) Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. Open Vet. J., 15 (7), 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 Turabian Style Eid, Soad, Sonia A. Rizk, Dalia Ayman, Mahmoud Ali, Mohamed Saad, Ahmed A. El-sanousi, Ausama A. Yousif, and Mohamed A. Shalaby. 2025. Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 Chicago Style Eid, Soad, Sonia A. Rizk, Dalia Ayman, Mahmoud Ali, Mohamed Saad, Ahmed A. El-sanousi, Ausama A. Yousif, and Mohamed A. Shalaby. "Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Eid, Soad, Sonia A. Rizk, Dalia Ayman, Mahmoud Ali, Mohamed Saad, Ahmed A. El-sanousi, Ausama A. Yousif, and Mohamed A. Shalaby. "Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings." Open Veterinary Journal 15.7 (2025), 3193-3205. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Eid, S., Rizk, . S. A., Ayman, . D., Ali, . M., Saad, . M., El-sanousi, . A. A., Yousif, . A. A. & Shalaby, . M. A. (2025) Cost-effective suspension adaptation of BHK-21 cells for scalable FMD vaccine production in resource-limited settings. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3193-3205. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.30 |