| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2439-2448 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2439-2448 Research Article Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in ZambiaRubaijaniza Abigaba1,2*, Edwell S. Mwaanga3, Pharaoh Collins Sianangama1, Progress H. Nyanga4 and Wilson N. M. Mwenya11Department of Animal Science, School of Agricultural Sciences, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia 2Department of Comparative Anatomy and Physiological Sciences, School of Biosecurity, Biotechnology, and Laboratory Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 3Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia 4Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences, School of Natural Sciences, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia * Correspondence to: Rubaijaniza Abigaba. Department of Animal Science, School of Agricultural Sciences, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia; Department of Comparative Anatomy and Physiological Sciences, School of Biosecurity, Biotechnology, and Laboratory Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email: abigabajzan [at] gmail.com / rubaijaniza.abigaba [at] mak.ac.ug Submitted: 25/01/2025 Revised: 24/04/2025 Accepted: 08/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

AbstractBackground: Pigs contribute to the livelihoods of traditional pig farmers (TPFs) through meat production and economic gains. However, the production of pigs, particularly genotypes indigenous to Zambia, remains suboptimal, largely due to dominance of the traditional farming practice. To actualize full productivity and contribute to increased pig numbers, the application of artificial insemination (AI) and related reproductive biotechnologies has been recommended. However, the successful application of these biotechnologies requires knowledge of animal biology. Aim: This study investigated the semen attributes of Lusitu boars as an initial step toward successful biotechnology applications. Methods: A two-stage nested design was used with a total of 60 ejaculates analyzed to generate data. The data were analyzed descriptively using means and standard deviations, while the inferential statistics included ANOVA and correlation coefficients. Results: The mean scores for analyzed parameters, including semen volume, pH, sperm concentration, semen doses, vitality, total motility, and progressive motility, were above or within the recommended limits for fresh boar semen. Lusitu boar semen (LBS) scored higher (p < 0.05) in vitality and pH but significantly lower (p < 0.05) in volume, sperm concentration, and semen doses compared with the Large White genotype. The mean scores of sperm abnormality indices and motility traits were generally similar (p > 0.05) between the two boar genotypes. The boar effect was significant on semen volume, pH, and motility (p < 0.05). Despite multiple correlations observed for some traits, no characteristic correlated with all studied traits. Conclusion: Characterization of indigenous Lusitu boars by their semen attributes revealed that this genotype produced semen whose quality parameter scores were above/within limits/range acceptable for fresh boar semen. In addition, each genotype had some areas of strength over the other, although the Large White generally performed better. The indigenous Lusitu boar may perform with desirable results when reproductive biotechnology is applied, particularly the AI program. Keywords: Artificial insemination, Biotechnology, Lusitu boar, Semen characteristics, Semen quality.. IntroductionPigs offer great support to livestock farmers due to their high prolificacy, short generational interval, and small capital investment (Shylesh et al., 2019). Farmers in Zambia rear them largely for income generation and meat for home consumption (Abigaba et al., 2022a). The majority (>80%) of farmers in this country rear pigs under a traditional farming system (TFS) that is devoid of methods and strategies to actualize their full productivity (Phiri et al., 2013). Thus, there is a glaring need to increase the productivity and production of pigs, particularly indigenous genotypes. Lusitu and Nsenga pigs are the indigenous genotypes reared in this country and constitute the majority (>65%) of the national flock size (MACO, 2003). The TPFs value these pigs because of their considerable good performance under poor management and environmental stress. This holds true, especially for Lusitu pigs, which originate and are distributed widely in the hottest area of Zambia by far (Abigaba et al., 2022a). Although indigenous Lusitu pigs are adapted to existing farming conditions, the effects of climate change, nutritional stress, uncontrolled cross and inbreeding, and diseases such as African swine fever compromise the realization of their full-productivity and production potential (Phiri et al., 2013). According to Nigatu (2018), the negative effects of these adverse factors can be reduced through the adoption of improved management practices, including reproductive biotechnology applications (Nigatu, 2018). The appropriate biotechnology is artificial insemination (AI) since it is cost-effective and can overcome most constraints in the TFS (Phiri et al., 2013; Dotché et al., 2021; Govindasamy et al., 2021). In this case, there is urgency and need for the application of AI in this country. A previous study confirmed the positive attitudes of farmers toward the application of AI and related reproductive biotechnologies; however, these have not been applied, particularly for indigenous pig production (Abigaba et al., 2022b). Moreover, the effectiveness of AI in local setups requires the use of locally produced semen, avoiding the importation and storage of semen from foreign breeds (Dotché et al., 2021). The success rate of AI is largely dependent on the soundness or reproductive aptitude of the boar used, which, in turn, depends on its semen quality and quantity characteristics (Chakurkar et al., 2016; Savić et al., 2017). Examples of such characteristics are semen volume, sperm concentration, morphology, and percentage of sperm with correct motility, inter alia (Chakurkar et al., 2016; Kondracki et al., 2017). However, no previous studies have characterized the indigenous Lusitu genotype according to its semen quality and quantity characteristics. In this regard, little is known about the reproductive status of this pig genotype. There is a need to characterize indigenous pigs of Zambia, including the Lusitu genotype, particularly by their semen characteristics. Additionally, some earlier studies (Charneca et al., 2007; Chakurkar et al., 2016; Suárez-Mesa et al., 2021) recommended research on indigenous pigs as an initial step to facilitate successful biotechnology application as well as their conservation. The current study aimed to characterize Lusitu boars by their semen attributes in terms of their contribution to improved production of these pigs through the application of AI and related biotechnologies. The objectives of this study were to (1) determine the quantity and quality characteristics of semen from indigenous Lusitu pigs reared in Zambia, (2) compare the semen characteristics of these pigs with those of the Large White genotype reared in Zambia, and (3) evaluate the quality of semen from indigenous Lusitu boars for potential utilization for AI purposes. Materials and MethodsExperimental Animals and ManagementThe experimental animals were physically healthy and sexually mature. These pigs were sourced from Gwembe and Lusaka Districts of Zambia, including six Zambian Lusitu (Lusitu) and five Large White boars, respectively. The indigenous Lusitu boars weighed 69.56 ± 2.92 kg on average, while their Large White counterparts weighed 162.20 ± 10.14 kg. The average age for indigenous Lusitu and Large White boars was 19.60 and 18.00 months, respectively. The boars were housed in individual pens with sufficient ventilation and ambient temperature ranging from 19°C to 33°C. Regarding feeding, both Lusitu and Large White boars were provided with boar mash (Novatek animal feeds, Lusaka, Zambia) in the proportions of 1 and 2 kg, respectively, on a daily basis. This feed was provided to boars in solid form and in two halves: one in the morning and the other in the evening. Water was provided ad libitum from the water troughs. Experimental DesignThe study employed a two-factor nested design with two factors, namely breed as the fixed factor and boar nested within the breed as the random factor. The fixed factor had two levels consisting of the Lusitu and Large White genotypes. In addition, it was the main factor of interest in the current study. Ejaculates were randomly collected from boars under study, hence the consideration of boars as a random factor in the study. The ejaculates were considered subjects in this study. At least five replicate collections were conducted for each boar, which in total constituted 60 ejaculates (sample size). The current study relied on a positivist paradigm, with hypothesis testing considered for knowledge generation and/or generalization of findings. For data collection, ejaculates were obtained from both Lusitu and Large White boars, followed by evaluation for different quality parameters, including volume, pH, sperm concentration, vitality, morphology, and their derivatives. Semen Collection and EvaluationThe collection of ejaculates from both groups was performed using the gloved hand method (King and Macpherson, 1973). To do this, the dummy sow (Futai, Dummy sow, Hebei, China) as well as live sows on heat, for those that failed to mount the dummy sows, were used. Once collected, each ejaculate was evaluated for semen traits using standard procedures as follows. Semen Volume and pHThe volume was determined by gently transferring the collected semen sample from the semen collection flask into a 250-ml pre-heated (37°C) measuring cylinder (Shylesh et al., 2019). The ejaculate pH was measured using a handheld pH meter (Testo 206-pH2, Testo SE & Co. KGaA, UK). The measurement range of the pH meter, its accuracy, and resolution were 0–14, ± 0.02, and 0.01, respectively. The measurement of semen pH was performed based on an earlier procedure (Ratchamak et al., 2019). Sperm ConcentrationSperm concentration was evaluated using a motility module of the Sperm Class Analyzer® (SCA), version 6.0 (Microptic S.L., Barcelona, Spain). To obtain this concentration, approximately 3.5 μl of semen was pre-diluted with phosphate buffer saline (PBS; Sigma Aldrich, st. Louis, MO, USA) and loaded into the pre-heated (37°C) chamber (20 μm deep) of the Leja-4 chamber slide (Leja Products B.V., Nieuw Vennep, The Netherlands) using a positive displacement pipette. The procedure for determination of sperm concentration (sperm/ml) was based on a previous study (Van der Horst and Maree, 2009), while the settings used were adopted from the SCA manufacturer. The total number of sperm (total sperm per ejaculate) was determined by multiplying the total volume of gel-free ejaculate (ml) by the sperm concentration (Althouse et al., 2015). Sperm MotilityBoth total motility and progressive motility were determined using the CASA-Mot module (SCA, version 6 (Microptic S.L., Barcelona, Spain). Parameter evaluation followed an earlier procedure (Masenya et al., 2011; Karageorgiou et al., 2016), whereas the module settings for boar semen were adopted from the SCA manufacturer. Motility evaluation was performed using semen diluted to about 20–35 × 106 sperm/ml. Semen dilution was performed using PBS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). At least two fields, including a minimum of 500 motile sperm (trajectories) in total, were captured for each sample (×100) before taking the readings for sperm concentration. Sperm VitalityThe evaluation of sperm vitality relied on the dye exclusion approach, in which a modified Eosin/Nigrosin dye (Brightvit®, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa) was used for this study. The CASA, with a semiautomatic SCA counter program or software (SCA®, Microptic SL, Barcelona, Spain), was used to determine the proportions of viable and nonviable sperm. The procedure for parameter determination was based on that of Brightvit® manufacturer. Sperm MorphologyComputer-aided sperm morphology analysis (CASMA), which automatically detects the acrosome, head, and midpiece of sperm, was used to evaluate the morphological forms of sperm. The analysis was done on sperm following appropriate smear preparation and staining with a SpermBlue stain-fixative mixture (Microptic SL, Barcelona, Spain) (Van der Horst and Maree, 2009), as modified by Ngcauzele (2018). For each sample, smear preparation and analysis were performed in duplicates, and the average of the two observations was recorded as a single datum. Statistical AnalysisAll the data were analyzed in SPSS IBM® (SPSS IBM 26 version, USA). The data were checked for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, while homogeneity of variance was tested using Lavene’s test. Non-normally distributed data were subjected to log or square root transformations before analysis, but the means and standard deviations (SD) are reported as untransformed to ease comparisons with findings from other studies. Means and SD were the descriptive statistics used, whereas ANOVA and correlations were the inferential statistics employed. The F-test in ANOVA (two-way nested ANOVA) was used to test the effect of breed on all semen characteristics, except sperm morphology. In the Generalized linear model (GLM, univariate), breed and boar factors were treated as fixed and random factors, respectively. The nested ANOVA statistical model used to explain the variation in a response Y was: Yijk=μ+αi+βj(i)+eijk Where, Yijk is the dependent variable representing the semen characteristic, μ indicates the overall mean, αi denotes the main effect of breed factor with two levels (i = Large White and Lusitu genotypes), βj(i) represents the main effect of the boar nested within the breed, and eijk is the error term with k being the number of replicate observations within each area i, j. The morphological traits of sperm from the two pig genotypes were analyzed using Fisher’s and Welch’s one-way ANOVA tests, with the breed being the main factor. Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients were also calculated for parameter correlations. In all the tests, significance was taken at p < 0.05. Ethical ApprovalThis study was approved in April, 2021, by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Zambia (UNZABREC), with approval number 1595-2021. The management of animals and experiment procedures was carried out with strict supervision by the Departmental Research Committee. ResultsSemen Characteristics of Indigenous Zambian Lusitu BoarsThe results for selected characteristics of semen from indigenous Lusitu boar genotype are presented in Table 1. The average volume of semen collected was 103.60 ml, and its average pH was 7.50. The sperm concentration in the ejaculate was 27.87 × 109 sperm/ ml. Each boar produced approximately nine semen doses when a threshold of 3.0 × 109 sperm per dose was considered. This study found that freshly collected semen contained an average of 82.41% of live sperm. The mean total and progressive motility scores were 92.82% and 79.40%, respectively. Additionally, 73.90% of the sperm in freshly processed LBS exhibited normal morphology. The abnormality index check revealed a mean SDI score of 0.3. Table 1. Semen characteristics of indigenous Zambian Lusitu boars.

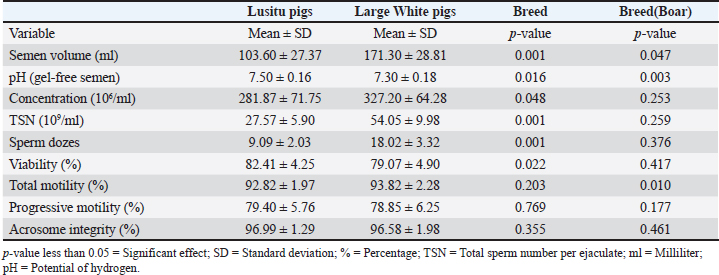

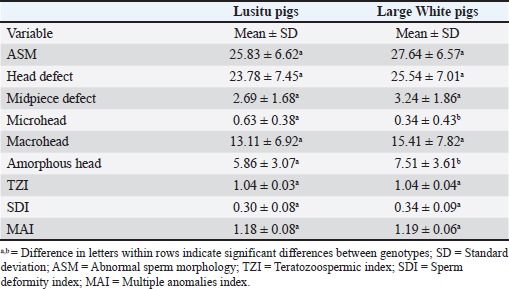

Mean Semen Characteristics Scores of Lusitu and Large White Pigs Reared in ZambiaThe results of semen and/or sperm characteristics for the Lusitu and Large White genotypes are shown in Table 2. The indigenous Lusitu boars scored lower than the Large white in terms of the volume of gel-free semen, sperm concentration, total sperm number, and semen doses (p < 0.05). Gel-free semen from Lusitu pigs had a significantly higher (p < 0.05) pH and proportion of live sperm in semen than the Large White. The proportions of motile sperm in semen from both genotypes were generally similar (p > 0.05), and similar findings were observed for progressive motility (p > 0.05). The effect of boar was significant (p < 0.05) on semen pH, volume, and total motility (p < 0.05), while the effect on other semen traits indicated no significance (p > 0.05). Means for Morphological Traits of semen in Lusitu Compared With those of Large White Pigs Reared in ZambiaThe semen quality scores of selected morphological traits are presented for each studied pig genotype (Table 3). The mean abnormal sperm morphology values did not differ significantly (p > 0.05). The observed proportions of sperm in semen from both pig genotypes were similar in terms of head and midpiece defects (p > 0.05). No significant differences were observed between mean macrohead values (p > 0.05). The proportions of sperm with microhead defects were higher in Lusitu (p > 0.05) than in Large White, whereas the proportion of amorphous heads was significantly lower (p < 0.05). The observed teratozoospermic, multiple anomalies, and sperm deformity indices did not significantly differ between the two groups (p > 0.05). Correlations Between Selected Semen Characteristics of Indigenous Lusitu PigsThe correlation results between various semen traits are presented in Table 4. This study revealed a negative relationship between pH and other semen traits that were generally nonsignificant, except for NSM and SAI (p > 0.05). Semen volume was significantly correlated with sperm concentration (p < 0.05) and total sperm (p < 0.05). The concentration of sperm was also correlated with total sperm (p < 0.05), but with a nonsignificant weak relationship with SDI and vitality (p > 0.05). The relationship between motility and most of the studied traits was weak and nonsignificant (p > 0.05). The SDI’s relationship with most of the characteristics was generally negative and non-significant (p > 0.05), except for NSM (p < 0.05). Vitality was significantly correlated with SAI (p < 0.05). DiscussionPrediction of boar fertility aptitude is done through evaluation of semen quality and quantity characteristics, including semen volume, sperm concentration, motility, morphology, inter alia (Kondracki et al., 2017). This study confirmed that the pH of semen in indigenous Lusitu boars was within the normal pH range (7.2–7.5) acceptable for freshly ejaculated boar semen (Johnson et al., 2000). However, a disparity was observed between the pH of Lusitu boar semen (7.50) and that of the Large White (7.30), which was probably due to a genetic effect and/or variations in the contribution(s) from the specific accessory sexual gland(s) to the ejaculate. This is in view of the effect of specific accessory sexual gland contribution(s) on the volume of ejaculates collected (Frunză et al., 2008; Bonet et al., 2012), which, in turn, may influence ejaculate constituents as well as the semen pH. Semen pH is an important indicator of seminal material quality. The current findings indicated normal fresh semen in Lusitu boars, as the observed pH value was much below 8. According to Frunză et al. (2008), a pH value above 8 is a sign of infection in the genital tract or accessory sexual glands and/or low semen quality (Frunză et al., 2008). Moreover, a premature increase in semen pH may increase mitochondrial activity, which, in turn, shortens the life span of sperm following depletion of the ATP (adenosine triphosphate) stores (Purdy et al., 2010). Table 2. Mean scores for semen characteristics of Lusitu and Large White boars in Zambia.

Table 3. Morphological quality of semen in Lusitu and Large White pigs reared in Zambia.

The observed mean volume of Lusitu boar semen was lower than the previously reported range (150–300 ml) (Bonet et al., 2013), which was probably due to the small body size of the animals and/or the use of live sows during semen collection. The effect of body size on the volume of semen produced was reported in some other studies (Chakurkar et al., 2016; Dotché et al., 2021). Additionally, the period of time live sows stood still for boars to ejaculate varied, which perhaps impacted on semen volume. All Lusitu boars failed to mount the dummy sow, a situation that probably did not allow boars to complete the ejaculation process. Nevertheless, the average volume of semen from Lusitu pigs was way above the minimum value (≤ 50 ml) required for mechanical stimulation of uterine contractions (Gerfen et al., 1994). Moreover, the observed mean score was generally higher than the case of indigenous pigs in other countries (Chakurkar et al., 2016; Dotché et al., 2021) but significantly lower compared to the large white genotype. Similarly, the sperm concentration was lower in indigenous Lusitu than in the Large White boars, which disagreed with Masenyi et al. (2011) who did not find a difference between the South African Kolbroek and Large White boars. Nevertheless, variations in sperm concentration between pig breeds have also been reported in other studies (Kommisrud et al., 2002; Pizzi et al., 2005; Jaishankar et al., 2018). On the other hand, the current study did not show a boar effect on the concentration of sperm, which was consistent with the results of an earlier study (Shylesh et al., 2019). Sperm concentration is an important parameter of semen quality and is routinely relied upon to determine the dilution rate and/ or number of doses derived from the collected semen (Frunză et al., 2008). In this case, the observed sperm concentration in Lusitu boars was above the acceptable minimum value (0.2 × 109 sperm/ml) (Sonderman and Luebbe, 2008; Bonet et al., 2013). Table 4. Correlation between the semen traits of indigenous Zambian Lusitu boars.

The mean total sperm (TSN) of Lusitu pigs was within the acceptable range of 10–100 × 109 sperm per ejaculate (Rozeboom, 2000). According to Althouse et al. (2015), > 15 × 109 sperm/ejaculate are required for a boar to be accepted/selected for AI or breeding purposes. Despite the observed lower score than the Large White, the mean TSN for Lusitu boars was comparable to those reported in earlier findings on an improved pig breed in Benin (Dotché et al., 2021). In addition, Lusitu boars scored higher (27.57 ± 1.53 × 109 sperm/ml) than those of the Beninese indigenous (6.2 ± 3.6 × 109 sperm/ml) and Agonda Goan pigs (10.79 ± 1.53 × 109 sperm/ml), which was probably due to differences in testicular size (Chakurkar et al., 2016; Dotché et al., 2021). The TSN for indigenous Lusitu boars points to a possiblity of this genotype undergoing some level of genetic dilution resulting from uncontrolled breeding. This is in view of a previous study in Nigeria, which confirmed that indigenous and Large White pigs suffered a considerable level of genetic dilution (Ndofor-Foleng et al., 2014). This notwithstanding, the calculated average number of semen doses from Lusitu boar semen was generally acceptable when a threshold of 3.0 × 109 sperm/per dose was considered. Indeed, this number would be even higher with a threshold of 2.0–2.5 × 109 sperm/ per dose, as suggested by Knox (2016). According to this researcher, a single boar ejaculate can be extended and used to inseminate 10–20 females. This confirms the suitability of semen from Lusitu boars for use in AI or breeding programs. Therefore, the use of Lusitu boar semen for AI or breeding can increase genetic progress on or between the swine farm(s). The current study confirmed the acceptability of Lusitu boar semen considering the 10%–40% proportion of dead cells allowed in fresh boar semen from healthy individuals (Sancho et al., 2004; Roca et al., 2016). Additionally, it was found that pig genotype influenced the vitality scores (p < 0.05), which was consistent with those of previous studies (Pizzi et al., 2005; Masenya et al., 2011; Jaishankar et al., 2018). The score difference with previous studies was probably attributed to a disparity in the time period allowed for sperm-reagent reaction and the strictness of the cut-off used to decide on viable and non-viable sperm. A longer time of sperm exposure to eosin can lead to their demise and, in turn, reduce the vitality value (Van der Horst, 2017). Despite this potential drawback, the use of eosin-nigrosin (Brightvit®) remains crucial for differentiating sperm that are motile or immotile but viable from those dead ones (BjoÈrndahl et al., 2003). In addition, human handling and season could be potential contributors to such deviations from previous reports (Shylesh et al., 2019). The determination of vitality is crucial considering that sperm can fertilize the ovum only when they are alive. This study has not established whether higher vitality scores for Lusitu compared to the Large White connote superiority in terms of fertility or survivability and resistance of the former to stressful conditions. Hence, future studies are needed to clarify this matter. Sperm motility traits are routinely relied upon to predict the potential of semen fertility, particularly the fertilizing potential, and semen dose estimation (Bonet et al., 2012; Savić et al., 2013). High motility is preferred because it enables sperm to reach the fertilization site and penetrate the oocyte (Bamundaga et al., 2018). The Lusitu boar score in terms of total motility was above the recommended minimum value (70%) (Althouse et al., 2015). Moreover, similar mean total motility scores were observed between the two genotypes, supporting the findings of Masenya et al. (2011) and Bamundaga et al. (2018). The current total motility results are an indication of active metabolism in sperm from the study boars as well as intactness of their plasma membranes (Johnson et al., 2000; Masenya et al., 2011). Regarding progressive motility, the current findings were within the acceptable cut-off score/range of 70%–95% (Rozeboom, 2000). Coincidentally, the scores for Lusitu boars were numerically similar to the mean scores previously reported in Uganda (Bamundaga et al., 2018) and Slovenia (Frunză et al., 2008), 76.85% and 75.64%–78.04%, respectively. This parameter is the most frequently used motility characteristic during boar semen evaluations (Rozeboom, 2000). Progressive motility evaluation is simple and inexpensive to conduct, with the reliable prediction of fertility, and may be useful for semen quality checks in Lusitu boars. The fertility of boar semen bears a high degree of relationship with various abnormalities of sperm (Kanshi et al., 2011). For example, acrosome abnormalities are associated with infertility (Kanshi et al., 2011). The mean normal acrosome values in the current study were above the minimum percentage (51%) acceptable for boar semen (Comizzoli et al., 2000), probably due to the freshness of the semen evaluated. The observed proportions (96.99% ± 1.29%) compared with the threshold value (> 51%) were suggestive of non-premature acrosome reactions as well as their potential stability to liquid storage effects following preservation of semen from Lusitu boars. Acrosome damage increases with storage time; hence, considerable time may elapse before the percentage of acrosome integrity falls below the 51% mark (Pursel et al., 1973; Shylesh et al., 2019). Regarding the conventional morphology status, this study found a lower mean score for abnormal morphology compared with the acceptable maximum limit (30%), which is designated for boar sperm to pass or fail the morphological quality test (Rozeboom, 2000). This score was numerically comparable with the 25.00% score reported in the Czech Republic (Lipenský et al., 2010) but higher than the case (<20%) of South Africa, India, and Benin (Masenya et al., 2011; Chakurkar et al., 2016; Dotché et al., 2021). It is likely that the use of a CASA system, as opposed to the subjective morphology analysis method, and plausibly the effect of the season was partly responsible for such a disparity. Many defects such as sperm size, head shape, head size, and midpiece size may go unnoticed during the subjective assessment, which, as a consequence, results in a lower abnormality score. Additionally, the summer season is associated with an increased incidence of sperm with abnormalities (Lipenský et al., 2010), which probably increased the current score for Lusitu boar sperm. Normal structure is a prerequisite for sperm’s ability to penetrate the ovum layers and successfully fertilize it (Górski et al., 2017). Hence, sperm dimensions and shapes may affect semen fertilizing ability (Kondracki et al., 2012; Chakurkar et al., 2016). Semenologists from the animal divide desire to record all abnormalities on a single sperm cell and calculate specific indices of multiple sperm defects (WHO 2010; Morselli et al., 2019). Multiple abnormalities, sperm deformity, and teratozoospermic indices are of interest because of their correlation with many in vitro and in vivo fertility parameters (Aziz et al., 2004; Morselli et al., 2019). There is no available literature on boar sperm, particularly abnormality indices, that can be used for comparison with the currently observed scores. The only exception was the sperm deformity index in humans (≤ 1.6) and canine sperm (0.45) as well as the teratozoospermic index in canine sperm (1.10). These values compared with those of current findings on Lusitu boar semen suggest a largely normal population of sperm and/or suitability for use (Morselli et al., 2019). Moreover, the difference between Lusitu and Large White in terms of these abnormality indices did not indicate significance. The moderate negative correlation (r = –0.448) between sperm deformity index and vitality, as well as a strong relationship with normal sperm morphology (r = –0.888), was suggestive of the potential of vitality and normal sperm morphology parameters in predicting sperm deformity index. On the other hand, weak correlations with other parameters such as pH, sperm concentration, and acrosome integrity were observed with no significance. The current findings suggest the potential for the use of the sperm deformity index to predict vitality and normal morphology or vice versa. However, causal studies, particularly those focusing on in vivo fertility parameters, are needed to substantiate the findings of this study. It is noteworthy that previous study findings (Morselli et al., 2019) confirmed the potential of the sperm deformity index as a prognostic indicator of in vitro fertilizing potential in canines. The observed total sperm versus concentration, as well as volume, were similar to those of earlier studies (Buranawit and Imboonta, 2016; Dotché et al., 2021). In terms of the relationship between volume and total motility, our results agree with those of a previous study conducted by Dotché et al. (2021). It has been confirmed that not a single characteristic correlated with all the semen attributes evaluated; hence, no single semen trait can be relied on to predict the overall quality of Lusitu boar semen/boar soundness. ConclusionIn conclusion, characterization of Lusitu pigs by their semen characteristics revealed the suitability of Lusitu boar semen for use in AI or breeding purpose. Nevertheless, indigenous Lusitu boars scored higher than the Large White in terms of vitality and pH, while the latter was superior in other semen attributes, including volume, sperm concentration, total sperm, and number of sperm doses. Additionally, not a single semen attribute was correlated with all the other characteristics; hence, multiple semen characteristics should be relied upon to predict Lusitu boar semen quality. The current study was limited to in vitro fertility evaluation; hence, future studies should consider validating the current findings through in vivo fertility evaluation. In addition, establishing the cut-off values of these parameters for use in Lusitu boar ejaculate selection and searching for more efficient boar trainability methods for semen collection are needed. Further, conducting semen preservation studies specific to Lusitu boars will be a crucial step for the widespread dissemination of quality semen doses whenever required within and between farms and long-term preservation of germplasm for future use. AcknowledgmentAll authors would like to acknowledge Prof. King S. Nalubamba, Dr. Benson H. Chisala, Dr. Oswin C. Chibinga, Dr. Vincent Nyau, and Dr. Joyce Mfungwe, the University of Zambia, for their technical and administrative support during this study. The authors thank the UNZABREC team for their special contribution to this work. Special thanks go to JICA for providing laboratory support. The authors also acknowledge the special contribution from RUFORUM, Makerere University, and the University of Zambia in the form of financial support. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no competing interests. FundingThis study received partial funding from RUFORUM, Makerere University, and the University of Zambia. Authors’ contributionsStudy conception, design, sample collection, laboratory work, data analysis, and manuscript writing: RA. Design, supervision, and revision: PCS. Supervision, laboratory work, and manuscript revision: ESM. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data availability All data were provided in the manuscript. ReferencesAbigaba, R., Sianangama, P.C., Nyanga, H.P., Mwenya, W.N.M., and Mwaanga, E.S. 2022a. Traditional farmers’ pig trait preferences and awareness levels toward reproductive biotechnology application in Zambia. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 9(2), 255–266. Abigaba, R., Sianangama, P.C., Nyanga, P.H., Mwenya, W.N.M. and Mwaanga. E.S. 2022b. Attitudes and preferences of traditional farmers toward reproductive biotechnology application for improved indigenous pig production in Zambia. Vet. World. 15(2), 403–413. Althouse, C.G., Levis, G.D. and Diehl, J. 2015. Semen collection, evaluation, and processing in the boar. In Pork industry handbook. Eds., Singleton, W. and Carr, T. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service, p: 6. Aziz, N., Saleh, R.A., Sharma, R.K., Lewis-Jones, I., Esfandiari, N., Thomas, A.J.J. and Agarwal, A. 2004. Novel association between sperm reactive oxygen species production, sperm morphological defects, and the sperm deformity index. Fertil. Steril. 81, 349–354. Bamundaga, G.K., Natumanya, R., Kugonza, D.R. and Owiny, D.O. 2018. Reproductive performance of single and double artificial insemination protocol in Swine. Bull Anim. Health. Prod. Afr. 66, 143–157. BjoÀrndahl, L., SoÀderlund, I., and Kvist, U. 2003. Evaluation of the one-step eosin-nigrosin staining technique for human sperm vitality assessment. Hum. Reprod. 18(4), 813–816. Bonet, S., Briz M. and Yeste M. 2012. A proper assessment of boar sperm function may not only require conventional analyses but also others focused on molecular markers of epididymal maturation. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 47(3), 52–64. Bonet, S., Garcia, E. and Sepúlveda, L. 2013. The boar reproductive system. In: Boar reproduction. Eds., Bonet, S., Casas, I., Holt, W. and Yeste, M. Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, pp: 65–107. . Buranawit, K. and Imboonta, N. 2016. Genetic parameters of semen quality traits and production traits of pure-bred boars in Thailand. Thai. J. Vet. Med. 46(2), 219–226. Chakurkar, B.E., Naik, S.S., Barbuddhe, B.S., Karunakaran, M., Naik, K.P. and Singh, P.N. 2016. Seminal attributes and sperm morphology of Agonda Goan pigs. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 44(1), 130–134. Charneca, R., Vila-Viçosa, M.J. and Nunes, J.L.T. 2007. Evaluation of semen collected from Alentejano Swine boars. Zaragoza, Spain: Paper presented at the International Symposium on the Mediterranean Pig. Comizzoli, P., Mermillod, P. and Mauget, R. 2000. Reproductive biotechnologies for endangered mammalian species. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 40(5), 493–504. Dotché, I.O., Gakou, A., Bankolé, C.B.O.B., Dahouda, M., Houaga, I., Antoine-Moussiaux, N., Dehoux, J.P., Pierre Thilmant, P., Koutinhouin, B.G. and Issaka, Y.A.K. 2021. Semen characteristics of the three genetic types of boars reared in Benin. Asian Pac. J. Reprod. 8(2), 82–89. Frunză, I., Cernescu, H. and Korodi, G. 2008. Physical and chemical parameters of boar sperm. Lucr. ştiinţ. Ser. Med. Vet. 41, 634–640. Gerfen, R.W., White, I.B.R., Cotta, M.A. and Wheeler, M.B. 1994. Comparison of the semen characteristics of Fengiing, Meishan, and Yorkshire boars. Theriogenology 41, 461–469. Górski, K., Kondracki, S. and Wysokińska, A. 2017. Ejaculate traits and sperm morphology depending on Ejaculate volume in Duroc boars. J. Vet. Res. 61, 121–125. Govindasamy, K., Chutia, T., Rahman, M., Kalita, M.K. and Dewry, R. 2021. Economic evaluation of boar semen production unit for smallholder pig production system. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 31(4), 1212–1216. Jaishankar, S., Murugan, M. and Gopi, H. 2018. Semen characteristics of exotic pig breeds. Int. J. Sci. Environ. 7(2), 659–662. Johnson, L., Weitze, F.K., Fiser, P. and Maxwell, M.C.W. 2000. Storage of boar semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 62, 143–172. Kanshi, S., Kumar, R., Singh, M.P. and Sinha, M.P. 2011. Evaluation of boar semen quality. Indian Vet. J. 88(10), 18–19. Karageorgiou, A.M., Tsousis, G., Boscos, M.C., Tzika, D.E., Tassis, D.P. and Tsakmakidis, A.I. 2016. A comparative study of boar semen extenders with different proposed preservation times and their effect on semen quality and fertility. Acta Vet. Brno. 85, 023–031. King, J.G. and Macpherson, W.J. 1973. A comparison of two methods for boar semen collection. J. Anim. Sci. 36(3), 563–565. Knox, R.V. 2016. Artificial insemination in pigs today. Theriogenology 85, 83–93. Kommisrud, E., Paulenz, H., Sehested, E. and Grevle, I.S. 2002. Influence of boar and semen parameters on motility and acrosome integrity in liquid boar semen stored for five days. Acta Vet. Scand. 43, 49–55. Kondracki, S., Iwanina, M., Wysokińska, A. and Huszno, M. 2012. Comparative analysis of Duroc and Pietrain boar sperm morphology. Acta Vet. Brno. 81, 195–199. Kondracki, S., Wysokińska, A., Kania, M. and Górski, K. 2017. Application of two staining methods for sperm morphometric evaluation in domestic pigs. J. Vet. Res. 61, 345–349. Lipenský, J., Lustyková, A. and Čeřovský, J. 2010. Effect of season on boar sperm morphology. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 11(4), 465–468. MACO. 2003. Report on the state of animal genetic resources in Zambia. Mazabuka, Zambia: MACO. Masenya, B.M., Mphaphathi, M.L., Mapeka, M.H., Munyai, P.H., Makhafola, M.B., Ramukhithi, F.V., Malusi, P.P., Umesiobi, D.O. and Nedambale, T.L. 2011. Comparative study on semen characteristics of Kolbroek and Large White boars following computer-aided sperm analysis® (CASA). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10(64), 14223–14229. Morselli, M.G., Colombo, M., Faustini, M. and Luvoni, G.C. 2019. Morphological indices for canine spermatozoa based on the World Health Organization laboratory manual for human semen. Reprod. Dom. Anim. 54, 949–955. Ndofor-Foleng, H.M., Iloghalu, O.G., Onodugo, M.O. and Ezekwe, A.G. 2014. Genetic diversity between Large white and Nigerian indigenous breed of swine using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Agro-Science 13(3), 30–36. Ngcauzele, A. 2018. Seasonal differences in semen characteristics and sperm functionality in Tankwa goats, Masters of Science, Biomedical Science. University of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. Nigatu, Y. 2018. Current status of animal biotechnology and option for improvement of animal reproduction in Asia. Int. J. Livest Prod. 9(10), 260–268. Phiri, J.S., Moonga, E., Mwangase, O. and Chipeta, G. 2013. Adaptation of Zambian agriculture to climate change- a comprehensive review of the utilisation of the agro-ecological regions. Zambia Academy of Sciences. Lusaka, Zambia. Pizzi, F., Gliozzi, T.M., Cerolini, S., Maldjian, A., Zaniboni, L., Parodi, L. and Gandini, G. 2005. Semen quality of Italian local pig breeds. Ital J. Anim. Sci. 4(2), 482–484. Purdy, P.H., Tharp, N., Stewart, T., Spiller, S.F. and Blackburn, H.D. 2010. Implications of the pH and temperature of diluted, cooled boar semen on fresh and frozen-thawed sperm motility characteristics. Theriogenology 74, 1304–1310. Pursel, G.V., Schulman, L.L. and Johnson, A.L. 1973. Effect of holding time on storage of boar spermatozoa at 5°C. J. Anim. Sci. 37(3), 785–789. Ratchamak, R., Vongpralub, T., Boonkum, W. and Chankitisakul, V. 2019. Cryopreservation and quality assessment of boar semen collected from bulk samples. Vet. Med. (Praha). 64(5), 209–216. Roca, J., Parrilla, I., Gil, M.A., Cuello, C., Martinez, E.A. and Rodriguez-Martinez, H. 2016. Non- viable sperm in the ejaculate: Lethal escorts for contemporary viable sperm. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 169, 24–31. Rozeboom, J.K. 2000. Evaluating boar semen quality. In: Extension swine husbandry. Eds., Flowers, W.L. and Singleton, W. . Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina State University: Animal Science Facts. Sancho, S., Pinart, E., Briz, M., Garcia-Gil, N., Badia, E., Bassols, J., Kádár, E., Pruneda, A., Bussalleu, E., Yeste, M., Coll, G.M. and Bonet, S. 2004. Semen quality of postpubertal boars during increasing and decreasing natural photoperiods. Theriogenology 62, 1271–1282. Savić, R., Marcos, A.R., Petrović, M., Radojković, D., Radović, Č. and Gogić, M. 2017. Fertility of boars—what is important to know. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 33(2), 135–149. Savić, R., Petrović, M., Radojković, D., Radović, Č., Parunović, N., Pušić, M. and Radišić, R 2013. Variability of Ejaculate volume and sperm motility depending on the age and intensity of utilization of boars. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 29(4), 641–650. Shylesh, T., Harshan, M.H., Wilson, M., Promod, K., Usha, P.A., Sunanda, C. and Unnikrishnan, P.M. 2019. Fresh semen characteristics of large white Yorkshire boar semen selected for liquid semen preservation. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 8(9), 1584–1590. Sonderman, P.J. and Luebbe J.J. 2008. Semen production and fertility issues related to differences in genetic lines of boars. Theriogenology 70, 1380–1383. Suárez-Mesa, R., Estany, J. and Rondón-Barragán, I. 2021. Semen quality of Colombian Creole as compared to commercial pig breeds. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 53, 129. Van der Horst G. 2017. BrightVit a new microptic vitality stain and module: history, physiological basis, current use and importance. In BrightVit: a new kit for vitality in brightfield assessment. Barcelona, Spain: Microptic, p: 1–6. Van der Horst, G. and Maree, L. 2009. SpermBlue®: a new universal stain for human and animal sperm which is also amenable to automated sperm morphology analysis. Biotech. Histochem. 84, 299–308. WHO. 2010. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen 5th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Abigaba R, Mwaanga ES, Sianangama PC, Nyanga PH, Mwenya WNM. Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 Web Style Abigaba R, Mwaanga ES, Sianangama PC, Nyanga PH, Mwenya WNM. Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=239659 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Abigaba R, Mwaanga ES, Sianangama PC, Nyanga PH, Mwenya WNM. Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Abigaba R, Mwaanga ES, Sianangama PC, Nyanga PH, Mwenya WNM. Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 Harvard Style Abigaba, R., Mwaanga, . E. S., Sianangama, . P. C., Nyanga, . P. H. & Mwenya, . W. N. M. (2025) Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 Turabian Style Abigaba, Rubaijaniza, Edwell S. Mwaanga, Pharaoh Collins Sianangama, Progress H. Nyanga, and Wilson N. M. Mwenya. 2025. Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 Chicago Style Abigaba, Rubaijaniza, Edwell S. Mwaanga, Pharaoh Collins Sianangama, Progress H. Nyanga, and Wilson N. M. Mwenya. "Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Abigaba, Rubaijaniza, Edwell S. Mwaanga, Pharaoh Collins Sianangama, Progress H. Nyanga, and Wilson N. M. Mwenya. "Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2439-2448. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Abigaba, R., Mwaanga, . E. S., Sianangama, . P. C., Nyanga, . P. H. & Mwenya, . W. N. M. (2025) Semen characteristics of indigenous Lusitu boars compared to the Large White pig genotype reared in Zambia. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2439-2448. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.16 |