| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2478-2491 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2478-2491 Research Article Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australisSarah A. Abdulla1,2*, Farag A. Elshaari2, Mohamed Alshintari3 and Lazhar Zourgui41Faculty of Science of Bizerte, University of Carthage, Jarzouna, Tunisia 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya 3Libya Center for Biotechnology Research, Tripoli, Libya 4Research Laboratory BMA “Biodiversity, Molecules, Application” Higher Institute of Applied Biology of Medenine, University of Gabes, Medenine, Tunisia * Corresponding Author: Sarah A. Abdulla. Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya. Email: sara.abdulla [at] uob.edu.ly Submitted: 21/01/2025 Revised: 05/05/2025 Accepted: 16/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

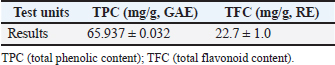

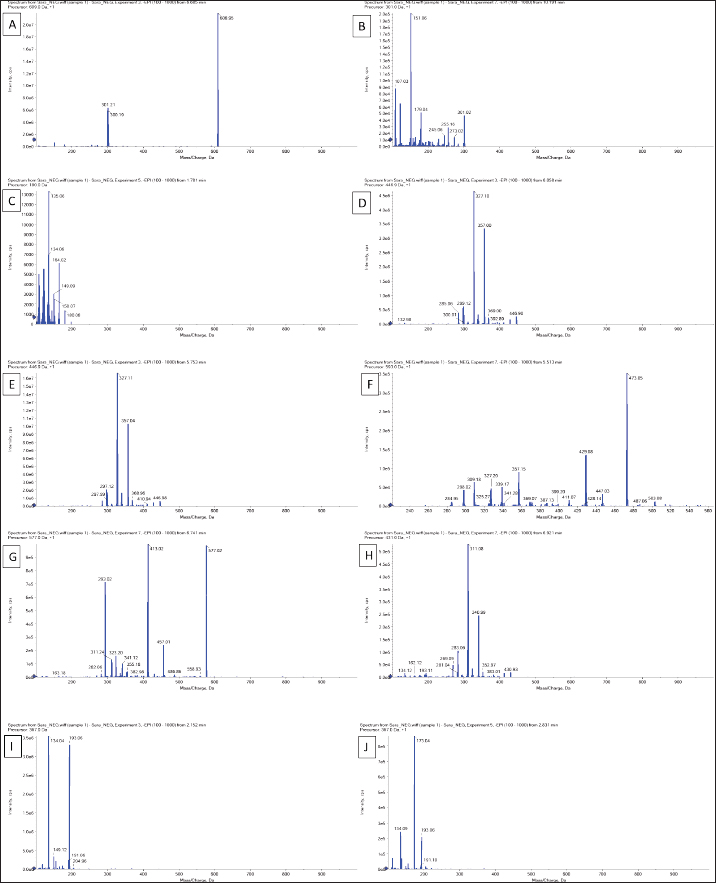

AbstractBackground: Phragmites australis, a grass species of the Poaceae family, was studied here for the first time in Libya, marking its initial documented phytochemical and biological evaluation. In traditional folk medicine, P. australis has a promising therapeutic potential. Aim: This study analyzed and identified phytochemical compounds and the antioxidant, cytotoxic, antimicrobial, and antiviral activities of Phragmites australis ethanolic extract (PAEE). Methods: Phytochemical profiling was conducted using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Antioxidant properties were evaluated using ferric reducing antioxidant power, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, nitric oxide, total antioxidant capacity, and Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity assays. The cytotoxic effects of the extracts on the breast (MCF-7), hepatocellular (Hep-G2), and colon (Caco-2) cancer cell lines were assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Antimicrobial effects were tested against four bacterial strains and three fungi, and the antiviral activities of the extracts against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and hepatitis A virus (HAV) were assessed. Results: The PAEE contained 65.94 mg/gallic acid equivalents g of total phenolics and 22.7 mg/RE g of total flavonoids. Phytochemical analysis revealed the presence of key bioactive compounds, including flavonoids such as rutin, quercetin, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, caffeic acid, and apigenin-6-C-glucoside, as well as phenolic acids, such as protocatechuic acid, coumaric acid, and feruloyl-quinic acid derivatives. The extract exhibited significant antioxidant activity. Additionally, the extract exhibited potent antimicrobial efficacy, particularly in counteracting Bacillus subtilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Conclusion: This study is the first to investigate P. australis from Benghazi, Libya, revealing its rich diversity of polyphenols and flavonoids, along with its strong antioxidant, antibacterial, and antiviral activities. Notably, this is the first report evaluating Libyan-sourced PAEE for its antiviral activity against HSV-1 and HAV, alongside its cytotoxic effects on colorectal adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cells. Keywords: Phragmites australis, LC–MS analysis, Phenolics, Antioxidant activity, Antiviral activity. IntroductionMedicinal plants are major reservoirs of bioactive substances that may be valuable therapeutic components vital for the management of diseases and enhancement of health and are used as precursors for drug production and biosynthesis. Modern synthetic drugs are associated with undesirable side effects that may lead to other pathological complications (Salam and Quave, 2019) Phytochemicals are secondary plant metabolites. They are naturally found in plants, and they exhibit considerable biological activity. They provide health benefits that exceed the effects of essential nutrients. Phytochemical biological activities include antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-atherogenic, anticancer, and antidiabetic effects. Furthermore, they promote the regulation of hormone metabolism and support immune system development. Phytochemicals are also present in nonessential nutrients, such as coffee beans, and exhibit significant properties that contribute to the management of various common diseases (Acidri et al., 2020). Phytochemical screening is a vital process in drug discovery, and plant-derived pharmaceutical drugs are typically unique compounds that are isolated through industrial separation and extraction of components with therapeutic properties (Falzon and Balabanova, 2017). Phragmites australis, a perennial grass species within the Poaceae family, exhibits exceptional adaptability to abiotic stressors because of its diverse intraspecific variation and high level of phenotypic plasticity. As a result, this species has considerable ecological importance and displays remarkable resilience under diverse environmental conditions (Cui et al., 2023). Phragmites australis is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine (Fang et al., 2024). This study investigates the phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Phragmites australis ethanolic extracts (PAEE), while focusing on the ecological Libyan pattern that can contain bioactive compounds as a result of their adaptation to dry Mediterranean environments. While previous research has mainly focused on aqueous extracts (Unuofin et al., 2024a,b), our study relied on ethanol extraction to recover a broader spectrum of metabolites— including flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolic acids— through comprehensive liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) profiling. Our work tackles critical gaps by: (1) providing the first phytochemical characterization of Libyan-sourced ethanolic extracts, (2) revealing novel antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and hepatitis A virus (HAV), and (3) demonstrating distinct cytotoxicity against colorectal adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cells compared with existing breast/lung cancer models. These findings expand the phytochemical and pharmacological properties of P. australis and highlight its solvent-specific therapeutic potential. Materials and MethodsChemicals and reagentsThe ethanol used for the extraction process was sourced fromAlkomed(Kimya Kozmetic San, Turkey). Mueller–Hinton Agar (MHA) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Co. Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, sodium nitrate (NaNO3), 5% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, 7% aluminum chloride (AlCl3) solution, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), trichloroacetic acid, ethanol, gallic acid, and ascorbic acid were acquired from Bio-Rad, France. Plant materialPhragmites australis aerial parts were collected from Wadi Qattara, Benghazi, Libya, at the end of March 2023 and were identified and classified by the Biotechnology Research Center, Tripoli, Libya. The collected plant materials were dried at room temperature, ground into smaller particles using a milling cutter, and subsequently preserved in airtight plastic containers for subsequent analytical procedures. To prepare the extracts, 250 g of dried plant material was extracted with 95% ethanol, and three consecutive extractions were performed for 24 hours. The solution was passed through filter paper, and the resulting filtrate was evaporated using a rotary evaporator maintained at 45°C. Evaluation of the phytochemical composition of P. australis extractTotal phenolic content (TPC)The TPC of PAEE was determined via the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent spectrophotometric method, which relies on the formation of a colored complex proportional to the phenolic content in the sample. One milliliter of the extract was dissolved in two milliliters of methanol. From this solution, 500 ml were combined with 2.5 ml of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. After allowing the mixture to stand for 5 minutes, 2.5 ml of a sodium carbonate solution (containing 75 g/l Na2CO3) was added. The mixture was then incubated in the dark at room temperature for approximately 2 hours. The absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a spectrophotometer. The results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry matter on the basis of a calibration curve constructed using gallic acid standards (Siddiqui et al., 2017; Molole et al., 2022). Total flavonoid content (TFC)The TFC of PAEE was quantified via the aluminum chloride colorimetric method following an optimized protocol for precision and reproducibility. One milliliter of the ethanolic extract was diluted in two milliliters of methanol to create a stock solution. Two hundred microliters of this mixture were pipetted into a 10-ml volumetric flask, and 75 µl of 5% sodium nitrate solution was added. The mixture was left to stand at room temperature for 5 minutes. Next, 1.25 ml of 7% aluminum chloride solution was added, and the reaction proceeded for an additional 5 minutes. Next, 0.05 ml of 5% sodium hydroxide solution was added, and the mixture was thoroughly mixed, allowing the reaction to continue for another 5 minutes at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm using a UV spectrophotometer, with methanol used as the blank control. A calibration curve was generated using quercetin standards at concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 µg/ml. The flavonoid content was calculated as milligrams of quercetin equivalent per gram of dry extract (mg QE/g) on the basis of the standard curve. The results are reported as mean values derived from triplicate measurements (Shraim et al., 2021). A calibration curve was developed using quercetin as a standard. LC–MS analysisThe compounds were analyzed using an Exion LC AC liquidchromatographysystem. Inthenegativeionization mode, a gradient mobile phase was introduced into the samples. The flow rate was maintained at 0.3 ml/min, and injections of 5 µl were performed. MS1 data were collected within a scan range of 100–1,000 Da, with a curtain gas pressure of 25 psi, source temperature of 500°C, Ion Spray voltage of –4500 V, and collision energy of –3535 V. In the positive ionization mode, the same column and gradient protocol were used with ammonium formate at pH 3. The MS1 acquisition settings included a curtain gas pressure of 25 psi, an IonSpray voltage of 5500 V, a source temperature of 500°C, and a collision energy of 35 V. A calibration standard comprising 24 organic acids was prepared in 5 mM ammonium formate at approximately 100 µg/ml (200 µg/ml for levulinic acid) and serially diluted for calibration purposes. The hydrolysate samples were filtered, diluted, and analyzed both with and without the addition of standards to evaluate the analyte recovery and matrix effects. Recovery was determined by comparing the results of spiked and unspiked hydrolysates. Repeatability was evaluated by performing analyses on multiple days. Analytes below the quantification limit, such as transaconitic acid, glutaric acid, fumaric acid, 2-hydroxy-2-methylbutyric acid, and adipic acid, were spiked at approximately 10 ppm for accurate measurement. Analysis of the antioxidant capacity of PAEEDPPH radical scavenging assayThe DPPH radical scavenging assay was performed following established methods (Boly et al., 2016), with adjustments to adapt it to a 96-well plate. A 100 µl ethanolic DPPH solution (0.025 g/l, equivalent to 2.5 mg/100 ml ethanol) was prepared, and 1 ml of this solution was combined with 3 ml of each ethanol extract at concentrations ranging from 3.9 to 1,000 µg/ml. A control was prepared by mixing 100 µl of ethanol with 1.9 ml of an ethanolic DPPH solution. An ascorbic acid solution was used as the positive control. The mixtures were incubated for 30 minutes, after which the absorbance was recorded at 517 nm. The percentage inhibition (PI %) was calculated using the following formula: PI% = [(Blank absorbance –Average absorbance of the test)/Blank absorbance] *100 The median inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined by plotting the percent inhibition (I%) against the logarithm (Log) of the sample concentration. Reducing power assayThe ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay was conducted in microplates according to the method outlined by Benzie and Strain (1996) with some adaptations (Benzie and Strain, 1996; Athamena et al., 2019). Ascorbic acid at a concentration of 1 mg/ ml) was used as the positive control in the experiment. Antioxidant agents reduce ferric ions (Fe3+) to ferrous ions (Fe2+). The steps were taken as reported by Wakeel et al. (2019). Antioxidant capacity determined by phosphomolybdenum assayThe total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the extracts was evaluated using the phosphor molybdenum method, following the procedure outlined by Prieto et al. (1999) with minor adjustments made by Zourgui et al. (2020). Nitric oxide (NO) scavenging activity assayThe NO scavenging activity was assessed using the methodology outlined by Jagetia and Baliga (2004). ABTS radical scavenging activity assayThe antioxidant potential of the extract against ABTS radicals was evaluated using the Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay, as outlined by Chang et al. (2008) and Zourgui et al. (2020). Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of the ethanol extract by MTT assayThe cytotoxic effects of the ethanol extract were evaluated using the MTT assay, following the protocol established by Van de Loosdrecht et al. (1994), Abdelaziz et al. (2024). Extract solutions were centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 10 minutes) to remove insoluble precipitates before application to cell cultures. This study utilized the following cell lines to determine the cytotoxic or anticancer properties of the extract: breast cancer cell line (MCF-7), hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (Hep-G2), human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line (Caco-2), and normal human diploid cell line (WI-38). All cell lines were obtained from the Laboratory of Biologically Compatible Substances, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Monastir, Tunisia. For the assay, cells were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml, with 100 µl added to each well, and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours to allow the formation of a complete monolayer. Following incubation, the growth medium was removed, and the monolayer was washed twice with wash media. Twofold dilutions of the test samples were prepared in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium supplemented with 2% serum (maintenance medium). A volume of 0.1 ml of each dilution was added to the wells, with the three wells serving as the controls and receiving only the maintenance medium. The plates were incubated at 37°C and were monitored for signs of toxicity, such as partial or complete monolayer detachment, cell rounding, shrinkage, or granulation. Subsequently, 20 µl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in PBS, Bio-Rad, France) was added to each well. The plates were shaken (150 rpm) for 5 minutes to ensure proper mixing of the MTT with the media. The mixture was then maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 4 hours to facilitate MTT metabolism. After incubation, the media were discarded, and the plates were dried on paper towels to remove residual liquid. The formazan crystals, which are the metabolic product of MTT, were dissolved in 200 µl of DMSO, and the plates were shaken again at 150 rpm for 5 minutes to ensure thorough mixing. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm with background correction at 620 nm. Antimicrobial screeningPreparation of microbial suspensionsTest bacteria, including Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, were cultured on MHA plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The optical density (OD) at 625 nm was adjusted to 0.08–0.10, equivalent to approximately 106 CFU/ml For fungal strains, including Candida albicans ATCC 10221, and Mucor circinelloides AUMMC 11656, cultures were grown on Sabouraud agar at 30°C until full mycelial development was achieved. The spore suspensions were prepared by adding 10 ml of sterile water containing Tween 80 to the plates, with the OD adjusted to 0.08–0.10 to achieve approximately 106 spores/ml. Measurement of antimicrobial properties via the agar well diffusion (AWD) techniqueAntimicrobial activity was evaluated using the AWD method on MHA plates in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (Espinel-Ingroff et al., 2007). The Petri dishes were filled with 20 ml of MHA (pH 7.2–7.4) and allowed to solidify. Once the microbial cultures reached the desired growth phase, a sterile cotton swab was used to evenly spread the microbial suspension across the agar surface, creating a uniform lawn. Wells 6–8 mm in diameter were aseptically prepared using a sterile cork borer or pipette tip. Each well was filled with 20–100 µl of the ethanolic extract of P. australis at the specified concentration. The controls included DMSO as a negative control, gentamicin as a positive control for bacterial strains, and fluconazole as a positive control for fungal strains. The bacterial plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, while the fungal plates were incubated at 30°C for 4–7 days. After incubation, the zones of inhibition were measured in millimeters, with diameters less than 5 mm considered ineffective (Espinel-Ingroff et al., 2011; Tiama et al., 2023). Antiviral assaysDetermination of the maximum nontoxic concentration (MNTC)The African green monkey kidney cell line VERO-E6 was used. The cells were maintained under a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. The cytotoxicity of PAEE was assessed on the basis of cellular morphological changes following the method described by El Gendy et al. (2022). The MNTC was determined by plotting the toxicity percentage against the sample concentration. DMSO was used as a control and exhibited no activity (El Gendy et al., 2022). Determination of the percentage antiviral effectThe HSV1 and HAV viruses were obtained from the Microbiology Department, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University. A 96-well antiviral assay using VERO-E6 cells was developed on the basis of protocols previously established by El Gendy et al. (2022) and van de Sand et al.(2021). Statistical analysisIn the experimental design, all tests were performed in triplicate. The findings were analyzed using mean values and standard deviations to ensure precision and reliability and presented as mean ± standard error of mean. Statistical evaluation was conducted using IBM SPSS version 22. The data were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to compare the mean values. A multiple comparison test was used to determine significant differences among groups. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ResultsPhytochemical composition of P. australisTo investigate the presence of secondary metabolites, the TPC and TFC in PAEE were quantified using specific standard curves. The results, as shown in Table 1, are expressed as milligrams per gram of GAE (mg/g GAE) for total phenolics and rutin equivalent (mg/g RE) for flavonoids. LC–MS analysis of the PAEEThe notable levels of total polyphenols and flavonoids in PAEE were confirmed through LC–MS analysis. Ten compounds were identified by comparing their mass spectral data and fragmentation patterns with those reported in the literature (Table 2, Fig. 1). The notable compounds included rutin, quercetin, caffeic acid, luteolin (LUT)-6-C-glucoside, and LUT-7-O-glucoside, along with flavonoid glycosides. For example, rutin was identified by its molecular ion peak at m/z 609 (Rt = 6.685 min), and caffeic acid was identified by its peak at m/z 180, which is consistent with known fragmentation patterns (Pedro et al., 2023; Abd-El-Aziz et al., 2024). The primary phenolic compounds 3-O-feruloyl-quinic acid and 4-O-feruloyl-quinic acid were characterized by their molecular ion peaks at m/z 367. Flavonoids, such as apigenin 6-C-glucoside and LUT derivatives, were also detected, confirming the rich phenolic and flavonoid composition of PAEE. Antioxidant activity of P. australisThe antioxidant activity of PAEE was assessed using the FRAP, DPPH, NO, TAC, and TEAC methods. The notable antioxidant activity of PAEE (Table 3) was consistent with its phytochemical profile and the findings from LC–MS analysis. The antiradical activity of the extract was assessed via DPPH, with the results expressed in IC50 and compared with that of ascorbic acid. The IC50 value for the extract was 12.62 µg/ml, indicating strong antioxidant activity, although weaker than that of ascorbic acid (IC50 = 2.85 µg/ml) (Table 3). The FRAP assay was used to assess the reducing power of the extract, with ascorbic acid used as the reference standard. As shown in Table 1, the reducing capacity of the extract, expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE), was 476.95 ± 0.21 µg/mg, demonstrating a significant ability to reduce ferric ions. The TAC of the extract was 93.5 ± 1.7 mg AAE/g, indicating high antioxidant potential. The ABTS radical-scavenging activity of the extract was 0.78 ± 0.23 mmol Trolox/g, reflecting its ability to effectively inhibit the absorption of ABTS+• radicals. These findings confirm the high antioxidant potential of P. australis ethanol extract. Table 1. Phenolic and flavonoid contents of the PAEE.

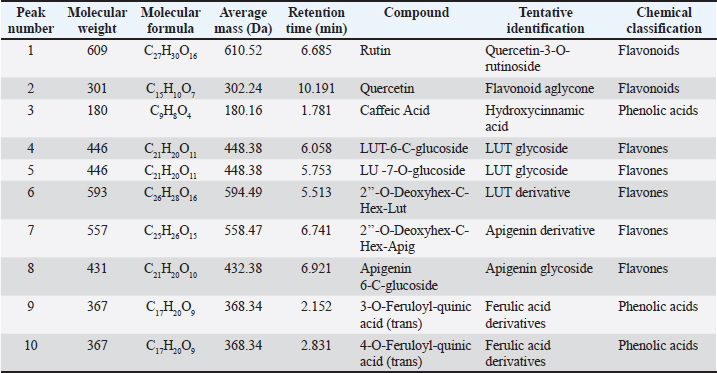

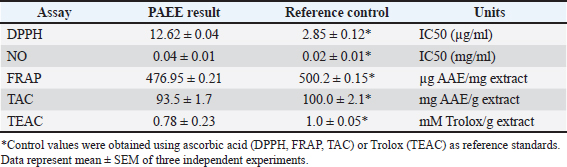

Table 2. Compound contents of the PAEE identified via LC–MS/MS.

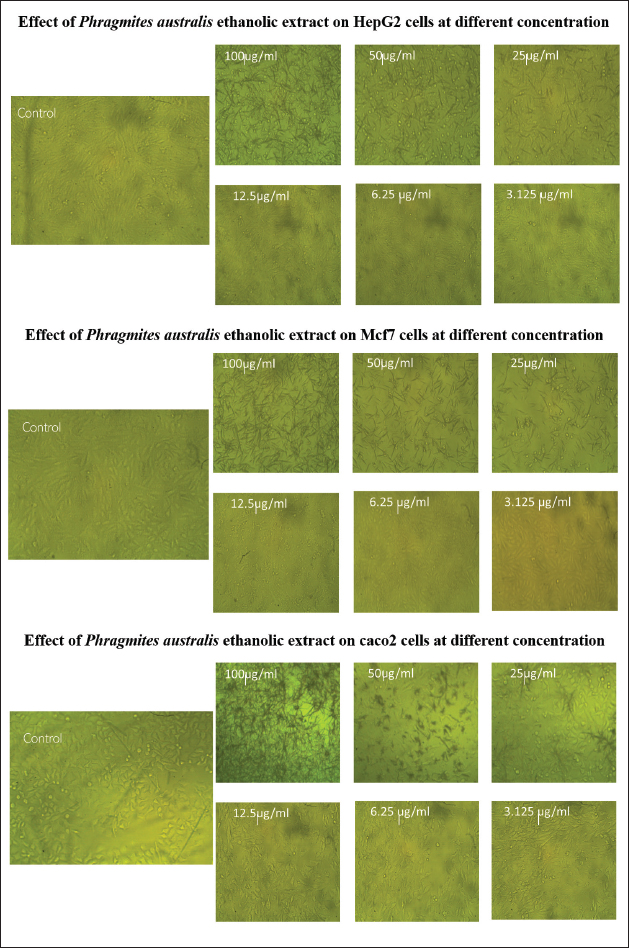

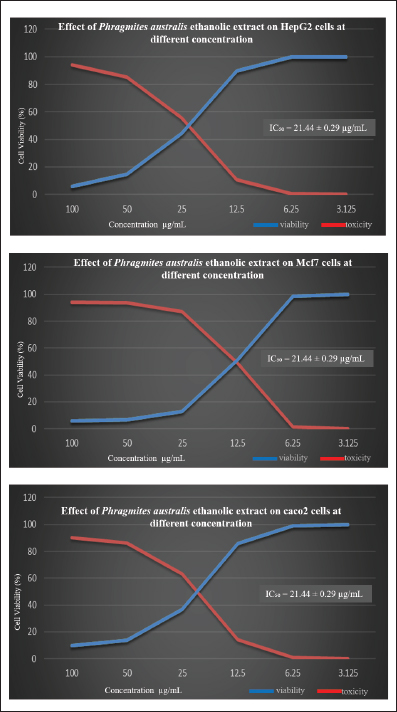

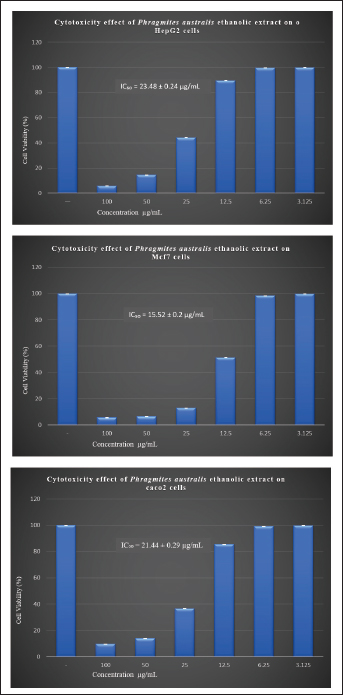

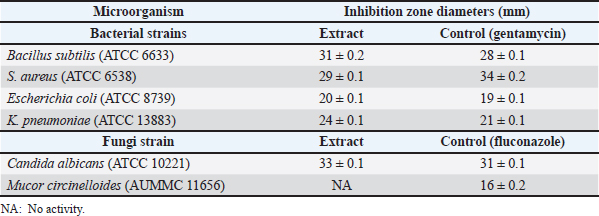

Cytotoxic activity of P. australis extractThe cytotoxic activity of PAEE was assessed in HepG2, Caco-2, and MCF-7 cancer cell lines. Cancer cell lines serve as critical models in biomedical research, facilitating the study of carcinogenesis and the development of anticancer therapies (Chen et al., 2013). These models are instrumental in evaluating the efficacy of natural and synthetic compounds in inhibiting metastasis and proliferation, promoting autophagy, enhancing chemosensitivity, and inducing programmed cancer cell death (Yan et al., 2020). As depicted in Figures 2–4, untreated control cells exhibited a regular monolayer structure and formed clusters. However, treatment with varying concentrations of PAEE-induced significant morphological alterations, particularly affecting the cell surface and cytoskeleton. The extract demonstrated an IC50 value of 23.48 ± 0.24 µg/ml against HepG2 cells, with no significant variation in cytotoxicity compared with that of the control (p ≤ 0.6). In MCF-7 cells, untreated controls displayed a polygonal morphology with distinct boundaries, whereas treatment with PAEE caused notable morphological changes, yielding an IC50 of 9.61 ± 0.13 µg/ml. The cytotoxic effect was significantly different from that of the control (p ≤ 0.05). Similarly, in Caco-2 cells, control cells maintained a regular cylindrical shape, but treatment with the extract resulted in substantial cellular damage, with an IC50 of 21.44 ± 0.29 µg/ml. The cytotoxic effect was also significantly different from that of the control (p ≤ 0.05). These results underscore the potent cytotoxic effects of PAEE, particularly against the MCF-7 and Caco-2 cell lines, indicating its potential as a promising candidate for anticancer therapy. Antimicrobial activity of P. australisThe antimicrobial properties of P. australis extract were evaluated in four bacterial strains and two fungal species. The antimicrobial activity was qualitatively assessed using the AWD method, which measures the diameter of the inhibition zones in millimeters. This technique involves the application of test extracts on agar plates to inhibit the growth of microorganisms (Bubonja-Šonje et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2022). The results were compared with those of the standard antimicrobial agents gentamycin (for bacteria) and fluconazole (for fungi). As presented in Table 4, the extract exhibited significant antimicrobial activity against the tested strains. For B. subtilis (ATCC6633), the extract produced an inhibition zone of 31.0 ± 0.2 mm, exceeding the 28.0 ± 0.1 mm zone observed with gentamycin.

Fig. 1. Observed mass (m/z) of the ethanolic extract: rutin (A), quercetin (B), caffeic acid (C), lut-6-C-Glu (D), lut-7-O-Glu (E), 2″-O-deoxyhex-C-Hex-Lut (F), 2″-O-deoxyhex-C-Hex-Apig (G), Api-6-C-Glu (H), 3-O-feruloyl-quinic acid (trans) (I), and 4-O-feruloyl-quinic acid (trans)) (J). Table 3. Antioxidant profile of PAEE.

Against S. aureus (ATCC6538), the extract yielded an inhibition zone of 29.0 ± 0.1 mm, which was slightly smaller than the 34.0 ± 0.2 mm zone achieved by gentamycin. The extract also demonstrated notable activity against E. coli (ATCC8739), with an inhibition zone of 20.0 ± 0.1 mm, comparable to the 19.0 ± 0.1 mm zone produced by gentamycin. In the case of K. pneumoniae (ATCC13883), the extract outperformed the standard drug, generating an inhibition zone of 24.0 ± 0.1 mm compared with 21.0 ± 0.1 mm for gentamycin. In antifungal testing, the extract showed remarkable efficacy against C. albicans (ATCC10221), producing an inhibition zone of 33.0 ± 0.1 mm, which was significantly larger than the 11.0 ± 0.1 mm zone observed with fluconazole. However, the extract exhibited no activity against M. circinelloides (AUMMC11656), as indicated in Table 4. Antiviral activity of P. australisThe in vitro antiviral activity of P. australis extracts was assessed against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) and hepatitis A virus (HAV) using the MTT assay. The MNTC was determined to be 619.16 ± 1.18 µg/ml. At their respective MNTCs, the ethanol extract exhibited notable antiviral efficacy, with 95.44% inhibition of HAV and 67.26% inhibition of HSV-1. The selectivity index (SI), determined as the cytotoxic concentration to the IC50, revealed moderate antiviral potential, with an SI value of 4.96 for both HAV and HSV-1. DiscussionTraditional medicines and many modern medicines are indirectly derived from medicinal plants, which are natural reservoirs of bioactive and therapeutic compounds that play an important role in preventing diseases and improving human health. Although modern synthetic drugs are widely used, their undesirable side effects often lead to additional pathophysiological complications (Maldonado Miranda, 2021). This has driven interest in exploring plant-based bioactive compounds as safer and more sustainable alternatives. In this context, the bioactive compounds, antioxidant potential, and antimicrobial capacity of P. australis collected from Benghazi, Libya, were studied. The phytochemical composition of P. australis was evaluated by measuring its TPC and TFC, both of which are known to combat oxidative stress-related disorders, including chronic inflammation, neoplastic diseases, cardiac disorders, and nerve degenerative disorders. The TPC (65.94 mg GAE/g) and TFC (22.7 mg RE/g) of the ethanolic extract (PAEE) were greater than those of the closely related species Miscanthus sacchariflorus with average TPC (31.97 mg GAE/g) and TFC (14.15 mg QE/g) (Ghimire et al., 2021). These findings indicate that P. australis contains abundant phenolic and flavonoid compounds, highlighting its significant biological activities. Previous studies (Unuofin et al., 2024a,b) reported that the TPC of P. australis leaves was 39.17 ± 0.65 mg GAE/g, whereas the TFC was 19.85 ± 2.64 mg QE/g. The antioxidant capacity of P. australis, with a DPPH IC50 value of 476.95 µg/ml and robust FRAP values, indicates strong radical-scavenging potential. Although its IC50 was higher than that of C. longa (27.2 µg/ ml) (Sabir et al., 2020), it was comparable to the antioxidant activity recorded in some accessions of M. sacchariflorus (Ghimire et al., 2021). The diversity of phenolic compounds in P. australis, including rutin, quercetin, and caffeic acid, complements the curcumin-dominated antioxidant profile of C. longa and demonstrates distinct antioxidant mechanisms among the three species. The antioxidant activity of P. australis is attributed to the presence of various bioactive compounds, including phenolics, flavonoids, and their derivatives, which exert their effects through diverse mechanisms. Phenolic compounds such as rutin, quercetin, caffeic acid, 3-O-feruloyl-quinic acid (trans), 4-O-feruloyl-quinic acid (trans), daidzein, and vanillin have been reported to significantly contribute to the antioxidant potential of plants. Rutin exerts its antioxidant effects by increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes, and quercetin neutralizes reactive oxygen species, protecting against oxidative stress (Luo et al., 2019) Caffeic acid has antioxidant properties primarily through iron chelation, which prevents oxidative reactions catalyzed by free iron (Genaro-Mattos et al., 2015). Feruloyl-quinic acids, such as 3-O-feruloyl-quinic acid (trans) and 4-O-feruloyl-quinic acid (trans), also contribute to antioxidant activity (Rakoczy et al., 2023). Daidzein, an isoflavone, scavenges free radicals and modulates the cellular signaling pathways involved in oxidative stress, thereby protecting against oxidative damage (Li et al., 2022). Additionally, vanillin and LUT-7-O-glucoside act as free radical scavengers and may increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes. It has been studied for its potential protective effects against oxidative stress (Rehfeldt et al., 2022; Iannuzzi et al., 2023). The antioxidant profile of P. australis highlights its potential to mitigate oxidative stress and supports its application in natural antioxidant development.

Fig. 2. Morphological changes in HepG2, Mcf7, and Caco2 cells treated with different concentrations of PAEE.

Fig. 3. Graphs showing the viability and toxicity of effect of PAEE in HepG2, Mcf7, and Caco2 cells at different concentrations.

Fig. 4. Cytotoxicity effect of PAEE on HepG2, Mcf7, and Caco2 cells at different concentrations. Values are presented as mean + standard error. Table 4. In vitro antimicrobial activity assay (inhibition zones in mm).

LC–MS analysis revealed notable differences in the phytochemical profiles of the plants. Phragmites australis contains a broad spectrum of phenolic acids and flavonoids, including unique compounds such as 3-O-feruloyl-quinic acid and LUT glycosides. In contrast, M. sacchariflorus predominantly featured p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and chlorogenic acid (Ghimire et al., 2021) In contrast with the P. australis water extract reported by Unuofin et al. (2024a,b), which did not noticeably reduce the viability of human breast (MCF-7) and lung (A549) cancer cell lines, the PAEE had significant IC50 values (9.61 ± 0.13 µg/ml for HepG2, 21.44 ± 0.29 µg/ml for Caco-2, and 23.48 ± 0.24 µg/ml for MCF-7 cells) and morphological alterations, particularly in MCF-7 and Caco-2 cells, indicating greater sensitivity (p ≤ 0.05). These results can be attributed to LUT-7-O-glucoside, which has a potent cytotoxic effect and low toxicity against normal cells (high SI) (Goodarzi et al., 2020), the cytotoxic effect of LUT involves multiple mechanisms, primarily through the induction of DNA damage and disruption of cellular functions at higher concentrations (Muruganathan et al., 2022). Additionally, daidzein, which has an anticancer effect, may also contribute to these effects (Uğur Kaplan et al., 2022). Phragmites australis exhibited significant antimicrobial efficacy against bacterial and fungal strains, with inhibition zones comparable to or exceeding those of standard antibiotics, which was ascribed to its phenolic and flavonoid contents. Through their distinct mechanisms, quercetin, rutin, caffeic acid, and LUT-7-O-glucoside contribute to the antimicrobial effects of P. australis (Álvarez-Martínez et al., 2021). In line with the results of a recent study by Unuofin et al. (2024a,b), our study also revealed the strong inhibitory effects of P. australis against gram-positive bacteria and C. albicans, confirming the broad-spectrum antimicrobial potential of this plant. There are only a few reports on the antiviral effects of P. australis, especially against HAV and HSV-1. Our results showed that the extracts had a significant inhibitory effect on viral replication. ConclusionThis study is the first to investigate P. australis from Benghazi, Libya, revealing its rich diversity of polyphenols and flavonoids, along with its strong antioxidant, antibacterial, and antiviral activities. Further complementary methods and in-depth studies are recommended to build on these findings and advanced research on this promising plant. AcknowledgmentsThis study was funded by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research through the Research Unit “Valorization of Actives Biomolecules” at the Higher Institute of Applied Biology, University of Gabes. Additional support was provided by the Faculty of Science of Bizerte, University of Carthage, Jarzouna, Tunisia; the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benghazi; and the Research Unit of the Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Benghazi. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the findings presented in this paper. FundingThis research did not receive external or internal funding. Authors’ contributionsLazhar Zourgui: Main supervision and guidance on experimental design, interpretation of results, and critical revision of the manuscript. Sara A. Abdulla: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, laboratory experiments, formal analysis, and manuscript preparation. Farag A. Elshaari: Second supervision, guidance on experimental design, and critical revision of the manuscript. Mohamed Alshintari: Support in plant identification. All authors have thoroughly reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication. Data availabilityThe data are available from the corresponding author upon request. ReferenceAbdelaziz, A.M., Abdel-Maksoud, M.A., Fatima, S., Almutairi, S., Kiani, B.H. and Hashem, A.H. 2024. Anabasis setifera leaf extract from arid habitat: a treasure trove of bioactive phytochemicals with potent antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties. PLoS One 19(10), e0310298. Abd-El-Aziz, N.M., Hifnawy, M.S., Lotfy, R.A. and Younis, I.Y. 2024. LC/MS/MS and GC/MS/MS metabolic profiling of Leontodon hispidulus, in vitro and in silico anticancer activity evaluation targeting hexokinase 2 enzyme. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6872. Acidri, R., Sawai, Y., Sugimoto, Y., Handa, T., Sasagawa, D., Masunaga, T., Yamamoto, S. and Nishihara, E. 2020. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant capacity of coffee plant organs compared to green and roasted coffee beans. Antioxidants (Basel) 9(2), 93. Álvarez-Martínez, F.J., Barrajón-Catalán, E., Herranz- López, M. and Micol, V. 2021. Antibacterial plant compounds, extracts and essential oils: an updated review on their effects and putative mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine 90, 153626. Athamena, S., Laroui, S., Bouzid, W. and Meziti, A. 2019. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities of Juniperu thurifera. J. Herb. Spices Med. Plants. 25(3), 271–286. Benzie, I.F.F. and Strain, J.J. 1996. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 239(1), 70–76. Boly, R., Lamkami, T., Lompo, M., Dubois, J. and Guissou, I. 2016. DPPH free radical scavenging activity of two extracts from agelanthus dodoneifolius (Loranthaceae) leaves. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 8(1), 29–34. Bubonja-Šonje, M., Knezević, S. and Abram, M. 2020. Challenges to antimicrobial susceptibility testing of plant-derived polyphenolic compounds. Arh. Hig. Rada. Toksikol. 71(4), 300–311. Chang, S.F., Hsieh, C.L. and Yen, G.C. 2008. The protective effect of Opuntia dillenii Haw fruit against low-density lipoprotein peroxidation and its active compounds. Food Chem. 106(2), 569–575. Chen, H., Landen, C.N., Li, Y., Alvarez, R.D. and Tollefsbol, T.O. 2013. Enhancement of cisplatin- mediated apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells through potentiating G2/M arrest and p21 upregulation by combinatorial epigallocatechin gallate and sulforaphane. J. Oncol. 2013, 872957. Cui, J., Qiu, T., Li, L. and Cui, S. 2023. De novo full- length transcriptome analysis of two ecotypes of Phragmites australis (swamp reed and dune reed) provides new insights into the transcriptomic complexity of dune reed and its long-term adaptation to desert environments. BMC Genom. 24(1), 180. El Gendy, A.E.N.G., Essa, A.F., El-Rashedy, A.A., Elgamal, A.M., Khalaf, D.D., Hassan, E.M., Abd- ElGawad, A.M., Elgorban, A.M., Zaghloul, N.S., Alamery, S.F. and Elshamy, A.I. 2022. Antiviral potentialities of chemically characterized essential oils of Acacia nilotica bark and fruits against hepatitis A and herpes simplex viruses: in vitro, in silico, and molecular dynamics studies. Plants 11(21), 2889. Espinel-Ingroff, A., Arthington-Skaggs, B., Iqbal, N., Ellis, D., Pfaller, M.A., Messer, S., Rinaldi, M., Fothergill, A., Gibbs, D.L. and Wang, A. 2007. Multicenter evaluation of a new disk agar diffusion method for susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi with voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole, amphotericin B, and caspofungin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45(6), 1811–1820. Espinel-Ingroff, A., Canton, E., Fothergill, A., Ghannoum, M., Johnson, E., Jones, R.N., Ostrosky- Zeichner, L., Schell, W., Gibbs, D.L., Wang, A. and Turnidge, J. 2011. Quality control guidelines for amphotericin B, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole disk diffusion susceptibility tests with non supplemented Mueller-Hinton Agar (CLSI M51-A Document) for non dermatophyte filamentous Fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49(7), 2568. Falzon, C.C. and Balabanova, A. 2017. Phytotherapy: an introduction to herbal medicine. Prim. Care. 44(2), 217–227. Fang, M., Kong, L.Y., Ji, G.H., Pu, F.L., Su, Y.Z., Li, Y.F., Moore, M., Willcox, M., Trill, J., Hu, X.Y. and Liu, J.P. 2024. Chinese medicine Phragmites communis (Lu Gen) for acute respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. 15, 1242525. Genaro-Mattos, T.C., Maurício, Â.Q., Rettori, D., Alonso, A. and Hermes-Lima, M. 2015. Antioxidant activity of caffeic acid against iron-induced free radical generation—a chemical approach. PLoS One 10(6), e0129963. Ghimire, B.K., Sacks, E.J., Kim, S.H., Yu, C.Y. and Chung, I.M. 2021. Profiling of phenolic compounds composition, morphological traits, and antioxidant activity of Miscanthus sacchariflorus L. accessions. Agronomy 11(2), 243. Goodarzi, S., Tabatabaei, M.J., Mohammad Jafari, R., Shemirani, F., Tavakoli, S., Mofasseri, M. and Tofighi, Z. 2020. Cuminum cyminum fruits as source of luteolin- 7-O-glucoside, potent cytotoxic flavonoid against breast cancer cell lines. Nat. Prod. Res. 34(11), 1602–1606. Hossain, M.L., Lim, L.Y., Hammer, K., Hettiarachchi, D. and Locher, C. 2022. A review of commonly used methodologies for assessing the antibacterial activity of honey and honey products. Antibiotics (Basel) 11(7), 975. Iannuzzi, C., Liccardo, M. and Sirangelo, I. 2023. Overview of the role of vanillin in neurodegenerative diseases and neuropathophysiological conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(3), 1817. Jagetia, G.C. and Baliga, M.S. 2004. The evaluation of nitric oxide scavenging activity of certain Indian medicinal plants in vitro: a preliminary study. J. Med. Food 7(3), 343–348. Li, Y., Jiang, X., Cai, L., Zhang, Y., Ding, H., Yin, J. and Li, X. 2022. Effects of daidzein on antioxidant capacity in weaned pigs and IPEC-J2 cells. Anim. Nutr. 11, 48–59. Luo, M., Tian, R., Yang, Z., Peng, Y. and Lu, N. 2019. Quercetin suppressed NADPH oxidase-derived oxidative stress via heme oxygenase-1 induction in macrophages. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 671, 69–76. Maldonado Miranda, J.J. 2021. Medicinal plants and their traditional uses in different locations. In Phytomedicine. Eds., Bhat, R.A., Dervash, M.A. and Hakeem, K.R. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier, pp: 207–223. Molole, G.J., Gure, A. and Abdissa, N. 2022. Determination of total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Commiphora mollis (Oliv.) Engl. resin. BMC Chem. 16(1), 48. Muruganathan, N., Dhanapal, A.R., Baskar, V., Muthuramalingam, P., Selvaraj, D., Aara, H., Abdullah, M.Z.S. and Sivanesan, I. 2022. Recent updates on source, biosynthesis, and therapeutic potential of natural flavonoid luteolin: a review. Metabolites 12(11), 1145. Pedro, S.I., Fernandes, T.A., Luís, Â., Antunes, A.M.M., Gonçalves, J.C., Gominho, J., Gallardo, E. and Anjos, O. 2023. First chemical profile analysis of acacia pods. Plants (Basel) 12(19), 3486. Prieto, P., Pineda, M. and Aguilar, M. 1999. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phospho molybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem. 269(2), 337–341. Rakoczy, K., Kaczor, J., Sołtyk, A., Szymańska, N., Stecko, J., Sleziak, J., Kulbacka, J. and Baczyńska, D. 2023. Application of luteolin in neoplasms and nonneoplastic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(21), 15995. Rehfeldt, S.C.H., Silva, J., Alves, C., Pinteus, S., Pedrosa, R., Laufer, S. and Goettert, M.I. 2022. Neuroprotective effect of luteolin-7-O- glucoside against 6-OHDA-induced damage in undifferentiated and RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(6), 2914. Sabir, S.M., Zeb, A., Mahmood, M., Abbas, S.R., Ahmad, Z. and Iqbal, N. 2020. Phytochemical analysis and biological activities of ethanolic extract of Curcuma longa rhizome. Braz. J. Biol. (3), 737–740. Salam, A.M. and Quave, C.L. 2019. Medicinal plants as a reservoir of new structures for anti-infective compounds. Antibacterial drug discovery to combat MDR: natural compounds, nanotechnology and novel synthetic sources. Singapore: Springer, Singapore Publishers, pp: 277–298. Shraim, A.M., Ahmed, T.A., Rahman, M.M. and Hijji, Y.M. 2021. Determination of total flavonoid content by aluminum chloride assay: a critical evaluation. LWT 150, 111932. Siddiqui, N., Rauf, A., Latif, A. and Mahmood, Z. 2017. Spectrophotometric determination of the total phenolic content, spectral and fluorescence study of the herbal Unani drug Gul-e-Zoofa (Nepeta bracteata Benth). J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 12(4), 360–363. Tiama, T.M., Ibrahim, M.A., Sharaf, M.H. and Mabied, A.F. 2023. Effect of germanium oxide on the structural aspects and bioactivity of bioactive silicate glass. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9582. Uğur Kaplan, A.B., Öztürk, N., Çetin, M., Vural, I. and Özer, T.Ö. 2022. The nanosuspension formulations of Daidzein: preparation and in vitro characterization. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 19(1), 84–92. Unuofin, J.O., Oladipo, A.O., More, G.K., Adeeyo, A.O., Mustapha, H.T., Msagati, T.A.M. and Lebelo, S.L. 2024a. Phytochemical profiling of Phragmites australis leaf extract and its nano-structural antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 34(10), 4509–4523. Unuofin, J.O., Oladipo, A.O., More, G.K., Adeeyo, A.O., Mustapha, H.T., Msagati, T.A.M. and Lebelo, S.L. 2024b. Phytochemical profiling of Phragmites australis leaf extract and its nano-structural antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 34(10), 4509–4523. van de Loosdrecht, A.A., Beelen, R.H.J., Ossenkoppele, G.J., Broekhoven, M.G. and Langenhuijsen, M.M.A.C. 1994. A tetrazolium-based colorimetric MTT assay to quantitate human monocyte mediated cytotoxicity against leukemic cells from cell lines and patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J. Immunol. Methods. 174(1-2), 311–320. van de Sand, L., Bormann, M., Schmitz, Y., Heilingloh, C.S., Witzke, O. and Krawczyk, A. 2021. Antiviral active compounds derived from natural sources against herpes simplex viruses. Viruses 13(7), 1386. Wakeel, A., Jan, S.A., Ullah, I., Shinwari, Z.K. and Xu, M. 2019. Solvent polarity mediates phytochemical yield and antioxidant capacity of Isatis tinctoria. PeerJ 2019(10), e7857. Yan, Y.B., Tian, Q., Zhang, J.F. and Xiang, Y. 2020. Antitumor effects and molecular mechanisms of action of natural products in ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 20(5), 141. Zourgui, M.N., Hfaiedh, M., Brahmi, D., Affi, W., Gharsallah, N., Zourgui, L. and Amri, M. 2020. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Opuntia streptacantha fruit skin. J. Food Meas. Charact. (4), 2721– 2733. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Abdulla SA, Elshaari FA, Alshintari M, Zourgui L. Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 Web Style Abdulla SA, Elshaari FA, Alshintari M, Zourgui L. Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=239069 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Abdulla SA, Elshaari FA, Alshintari M, Zourgui L. Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Abdulla SA, Elshaari FA, Alshintari M, Zourgui L. Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 Harvard Style Abdulla, S. A., Elshaari, . F. A., Alshintari, . M. & Zourgui, . L. (2025) Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 Turabian Style Abdulla, Sarah A., Farag A. Elshaari, Mohamed Alshintari, and Lazhar Zourgui. 2025. Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 Chicago Style Abdulla, Sarah A., Farag A. Elshaari, Mohamed Alshintari, and Lazhar Zourgui. "Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Abdulla, Sarah A., Farag A. Elshaari, Mohamed Alshintari, and Lazhar Zourgui. "Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2478-2491. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Abdulla, S. A., Elshaari, . F. A., Alshintari, . M. & Zourgui, . L. (2025) Phytochemical profiling and biological activity of the ethanolic extract of Phragmites australis. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2478-2491. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.20 |