| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2427-2438 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2427-2438 Research Article Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102Ga-Yeong Lee1, Hae-Yeon Cho1, Syed Al Jawad Sayem1, Seung-Joon Kim1, Md Sekendar Ali1 and Seung-Chun Park1,2*1Institute for Veterinary Biomedical Science, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea 2Cardiovascular Research Institute, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea * Corresponding Author: Seung-Chun Park. College of Veterinary Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, South Korea. Email: parksch [at] knu.ac.kr Submitted: 14/01/2025 Revised: 05/05/2025 Accepted: 16/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

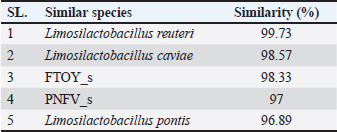

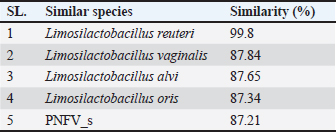

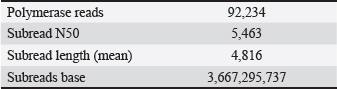

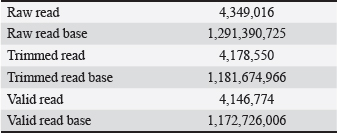

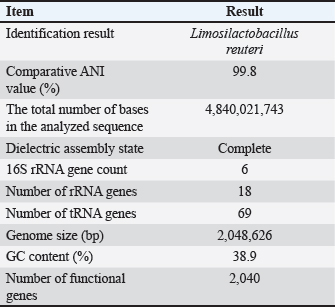

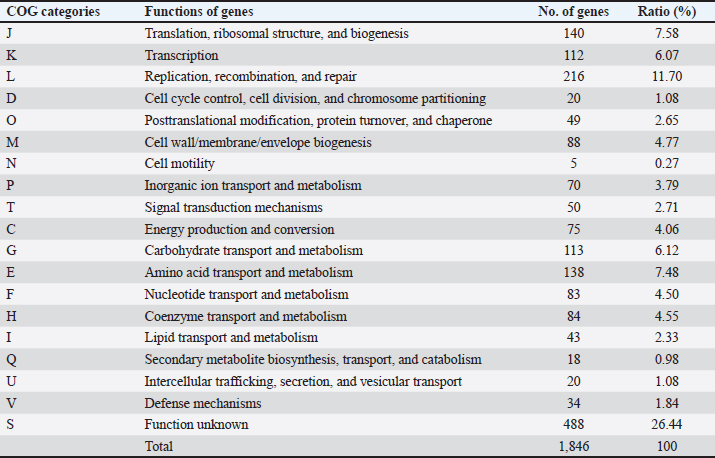

AbstractBackground: Gut microbiota are potential sources of probiotics and play an essential role in maintaining intestinal health. Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 (L. reuteri PSC102), which was isolated from the feces of healthy pigs, exhibited health-beneficial properties. Aim: We aimed to conduct a whole-genome sequencing analysis of L. reuteri PSC102 to determine its molecular characteristics as a probiotic strain. Methods: Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 cells were cultured in De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe medium, followed by DNA extraction for genomic analysis using the PacBio–Illumina sequencing platform. The EzBioCloud software was used to perform gene assembly, and the genes were interpreted by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and the Glimmer program. Core and pan-genomic analyses were performed to assess the extent of functional conservation in the genomic sequence. Moreover, the NCBI database and the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool software were used to identify antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors. Results: Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 consists of a single circular chromosome with 2,048,626 bp, a guanine- cytosine of 38.9%, 18 rRNA genes, and 69 tRNA genes. Among the 1,846 protein-coding sequences, genes associated with probiotic characteristics were identified, including genes involved in host-microbe interactions, stress tolerance, biogenesis, and defense mechanisms. Furthermore, the genome of L. reuteri PSC102 comprises 2,446 pan-genome and 1,222 core-genome orthologous gene clusters. A total of 74 unique genes were identified in L. reuteri PSC102 genome. These genes mostly encode proteins potentially involved in the transport and metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates. Moreover, antibacterial resistance genes and virulence factors were absent in L. reuteri PSC102. Conclusion: The results of the molecular insight into L. reuteri PSC102 corroborates its use as a probiotic in humans and other animals. Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance genes, Genomic feature, Phylogenetic tree, Probiotic, Virulence genes. IntroductionThe mammalian body possesses inherent defense mechanisms that safeguard against potentially detrimental microorganisms, encompassing the intestinal epithelium’s physical and chemical barriers (Yakout and Eckhardt, 2022). The intestinal epithelium is a physical barrier that protects the host against harmful microorganisms. Additionally, the intestinal mucosa, which is covered with a layer of mucus, aids in the elimination of pathogens from the gastrointestinal tract (Martens et al., 2018). The gut is also regarded as a reservoir of different beneficial bacteria, contributing to the potential source of probiotics. These bacteria possess several beneficial characteristics, including the production of digestive enzymes and antioxidant and antibacterial activities (Ali et al., 2023b). Moreover, probiotics can survive in bile salts and gastric acids, allowing other helpful bacteria to proliferate in the gastrointestinal tract (Ali et al., 2023b). Probiotics can regulate the abundance of enteric pathogens by producing antimicrobial compounds, such as bacteriocin. Reuterin, a well-known bacteriocin secreted by the commensal Limosilactobacillus reuteri in the gut, inhibits different enteropathogens, including protozoa, yeast, viruses, and fungi, and stimulates beneficial bacterial growth (Liu et al., 2020). Asare et al. (2020) showed that reuterin obtained from L. reuteri PTA5_F13 demonstrates powerful antimicrobial activity against a broad panel of pathogenic Campylobacter spp. Moreover, probiotics can synthesize organic acid metabolites, specifically short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which impede the growth of pathogens by effectively reducing the local pH (Lamas et al., 2019). Furthermore, these microbiota can regulate the expression of virulence genes in certain pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli (Kamada et al., 2013). The gut microbiota imbalance can impose significant adverse effects on the host, including severe conditions such as cancer (Fan et al., 2021), inflammatory dysregulation in the bowel (Quaglio et al., 2022), obesity (Mitev and Taleski, 2019), rheumatoid arthritis (Zhao et al., 2022), cardiovascular disease (Xu et al., 2020), depression (Capuco et al., 2020), malnutrition (Khaledi et al., 2024), and increased vulnerability to infections (Gupta et al., 2022). Interest in the advantageous activities of the gut microbiota has led to the discovery of particular probiotic species with potential health-beneficial abilities. For example, probiotics present a feasible substitute for antibiotics in the human and veterinary sectors (Ali et al., 2023a). However, the beneficial effects of probiotics depend on individual strains (Bubnov et al., 2018). Some strains of the probiotic L. reuteri have been shown to provide several beneficial effects, such as enhancing growth performance, supporting gastrointestinal well-being, and the prevention and treatment of various diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, and liver damage, in both humans and animals (Yi et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2023). The potential benefits of L. reuteri are linked to the modulation of the immune response, preservation of gut microbiota equilibrium, and improvement of epithelial barrier integrity (He et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). It has been shown that L. reuteri I5007 can improve intestinal barrier function in neonatal pigs by promoting the expression of tight junction protein (Wang et al., 2022). In our previous investigation, we found that L. reuteri PSC102 strain obtained from the feces of a healthy weaned piglet possesses notable antioxidant activities (Ali et al., 2023b). Moreover, L. reuteri PSC102 can hinder the growth of enterotoxigenic E. coli in vitro (Ali et al., 2023b) and ameliorate immunosuppression by stimulating the development of immune organs, improving hematological functions, enhancing lymphocyte proliferation, and upregulating the levels of cytokines in cyclophosphamide-induced immune- suppressed mice (Ali et al., 2022) and rats (Ali et al., 2024). However, it is important to assess the presence of antibiotic-resistance genes and virulence factors using whole-genome sequencing prior to their use as probiotics. Moreover, it is essential to evaluate whole genomes to thoroughly unravel the structure and to understand specific genes with functional characteristics. Thus, this study aimed to determine the genomic diversity and potential of L. reuteri PSC102 as a probiotic through genome analysis and genomic characterization. Materials and MethodsBacterial culture, DNA extraction, and genome sequencingThe previous study isolated and identified L. reuteri PSC102 from a pig feces sample in Korea (Ali et al., 2023b). For genomic analysis, L. reuteri PSC102 cells were aerobically cultured in De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe medium (MB cell, SeoCho-Gu, Seoul, Korea) at 37°C for 24 hours. A QIAmp DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract and purify the genomic DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 1 ml of cultured L. reuteri PSC102 cells contained in an Eppendorf tube (etube) was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 7,500 rpm. After discarding the supernatant, 180 µl of animal tissue lysis-based cell lysis buffer (AL) solution was added to the pellet to obtain a final volume of 200 µl. Then, 20 µl of proteinase K was added, vortexed, and incubated at 56°C for 1–3 hours in a heat-block apparatus. The content was spin- down by vortexing, followed by the addition of 200 µl of AL and incubation for 10 minutes at 70ºC. A 200 µl of freshly prepared 96%–100% ethanol was mixed, transferred into a mini kit column tube, and centrifuged for 1 minute at 8,000 rpm. Afterward, 500 µl of wash buffer solution AW1 was added and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 1 minute. The content was then washed a couple of times with 500 µl of buffer solution AW2 by centrifugation for 3 minutes at 14,000 rpm. A 200 µl of elution buffer AE was added and incubated for 1 minute at 25ºC. Finally, after centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 1 minute, the filtrate containing the extracted DNA was collected in an etube. The obtained DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA) and a Gen5 microplate reader v3.08 (BioTek, Winooski, VT). At least 5–15 μg of genomic DNA were produced, and the OD260/280 ratio was between 1.8 and 2.0. The PacBio-Illumina (CJ Bioscience, Seoul, Korea) sequencing platform was used to sequence the genomic DNA of L. reuteri PSC102. Briefly, the purified genomic DNA was sheared into 8–10 kb fragments using the Covaris® g-TUBE® device, followed by the single- molecule real-time (SMRT) library preparation using the PacBio RS II system (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA), based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were purified by eliminating short reads less than 0.4 kb using 0.45 × AMPure PB beads. The sequencing primers were annealed to both ends of the SMRT DNA template with an average insert size of 500 bp and a DNA polymerase-to-template ratio of two. The polymerase binding kit P6 was used to load the libraries and enzyme-template complex by applying the MagBead loading method. The DNA sequencing reagent 2.0 kit was used to sequence SMRT cells, followed by sequence capture to optimize subread length using PacBio RS II. Gene assembly and annotationThe gene assembly was performed using the EzBioCloud program (Yoon et al., 2017). The starting of the chromosome was established based on the dnaA gene responsible for chromosomal replication and the guanine-cytosine (GC) skew pattern. The genome was annotated using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Process (PGAP) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/refseq/annotation_prok/process/). The genes were predicted using Glimmer 3 (www.cbcb.umd.edu/ software/glimmer) and functionally categorized using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, Clusters of Orthologous Group (COG), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases (Tatusov et al., 2000). Core and pan-genome comparisonsCore and pan genomes are typically used to assess genomic diversity within species or among closely related bacteria. The core genome of a species encompasses the total genes shared among all strains, including the genetic determinants that maintain the characteristics of the species. The pan-genome incorporates the whole gene pool, representing the capacity of genetic determinants. The core and pan-genomic analyses were conducted to examine the degree of functional conservation in the genome sequence according to the previously described method (Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013). For comparative analysis in this study, 10 complete genome sequences of the Limosilactobacillus species were selected: L. reuteri, Limosilactobacillus caviae, FTOY_s, Limosilactobacillus pontis, PNFV_s, Limosilactobacillus frumenti, Limosilactobacillus vaginalis, Limosilactobacillus panis, Limosilactobacillus antri, and Limosilactobacillus oris. The genome of L. reuteri and the genome sequence of L. reuteri PSC102 were used for the comparison. Phylogenetic analysis The phylogenetic tree was created using the maximum likelihood method based on the 16S gene sequencing analysis. The orthologous average nucleotide identity (OrthoANI) was calculated between the genomic sequences by converting OrthoANI values using the following formula: distance = (1 –(OrthoANI/100) (Lee et al., 2016). The genome of each sample strain was determined using OrthoANI with a threshold value of ≤99%. The neighbor-joining approach was used to calculate the evolutionary distance based on the genome-distance matrix. The phylogenetic tree was prepared using molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software (Tamura et al., 2013). The branch lengths are displayed in the same units corresponding to the evolutionary distances based on the scale. The nucleotide sequences were obtained from the NCBI PGAP database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ refseq/annotation_prok/process/), and extremely close average nucleotide identity (ANI) values (≤99%) were considered similar to those of L. reuteri PSC102. The 1,000 bootstrap repeats were used to evaluate the tree reliability. Moreover, taxonomic phylogenetics was used to check relationships within groups of meaningful genomes through unweighted pair group analysis with an arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram and Venn diagram. Antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factorsWe examined the presence of antibiotic resistance genes of different classes (lincosamides: clindamycin; aminoglycosides: kanamycin; macrolides: erythromycin and tylosin; tetracyclines: tetracycline; phenicols: chloramphenicol; penicillins: ampicillin; and glycopeptides: vancomycin) in L. reuteri PSC102. The presence of these genes was analyzed using NCBI’s National Database of Antibiotic-Resistant Organisms (NDARO, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/ antimicrobialresistance/). The criteria were the antimicrobial resistance gene identity threshold (90%) and minimum length (60%). Virulence factors from genomic data were analyzed using the Virulence Factor Database (https://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/main.htm). Sequences with a high probability of being virulence genes were searched using the BLASTN program with a specific parameter (evalue = 1.0E–7, percentage_ identity = 90.0). Ethical approvalNot needed for this study. ResultsGenome features of L. reuteri PSC102The complete genome of L. reuteri strain PSC102 consisted of a single circular chromosome (Fig. 1). The genomic similarities varied from 96.9% to 99.7% based on 16 rRNAs (Supplementary Tables S1), whereas the similarities according to ANI ranged from 87.2% to 99.8% (Supplementary Table S2). Among them, two L. reuteri strains (L. reuteri and L. reuteri PSC102) were positioned on the same node in the ANI tree, having the highest similarity (99.8%) (Supplementary Fig. S1) based on the ANI value. A total of 2,048,626 bp was acquired through PacBio-Illumina sequencing. A summary of the raw data sequencing results is presented in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4. The size of the whole genome was approximately 2 Mb, the GC content was 38.9%, and 2,040 protein-coding genes (CDSs) were present. The chromosome contains six 16S rRNAs, 18 rRNAs, and 69 tRNAs (Table 1). The whole-genome sequence (PRJNA1250387, PV459993) was deposited in the GenBank database. Functional classificationOut of the 1,846 CDSs, a significant proportion of 1,358 CDSs (73.56%) were precisely allocated to clusters representing COG families comprising 19 distinct functional categories (Table 2). Among them, a total of 488 genes had unknown functions. Additionally, the CDSs were mainly categorized into functional classes for i) replication, recombination, and repair (216 genes); ii) translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (140 genes); iii) amino acid transport and metabolism (138 genes); iv) carbohydrate transport and metabolism (113 genes); v) transcription (112 genes); vi) cell wall/ membrane/envelope biogenesis (88 genes); vii) coenzyme transport and metabolism (84 genes); viii) nucleotide transport and metabolism (83 genes); ix) energy production and conversion (75 genes); x) inorganic ion transport and metabolism (70 genes); xi) signal transduction mechanisms (50 genes); xii) posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones (49 genes); xiii) lipid transport and metabolism (43 genes); xiv) defense mechanisms (34 genes); xv) intercellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport (20 genes); xvi) cell cycle control, cell division, and chromosome partitioning (20 genes); and xvii) secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism (18 genes). The CDS and KEGG annotations of L. reuteri PSC102 genome were presented in Supplementary Table S5.

Fig. 1. Circular genome map of Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. The outermost circle represents the forward annotated reference gene, and the inner circle represents the reverse sequence, which indicates a beam. The inner red and gray regions show the rRNA and tRNA sequences in this genome. The inner circle represents a GC skew graph, which indicates the replication start points and leading/lagging strands. Mean GC of the genome after setting the skew value as a baseline: values higher than the average are displayed in green, and values lower than the average are displayed in red. The innermost circle shows the GC ratio graph used to observe the contours of the genome in regions where GC content is relatively uniform (isochore). GC ratio similarity: after setting the average value of the GC ratio of the genome as a baseline, values higher than the average are expressed in blue, and values lower than the average are expressed in yellow. Table S1. Supplementary Table S1. Analysis results using 16S rRNA gene.

Table S2. Supplementary Table S2. Analysis results using ANI.

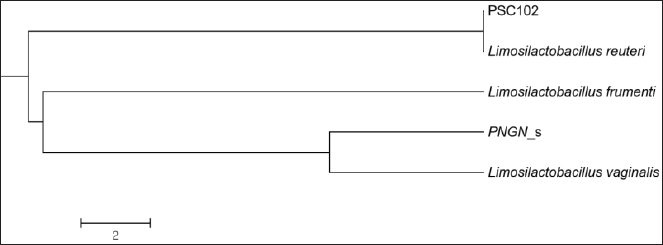

Fig. S1. Supplementary Fig. S1. UPGMA dendrogram using ANI values. Table S3. Supplementary Table S3. PacBio sequencing read stats.

Table S4. Supplementary Table S4. Illumina sequencing read stats.

Table 1. Genome summary of Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102.

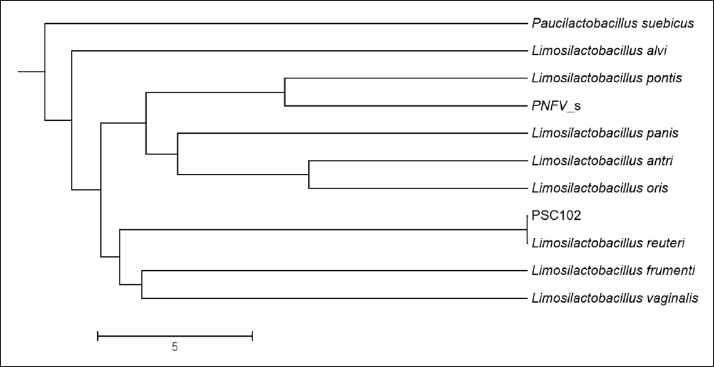

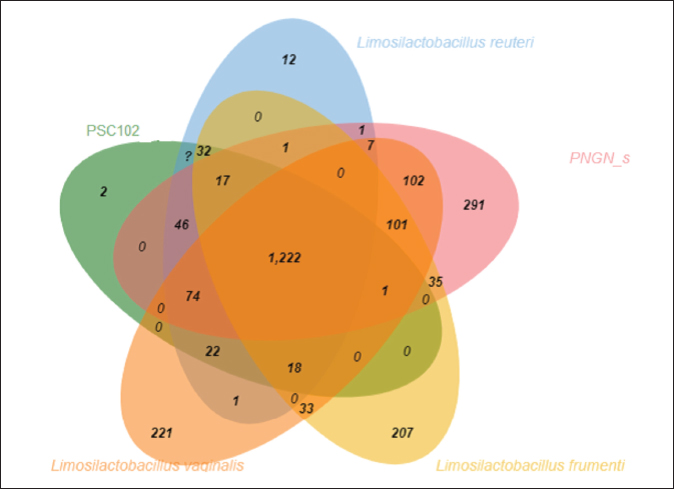

Phylogenetic comparison analysisIn the phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, L. reuteri PSC102 exhibited a significant degree of similarity with the L. reuteri group, a subgroup of the broader Limosilactobacillus genus. The L reuteri PSC102 exhibited a resemblance >99% to other strains of L reuteri. The presence of two strains of L. reuteri was observed in both the 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree and the OrthoANI tree, as depicted in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. It was challenging to differentiate between the L. reuteri genomes based solely on sequence similarity because the genomes had identical 16S rRNA sequences and extremely close OrthroANI values (e.g., ≤99%). On the 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree, L. reuteri, L. pontis, L. frumenti, L. vaginalis, L. antri, and L. oris were the species most similar to L. reuteri PSC102 (Fig. 2). On the ANI phylogenetic tree, however, L. reuteri was closest to L. reuteri PSC102 (Fig. 3). Core and pan-genome analysisA notable characteristic was identified in the genomes of the five Limosilactobacillus strains, namely L reuteri PSC102, L. reuteri, L. vaginalis, L. frumenti, and PNGN_s (Fig. 4). Moreover, the pan-genome analysis revealed that the genes of L. reuteri PSC102 contain 2,528 functional clusters. The genomes of the five Limosilactobacillus strains were analyzed by orthologous protein clustering to identify relationships with the L. reuteri PSC102 strain (Fig. 4). Of the entire set of 2,446 gene clusters, a total of 1,222 gene clusters were identified as core gene clusters. Only two gene clusters were strain-specific in L. reuteri PSC102. Among the genus Limosilactobacillus, a total of 74 gene clusters were identified as being unique. Of these clusters, 221 were found exclusively in L. vaginalis, whereas the remaining 512 clusters were observed in the other strains. Table 2. The proportion (%) of functional genes of Lactobacillus reuteri PSC102 assigned to clusters of orthologous group (COG) categories.

Fig. 2. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 was constructed using 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Analysis of antibiotic resistance and virulence genesThe results of the detection of resistance genes in L reuteri PSC102 for each type of antibiotic from genomic data are presented in Table 3. It was found that resistance genes were not present in our examined strain. Furthermore, the presence of different virulence genes was assessed in Limosilactobacillus PSC102. The results of detecting four types of toxic virulence genes from the genome data of L. reuteri PSC102 are presented in Table 4. No virulence genes, such as cylA, asa1, hyl, and gelE, representing cytolysin, aggregation substance, hyaluronidase, and gelatinase, were detected in L. reuteri PSC102.

Fig. 3. Analysis of the phylogenetic tree of Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 using ANI.

Fig. 4. Numbers of orthologous and unique genes among Limosilactobacillus strains. The Venn diagram shows the shared genetic relationships through the number of orthologous gene clusters of the core genome (the center part) and the number of unique genes of each genome. The colors denote the various strain sampling areas. DiscussionThe genome analysis using the 16S rRNA gene sequence and ANI showed that L. reuteri PSC102 was categorized under the genus Limosilactobacillus and was similar to the other members of the same group by >99%. The genome contains several specific genes with functional characteristics. Moreover, this strain does not contain any of the tested antimicrobial resistance genes or virulence factors. The genomic analysis revealed that L. reuteri PSC102 contains a single circular chromosome with a genome size of 2.05 Mb and a GC content of 38.9%. The possession of smaller genome size and lower GC content of L. reuteri PSC102 compared to L. plantarum (Zhang et al., 2018), L. brevis (Ellegaard and Engel, 2016), L. rhamnosus (Jarocki et al., 2018), L. gasseri (Marcotte et al., 2017), and L. fermentum (Illeghems et al., 2015) likely enables L. reuteri to adapt more effectively to the gut environment. Previous research has shown that L. reuteri with smaller genomes and lower GC content exhibit a higher rate of reductive evolution—adapting to survive and thrive in a restrictive environment (Papizadeh et al., 2017). Moreover, the genome with lower GC content can produce more mutations than the genome with higher GC content, suggesting a higher degree of variation in the L. reuteri PSC102 genome. The mutations in L. reuteri PSC102 may facilitate host adaptation, which may be useful for its application as a probiotic (Ortiz-Velez et al., 2018). The 16S rRNA genes can have similarities higher than the 97% common species identification criterion between different species, making species-level identification difficult. Therefore, for more accurate classification identification, we conducted an analysis using ANI values, which indicate the similarity between whole-genome sequences. The phylogenetic analysis using 16S rRNA gene sequencing showed that L. reuteri PSC102 was similar to the other members of the same genus by >99%. In addition to studies based on 16S rRNA sequences, phylogenetic analyses using ANI have accurately depicted the functional links between strains. The ANI value-based and 16S rRNA sequence- based phylogenetic trees had different evolutionary relationships. However, both the ANI tree and the 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree showed that the L. reuteri PSC102 strain is in a similar position to L. reuteri. It was revealed that bacterial properties can vary even within the same species (Zhang et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the phylogenetic analysis offers a dependable and detailed method for distinguishing closely associated species. Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 possesses distinctive genetic evolution patterns, which support its ability to adjust to the gastrointestinal environment effectively. Moreover, previous studies showed that the L reuteri PSC102 strain enhances growth performance, develops immune blood parameters, and improves immune response, supporting its beneficial activities (Ali et al., 2024). Table 3. Detection of antibiotic resistance genes in Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102.

Table 4. Detection of virulence factor genes in Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102.

The L. reuteri PSC102 genome possessed a total of 1,846 genes functionally annotated by COG. Among them, the COG class of unknown functions (488 genes) accounted for a significant proportion, suggesting that extensive research is needed to ascertain the potential roles of these genes. Among others, 113 genes (6.1%) were involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism, and 138 genes (7.4%) were linked to amino acid transport and metabolism. Limosilactobacillus can convert carbohydrates into SCFAs as an additional source of energy (Nowak et al., 2022). Moreover, SCFAs can modulate electrolyte absorption and cytokine production, thereby maintaining gut microbial balance (LeBlanc et al., 2017). In addition, amino acid transport and metabolism can play important roles in energy regulation and protein homeostasis, linking gut ecology and host health, as amino acids are among the major components in diets (Dai et al., 2011). A total of 34 genes were related to the defense mechanisms involved in the protection against the biological effects of O6-methylguanine in DNA. Moreover, alkylated guanine in DNA can be repaired by stoichiometrically transferring the alkyl group at the O-6 position to a cysteine residue in the enzyme. In total, 112 genes were assigned as transcription factors, comprising multiple transcriptional regulators and antirepressors, maintaining the control expression of specific genes during their presence in the gut. Furthermore, L. reuteri PSC102 contains many other essential genes, including genes involved in translation, biogenesis, replication, and nucleotide transport and metabolism. The results related to this study’s functional genes are consistent with previously published reports on Lactobacillus spp. (Zhang et al., 2019). In addition, gut-origin strains can develop surface-related and metabolic proteins to adapt to the harsh environment of the gut (O’sullivan et al., 2009). The L. reuteri PSC102 contains different genes that encode heat shock proteins Hsp20 and chaperons grpE, dnaK, dnaJ, and groEL. These genes actively participate in the response to hyperosmotic and heat shock by preventing the aggregation of stress-denatured proteins (Chen et al., 2019). The regulatory proteins are crucial for the adaptation of bacteria to different environmental conditions. The L. reuteri PSC102 genome contains various genes that encode for different regulatory proteins, including oxygen regulatory protein (NreC), phosphate regulatory protein (PhoB and PhoR), and transcriptional regulatory protein (YvrH and BaeR). The presence of these regulatory proteins may vary depending on the living conditions of the probiotics in the host to adapt to the various environmental niches, including living styles and diets (Zhang et al., 2024). Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 contains different genes associated with the transporter system, demonstrating the interaction between the strain and its environment. The ATP-dependent transporter SufC acts synergistically with SufE to stimulate SufS cysteine desulfurase activity. The SufBCD complex contributes to the assembly or repair of oxygen-labile iron-sulfur clusters under oxidative stress. The putative fluoride- ion transporter CrcB repair system catalyzes the recognition and processing of DNA lesions. A damage recognition complex composed of 2 UvrA and 2 UvrB subunits scans DNA for abnormalities for repair. The nitrate transporter NarT is required for nitrate uptake under anoxic conditions and is also involved in the excretion of nitrite produced by the dissimilatory reduction of nitrate. The energy-coupling factor transporter transmembrane protein EcfT provides the energy necessary to transport a number of different substrates. Moreover, the ABC transporter permease protein YqgI is responsible for the translocation of the substrate across the membrane. Extracellular proteins are crucial to organisms’ interactions with the adjacent environment, facilitating communication and adhesion. This renders them particularly significant in the context of Limosilactobacilli because they may participate in microbe-microbe and host-microbe interactions. The potential extracellular proteins of L. reuteri PSC102, including those associated with the cell surface, were released and detected in the surrounding environment. These include glycoproteins, phosphoproteins, and sialic acids, which interact with host microbiota. Glycoprotein assists the growth of probiotics in the gut and provides a barrier against pathogens (Lin et al., 2020). Core and pan-genome analyses assess genomic diversity within a species or across closely related bacterial strains (Zhang et al., 2019). The core gene set of a species is the collective number of genes shared by all strains within the species. Moreover, these genes are responsible for maintaining the essential characteristics and properties of the species. The pangenome is the collective set of genes encompassing the full range of genetic determinants within a given population or species. This represents the overall capacity for genetic variation and diversity. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the distinct characteristics of the L reuteri PSC102, a comparative analysis was conducted between L. reuteri PSC102 and 10 entire genomes within L. reuteri group. This prominent trait was detected in the genomes of the Limosilactobacillus strains, including L. reuteri PSC102, L. reuteri, L. vaginalis, L. frumenti, and PNGN_s. Moreover, the core and pan-genomic analysis detected significant gene clusters with unique characteristics consistent with the previously reported findings (Zhang et al., 2018). The L. reuteri PSC102 genome was analyzed to determine the potential presence of antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors. As a result of the analysis, the searched antimicrobial resistance genes were absent in the strain, providing evidence that L. reuteri PSC102 can be used as a probiotic candidate for functional foods/feeds (Pariza et al., 2015). Moreover, virulence factors pose a threat to consumers, which necessitates careful monitoring during the probiotic screening process (Wang et al., 2021). The analysis result showed that the virulence genes were not detected in the entire genome of L. reuteri PSC102, ensuring that this strain can be used as a potential probiotic strain. ConclusionIn this study, a full-length analysis of L. reuteri PSC102 strain obtained from the feces of healthy pigs confirmed its probiotic characteristics. In particular, for this strain to be used as a probiotic, we confirmed that there are no virulence factors and resistance genes for any of the tested antibiotics in each class. These results corroborate the use of L. reuteri PSC102 strain as a probiotic in both humans and animals. Moreover, because this strain does not contain resistance genes, it can be generally recognized as safe. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. FundingThis research was supported in part by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (RS-2023-00240204) and in part by a grant (Z-1543081-2020-22-02) from the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, in South Korea. Authors’ contributionSCP: Developed the concept, reviewed the manuscript, and acquired funds. MSA, SAJS, and SJK: Developed the concept, performed the experiment, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. GYL and HYC: The authors performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript. Data availabilityAll data obtained are included in this manuscript. ReferenceAli, M.S., Lee, E.-B., Hsu, W.H., Suk, K., Sayem, S.A.J., Ullah, H.M.A., Lee, S.-J. and Park, S.-C. 2023a. Probiotics and postbiotics as alternative to antibiotics: an emphasis on pigs. Pathogens 12, 874. Ali, M.S., Lee, E.-B., Lim, S.-K., Suk, K. and Park, S.-C. 2023b. Isolation and identification of Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 and evaluation of its potential probiotic, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. Antioxidants 12, 238. Ali, M.S., Lee, E.-B., Quah, Y., Birhanu, B.T., Suk, K., Lim, S.-K. and Park, S.-C. 2022. Heat-killed Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 ameliorates impaired immunity in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Front. Microbiol. 13, 820838; doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.820838. Ali, M.S., Lee, E.-B., Quah, Y., Sayem, S.A.J., Abbas, M.A., Suk, K., Lee, S.-J. and Park, S.-C. 2024. Modulating effects of heat-killed and live Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102 on the immune response and gut microbiota of cyclophosphamide- treated rats. Vet. Q. 44, 1–18. Asare, P.T., Zurfluh, K., Greppi, A., Lynch, D., Schwab, C., Stephan, R. and Lacroix, C., 2020. Reuterin demonstrates potent antimicrobial activity against a broad panel of human and poultry meat Campylobacter spp. isolates. Microorganisms 8(1), 78. Bubnov, R.V, Babenko, L.P., Lazarenko, L.M., Mokrozub, V. V. and Spivak, M.Y. 2018. Specific properties of probiotic strains: relevance and benefits for the host. EPMA J. 9, 205–223. Capuco, A., Urits, I., Hasoon, J., Chun, R., Gerald, B., Wang, J.K., Kassem, H., Ngo, A.L., Abd-Elsayed, A. and Simopoulos, T. 2020. Current perspectives on gut microbiome dysbiosis and depression. Adv. Ther. 37, 1328–1346. Chen, L., Gu, Q., Li, P., Chen, S. and Li, Y. 2019. Genomic analysis of Lactobacillus reuteri WHH1689 reveals its probiotic properties and stress resistance. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 844–857; doi:10.1002/fsn3.934. Contreras-Moreira, B. and Vinuesa, P. 2013. Get_ homologues, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7696–7701. Dai, Z.-L., Wu, G. and Zhu, W.-Y. 2011. Amino acid metabolism in intestinal bacteria: links between gut ecology and host health. Front. Biosci. 16, 1768–1786. Ellegaard, K.M. and Engel, P. 2016. Beyond 16S rRNA community profiling: intra-species diversity in the gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1475–1483. Fan, X., Jin, Y., Chen, G., Ma, X. and Zhang, L. 2021. Gut microbiota dysbiosis drives the development of colorectal cancer. Digestion 102, 508–515. Gupta, A., Singh, V. and Mani, I. 2022. Dysbiosis of human microbiome and infectious diseases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 192, 33–51. He, J., Wang, W., Wu, Z., Pan, D., Guo, Y., Cai, Z. and Lian, L. 2019. Effect of Lactobacillus reuteri on intestinal microbiota and immune parameters: involvement of sex differences. J. Funct. Foods 53, 36–43. Illeghems, K., De Vuyst, L. and Weckx, S. 2015. Comparative genome analysis of the candidate functional starter culture strains Lactobacillus fermentum 222 and Lactobacillus plantarum 80 for controlled cocoa bean fermentation processes. BMC Genomics 16, 1–13. Jarocki, P., Podleśny, M., Krawczyk, M., Glibowska, A., Pawelec, J., Komoń-Janczara, E., Kholiavskyi, O., Dworniczak, M. and Targoński, Z. 2018. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus rhamnosus Pen, a probiotic component of a medicine used in prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children. Gut Pathog. 10, 1–6. Kamada, N., Chen, G.Y., Inohara, N. and Núñez, G. 2013. Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 14, 685–690. Khaledi, M., Poureslamfar, B., Alsaab, H.O., Tafaghodi, S., Hjazi, A., Singh, R., Alawadi, A.H., Alsaalamy, A., Qasim, Q.A. and Sameni, F. 2024. The role of gut microbiota in human metabolism and inflammatory diseases: a focus on elderly individuals. Ann. Microbiol. 74, 1. Lamas, A., Regal, P., Vázquez, B., Cepeda, A. and Franco, C.M. 2019. Short chain fatty acids commonly produced by gut microbiota influence Salmonella enterica motility, biofilm formation, and gene expression. Antibiotics 8, 265. LeBlanc, J.G., Chain, F., Martín, R., Bermúdez- Humarán, L.G., Courau, S. and Langella, P. 2017. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria. Microb. Cell Fact. 16, 1–10. Lee, I., Ouk Kim, Y., Park, S.-C. and Chun, J. 2016. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 1100–1103. Lin, B., Qing, X., Liao, J. and Zhuo, K. 2020. Role of protein glycosylation in host-pathogen interaction. Cells 9(4), 1022; doi:10.3390/cells9041022. Liu, Q., Yu, Z., Tian, F., Zhao, J., Zhang, H., Zhai, Q. and Chen, W. 2020. Surface components and metabolites of probiotics for regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier. Microb. Cell Fact. 19, 1–11. Marcotte, H., Andersen, K.K., Lin, Y., Zuo, F., Zeng, Z., Larsson, P.G., Brandsborg, E., Brønstad, G. and Hammarström, L. 2017. Characterization and complete genome sequences of L. rhamnosus DSM 14870 and L. gasseri DSM 14869 contained in the EcoVag® probiotic vaginal capsules. Microbiol. Res. 205, 88–98. Martens, E.C., Neumann, M. and Desai, M.S. 2018. Interactions of commensal and pathogenic microorganisms with the intestinal mucosal barrier. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 457–470. Mitev, K. and Taleski, V. 2019. Association between the gut microbiota and obesity. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 7, 2050–2056; doi:10.3889/ oamjms.2019.586. Nowak, A., Zakłos-Szyda, M., Rosicka-Kaczmarek, J. and Motyl, I. 2022. Anticancer potential of post- fermentation media and cell extracts of probiotic strains: an in vitro study. Cancers (Basel) 14(7), 1853; doi:10.3390/cancers14071853. O’sullivan, O., O’Callaghan, J., Sangrador-Vegas, A., McAuliffe, O., Slattery, L., Kaleta, P., Callanan, M., Fitzgerald, G.F., Ross, R.P. and Beresford, T. 2009. Comparative genomics of lactic acid bacteria reveals a niche-specific gene set. BMC Microbiol. 9, 1–9. Ortiz-Velez, L., Ortiz-Villalobos, J., Schulman, A., Oh, J.-H., van Pijkeren, J.-P. and Britton, R.A. 2018. Genome alterations associated with improved transformation efficiency in Lactobacillus reuteri. Microb. Cell Fact. 17, 138; doi:10.1186/s12934-018-0986-8. Papizadeh, M., Rohani, M., Nahrevanian, H., Javadi, A. and Pourshafie, M.R. 2017. Probiotic characters of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are a result of the ongoing gene acquisition and genome minimization evolutionary trends. Microb. Pathog. 111, 118–131. Pariza, M.W., Gillies, K.O., Kraak-Ripple, S.F., Leyer, G. and Smith, A.B. 2015. Determining the safety of microbial cultures for consumption by humans and animals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 73, 164–171. Quaglio, A.E.V., Grillo, T.G., De Oliveira, E.C.S., Di Stasi, L.C. and Sassaki, L.Y. 2022. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 4053–4060. Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. and Kumar, S. 2013. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. Tatusov, R.L., Galperin, M.Y., Natale, D.A. and Koonin, E.V. 2000. The COG database: a tool for genome- scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 33–36. Wang, Q., Wang, J., Qi, R., Qiu, X., Sun, Q., Huang, J. and Wang, R. 2022. Effect of oral administration of Limosilactobacillus reuteri on intestinal barrier function and mucosal immunity of suckling piglets. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 21, 612–623. Wang, Y., Liang, Q., Lu, B., Shen, H., Liu, S., Shi, Y., Leptihn, S., Li, H., Wei, J. and Liu, C. 2021. Whole-genome analysis of probiotic product isolates reveals the presence of genes related to antimicrobial resistance, virulence factors, and toxic metabolites, posing potential health risks. BMC Genomics 22, 1–12. Wu, H., Xie, S., Miao, J., Li, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, M. and Yu, Q. 2020. Lactobacillus reuteri maintains intestinal epithelial regeneration and repairs damaged intestinal mucosa. Gut Microbes 11, 997–1014. Xu, H., Wang, X., Feng, W., Liu, Q., Zhou, S., Liu, Q. and Cai, L. 2020. The gut microbiota and its interactions with cardiovascular disease. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 637–656. Yakout, H.M. and Eckhardt, E. 2022. Gastrointestinal tract barrier efficiency: function and threats, in: gut microbiota, immunity, and health in production animals. Berlin, Germany: Springer, pp: 13–32. Yi, H., Wang, L., Xiong, Y., Wen, X., Wang, Z., Yang, X., Gao, K. and Jiang, Z. 2018. Effects of Lactobacillus reuteri LR1 on the growth performance, intestinal morphology, and intestinal barrier function in weaned pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 96, 2342–2351. Yoon, S.-H., Ha, S.-M., Kwon, S., Lim, J., Kim, Y., Seo, H. and Chun, J. 2017. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 1613–1617. Yu, Z., Chen, J., Liu, Y., Meng, Q., Liu, H., Yao, Q., Song, W., Ren, X. and Chen, X. 2023. The role of potential probiotic strains Lactobacillus reuteri in various intestinal diseases: new roles for an old player. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1095555. Zhang, L., Kulyar, M.F., Niu, T., Yang, S. and Chen, W. 2024. Comparative genomics of Limosilactobacillus reuteri YLR001 reveals genetic diversity and probiotic properties. Microorganisms 12, 1636. Zhang, W., Ji, H., Zhang, D., Liu, H., Wang, S., Wang, J. and Wang, Y. 2018. Complete genome sequencing of Lactobacillus plantarum ZLP001, a potential probiotic that enhances intestinal epithelial barrier function and defense against pathogens in pigs. Front. Physiol. 9, 1689. Zhang, W., Wang, J., Zhang, D., Liu, H., Wang, S., Wang, Y. and Ji, H. 2019. Complete genome sequencing and comparative genome characterization of Lactobacillus johnsonii ZLJ010, a potential probiotic with health-promoting properties. Front. Genet. 10, 812. Zhao, T., Wei, Y., Zhu, Y., Xie, Z., Hai, Q., Li, Z. and Qin, D. 2022. Gut microbiota and rheumatoid arthritis: from pathogenesis to novel therapeutic opportunities. Front. Immunol. 13, 1007165. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALThe supplementary material can be accessed at the journal’s website | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Lee G, Cho H, Sayem SAJ, Ali S, Kim S, Park S. Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 Web Style Lee G, Cho H, Sayem SAJ, Ali S, Kim S, Park S. Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=237715 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Lee G, Cho H, Sayem SAJ, Ali S, Kim S, Park S. Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Lee G, Cho H, Sayem SAJ, Ali S, Kim S, Park S. Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 Harvard Style Lee, G., Cho, . H., Sayem, . S. A. J., Ali, . S., Kim, . S. & Park, . S. (2025) Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 Turabian Style Lee, Ga-yeong, Hae-yeon Cho, Syed Al Jawad Sayem, Sekendar Ali, Seung-joon Kim, and Seung-chun Park. 2025. Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 Chicago Style Lee, Ga-yeong, Hae-yeon Cho, Syed Al Jawad Sayem, Sekendar Ali, Seung-joon Kim, and Seung-chun Park. "Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Lee, Ga-yeong, Hae-yeon Cho, Syed Al Jawad Sayem, Sekendar Ali, Seung-joon Kim, and Seung-chun Park. "Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2427-2438. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Lee, G., Cho, . H., Sayem, . S. A. J., Ali, . S., Kim, . S. & Park, . S. (2025) Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri PSC102. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2427-2438. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.15 |