| Original Article | ||

Open Vet J. 2022; 12(2): 156-164 Open Veterinary Journal, (2022), Vol. 12(2): 156–164 Original Research Case study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint: A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary cliniciansMichela Pugliese1*, Rocky La Maestra1, Annalisa Previti2, Annastella Falcone1, and Annamaria Passantino11Department of Veterinary Sciences, University of Messina – Via Umberto Palatucci, 98168 Messina, Italy 2Clinica Veterinaria ‘Zampiland’ – Via Calamaro 23, 98040 Villafranca Tirrena, Messina, Italy *Corresponding Author: Michela Pugliese. Department of Veterinary Sciences, University of Messina Via Umberto Palatucci, Messina, Italy. Email: mpugliese [at] unime.it Submitted: 07/09/2021 Accepted: 27/01/2022 Published: 01/03/2022 © 2022 Open Veterinary Journal

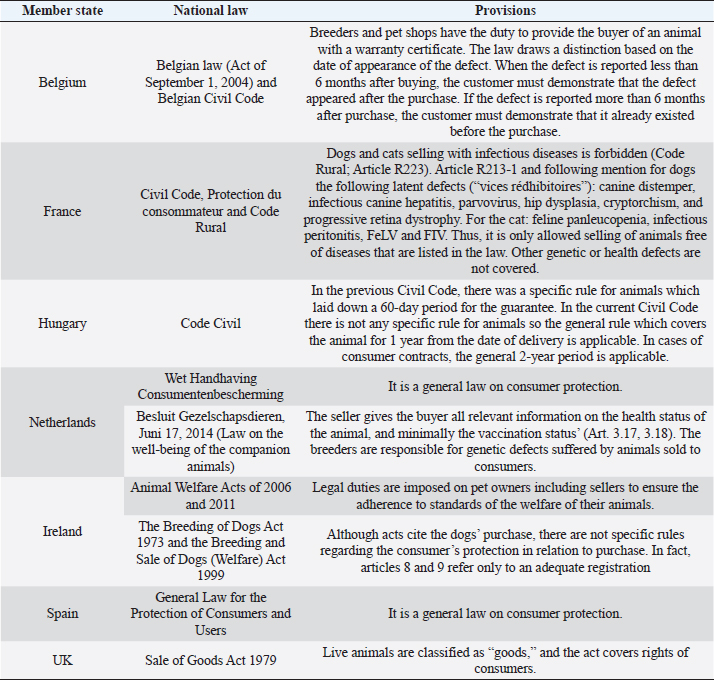

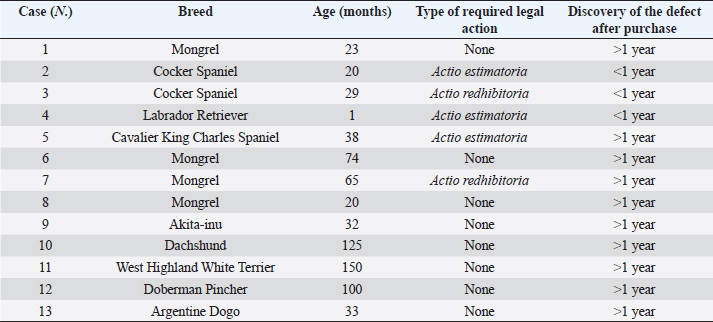

AbstractBackground: Despite pets are sentient beings, they are legally considered and regulated as objects in sales contracts. Therefore, the buyer is protected by law if the purchased animal should be affected by defects such as an illness or a congenital / hereditary condition that depreciates its value. In the sale of animals, a disease is legally considered a defect if it is hidden, severe, and pre-existing at the time of purchase. Canine Atopic Dermatitis (CAD) having these three requirements can, therefore, legally be considered a defect. To acquire his legal rights, the buyer must obtain a certification from the veterinarian reporting that the animal was unfit for buying within a certain time frame. Aim: This paper analyzes the legal choices that owners of dogs affected with CAD can make to help practicing veterinary clinicians comprehend and recognize this disease and because it may be considered a defect. Methods: Thirteen cases of CAD are reported and analyzed from a medico-legal point of view. Results: In cases n. 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 owners of dogs affected with CAD partial or full reimbursement from the seller obtained. In cases n. 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13, dog owners could not take any legal action because the diagnosis of CAD was made beyond the time limits required by law. In cases n. 1, 6, and 8, the owners decided not to take any legal action. Conclusion: The veterinarian practitioner is a key professional figure not only for diagnosing the disease within the legal time limits, but also for support the owner in medico-legal disputes. A basic medico-legal background for all veterinarians and greater involvement of them in the sale of animals as a guarantee for the buyer is recommended. Keywords: CAD, Canine atopic dermatitis, Skin disease, Clinical signs, Purchase defect. IntroductionCanine Atopic Dermatitis (CAD) is defined as “a genetically predisposed, inflammatory and pruritic allergic skin disease, which is most commonly associated with the presence of IgE antibodies directed against environmental or food allergens or both” (Olivry, et al., 2001; Halliwell, 2006). Genetic factors are considered as very important in dogs and humans (Sousa and Marcella, 2001; Morar et al., 2006). Studies suggest that CAD involves numerous genes interacting with environmental elements (Sousa and Marcella, 2001; Morar et al., 2006; Wilhem et al., 2011; Nuttal et al., 2013). CAD is common in dogs, affecting between 3% and 15% of the canine population or up to 58% of dogs affected by skin diseases (Hillier and Griffin, 2001; Nødtvedt et al., 2006). The most involved canine breeds are French bulldog, Scottish terrier, Fox Terrier, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Boxer, Labrador Retriever, German shepherd, Dalmatian, Shar Pei, West Highland white terrier, and Jack Russell (Nødtvedt et al., 2006; Wilhem et al., 2011). It is also possible that each dog breed shows a different CAD clinical presentation based on its genetics pool (Wilhem et al., 2011). Therefore, the lesions can vary in location, severity, and age of onset (Griffin and DeBoer, 2001; Favrot et al., 2010; Eisenschenk, 2020). Clinical signs onsets usually between 6 months and 3 years. The first symptom is generally persistent itching, followed by erythema, papules, and pustules, defined as “primary skin lesions” (Griffin and DeBoer, 2001; Favrot et al., 2010; Eisenschenk, 2020). There are “secondary skin lesions” in chronic CAD, such as alopecia, cutaneous lichenification, and often bacterial infections (DeBoer and Griffin, 2001; Griffin and DeBoer, 2001; Favrot et al., 2010; Eisenschenk, 2020). Dogs with CAD present alterations in epidermal integrity combined with cutaneous hyperactivity due to reduced production of filaggrin and ceramides, which causes water loss and increased entry of allergens (Drislane and Irvine, 2019; Combarros et al., 2020). The latter provokes a continuous and persistent immune response mediated by mast cells, IgE, and Th2 response (Marsella et al., 2012). CAD is also a diagnostic challenge. Pathognomonic signs or specific biomarkers have not been identified. The diagnosis is generally made to exclude other diseases with similar symptoms, such as ectoparasitic infestations and the application of “Fravrot criteria” (Hill et al., 2006; Hensel et al., 2015). Allergy tests used are the evaluation of skin reactivity by Intra Dermal Testing or the detection of IgE by Allergen-Specific IgE Serology (ASIS) test (Hill et al., 2006; Hensel et al., 2015). Allergy tests aim to detect allergens to be avoided or contained in allergen-specific immunological therapy, which improves clinical signs of CAD patients by administering an increasing number of allergens (Hill et al., 2006; Hensel et al., 2015). The symptomatic treatment of CAD instead, consists of the administration of topical or systemic glucocorticoid, oclacitinib, implementation of a flea control regime, dietary supplementation with essential fatty acids, antibiotic treatment, frequent shampoos, avoidance of allergens (Olivry and Saridomichelakis, 2013; Olivry et al., 2015; Santoro, 2019). The veterinarian should be able to recognize CAD because it may be considered a defect in animal buying and selling and consequently be the object of civil lawsuits. In this article no. 13, case study on CAD were evaluated from a medico-legal viewpoint. The aim was to provide veterinary clinical practitioners with the knowledge and skills necessary to recognize this disease as a redhibitory defect competently. Each case required problem-solving skills and communication with the owner. Legal backgroundAlthough the pets occupy the status of a beloved family member, they are legally considered property (Passantino and Vico, 2006). During the sales process, the animals are categorized as mere goods, where the term “goods” is meant to afford purchasers and vendors certain rights and responsibilities in the contract (Eur-Lex.eu, 2005; Masucci and Passantino 2006; Eur-Lex.eu, 2011; Europa.eu, 2019). According to the law, i.e., in Italy, the animals are res (article 812 of the Civil Code). Their sale is therefore regulated by article 1470. Following the Civil Code (c.c.), which deals with the sale of goods in general, and by article 1496 c.c., specifically regulates the animals’ sale (Di Majo, 2017). The Italian Civil Code states that the seller is obliged to guarantee that the thing sold is free from defects that make it unsuitable for the use to which it is destined or that appreciably impairs its value (Di Majo, 2017). The same provisions are established by the Consumer Sales and Guarantees Directive that ensures consumers a legal guarantee for material goods, including cats and dogs (Eur-Lex.eu, 1999). Although the European directive does not explicitly address pet animals, the rules laid down in the Directive could very well be applied to contracts relating to the animal purchase. In fact, at the European level, consumer protection concerning animal purchase is founded on the general consumer protection laws. In some countries, national governments have adopted rules concerning animal welfare rather than consumers’ protection during the purchase of an animal in lousy health status with potential defects, problems, and, hereditably diseases. Table 1 reports the national law in some Member States. In the US, several states have pet purchase protection laws providing legal recourse to pet owners who purchase animals from dealers/breeders when those pets are later found to have a defect (AVMA, 2021). The time frame to exercise buyer remedies varies from 7 to 25 days for illness and diseases and, 10 days to 2 years for congenital or hereditary defects. Generally, all the states prescribe the same remedies, allowing buyers to either return the pet for reimbursement of purchase price or replace the pet for another comparable value chosen by himself/themselves. In this last case, the replacement can be associated with reimbursement for veterinary expenses (i.e., related to certification that animal is unfit for purchase or the diagnosis and the treatment) in an amount of not more than the original purchase price of the animal. Some states also allow buyers to retain the pet and receive the reimbursement of veterinary expenses, reflecting the strong bond established with the unfit animal for sale. In states without a specific law, consumers result in relief under the Uniform Commercial Code, which regulates the sale of goods. In Australia, a pet purchase is just like any other purchase made by a consumer; it is covered by the Australian Consumer Law. Also, in Canada, the Consumer Protection Act treats pets as consumer goods, and consequently, the same regulations are applied. Therefore, in the eyes of the law buying a pet is the same as buying any other product. Thus the animal automatically should become with the following consumer guarantees, to make sure she/he gets what she/he paid for:

It is important to understand the meaning of defect. In veterinary legal medicine, a defect or disease can be considered a vice only if it has these requirements (Passantino, 2006; Quartarone et al., 2012):

Suppose the animal sold does not meet the above-said requirements or is suffering from a serious or chronic vice that is pre-existing and not easily recognizable. In that case, the buyer may elect one of the following options once a veterinarian certifies that the purchased animal is unfit:

In death cases of the animal from causes not caused by an accident, the buyer may be entitled to a full reimbursement of the animal’s purchase price or have another animal of his/her choice of correspondent value, plus reimbursement of veterinary fees. Table 1. Pet purchase protection law in some Member States.

For example, Italian law allows the buyer to proceed with one of the two types of legal actions, namely the actio redhibitoria, in which the buyer returns the animal and is refunded, or the actio estimatoria (quanti minoris), in which the buyer keep the animal and obtains restitution of a part of the price that is a compensation proportionate for the loss of value (article 1942 c.c.). They are also entitled to refund the expenses caused by the sale and any heads of damages suffered. There exists a finite time frame under which a buyer may recess the contract of sale and return an animal or receive other compensation. This time frame changes from state to state. Under EU legislation, 27 consumers are granted 6 months during which complaints of defect can be raised; this period is inappropriate, in our opinion, since hereditary diseases would not necessarily become apparent within such a time frame. In Italy, any legal action must be taken within 8 days of the discovery of the vice and, in any case no later than 1 year following the purchase of the animal (period of prescription extinction) (article 1945 c.c.). Materials and MethodsAnimalsDigital medical records from April 2015 to August 2019 from a veterinary clinic with expertise regarding animal law (Messina, Southern Italy) were searched for the following terms: itching, alopecia ear infection, lichenification, crusting, erythema, hyperpigmentation, furfuraceous dermatitis, epidermal collarettes, conjunctivitis, bad smell, and in some cases, papules, pustules, excoriations, and pyoderma. Dogs with a complete medical record, compatible clinical signs, and a diagnosis of CAD confirmed by ASIS were included in this study. CAD was revealed in 13 dogs (5 females and 8 males) of a different breed—mongrel dogs (4/13: 30.7%), Cocker Spaniel (2/13: 15.3%), Labrador Retriever (1/13: 7.6%), Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (1/13: 7.6%), Akita-Inu (1/13: 7.6%), Dachshund (1/13: 7.6%), West Highland White Terrier (1/13: 7.6%), Doberman Pincher (1/13: 7.6%), Argentine Dogo (1/13: 7.6%). Real cases studyDogs affected by CAD showed itching (13/13: 100%), alopecia (9/13: 69.2%), ear infection (6/13: 46.1%), lichenification (5/13: 38.4%), crusting (4/13: 30.7%), erythema (4/13: 30.7%), hyperpigmentation (4/13: 30.7%), furfuraceous dermatitis (4/13: 30.7%), epidermal collarettes (2/13: 15.3%), conjunctivitis (2/13: 15.3%), bad smell (2/13: 15.3%), papules (1/13: 7.6%), pustules (1/13: 7.6%), excoriations (1/13: 7.6%), pyoderma (1/13: 7.6%), weight decrease (1/13: 7.6%). After the diagnosis of CAD, the veterinarian informed the owner about the possibility of taking legal action against the seller within 8 days from the discovery of the disease, and in any case, within 1 year of dog purchase (in accordance with article 1490 of Italian Civil Code). Undertaken legal actions are summarized in Table 2. Ethical approvalThis study was conducted following the ethical principles of the Code of Ethics of Veterinarians and with Italian and European regulations on animal welfare. All information was collected according to the principles of correctness, lawfulness, transparency, protection of privacy, rights of the person concerned, Article 13 of Italian Legislative Decree no. 196/2003, and the European General Data Protection Regulation 679/2016 (GDPR) (Passantino, et al., 2012). Table 2. Type of undertaken litigation cases.

Fig. 1. Dog affected by CAD, showing intense itching, and also lichenification, alopecia and hyperpigmentation.

Fig. 2. Detail of skin thickening around the eyes. ResultsIn cases n. 2, 4, and 5, the owners required an estimatory action and retained the animal. All obtained a partial reimbursement of the purchase price, commensurate with the loss of value that is a consequence of the defect. However, in case n. 5, the diagnosis of CAD came after the year of the normal warranty. However, in this latter case, the parties (seller and buyer) had a private contract to extend the warranty period beyond the year. For this reason, it was possible to obtain a partial refund. In case 3, the owner requested a redhibitory action. The seller agreed to pay the full refund relating to the dog’s purchase price and reimbursement for reasonable veterinary fees for the diagnosis of the disease. Concerning case n. 7, a redhibitory action was requested, but the sterilization after the purchase was interpreted as property action on the animal. The owner is legally obliged to return the animal in the same condition it was sold to request a refund. The dog remained with the buyer, and only an estimatory action was permitted, leading to partial compensation of the purchase price. The move was aimed at “proportionally maintaining unchanged the initial equivalence ratio between the contract price and goods”. In the opinion of Rubino (1972), it is not a form of partial cessation of the contract but a partial and exceptional form of compensations. The justification behind this is the difference between the corresponded price and the lower price than the buyer would have had to pay if he/she had recognized the vices from the outset. In cases n. 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13, dog owners have discovered the disease beyond the 1-year warranty period and therefore could not proceed with any legal action. In cases n. 1, 6, and 8, the owners have decided not to take any legal action. DiscussionAlthough the medico-legal approach to diseases characterized by a multifactorial etiopathogenesis and variability of symptoms, like CAD, is more difficult than in conditions for which a recognized causal factor can be identified, CAD falls within the category of “vices,” since it satisfies the requirements of pre-existence, hiding, and chronicity/severity. It is a disease: Pre-existing: The genetic predisposition is considered a key factor for the onset of the disease; Hidden: It can be asymptomatic for long periods; Chronic or severe: CAD persists throughout the dog’s life, requiring continuous treatments; it can also seriously impact animal welfare and its value. The diagnosis is often long and difficult. Moreover, this defect may take months or years to manifest itself (Wilhem et al., 2011). The warranty period is therefore often insufficient to reach the diagnosis of CAD. It should be considered how long it may take for clinical signs of this disease to become evident. This means that deciding when a legal claim can be conceded and/or what can be reimbursed is often a delicate task. To appropriately address congenital/inheritable disorders, an option that might be pondered is to produce a range of warranties based on the nature of the pathologic condition. In described scenarios, the veterinarian could suggest signing a written agreement and extending the warranty period concerning hereditary defects. This agreement should contain the following information regarding the pet: species, breed, date of birth, gender, color, and individual identifying microchip number. Also, it should include a statement that a veterinarian examined the pet, and during the examination, it showed no apparent or clinical symptoms of a severe health problem that would adversely affect its health at the time of sale. An example of a written agreement is shown in Appendix 1. ConclusionSince it appears likely that relatively few practicing clinicians can be expected to be familiar with the legal issues involving the animals, legal education in the veterinary curriculum is very important (Babcock and Hambrick, 2006). Indeed, the changing status of animals in the legal system is gradually contributing to the need to include training about legal disputes in veterinary practice into the traditional veterinary curriculum. With this in mind, the veterinarian must be familiar with the issues arising in the courts regarding the animal purchase, so that they can be a decision-maker in the changing trends in veterinary law and medicine. In conclusion, knowledge of these cases study is expected to guide the future practitioner through the specificity of the situations they will eventually confront. Conflict of interestWe confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication. Consent to participateWritten informed consent has been obtained from each pet owners for publish this paper. Author contributionsConceptualization, A.P; methodology, A.P.; validation, A.P., M.P; formal analysis, R.L.M..; investigation, A. Pr.; resources, A. Pr.; data curation, R.L.M.; writing-original draft preparation, A.P, R.L.M.; writing-review and editing, A.P., M.P., A.F.; visualization, M.P..; supervision, A.P., M.P.; project administration, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Animal welfare statementThe authors confirm that the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal’s author guidelines page, have been adhered to and the appropriate ethical review committee approval has been received. The authors confirm that they have followed EU standards for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Institutional Review Board statementThe study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Code of Ethics of Veterinarians and with Italian and European regulations on animal welfare. All information was collected according to the principles of correctness, lawfulness, transparency, protection of privacy, rights of the person concerned, article 13 of Italian Legislative Decree no. 196/2003, and the European General Data Protection Regulation 679/2016 (GDPR). Ethical review and approval were not required for this study, due for non-interventional studies ethical approval is not necessary (national laws). ReferencesAVMA. 2021. American Veterinary Medical Association. In Pet purchase protection laws. Available via https://www.avma.org/advocacy/state-local-issues/pet-purchase-protection-laws Babcock, S.L. and Hambrick, D.Z. 2006. Toward a practice-based approach to legal education in the Veterinary Medical Curriculum. J.V.M.E. 33(1), 125–31. Combarros, D., Cadiergues, M.C. and Simon, M. 2020. Update on canine filaggrin: a review. Vet. Q. 40(1), 162–8. DeBoer, D.J. and Hillier, A. 2001. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XV): fundamental concepts in clinical diagnosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 81(3-4), 271–6. Di Majo, A. 2017. Codice civile. Milano, Italy: Giuffrè editore. Drislane, C. and Irvine, A.L. 2019. The role of filaggrin in atopic dermatitis and allergic disease. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 124(1), 36–43. Eisenschenk, M. 2020. Phenotypes of canine atopic dermatitis. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 9, 175–80. Eur-Lex.eu. 2005. Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices. Off. J. Eur. Uni. 22. Available via https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:149:0022:0039:EN:PDF Eur-Lex.eu. 2011. Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on Consumer Rights. Off. J. Eur. Uni. 64. Available via https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32011L0083 Eur-Lex.eu. 1999. European Parliament Directive 1999/44/EC on certain aspects of the sale of consumer goods and associated guarantees. Off. J. Eur. Uni. 12–6. Available via https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A31999L0044. Europa.eu. 2019. Directive 2019/2161/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules. 7–28. Available via https://op.europa.eu/it/publication-detail/-/publication/eefb17ee-2173-11ea-95ab-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-HTML Favrot, C., Steffan, J., Seewald, W. and Picco, P. 2010. A prospective study on the clinical features of chronic canine atopic dermatitis and its diagnosis. Vet. Dermatol. 21(1), 23–31. Griffin, C.E. and DeBoer, D.J. 2001. The ACVD task force of canine atopic dermatitis (XIV): clinical manifestation of canine atopic dermatitis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 81(3-4), 255–69. Halliwell, R. 2006. Revised nomenclature for veterinary allergy. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 114(3-4), 207–8. Hensel, P., Santoro, P., Favrot, C., Hill, P. and Griffin, C. 2015. Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. B.M.C. Vet. Res. 11, 196. Hill, P.B., Lo, A., Eden, C.A.N., Huntley, S., Morey, V. and Ramsey, S., 2006. Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice. Vet. Rec. 158(16), 533–9. Hillier, A. and Griffin, C.E. 2001. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (I): incidence and prevalence. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 81(3-4), 147–51. Marsella, R., Sousa, C.A., Gonzales, A.J. and Fadok, V.A. 2012. Current understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms of canine atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 241(2), 194–207. Masucci, M. and Passantino, A. 2016. Congenital and inherited neurologic diseases in dogs and cats: legislation and its effect on purchase in Italy. Vet. World. 9, 437–43. Morar, N., Willis-Owen, S.A., Moffatt, M.F. and Cookson, M.H. 2006. The genetics of atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118(1), 24–34. Nødtvedt, A., Egenvall, A., Bergvall, K. and Hedhammar, A. 2006. Incidence of and risk factors for atopic dermatitis in a Swedish population of insured dogs. Vet. Rec. 159(8), 241–6. Nuttall, T. 2013. The genomics revolution: will canine atopic dermatitis be predictable and preventable? Vet. Dermatol. 24(1), 10–8. Olivry, T. and Saridomichelakis, M. 2013. Evidence-based guidelines for anti-allergic drug withdrawal times before allergen-specific intradermal and IgE serological tests in dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 24(2), 225–49. Olivry, T., DeBoer, D.J., Favrot, C., Jackson, H.A., Mueller, R.S. and Nuttall, T. 2015.Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2015 updated guidelines from the International Committee on Allergic Diseases of Animals (ICADA). Vet. Res. 11, 210. Olivry, T., DeBoer, D.J., Griffin, C.E., Halliwell, R., Hiller, A., Marsella, R. and Sousa, C.A. 2001. The ACVD Task Force on Canine Atopic Dermatitis: Forewords and Lexicon. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 81(3-4), 143–6. Passantino, A. 2006. Medico-legal considerations of canine leishmaniasis in Italy: an overview of an emerging disease with reference to the purchase. Rev. Sci. Tech. 25(3), 1111–23. Passantino, A., Quartarone, V. and Russo, M. 2012. Informed consent in Italy: its ethical and legal viewpoints and its applications in veterinary medicine. A.R.B.S. 14, 16–26. Passantino. A. and De Vico, G. 2006. Our mate animals. Riv. Biol. 99, 200–4. Quartarone, V., Quartuccio, M., Cristarella, S. and Passantino, A. 2012. Technical consultation in purchase of animals: case report. Veterinaria. 26, 45–53. Rubino, R. 1972. Trattato di Diritto civile e commerciale. Milano, Italy: Giuffré editore. Santoro, D. 2019. Therapies in canine atopic dermatitis: an update. Vet. Clin. Small. Anim. 49(1), 9–26. Sousa, C.A. and Marsella, R. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (II): genetic factors. 2001. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 81(3-4), 153–7. Wilhem, S., Kovalik, M. and Favrot, C. 2011. Breed-associated phenotypes in canine atopic dermatitis. Vet. Dermatol. 22(2), 143–9. Appendix 1. Purchase agreement sample.Purchase Agreement This purchase Agreement (this “Agreement”) is entered into as of _______________________. (“ Effective date”) by and between: “Seller(s) ” ______________________________________________________, located at _______________________________________ and “Buyer(s) ” ______________________________________________________, located at _______________________________________ Each Seller and Buyer may be referred to in this Agreement individually as a “ Party” and collectively as the “ Parties”. The Parties agree as follows: Seller agrees to sell and Buyer agrees to purchase the pet described below: Species __________________________, breed____________________________________, date of birth _____________________, place of birth _____________________, gender ( )Male ( )Female, colour ________________________, transponder alphanumeric code ____________________________________, proposed use ( )family companion, ( )performance competitions, ( )conformation events or dog shows, ( )breeding, ( )other. Buyer will pay Seller for the property of the animal in question and for all obligations definited in this Agreement, if any, as the full and complete purchase price including any applicable sales tax, the sum of ___________________ (“ Purchase Price”). Buyer will be allowed to take possession of the pet on ____________________ (date). If delivery is to be made at a date after the Effective Date, it is Seller’s duty to ensure the animal is delivered in the same condition as when last inspected by Buyer. Seller represents and warrants that he/she has good and marketable title to the property and full authority to sell the animal. Seller also represents that animal is healthy and delivered accompanied by a veterinary certification indicating to the health of the animal performed by a licensed veterinarian, Dr. ________________________________ on ______________________. Seller represents and guarantees that the animal is sold free of defects, diseases that would negatively affect its health and make it unsuitable for its intended use or to impair appreciably the value. This guarantee is valid for __________ months after delivery of the animal. After this deadline and in case of completions of property deeds not explicitly agreed and authorized by the Seller that he/she will feel free from the obligations entered into with the signing of this Agreement. It is strongly recommended, that the Buyer have a licensed veterinarian examine the pet within ____ days after the buyer receives the animal. If during the warranty period, the pet appears ill, it is to be examined by a veterinarian. If the veterinarian establishes that the animal is ill and the illness was present prior to the sale, the Seller shall be contacted at once. The Seller shall (upon receipt of a statement from the examining veterinarian that the illness was present prior to the sale) pay the cost of medical care (up to, but not exceed, the purchase price of the pet). If the pet should die from a problem present prior to the sale, the Seller shall either exchange the animal with one of equal quality, or refund the purchase price. The total liability of the Seller shall in no case exceed the total sale price of this contract. The Buyer agrees to keep the animal with the diligence of the bonus pater familias and with the obligation to notify the Seller promptly any signs of discomfort of the animal. This Agreement shall be governed by and construed under the laws of the City of _______________, State of _______________, without regard to any conflict of laws principles thereof. Any dispute occurring between the parties, following to this agreement and in particular those regarding the interpretation, execution, performance, breach, termination of this contract, shall be solved through mediation. If the dispute cannot be solved, then it will be settled by an arbitration panel constituted of three members, two appointed by each party and the third by the first two arbitrators so appointed as aforesaid, and in case of disagreement by the President of the Court has territorial jurisdiction. In any case, the arbitration shall be decided in accordance with the fairness of the arbitration amicable manner without formal procedures and its decision will be conclusive. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the Parties have entered into this Agreement as of the Effective Date. SIGNATURE _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Seller Signature Seller Full Name _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Buyer Signature Buyer Full Name | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Pugliese M, Maestra RL, Previti A, Falcone A, Passantino A. Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. Open Vet J. 2022; 12(2): 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 Web Style Pugliese M, Maestra RL, Previti A, Falcone A, Passantino A. Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=121330 [Access: July 01, 2025]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Pugliese M, Maestra RL, Previti A, Falcone A, Passantino A. Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. Open Vet J. 2022; 12(2): 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Pugliese M, Maestra RL, Previti A, Falcone A, Passantino A. Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. Open Vet J. (2022), [cited July 01, 2025]; 12(2): 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 Harvard Style Pugliese, M., Maestra, . R. L., Previti, . A., Falcone, . A. & Passantino, . A. (2022) Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. Open Vet J, 12 (2), 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 Turabian Style Pugliese, Michela, Rocky La Maestra, Annalisa Previti, Annastella Falcone, and Annamaria Passantino. 2022. Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. Open Veterinary Journal, 12 (2), 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 Chicago Style Pugliese, Michela, Rocky La Maestra, Annalisa Previti, Annastella Falcone, and Annamaria Passantino. "Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians." Open Veterinary Journal 12 (2022), 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Pugliese, Michela, Rocky La Maestra, Annalisa Previti, Annastella Falcone, and Annamaria Passantino. "Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians." Open Veterinary Journal 12.2 (2022), 156-164. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Pugliese, M., Maestra, . R. L., Previti, . A., Falcone, . A. & Passantino, . A. (2022) Cases study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis from a medico-legal viewpoint. A takeaway of knowledge for practicing veterinary clinicians. Open Veterinary Journal, 12 (2), 156-164. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i2.1 |