| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(1): 395-401 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(1): 395-401 Research Article Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad cityKhalid Ismael Oleiwi1, Mohammed Ali Hussein1*, Omar Attalla Fahad1 and Sura Osamah Abdulrazzaq21Department of Internal Medicine and Preventive, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Fallujah, Al-Fallujah, Iraq 2Department of Internal Medicine and Preventive, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Fallujah, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Mohammed Ali Hussein. Department of Internal Medicine and Preventive, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Fallujah, Al-Fallujah, Iraq. Email: mohammedalani [at] uofallujah.edu.iq Submitted: 29/10/2024 Accepted: 31/12/2024 Published: 31/01/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

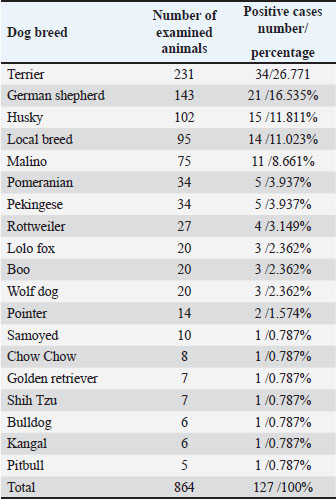

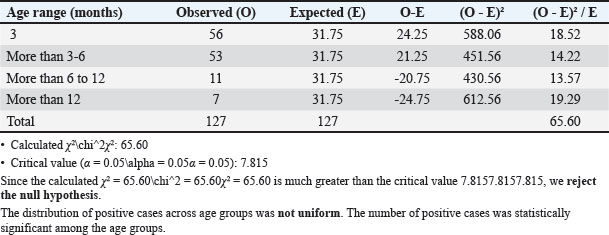

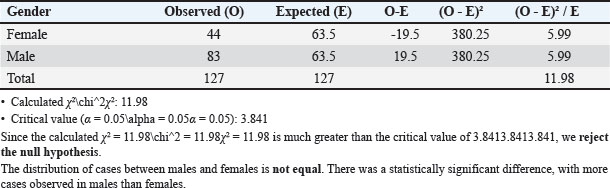

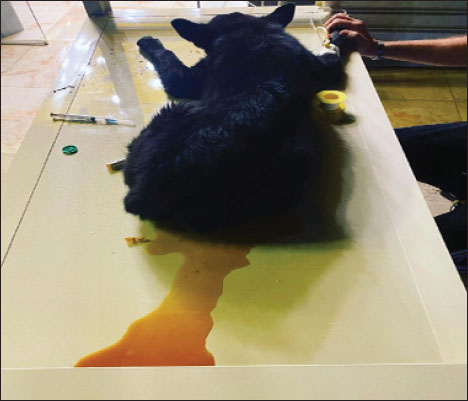

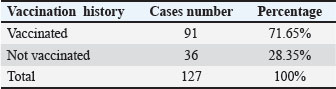

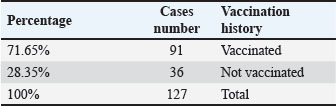

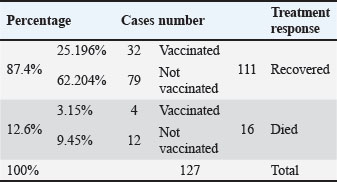

AbstractBackground: Canine parvovirus is the primary etiology of hemorrhagic diarrhea and mortality in puppies worldwide. Aim: This study was designed to investigate canine parvovirus in dogs in Baghdad by rapid testing. Methods: Rectal swabs were collected from 864 dogs presenting at sixteen private veterinary clinics with clinical signs including vomiting, anorexia, nausea, and regurgitation. All dogs were subjected to detailed clinical, physical, and laboratory investigations from early October 2021 until April 2023. Results: A total of 127 dogs were positive for parvovirus using the rapid test. The total infection rate of CPV was 14.69%, with a higher infection rate recorded in dogs less than 6 months and 3 months of age at 44.09% and 41.73%, respectively. A significant infection rate was reported in male dogs compared with female dogs, and the Terrier breed showed a higher infection rate than the other breeds included in this study. Fever was present in 78.33% of infected dogs as well as another clinical signs related to CPV infection. The infection rate was 71.65% in vaccinated dogs and 28.35% in unvaccinated dogs. After the treatment steps, 87.4% of the infected dogs recovered, and 12.6% of the infected dogs died. Conclusion: CPV is circulating in dogs in Baghdad city, and unvaccinated dogs younger than 6 months were most susceptible to the virus. Keywords: Parvovirus, Canine, Rapid test, Infection rate, Baghdad. IntroductionCanine parvovirus is a small DNA virus, which is a nonenveloped with a single-strand genome that is included in the Parvoviridae family (Mia and Hasan, 2021). There are two types of parvovirus that infect canines: CPV-1 or the minute virus of canine and CPV-2. Canine parvovirus-2 is dominant in Belgium, Japan, Australia, and the United States and is later recorded worldwide (Tuteja et al., 2022). Parvovirus is highly resistant to many disinfectants and is susceptible to halogen disinfectants, for example, sodium hypochlorite, which is commonly used for decontamination in veterinary clinics and pet animal housing facilities because of its broad-spectrum activity (Cavalli, et al., 2018). The predisposing factors to parvovirus infections in puppies are lack of protective immunity, internal parasites, unsanitary conditions, overcrowded conditions, and environmental stressful conditions (Khare, et al., 2020). Canine parvovirus infection transmitted by fecal–oral method via contact with contaminated animal feces or contaminated surfaces of infected dogs (Mia and Hasan, 2021). The winter season, small age, nonvaccination, local breed, and male sex were recorded as much higher risk factors for canine parvovirus enteritis in Bangladesh. (Nizami et al., 2020). The parvovirus infection causes high morbidity, reaching 100% in 10% of adult dogs and 90% in puppies (Pandya et al., 2017), regardless of the vaccination against canine parvovirus-2 strains; the infection remains a significant economic and veterinary concern. (Mazzaferro, 2020). The first report of canine parvovirus infection in Iraq was published in 2010 (Al-Bayati et al., 2010), and molecular detection was conducted in 2012 (Ahmed et al., 2012). This study aimed to investigate the infection rate of parvovirus disease in dogs in Baghdad, Iraq. Materials and MethodsStudy area and designDuring the period from early October 2021 to April 2023, a survey was conducted of 864 dogs in sixteen veterinary clinics located in Baghdad city, and data were collected from cases of dogs with clinical signs referred to as gastrointestinal disturbances. Data and samplesA total of 864 dogs presented to private veterinary clinics were examined with a history of vomiting, anorexia, nausea, or regurgitation and were selected and underwent detailed clinical, physical examinations and laboratory investigations. Data from every case were recorded in questionnaire including breed, age, sex, vaccination status, and details and the protocols of treatments used. A general examination was performed, including temperature, pulse, and respiration. Fecal swabs were taken to examine using the rapid monoclonal antibody test kit (Rohi Biotechnology test kit) (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria for this study of all dogs showed gastrointestinal disturbance signs and the exclusion criteria included healthy animals. ResultsThe total infection rate was found in 14.69% (127/864) of tested dogs by the rapid monoclonal antibody test (Fig. 2). Depending on the infected breeds distribution, the results showed that the infection rate of CPV in the Terrier breed was a higher percentage of infection (26.771%), while the lowest infection rate of breeds was in Samoyed, Chow, Golden retriever, Shih Tzu, Bulldog, Kangal, and Pit bull (0.787%) (Table 1). The results also revealed that a higher infection rate was recorded in dogs less than 6 months 44.09%, while a low infection rate was recorded in dogs aged more than 6 months 8.66% (Table 2); a high infection rate in canine parvovirus 48.7% has been found in dogs aged between 1 and 3 months in comparison with 4 and 6 months 17.2% and older than 6 months dogs at 8.3%. In the present study, the number of dogs with signs of canine parvovirus was significantly higher in male dogs 65.355% compared with female dogs 34.645% (Table 3). Depending on the clinical signs, 78.33% of the infected dogs experienced fever, 33.33% suffered from diarrhea, 61.66% suffered from bloody diarrhea, 58.33% suffered from vomiting, and 65% of the infected dogs suffered from dehydration (Figs. 3 and 4), (Table 4). The total infection rate of canine parvovirus in the current study was 71.65% in vaccinated dogs and 28.35% in unvaccinated dogs (Table 5). Our study also recorded that 87.4% of infected dogs recovered after treatment, and 12.6% of infected dogs died (Table 6). DiscussionThere are several ways to detect the antigen of the parvovirus in dog feces, such as using antigen rapid test kits, which enable the antibodies parvovirus specific to combine with antigens in dog feces with high accuracy (Mildbrand et al., 1984). The present results coincide with many results reported by researchers (Esfandiari and Klingeborn, 2000), and another study results reported by (Mosallanejad et al., 2008), who used the same rapid test kit that revealed high specificity and sensitivity to detect the parvovirus in Iran. Oh et al., (2006) used the kit to investigate antibodies of canine parvovirus. The results also revealed a higher infection rate in dogs less than 6 months. This finding corresponds with McCaw and Hoskins, (1997), who found that puppies aged between 6 weeks and 6 months are more susceptible to infection. These results also support the earlier reports (Nahat et al., 2015; Sen et al., 2017) that also concluded the highest canine parvovirus infection rate at 58.3% in dogs up to 6 months age group, while 11.11% infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs aged older than 18 months recorded in Bangladesh; a high infection rate of canine parvovirus 48.7% has been found in dogs aged between 1 and 3 months in comparison with 4–6 months 17.2% and older than 6 months dogs at 8.3%.

Fig. 1. Rohi Biotechnology test kit.

Fig. 2. Rapid monoclonal antibody test using fecal samples. Table 1. Distribution of positive cases according to dog breed.

The infection rate in male dogs were higher than female dogs which in lined with previous studies of Gombak et al., (2008) and Thomas et al., (2014), who recorded a significant infection rate of canine parvovirus in 78.26% of male dogs. The male sex infection preference might be because of the greater exposure chance of them to parvovirus loads by their behavior, especially roaming and territorial behavior, which is also mentioned by Deka et al., (2013). The rearing of males rather than females may be another cause of the high rate of CPV infection. The main pathogenesis of canine parvovirus infection is virus-induced rapid dividing cell destruction, involving gastrointestinal epithelial cell crypts, lymph nodes, thymus, and precursor cells of bone marrow. This leads to disruption of the intestinal mucosal barrier, atrophy of villi, and malabsorption, as well as leukopenia (especially neutropenia and / or lymphopenia), leading to vomiting, severe diarrhea, and dehydration (Kalli et al., 2010; Greene, 2012). A finding similar to our study results was also reported by Mylonakis et al. (2016) and Bhattacharjee et al. (2021). Table 2. Distribution of positive cases according to age.

Table 3. Distribution of cases according to gender.

Fig. 3. Dog suffer from bloody diarrhea.

Fig. 4. Dog suffer from dehydration, sunken eyes, and anorexia. Table 4. Distribution of positive cases according to clinical signs.

Table 5. Distribution of cases according to vaccination history.

The possible causes of the occurrence of canine parvovirus in vaccinated dogs are primary dose administration alone, delayed booster vaccination, lack of awareness regarding vaccination, and affordability of pet owners (Geetha and Selvaraju, 2021). Table 6. Distribution of recovered cases and died cases.

Decaro et al., (2020) reported that the failure of canine parvovirus disease eradication was mainly caused by immunization failures involving the presence of maternally-derived antibodies interfering titers, non-responder presence, and virus virulence. Meanwhile, the role of the canine parvovirus variants in immunization failures has been widely discussed. These treatment results resemble the results mentioned by Mylonakis et al. (2016), who reported that the recovery percentage of dogs after treatment in a veterinary hospital were (78.3%). Also Horecka et al. (2020) recorded that the overall survival rate for dogs during the 11.5-year period of study was 86.6%, with the increasing possibility of survival rate to 96.7% after 5 days of treatment. Dogs with low-weight and male sex were considered as a high risk factor for death, while age was not an important factor in the infection. Mahaprabhu et al. (2021) reported a higher rate of recovery in vaccinated dogs than in unvaccinated dogs. ConclusionIn conclusion, canine parvovirus was circulating in Baghdad city, and unvaccinated puppies younger than 6 months were mostly susceptible to the virus. Our recommendations include optimizing vaccination programs for parvovirus and identifying and treating infected dogs to reduce environmental contamination. AcknowledgmentsFor the University of Fallujah. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. FundingNo funding. Authors’ contributionsKhalid Ismael Oleiwi: Practical work. Mohammed Ali Hussein: Statistical analysis. Omar Attalla Fahad: Writing and editing. Sura Osamah Abdulrazzaq: Sampling. Data availabilityData are available upon request. ReferencesAhmed, A.F., Odisho, S.M. and Karim, A.Z. 2012. Detection of canine parvovirus in Baghdad city by PCR. In: Proceedings of the eleventh veterinary scientific conference, 95–98. Al-Bayati, H.A. Odishosh, M. and Majeed, H.A. 2010. Detection of canine parvovirus in Iraq using a rapid antigen test kit and haemagglutination –inhibition test. Al Anbar J. Vet. Sci. 3, 17–23. Bhattacharjee, PP. K. Rahman, MM. S. Sarkar, R.R. and Chakrabartty, A. 2021. Prevalence and associated risk factors of canine parvovirus and canine influenza virus infections in pet dogs in Dhaka district of Bangladesh. J. Vet. Med. OH. Res. 3(1), 119–128. Cavalli, A., Marinaro, M., Desario, C., Corrente, M., Camero, M. and Buonavoglia, C. 2018. In vitro virucidal activity of sodium hypochlorite against canine parvovirus type 2. Epi. and Inf. J. 146, 2011–2013. Decaro, N., Buonavoglia, G. and Barrs, V.R. 2020. Canine parvovirus vaccination and immunization failures: are we far from disease eradication? Vet. Micro.247:108760. Deka, D., Phukan, A. and Sarma, D.K. 2013. Epidemiology of parvovirus and coronavirus infections in dogs in Assam. Indian Vet. J. 90, 49–51. Esfandiari, J. and Klingeborn, B. 2000. A comparative study of new rapid and one– step test for the detection of parvovirus in feces from dogs, cats, and mink. J. Vet. Med. Infect. Dis., Vet. Public Hlth. 47(2): 145–153. 16. Geetha, M. and Selvaraju, G. 2023. Canine parvoviral enteritis and its determinants: an epidemiological analysis. Indian J. of animal res. 57(2): 225–230. Gombac, M., Svara, T., Tadic, M. and Pogacnic, M. 2008. Retrospective study of canine parvoviruses in Slovenia. Case Report. Slovenia Vet. Res. 45(2), 73–78. Greene, C.E. 2012. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders, pp. 67–73. Horecka, K., Poerter, S., Amirian, E.S. and Jefferson, E. 2020. A decade of treatment of canine parvovirus in animal shelters: a retrospective study. Animals J.10, 939–947. Kalli, I. Leontides, L.S. Mylonakis, M.E. Adamama-Moraitou, K. Rallis, T. and Koutinas, A.F. 2010. Factors affecting the occurrence, duration of hospitalization, and final outcome in canine parvovirus infection. Res. Vet. Sci. 89(2), 174–178. Khare, DDS. Gupta, DDK. Shukla, PPC. Das, G., Meena, N.S. and Ravi, K. 2020. Clinical and haemato-biochemical changes in canine parvovirus infection. J. Pharm. Phytochem. 9(4), 1601–1604. Mahaprabhu, R., Pazhanivel, N., Rao, G.V., Raj, G.D. and Parthiban, M. 2021. Prevalence of canine parvoviral enteritis in vaccinated and unvaccinated puppies in and around Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Pharm. Innov. J. 10(9), 560–563. Mazzaferro, E.M. 2020. Update on canine parvoviral enteritis. Small Anim. 50, 1307–1325 McCaw, D.L. and Hoskins, J.D. 2006. Canine viral enteritis. In: Green CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders, pp. 63–73. Mia, M.M. and Hasan, M. 2021. Update on canine parvovirus infection: a review from the literature. Vet. Sci. Res. J. 7(2), 92–100. Mildbrand, M.M., Teramoto, Y.A., Collins, J.K., Mathys, A. and Winstin, S. 1984. Rapid detection of Canine parvovirus in feces using monoclonal antibodies and enzyme. link immuno sorbent assay. Am J. Vet. Res., 45 (11): 2281–2284. 15. Mosallanejad, B., Najaf abadi, G.M. and Avizeh, R. 2008. The first report of concurrent detection of canine parvovirus and coronavirus in diarrheic dogs of Iran. Iranian J. Vet. Res., 9(3), 284–286. 17. Mylonakis, M., Kalli, I. and Rallis, T. 2016. Canine parvoviral enteritis: an update on the clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Vet. Med. Res. Rep. 7, 91–100. Nahat, F.W., Rahman, M.S., Sarker, R., Hasan, M.K., Hasan, A.K., Akter, L and Islam, M.A. 2015. Prevalence of canine parvo virus infection in street dogs using a rapid antigen detection kit. Res. in Agr. Livestock and Fisheries 2, 459–464. Nizami, T.A., Al-Sattar, A., Akter, S., Rahman, M.H., Chisty, N.N., Chowdhury, M.Y.E. and Hoque, M.A. 2020. Epidemiological inspection of canine parvoviral enteritis at a teaching veterinary hospital in Chattogram, Bangladesh. Turkish Vet. J. 2, 45–53. Oh, J., Ha, G., Cho, Y., Kim, M., An, D. J., Hwang, K., Lim, Y., Park, B., Kang, B. and Song, D. 2006. One-step immune chromatography assay kit for detecting canine parvovirus antibodies. Clin. Vacc. Immunol. 13(4), 520–524. Pandya, M.S., Sharma, K.K., Kalyani, H.I. and Sakhare, S.P. 2017. Study on host predisposing factors and diagnostic tests for canine parvovirus (CPV-2) infection in dogs. J. Anim. Res. 7: 897–902. Qi, S. Zhao, J., Guo, D. and Sun, D. 2020. A mini review of the epidemiology of canine parvovirus in China. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 5. Sen S.R., Nag M., Rahman M.M., Sarker R.R. and Kabir S. 2016. Prevalence of canine parvo virus and canine influenza virus infection in dogs in Dhaka, Mymensingh, Feni, and Chittagong districts of Bangladesh. Asian J. of Med. and Bio. Res. 2, 138–142. Thomas, J., Singh, M., Goswami, T.K., Verma, South and Badasara, S.K. 2014. Polymerase chain reaction-based epidemiological investigation of canine parvoviral disease in dogs at Bareilly region. Vet. World. 7(11), 929–932. Tuteja, D., Banu, K. and Mondal, B. 2022. Canine arbovirology: a brief updated review on structural biology, occurrence, pathogenesis, clinical diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 82, 101765. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Oleiwi KI, Hussein MA, Fahad OA, Abdulrazzaq SO. Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(1): 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 Web Style Oleiwi KI, Hussein MA, Fahad OA, Abdulrazzaq SO. Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=226552 [Access: January 15, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Oleiwi KI, Hussein MA, Fahad OA, Abdulrazzaq SO. Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(1): 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Oleiwi KI, Hussein MA, Fahad OA, Abdulrazzaq SO. Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 15, 2026]; 15(1): 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 Harvard Style Oleiwi, K. I., Hussein, . M. A., Fahad, . O. A. & Abdulrazzaq, . S. O. (2025) Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. Open Vet. J., 15 (1), 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 Turabian Style Oleiwi, Khalid Ismael, Mohammed Ali Hussein, Omar Attalla Fahad, and Sura Osamah Abdulrazzaq. 2025. Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (1), 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 Chicago Style Oleiwi, Khalid Ismael, Mohammed Ali Hussein, Omar Attalla Fahad, and Sura Osamah Abdulrazzaq. "Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Oleiwi, Khalid Ismael, Mohammed Ali Hussein, Omar Attalla Fahad, and Sura Osamah Abdulrazzaq. "Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city." Open Veterinary Journal 15.1 (2025), 395-401. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Oleiwi, K. I., Hussein, . M. A., Fahad, . O. A. & Abdulrazzaq, . S. O. (2025) Infection rate of canine parvovirus in dogs presented at private veterinary clinics in Baghdad city. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (1), 395-401. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.35 |