| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2408-2415 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2408-2415 Research Article Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, IraqLina Saheed Waheed1 and Mawlood Abbas Al-Graibawi2*1Internal and Preventive Veterinary Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Al-Qasim Green University, Babylon, Iraq 2Internal and Preventive Veterinary Medicine College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Mawlood Abbas Al-Graibawi. Internal and Preventive Veterinary Medicine College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq. Email: graibawi-57 [at] covm.uobaghdad.edu.iq Submitted: 13/01/2025 Revised: 15/05/2025 Accepted: 28/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

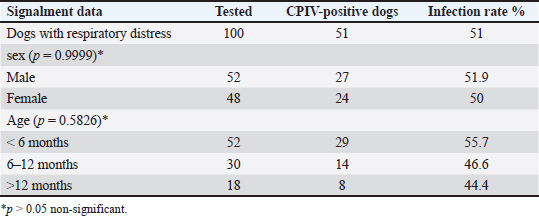

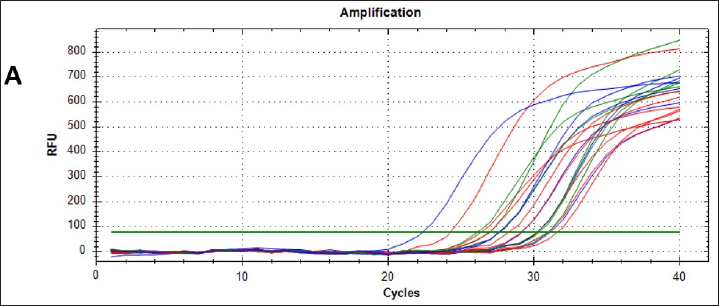

AbstractBackground: This study aimed to detect canine parainfluenza virus-5 (CPIV-5) in dogs in Baghdad city, using reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and conventional nested (RT-nPCR) techniques, along with phylogenetic analysis. Methods: Nasal swabs were obtained from 150 dogs, (100 sick dogs showing respiratory distress and 50 apparently healthy dogs), from January 2023 to April 2024. Results: CPIV-5 was detected by RT-qPCR in 51 out of 100 sick dogs (51%) and 17 out of 50 apparently healthy dogs (34%). All positive RT-qPCR samples were rechecked by RT-nPCR. Ten final RT-nPCR products were sequenced, and the data were deposited in NCBI Gene Bank. These samples were categorized as CPIV-5 based on nucleocapsid protein gene analysis. The phylogenetic analysis based on amino acids revealed that local strains were distinct, with the first cluster sharing identity and similarity scores with international isolates, while the second cluster differed significantly from international isolates and could be Iraqi strains. Conclusion: This study concluded for the first time on the presence of CPIV-5 in both sick and apparently healthy dogs. The latter could act as reservoirs of the virus, contributing to the transmission of the disease to susceptible dogs, ultimately leading to increased morbidity. Keywords: CPIV-5, RT-qPCR, Nested RT-PCR, Phylogenetic analysis, Iraq. IntroductionCanine parainfluenza virus 5 (CPIV-5) whose scientific denomination, according to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Virus, is Mammalian orthorubulavirus 5 and is classified in the Mononegavirales order, Paramyxoviridae family, and the Orthorubulavirus genus (Rima et al., 2019) that poses a major threat to mammal and human health (Zhou et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). It is a significant viral pathogen in dogs, widely distributed and impacted as a primary pathogen in canine infectious respiratory disease (CIRD) or “kennel cough,” causing secondary pneumonia (Cheng et al., 2023; Yang, et al., 2022). The virus is transmitted through aerosols, causing respiratory diseases and lesions in the nasal mucosa, pharynx, trachea, and bronchi with petechial hemorrhages in the lungs, the incubation period is usually 2–10 days, with clinical signs such as harsh cough for 2–6 days, nasal discharge, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and sometimes fever (Reagan and Sykes, 2020; Sykes, 2022; Cordisco et al., 2022). The diagnosis is dependent on the detection of the virus in the throat and nasal secretions by RT-PCR method, the determination of a rising antibody level by enzyme- linked immunosorbent assay, and hemagglutination inhibition, whereas virus neutralization test is a useful method (Reagan and Sykes, 2020; Yang et al., 2024). Molecular reactions are used as quick and sensitive diagnostic tools for respiratory virus infections in humans and animals (Salah et al., 2020; AL-Mutar, 2020; Al-Saadi, 2020; Al-Hussaniy et al., 2022). RT- qPCR assays are costly but offer high sensitivity and specificity, saving time, and preventing contamination, particularly in CPIV-5 in CIRD-affected samples (Arya, 2005; Bustin et al., 2009; Kralik and Ricchi, 2017). Previously, RT-nested PCR (RT-nPCR) assays were used to detect CPIV-5 and for surveillance in CIRD-affected or healthy dogs (Erles et al., 2004; Hiebl et al., 2019; Charoenkul et al., 2021). In Iraq, various canine diseases have been researched (Faraj, 2019; Badawi and Yousif, 2020; Mansour and Hasso, 2021; Al-Mosoy et al., 2022; Hussein and Al-Graibawi, 2024; Jbr and Jumaa, 2024) with no previous studies on CPIV-5. So, this study was designed to investigate the virus in dogs in Baghdad city. Moreover, understanding CPIV-5 epidemiology is essential for developing effective diagnostic strategies, therapeutic, and vaccination or monitoring programs. We assume that the current study posits that addressing these gaps through rigorous investigation will enhance knowledge of CPIV-5 impact on canine health. This study represents a vital step toward filling the existing knowledge void regarding CPIV-5 in Iraq and may inform future research directions and veterinary practices. So, this study aimed to detect CPIV-5 in Baghdad province using RT-qPCR and RT-nPCR techniques with phylogenetic analysis. Materials and MethodsOne hundred and fifty nasal swab samples were collected from (100 sick dogs showing respiratory distress and 50 apparently healthy dogs) which were randomly selected from Baghdad Veterinary Hospital and private veterinary clinics in Baghdad City, Iraq, from January 2023 to March 2024. Their ages ranged from 1 month to 12 years. Demographic data for the animals, including detailed clinical examination, sex, age, breed, being housed in groups or individually, and history of vaccination, were recorded (Reagan and Sykes, 2020). Nasal swabs were kept in viral transport media tubes in a cooled box using ice bags, transferred to the laboratory, and then stored in liquid nitrogen after transferring the media into cryotubes. RNA extraction was performed using a viral nucleic acid extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ADDBio, Korea) and performing complementary DNA (cDNA), which was kept frozen at –20°C until the RT-nPCR test was performed. cDNA was synthesized with the commercial kit (ADDBio, Korea) as instructed by the manufacturer. Molecular detection of CPIV-5 was conducted using RT-qPCR with primers and AddScript RT-qPCR SYBER master (AddBio, Korea)-based assay, and the reaction included H2o 6 μl, AddScript RT-qPCR 10 μl, and 0.05 pmol/20 μl for each primer was add, the forward primer was AGTTTGGGCAATTTTTCGTCC, and the reverse primer was TGCAGGAGATATCTCGGGTTG and cDNA 2 μl (Hiebl et al., 2019). Thermal conditions involved activation at 50ºC for 2 minutes, initial denaturation at 95ºC for 10 minutes, denaturation at 95ºC for 15 seconds, followed by annealing at 56.3ºC for 30 seconds, and extension at 72ºC for 35 seconds. For sequencing, all positive samples were checked by conventional RT-nPCR targeting a 182 bp fragment of the nucleocapsid protein (NP) gene of CPIV-5, the oligonucleotides used in this study (PNP1 AGTTTGGGCAATTTTTCGTCC, PNP2 TGCAGGAGATATCTCGGGTTG, PNP3 TGCAGGAGATATCTCGGGTTG, PNP4 GCAGTCATGCACTTGCAAGTCACTA) were designed previously (Erles et al., 2004). In the total reaction volume of the first round, 20 μl contained 2 μl of each primer, forward primer (PNP1), and reverse primer (PNP2). Taq Master containing PCR master mix (AddBio) 10 μl, cDNA 3 μl and completed the volume of the reaction to 20 μl with distilled water. In the second round, the total reaction volume of 20 μl contained PCR master mix (AddBio) 10 μl, 1 μl of each primer, forward primer (PNP3) and reverse primer (PNP4), and 1 μl of the product from the first round. Thermal conditions included initial denaturation at 95ºC for 2 minutes, followed by denaturation at 95ºC for 35 seconds, annealing at 55ºC for 30 seconds, extension at 72ºC for 40 seconds, and final extension at 72ºC for 5 minutes in both rounds of RT-nPCR. The samples were sent to Macrogen, South Korea, to conduct PCR sequencing by the Sanger technique after purifying the PCR products. A partial gene sequence of NP was targeted. After obtaining the sequence results, they were trimmed from noise signals and submitted to NCBI BLAST for obtaining relevant accession numbers. Statistical analysisThe chi-square analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used for analysis results, employing version 27 of IBM’s statistical package for social sciences (SPSS), and p-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant (Bluman, 2017). Ethical approvalThe current study was certified by the committee of Ethics in the College of Veterinary Medicine/ Baghdad University (No. P.G/199 on 5/1/2023). ResultsClinical signsThe first clinical manifestations and molecular findings of CPIV-5 in dogs in Iraq were stated by the current study; the results of the clinical examination of the infected dogs revealed that there were fevers up to 40°C, serous watery to purulent nasal discharge, inappetence, dry hacking cough, lacrimation, abnormal breath sounds, and in some severe cases open-mouthed breathing in 11 0ut off 100 dogs (11%) with respiratory signs. Molecular diagnosisThe CPIV-5 was detected by RT-qPCR in 51 out of 100 dogs (51%) with respiratory signs and 17 out of 50 apparently healthy dogs (34%) in Baghdad city. There was no significant difference between sex, age, and CPIV-5 infection in sick dogs (Table 1). The results of the real-time PCR amplification plot of NP gene CPIV-5 positive samples from dogs were detected by the (22–31) cycles, and no samples showed a curve under 40 cycles when the template concentration is high and amplification was observed during early heating cycles, as shown in Figure 1 Table 1. Canine parainfluenza virus-5 infection rate in dogs with respiratory distress by RT-qPCR.

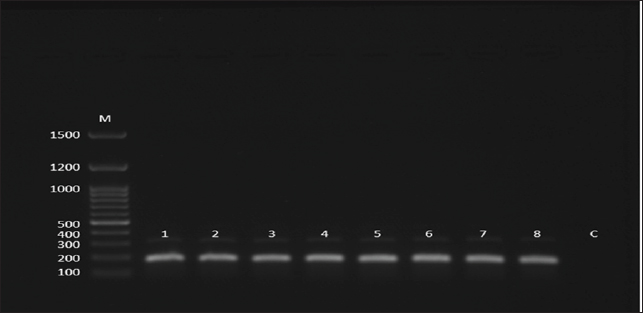

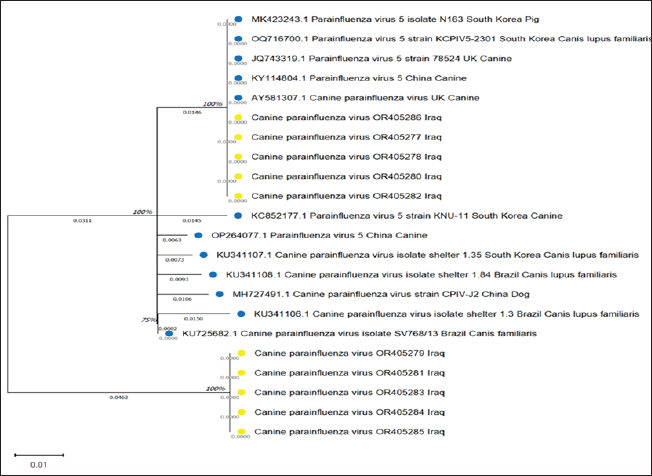

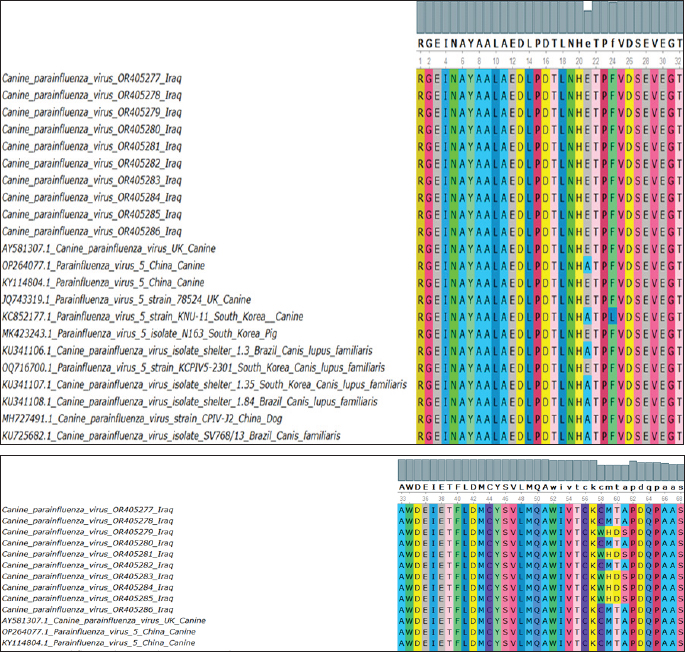

Fig. 1. Real-time qPCR amplification plot of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in nasal swab samples from sick dogs, the reaction started at 22, 24, 26, 28, and 31, respectively. All RT-qPCR-positive samples were confirmed by RT-nPCR. The positive samples were categorized as CPIV-5 type based on NP gene analysis (Fig. 2). Ten final RT-nPCR products were sequenced, and BLAST outcomes were documented in the NCBI Gene Bank (National Centre for Biotechnology Information). The nucleotide sequences generated in our study were deposited in GenBank. These isolates are indicated as: OR405277.1, OR405278.1, OR405279.1, OR405280.1, OR405281.1, OR405282.1, OR405283.1, OR405284.1, OR405285.1, and OR405286.1. The phylogenetic tree shows the genetic relation of CPIV-5 isolates obtained from Iraq, South Korea, China, Brazil, and the UK. These isolates are indicated as OR405286, OR405278, OR405277, OR405280, OR405282 among others, and belong to the Iraqi CPIV- 5 strain; hence, their similarity is apparent from the cluster formation. This clustering gives an indication of the relatedness of the Iraqi isolates, indicating either local transmission or little genetic variation occurring within this region of the world. The isolates from South Korea, China, and Brazil are in different clades indicating geographical and genetic differences from the Iraqi strains. Notably, the South Korean and Chinese canine isolates clustering with each other are more closely related to each other than to those of the Iraq isolates, suggesting different evolutionary lineages according to geographical location (Fig. 3). The changes were found in amino acid 58, 59, 60,61 C→W, M→H, T→ D and A→ S (Fig. 4). Bootstrap values have been shown on the tree and there are some branches that are supported by 100% which add more statistical support to the indicated grouping and the observed genetic clustering. Different values such as 0.0046 and 0.0106 shown beside the branch indicate genetic distance; short branches between isolates are optimistic for bare minimum variation among isolates, and it is in the case of Iraqi isolates.

Fig. 2. Gel electrophoresis image (agarose 1.5 %) shows amplicons of CPIV-5 lanes 1–8 (size = 182 bp) by the conventional nested PCR. M: 100–1500 bp DNA molecular marker (Genedirex, South Korea); C is control negative in which similar PCR components were used except H2O was added instead of DNA.

Fig. 3. Evolutionary analysis by maximum likelihood method was inferred for the identified canine parainfluenza virus in Iraq (referred to with yellow circles) followed by the obtained accession numbers (translated into their relevant amino acids). These were compared with other global sequences (referred to with blue circles) and their relevant strains. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site (below the branches). This analysis involved 22 amino acid sequences. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA11 (Tamura et al., 2021).

Fig. 4. Multiple sequence alignment of the identified sequences translated into their relevant amino acids. These were compared with other global sequences to show the differences and similarities. Branch length: The branch length, represented by values such as 0.0046 and 0.0106, indicates the level of genetic divergence between isolates, lesser branches among the Iraqi isolates signify little genetic Further, there is a separate group of sequences from South Korea and Brazil (KU341107.1, KU341106.1) which appears to be genetically divergent from both the Iraqi and rest of the isolates due to the evolutionary divergence or variation in viral dynamics in these countries. DiscussionThe CPIV-5 is an extremely contagious pathogen and produces mild to moderate respiratory infections in dogs widespread, coinfection with other viruses and pathogens can cause severe clinical signs (Cheng et al., 2023; Zhou, et al., 2024). Clinical diagnosis is based on case history, clinical signs, and response to therapy, the results of clinical examination of the dogs in the current study correlated with other results, and they showed clinical signs including paroxysmal harsh cough for 2–6 days, serous nasal discharge, conjunctivitis, retching, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, with or without pyrexia, lacrimation, depression, and dyspnea (Reagan and Sykes, 2020; Cordisco et al., 2022). This pathogen invades the epithelial cells of the respiratory system and affects the cilia and alveolar macrophage predisposing to lower respiratory tract disease (bronchitis, pneumonia) that is usually associated with secondary bacterial infections, such as Bordetella bronchiseptica infections (Sykes, 2022). The present study confirmed that this virus is present in symptomatic and apparently healthy dogs. The highest positivity rate appeared in sick animal samples. Similar to our results, numerous studies recorded that the CPIV-5 detected in healthy and sick dogs and shown to be significantly higher if dogs had respiratory distress; the infection rate was 5.6%–67.5% of dogs with canine infectious respiratory disease or bronchial pneumonia (Schulz et al., 2014; Hiebl et al., 2019; Day et al., 2020; Charoenkul et al., 2021). Moreover, the high infection rate with CPIV-5 in symptomatic dogs similar to numerous other studies mentioned that CPIV-5 is highly contagious and excreted from the respiratory secretions of acutely infected dogs and therefore endemic worldwide (Viitanen et al., 2015; Decaro et al., 2016; Kaczorek et al., 2017). Damian et al. (2005) detected CPIV-5 in 18 of 35 (51%) cases of dogs that died from acute or subacute pneumonia in Mexico in 2004. The study findings were higher than other results for detection of CPIV-5 in other countries, Rahmani et al. (2016) reported that the infection rates of CPIV-5 in healthy and dogs with respiratory signs were 13.33% and 20%, respectively, in Iran. Mochizuki et al. (2008) mentioned that the CPIV-5 had with highest rates of 7.4% among other viruses detected in 68 household dogs with respiratory clinical signs. In England, Erles et al. (2004) revealed that by RT-PCR, CPIV-5 was detected in 33 out of 170 (19.4%) tracheal samples and 11 out of 106 (10.4%) lung samples tested. CPIV- 5 RNA was detected in tracheal samples from dogs with all grades of CIRD as well as in samples from dogs without clinical symptoms. It was most frequently found in dogs suffering from mild respiratory disease. Lung samples were rarely found positive for CPIV- 5 RNA, and the positive samples were mostly from dogs without clinical respiratory disease. The virus is present in a high percentage in Iraq’s ecosystem due to environmental or socio-economic factors (e.g., lack of vaccination), exposure of the animals to stress factors, geographical aspects, such as climate, that could affect the virus transmission, and lack of well- care for animals. In the current research, a greater number of positive samples were found in puppies with respiratory signs under 6 months compared to other dogs (6–12 months, >12 months); this could be attributed to the vulnerability of young dogs to contagious viruses due to the lack of previous contact and an undeveloped immune system (Mochizuki et al., 2008; Mosallanejad et al., 2009). This observation is in covenant with earlier research mentioned that CPIV- 5 could be observed more in younger dogs than in dogs in other age groups and there was no statically significant modification among dog’s age categories in their sensitivity to CPIV-5 (Mochizuki et al., 2008; Rahmani et al., 2016). The phylogenetic trees for the Iraqi CPIV-5 isolates indicated that these samples cluster within the local region through a low degree of genetic variation. On the other hand, isolates from South Korea (Yondo et al., 2023), Brazil (Daian e Silva et al., 2023), and China (Cheng et al., 2023) were clustered separately, which may be a result of different evolution process. That gives an indication of the relatedness of the Iraqi isolates; indicating either local transmission or little genetic variation occurring within this region of the world. ConclusionBased on our data, CPIV-5 is a common disease in dogs in Baghdad city. It was detected in both dogs with respiratory signs and apparently healthy dogs. In addition, the genetic findings indicated that five local isolates are originally different from the international isolates and could be Iraqi strains where the vaccine can be manufactured from these local strains to reduce the spread of CPIV-5. We recommended more surveys of the virus prevalence and studying potential co- infections in Iraq. AcknowledgmentsWe are grateful to the College of Veterinary Medicine— University of Baghdad and Al-Qasim Green University for their support in providing tools, samples, and a situation for the experiment. Conflict of interestNone. Funding StatementsThe authors declare that the present study has no financial issues to disclose. Authors contributionsLina Shaheed Waheed: Practical work. Mawlood Abbas Ali Al-Graibawi: study design and editing. ReferencesAl-Hussaniy, H.A., Altalebi, R.R., Albu-Rghaif, A.H. and Abdul-Amir, A.G.A. 2022. The use of PCR for respiratory virus detection on the diagnosis and treatment decision of respiratory tract infections in Iraq. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 16(1), 201–206. Al-Mosoy, A.S., Tamimi, N.S. and Alwan, W.N. 2022. Clinical complications for canine parvovirus infection in puppies. Biochem. and Cell. Arch. 22(2), 3827. Al-Mutar, H.A. 2020. The evolution of genetic molecular map and phylogenetic tree of Coronavirus (COVID-19). Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 44(2), 56–70. Al-Saadi, M.H. 2020. Development of in-house Taqman qPCR assay to detect equine herpesvirus-2 in Al- Qadisiyah city. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 34(2), 356–371. Arya, M., Shergill, I.S., Williamson, M., Gommersall, L., Arya, N. and Patel, H.R. 2005. Basic principles of real-time quantitative PCR. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 5(2), 209–219. Badawi, N.M. and Yousif, A.A. 2020. Survey and molecular study of Babesia gibsoni in dogs of Baghdad province, Iraq. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 44(E0), 34–41. Bluman, A.G. 2017. Elementary statistics: a step by step approach for MATH 10. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education. Bustin, S.A., Benes V., Garson J.A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., Mueller R., Nolan T., Pfaffl M.W., Shipley G.L., Vandesompele J. and Wittwer C.T. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55(4), 611–622. Charoenkul, K., Nasamran, C., Janetanakit, T., Chaiyawong, S., Bunpapong, N., Boonyapisitsopa, S., Tangwangvivat, R. and Amonsin A. 2021. Molecular detection and whole genome characterization of canine parainfluenza type 5 in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3866. Cheng, H., Zhang, H., Cai, H., Liu, M., Wen, S. and Ren, J. 2023. Molecular biology of canine parainfluenza virus V protein and its potential applications in tumor immunotherapy. Front. Microb. 14, 1282112. Cordisco, M., Lucente, M.S., Sposato, A., Cardone, R., Pellegrini, F., Franchini, D., Di Bello, A. and Ciccarelli, S. 2022. Canine parainfluenza virus infection in a dog with acute respiratory disease. Vet. Sci. 9(7), 346. Damián, M., Morales, E., Salas, G. and Trigo, F.J. 2005. Immunohistochemical detection of antigens of distemper, adenovirus and parainfluenza viruses in domestic dogs with pneumonia. J. Comp. Pathol. 133(4), 289–293. Day, M.J., Carey, S., Clercx, C., Kohn, B., MarsilIo, F., Thiry, E., Freyburger, L., Schulz, B. and Walker, D.J. 2020. Aetiology of canine infectious respiratory disease complex and prevalence of its pathogens in Europe. J. Comp. Path. 176, 86–108. Decaro, N., Mari, V., Larocca, V., Losurdo, M., Lanave, G., Lucente, M.S. and Buonavoglia, C. 2016. Molecular surveillance of traditional and emerging pathogens associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 192, 21–25. Erles, K., Dubovi, E.J., Brooks, H.W. and Brownlie, J. 2004. Longitudinal study of viruses associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42(10), 4524–4529. Daian e Silva, D.S.O., Pinho, T.M.G., Rocha, R.P., Oliveira, S.B., Franco, G.M., Barbosa-Stancioli, E.F. and Da Fonseca, F.G. 2023. Preclinical evaluation of a recombinant MVA expressing the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase envelope protein of parainfluenza virus 5 (Mammalian orthorubulavirus 5). Vet. Vac. 2(2), 100027. Faraj, A.A. 2019. Traditional and molecular study of Cryptosoporidium spp. in domestic dogs in Baghdad city, Iraq. Iraqi J. Agricul. Sci. 50(4) Iraqi J. Agricul. Sci. 50(4), 1094–1099. Hiebl, A., Auer, A., Bagrinovschi, G., Stejskal, M., Hirt R., Rümenapf, H.T., Tichy, A. and Künzel, F. 2019. Detection of selected viral pathogens in dogs with canine infectious respiratory disease in Austria. J. Small Anim. Pract. 60(10), 594–600. Hussein, M.A. and Al-Graibawi, M.A.A. 2024. Clinical and molecular study of Canine Enteric Coronavirus in Iraq. Egyp J. Ve. Sci. 55(5), 1357–1363. Jbr, A. and Jumaa, R. 2024. Sequencing analysis of the N gene of canine distemper virus from infected dogs in Baghdad City. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 48(1), 41–47. Kaczorek, E., Schulz, P., Małaczewska, J., Wójcik, R., Siwicki, A.K., Stopyra, A. and Mikulska-Skupień, E. 2017. Prevalence of respiratory pathogens detected in dogs with kennel cough in Poland. Acta Vet. Brno. 85(4), 329–336. Kralik, P. and Ricchi, M. 2017. A basic guide to real time PCR in microbial diagnostics: definitions, parameters, and everything. Front. Microbiol. 8, 108. Mansour, K.A. and Hasso, S.A. 2021. Molecular detection of canine distemper virus in dogs in Baghdad Province, Iraq. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 45(2), 46–50. Mochizuki, M., Yachi, A., Ohshima, T., Ohuchi, A. and Ishida, T. 2008. Etiologic study of upper respiratory infections of household dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 70(6), 563–569. Mosallanejad, B., Avizeh, R., Seyfiabad, S.M. and Ramesh, B. 2009. Antigenic detection of Canine parainfluenza virus in urban dogs with respiratory disease in Ahvaz area, southwestern Iran. Arch. Razi. Instit. 64(2), 115–120. Rahmani, Y., Hasiri M.A. and Mohammadi, A. 2016. Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus circulation among home-owned dogs in Shiraz, Iran. Bulga J. Vet. Med. 19, 40–46. Reagan, K.L. and Sykes, J.E. 2020. Canine infectious respiratory disease. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 50(2), 405. Rima B., Balkema-Buschmann A., Dundon, W.G., Duprex, P., Easton, A., Fouchier, R., Kurath, G., Lamb, R., Lee, B., Rota, P., Wang, L., Ictv Report Consortium. 2019. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Paramyxoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 100(12), 1593–1594. Salah, H.A., Fadhil, H.Y. and Alhamdani, F.G. 2020. Multiplex sybr green assay for coronavirus detection using fast real-time rt-pcr. Iraqi J. Agricul. Sci. 51(2), 556–564. Schulz, B.S., Kurz, S., Weber, K., Balzer, H.J. and Hartmann, K. 2014. Detection of respiratory viruses and Bordetella bronchiseptica in dogs with acute respiratory tract infections. Vet. J. 201(3), 365–369. Sykes, J.E. 2022. Greene’s infectious diseases of the dog and cat-E-Book. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences. Tamura, K., Stecher, G. and Kumar, S. 2021. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(7), 3022–3027. Viitanen S.J., Lappalainen, A. and Rajamäki, M.M. 2015. Co-infections with respiratory viruses in dogs with bacterial pneumonia. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29(2), 544–551. Yang, D.K., Kim, H.H., Lee, H.J., Cheong, Y.J., Hyeon, L.S., Kim M. and Hyun, B.H. 2024. Incidence of canine viral diseases and prevalence of virus neutralization antibodies of canine distemper virus, adenovirus type 2, parvovirus, and parainfluenza virus type 5 in Korean dogs. Korean J. Vet. Res. 64(1), e3. Yang, M., Ma, Y., Jiang, Q., Song, M., Kang, H., Liu, J. and Qu, L. 2022. Isolation, identification and pathogenic characteristics of tick-derived parainfluenza virus 5 in Northeast China. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 69(6), 3300–3316. Yondo, A., Kalantari, A.A., Fernandez-Marrero, I., McKinney, A., Naikare, H.K. and Velayudhan, B.T. 2023. Predominance of canine parainfluenza virus and Mycoplasma in canine infectious respiratory disease complex in dogs. Pathogens, 12(11), 1356. Zhou, N., Chen, L., Wang, C., Lv, M., Shan, F., Li, W., Wu, Y., Du, X., Fan, J., Liu, M., Shi, M., Cao, J., Zhai, J. and Chen, W. 2024. Isolation, genome analysis and comparison of a novel parainfluenza virus 5 from a Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris). Front. Vet. Sci. 11, 1356378. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Waheed LS, Al-graibawi MA. Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 Web Style Waheed LS, Al-graibawi MA. Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=237503 [Access: December 10, 2025]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Waheed LS, Al-graibawi MA. Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Waheed LS, Al-graibawi MA. Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited December 10, 2025]; 15(6): 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 Harvard Style Waheed, L. S. & Al-graibawi, . M. A. (2025) Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 Turabian Style Waheed, Lina Saheed, and Mawlood Abbas Al-graibawi. 2025. Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 Chicago Style Waheed, Lina Saheed, and Mawlood Abbas Al-graibawi. "Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Waheed, Lina Saheed, and Mawlood Abbas Al-graibawi. "Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2408-2415. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Waheed, L. S. & Al-graibawi, . M. A. (2025) Molecular detection of canine parainfluenza virus-5 in dogs in Baghdad province, Iraq. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2408-2415. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.13 |