| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2449-2456 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2449-2456 Research Article Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, IraqRezheen Fatah Abdulrahman1*1Department of Pathology and Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Duhok, Duhok, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. Department of Pathology and Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Duhok, Duhok, Iraq. Email: rezheen.abdulrahman [at] uod.ac Submitted: 27/01/2025 Revised: 25/04/2025 Accepted: 11/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

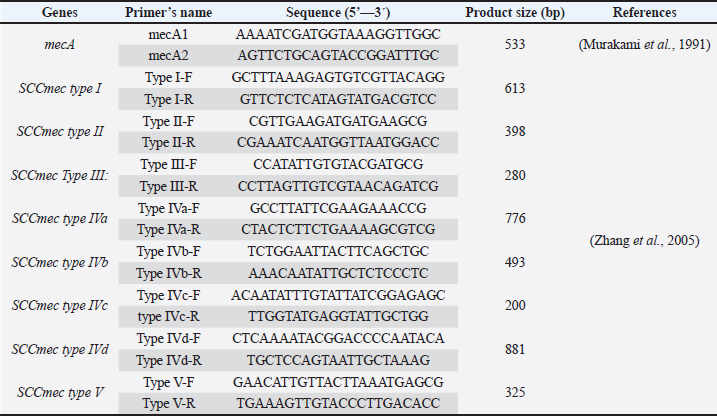

AbstractBackground: Worldwide, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a major nosocomial pathogen responsible for various infections in humans and animals. Aim: This study aimed to determine the prevalence and molecular characteristics of MRSA isolates in healthy pets, specifically cats and dogs. Methods: In this study, swab samples were collected from 135 healthy pets, including 100 cats and 35 dogs. The samples were analyzed using standard microbiology and molecular methods. Results: The results showed the detection of MRSA in nostril isolates at a total rate of 23.2% (13/56) from both cats and dogs through the detection mecA gene. The prevalence rate was different in cats and dogs and it was 22% (9/41) and 27% (4/15), respectively. The same isolates were cefoxitin-positive and oxacillin-resistant. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool analysis of partial mecA sequences revealed 100% similarity with mecA genes from human Staphylococcus aureus isolates. All 13 mecA sequences exhibited identical results. Two partial mecA sequences from this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PQ881807 and PQ881808. The MRSA isolates only displayed staphylococcal cassette chromosome types I and IV (a and b). The results also showed a high prevalence of certain virulence factors, such as hemolysins, across the isolates and multidrug-resistant MRSA isolates among both cats and dogs. Conclusion: This study is the first to confirm the occurrence of MRSA among Duhok pets. The findings suggest the role of healthy animals as reservoirs of multidrug-resistant MRSA and highlight the potential threat of zoonotic transmission of MRSA between pets and humans. Keywords: MRSA, Healthy pets, Nasal carriage, Multi-resistant MRSA, Duhok. IntroductionStaphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a Gram-positive and facultative anaerobic bacterium that commonly colonizes the skin and mucosal surfaces of humans and animals. It is an opportunistic pathogen capable of causing a wide variety of diseases, ranging from superficial skin infections to severe invasive diseases, such as bacteremia, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis (Hanning et al., 2012; Rahimi, et al., 2015). Worldwide, S. aureus has been frequently reported from the nares of farm animals, including cattle, sheep, and goats (Ben Slama et al., 2011; Nemeghaire et al., 2014; Rabaan and Bazzi, 2017; Mourabit et al., 2020; Veen and Abdulrahman, 2023). The emergence of antimicrobial resistance is a significant concern regarding this pathogen, particularly its resistance to the most frequently used antibiotics for treating staphylococcal infections, including β-lactams, which is driven by overuse and misuse (Abdel-Moein and Zaher, 2019; Scott et al., 2022). This resulted in the development of a new strain of this pathogen known as Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains, and resistance occurred through the acquisition of the mecA gene (Katayama, Ito and Hiramatsu, 2000). This gene encodes penicillin-binding protein, and it localizes within the mobile genetic element known as the staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCCmec) (Katayama, Ito and Hiramatsu, 2000). The MRSA strain has been categorized into two main groups: hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA) and community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) strains (Peng et al., 2018). Moreover, livestock-associated MRSA strains have also been categorized (Kinross et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2018; Fetsch, et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Veen and Abdulrahman, 2023). Worldwide, MRSA in animals and in food is a public health concern and a threat because of the possibility of subsequent transmission of MRSA to humans from animals (Weese and van Duijkeren, 2009). The isolation of MRSA strains, including multidrug-resistant strains, from healthy farm animals indicates that farm animals represent a potential reservoir for MRSA with public health threats (Abdel-Moein and Zaher, 2019; Veen and Abdulrahman, 2023). Regarding pet animals, little is known about the prevalence of S. aureus, primarily MRSA, in healthy pets. However, studies have demonstrated the presence of S. aureus in companion animals, indicating their potential role in the dissemination of MRSA within household environments (Khairullah et al., 2023). MRSA is an emerging pathogen causing serious public health threats (Nemeghaire et al., 2014; Abdel-Moein and Zaher, 2019; Pirolo et al., 2019). Previous research revealed the occurrence of MRSA among healthy domestic animals in Duhok city (Veen and Abdulrahman, 2023). However, to the best of my knowledge, no studies have been conducted in Iraq, including Duhok Province, to investigate the prevalence and characterization of S. aureus, particularly MRSA isolates, from the nasal cavity of healthy pets, including cats and dogs. To examine the potential role of healthy household animals as reservoirs of MRSA and assess the risk of zoonotic transmission of MRSA between pets and humans, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of MRSA isolates in healthy pets and to characterize the recovered isolates. Materials and MethodsSample collectionNasal swab samples were collected from the nostrils of 135 apparently healthy pets, including 100 cats and 35 dogs. The samples were collected from household pets in Duhok Province from October 2023 to June 2024. The samples were collected as follows: First, sterile cotton swabs were moistened with normal saline and inserted into the nostrils of healthy cats and dogs very carefully. Once the swab was inserted, it was rotated very gently to contact the skin, as previously mentioned (Loeffler et al., 2011). The swabs were aseptically suspended in 10 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Himedia Laboratories, India). The inoculated broths were transported to the Microbiology Laboratory/ Collage of Veterinary Medicine and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. After 24 hours of incubation, a loopful of broth culture was streaked onto mannitol salt agar (Acumedia, USA) as a selective medium for the isolation and primary identification of S. aureus, and the plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Primary isolation and identification of S. aureusPrimary isolation and identification of S. aureus isolates were performed through phenotypic characterization using standard conventional methods, as mentioned by (Markey et al., 2013). The suspected mannitol fermenter colonies were further subjected to gram staining and biochemical tests including the catalase and coagulase tests. For further analysis, suspected isolates were maintained in 50% glycerol and brain heart infusion broth stocks and stored at –20°C. Molecular detection of S. aureusDNA extraction DNA was extracted from suspected isolates using the boiling method. Briefly, isolates from –20°C stock cultures were plated onto mannitol salt agar, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. A loopful of bacterial colonies was resuspended in 500 μl of deionized doubled distilled water and mixed very well. The mixture was then boiled for 15–20 minutes in a heating block, and the tubes were immediately placed on ice and then centrifuged at 13,000 X for 5 minutes. The supernatant was collected carefully as DNA. A NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) was used to measure the purity and concentration of DNA; samples were stored at –20°C for further analysis (Abdulrahman et al., 2020; Issa et al., 2021; Abdulrahman, 2021; Veen and Abdulrahman, 2023). Detection of S. aureus in pet animals by specific nuc gene The primer pairs nuc-F1 (AGCGATTGAT GGTGATACGG) and nuc-R1 (ATACGCTAAGCCACGTCCAT) were used to confirm the detection of S. aureus isolates from the nasal carriage of pet animals (Abdulrahman, 2020). A total volume of 25 µl was used to perform the PCR reactions, in which each reaction consisted of 12.5 µl of Add Taq Master (ADDBIO Inc, Korea), 1 µl of each primer, 2 µl of DNA, and 8.5 µl of deionized sterile dH2O. The nuc gene was amplified using initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 minutes followed by 35 cycle reactions of denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. Finally, a final extension was performed at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The amplification of the 226-bp product was confirmed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Detection of Methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates in healthy pets The primer pair mecA1 and mecA2 (Table 1) was used to confirm the detection of MRSA isolates among the pet isolates. Amplification of mecA gene (533 bp) was performed in a total reaction of 50 µl including 25 µl of Add Taq Master (ADDBIO Inc, Korea), 1.5 µl of each primer, 4 µl of DNA and 18 µl of deionized sterile dH2O. The parameters of initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 1 minute, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. were used (Murakami et al., 1991). The detection of mecA gene among the pet S. aureus isolates was confirmed using 2% agarose gels. The confirmation was also confirmed phenotypically through cefoxitin screening and oxacillin resistance. Sequencing of mecA geneThe amplified product of mecA-positive isolates (40 μl) were sequenced using the Sanger sequencing technique by Macrogen, Inc. Sequencing Service (Seoul, South Korea). The partial mecA sequences were analyzed using the BioEdit sequence alignment editor version7 (Hall, 1999). The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis was used for GenBank database searching and to determine the similarity of the sequenced mecA gene with reference sequences in the GenBank database. Table 1. Details of oligonucleotide sequences used to amplify mecA gene and SCCmec types of MRSA isolates.

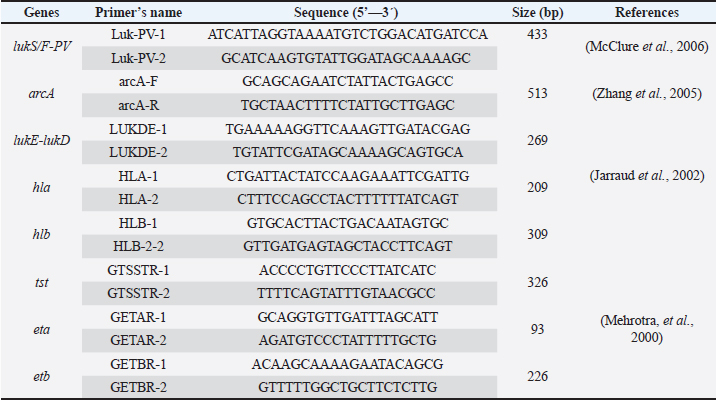

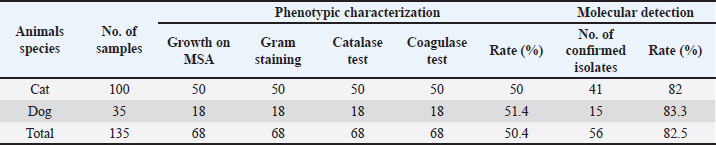

Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec gene typing in MRSA isolates from healthy pet animals Multiplex PCR was used to amplify the SCCmec genes according to the method performed by (Zhang et al., 2005). A PCR mixture volume of 30 µl was used, and the details of the SCCmec primers (I, II, III, IVa, IVb, IVc, IVd, and V) are shown in (Table 1). Characterization of the virulence genes of MRSA isolates from pet animals Different virulence genes were selected to examine whether they were found in MRSA isolates or not. The following virulence genes were selected: Panton-valentine leukocidin (PVL), Arginine Catabolic Mobile Element (arcA), LukE-LukD leucocidin (lukE-lukD) gene, Alpha-hemolysin (hla), Beta-hemolysin (hlb), toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (tst), accessory gene regulator (agr) genes, and exfoliative toxin A (eta) and exfoliative toxin B (etb) genes. A total volume of 20 µl PCR mixture was used, and each gene was amplified according to details described in Table 2. Antimicrobial susceptibility of MRSA isolates The confirmed MRSA isolates by PCR were selected to examine the susceptibly patterns of the 14 antimicrobial agents from different antimicrobial classes using the automated Vitek 2 Compact System. The isolates were categorized as susceptible, resistant, or intermediate according to the guidelines provided. ResultsNasal carriage of S. aureus in healthy pet animalsA total of 135 nasal swabs were collected from apparently healthy household pets, including 100 cats and 35 dogs. Samples were then subjected to phenotypic and molecular characterization. Furthermore, the isolates were screened to obtain an antibiotic resistance profile, and the samples were further processed for the phenotypic detection of MRSA phenotypically and also through the amplification of mecA gene among healthy animals. Of the 135 nasal swabs from both cats and dogs, 68 (50.4%) were tested positive by using standard bacteriological methods. Therefore, the rate was different among the 100 cats: 50 (50%) were positive and among the 35 cats, 18 (51.4%) were suspected. The amplification of the S. aureus species-specific nuc gene (226 bp) showed that of the 68 suspected isolates, 56 (82.4%) samples were confirmed as S. aureus. However, the recovery rate was different; S. aureus was detected in 41 of 50 cats and 15 of 18 dogs at rates of 82% and 83.3%, respectively (Table 3). Nasal carriage of MRSA in healthy petsThe nostrils of healthy pets were also examined to determine whether they carried MRSA isolates or not; the detection was performed through the amplification of mecA gene and phenotypically by antibiotic susceptibility test. The results showed the detection of MRSA in nostril isolates at a total rate of 23.2% (13/56) from both cats and dogs. The prevalence rate was different in cats and dogs and it was 22% (9/41) and 27% (4/15), respectively. Table 2. Details of primers that were used to examine different virulence genes among MRSA isolates.

Table 3. Characterization of S. aureus nasal carriage isolates from healthy cats and dogs using phenotypic and molecular methods.

All 56 isolates were screened phenotypically for the detection of MRSA. The isolates that tested positive for the mecA gene were the only ones that exhibited resistance to both cefoxitin and oxacillin. Overall, 23.2% (13/56) of the samples were cefoxitin screening positive and oxacillin resistant. Nucleotide sequence comparison of partial mecA sequences using BLAST analysis against globally published S. aureus revealed 100% sequence similarity, especially with mecA gene from S. aureus isolates from humans. The 13 mecA sequences were also 100% similar. Two partial sequences (one from each species) of mecA sequenced in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accessions number: (PQ881807 and PQ881808). SCCmec types among MRSA isolatesSCCmec typing using multiplex PCR among 13 pets with MRSA isolates (cat:9; dog: 4) showed variation among the types. The results showed that SCCmec types were found only among 8 of the 13 (61.53%) MRSA isolates from pets. There was also variation among the pets in which 6 of the 9 MRSA isolates from cats and 2 of the 4 MRSA isolates from dogs displayed the presence of SCCmec types. Among the SCCmec types, only SCCmec types I and IV (a and b) were detected, and the other types were not detected. The results of this study showed that only one isolate displayed SCCmec type1 and 7 isolates were SCCmec type IV. The results of this study showed that the most predominant types were SCCmec types IVa and b. Five isolates displayed only one type, including type IVa (n = 4) and type IVb (n:1). However, 3 isolates showed the presence of two types: one isolate displayed the presence of SCCmec type 1 and type IVb; 2 isolates showed the detection of both SCCmec types IVa and IVb. The findings of this study revealed that SCCmec types IVa and IVb were the most predominant SCCmec types. Characterization of virulence genes in MRSA isolates In this study, the presence of several genes was analyzed in order to examine their potential virulence factors. The lukS/F-PV gene, which encodes the PVL toxin, was absent in all samples (0%), suggesting that these isolates do not carry this specific virulence factor, which is commonly linked to more severe infections. The arcA gene, part of the arginine catabolic mobile element, was found only in 15.38% (2/13) of the samples, indicating genetic variability among the isolates. In terms of other virulence factors, the lukE-lukD gene, which encodes leukocidins, was present in the majority of the isolates at a rate of 76.92% (10/13), indicating a widespread potential for immune system evasion. The hla gene, which encodes alpha-hemolysin, was present in 100% of the isolates, whereas the hlb gene, encoding beta-hemolysin, was present in 92.31% (12/13) of isolates. Both of these hemolysins contribute to tissue damage and immune evasion, further enhancing the virulence of these isolates. On the other hand, the tst gene, which encodes toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1), was present in only 30.76% (4/13) of the isolates, this suggests that toxic shock syndrome is not a major concern in this group. The exfoliative toxin genes, eta and etb, were present in 0% and 23.07% (3/13) of the isolates, respectively. These toxins are associated with skin conditions such as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, but their limited presence suggests that these isolates are not predominantly associated with such conditions. Overall, this analysis highlights a high prevalence of certain virulence factors (such as hemolysins) across the isolates, while the presence of toxic shock syndrome and exfoliative toxins is less widespread. These findings provide valuable insights into the pathogenic potential of the MRSA isolated in this study. Analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility among MRSA isolatesThe susceptibility profiles of 14 antimicrobials, including their MIC values and phenotypic resistance patterns, were analyzed and assessed against 13 MRSA isolates in this study. All MRSA isolates tested positive for the cefoxitin screen (100%), indicating the presence of the mecA gene associated with methicillin resistance. Resistance to benzylpenicillin (>0.25 µg/ml) and oxacillin (>2 µg/ml) was also 100% resistant, further confirming their methicillin-resistant phenotype. Vancomycin, linezolid, and rifampicin demonstrated 100% efficacy, with all isolates being 100% susceptible. Gentamicin, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and fusidic acid showed excellent activity against 12 of the 13 isolates (92.31%), with only one isolate (7.69%) resistance. Ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin showed resistance only in two isolates (2/13), at the rate of 15.38%. Inducible resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin was identified in 3 isolates (23.07%), while 8 isolates (61.53%) were fully susceptible, and 2 isolates (15.38%) showed resistance. For tetracycline, resistance was detected in 4 isolates (30.76%), while 10 isolates (69.23%) were susceptible. In this study, multidrug-resistant MRSA isolates among both cat and dog were recognized. It showed that 4 isolate exhibited a multidrug-resistant profile and they were resistant to 5–7 different antibiotics, including benzylpenicillin, oxacillin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and fusidic acid. The results of the susceptibility test showed variation of isolates toward different antimicrobials. Overall, the majority of isolates remained susceptible to linezolid, vancomycin, rifampicin, and trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, providing reliable therapeutic options for treating MRSA infections and they still could be the drug of choice for MRSA infections in pet animals. DiscussionIn this study, the presence of MRSA strains, highlights its dual role as both a commensal and a pathogen in humans and animals. The emergence of MRSA, particularly its resistance to β-lactam antibiotics due to the mecA gene, remains a significant public health concern (Katayama, Ito and Hiramatsu, 2000). In this study, the isolation of MRSA isolates from the nares of healthy pet animals, including dogs and cats, may suggest questions about the potential role of healthy household animals as reservoirs for antimicrobial resistance or act as contaminated vectors. Studies suggested the growing evidence of the zoonotic potential of MRSA and its implications for both animal and human health (Scott et al., 2022). However, it has also been found that the absence of typical risk factors in MRSA isolates from companion animals suggests that they may serve as environmental contaminants rather than representing a direct zoonotic risk (Loeffler et al., 2011). Furthermore, MRSA transmission through pets is still unknown regarding risk factors and the importance of pets as reservoirs of human infections is still poorly understood (Bierowiec, Płoneczka-Janeczko and Rypuła, 2016; Pomba et al., 2017). It has also been stated that MRSA may spread from humans to animals especially people who keep pets at home or work in veterinary hospitals (Khairullah et al., 2023). It has also been support the idea of possible bacterial transmission from animal to human and from animals themselves occurs during live animal marketing (Taha et al., 2024). In this study, the results showed the detection of MRSA from nostril isolates at the total rate of 23.2% (13/56) from both cats and dogs, and the prevalence rate was different in cats and dogs, with 22% (9/41) and 27% (4/15), respectively. The confirmation of MRSA isolates was performed phenotypically and genotypically. Furthermore, phenotypic screening for cefoxitin and oxacillin resistance is also among the most common methods used for identifying MRSA isolates in clinical microbiology (CLSI, 2020). Other previous studies confirmed the detection of MRSA among healthy dogs and cats at low levels (Pomba et al., 2017). A prevalence rate of 0%–4% for MRSA colonization has been detected in healthy cats (Bierowiec, Płoneczka-Janeczko and Rypuła, 2016). In this study, sequencing of mecA revealed 100% identity among the isolates, suggesting a high degree of genetic homogeneity across the isolates. These sequences were 100% identical to the published human MRSA globally, suggesting that the isolated MRSA could be transferred from humans to pet animals. The findings of multiple previous studies have shown that MRSA in people causes MRSA to colonize household animals, including cats and dogs (Khairullah et al., 2023). The sequencing method provides a deeper understanding of genetic diversity and its association with MRSA strains in human infections. Additionally, sequencing has been used to establish genetic links between MRSA isolates from different sources, shedding light on potential transmission pathways. The results of antimicrobial resistance showed that most of the isolates were susceptible to commonly used antibiotics to treat S. aureus infections, and the isolates also exhibited multidrug resistance. MD-MRSA isolates are of particular concern due to their potential to complicate treatment options, contribute to the spread of resistance, and act as a threat to public health (Abdel-Moein and Zaher, 2019). However, the overall susceptibility of most isolates suggests that the emergence of resistance to MRSA in these animals remains relatively limited at this time. However, this finding highlights the need for ongoing surveillance. Household animals in close contact with humans could act as reservoirs for MRSA transmission, particularly if resistance patterns evolve further due to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics in veterinary or human settings (Loeffler et al., 2005). In this study, the identification of SCCmec types IVa and IVb in the isolates was particularly significant. SCCmec type IV is typically associated with CA-MRSA; however, SCCmec types I, II, and III are mostly linked to HA-MRSA (Deurenberg et al., 2007; Deurenberg and Stobberingh, 2009). The detection of SCCmec type IV among the MRSA isolates in healthy pets in this study suggests that these MRSA strains originated from and/or were associated with community-associated reservoirs. Previously, it was shown that SCCmec type IV was detected among healthy animals, highlighting the presence of these genetic elements in both livestock and wildlife (Boost, et al., 2007; Sousa et al., 2020). This suggests the potential for transmission between pets and humans, which can be facilitated by close contact and environments (Leonard and Markey, 2008). Therefore, for better understanding, the relatedness of these animal-associated MRSA strains to those circulating in humans, further genomic studies are required. Interestingly, the virulence profile of the isolates was limited, with only the alpha-hemolysin (hla) gene detected, which was more prevalent. The hla gene encodes an alpha-hemolysin toxin that is responsible for tissue damage and immune evasion in S. aureus infections (Berube and Wardenburg, 2013). The high prevalence of lukE-lukD genes is noteworthy, as these genes are implicated in immune system evasion and have been reported as common virulence factors in MRSA isolates from both human and animal sources (Jarraud et al., 2002). This widespread finding supports the idea that lukE-lukD is involved in the pathogenicity of MRSA in various hosts. The absence of other virulence factors, such as pv and other genes, which are commonly associated with severe infections, suggests that these isolates may have no pathogenic potential. However, colonization by MRSA, even strains with limited virulence, may pose a risk for opportunistic infections, especially in immunocompromised hosts, and can act as reservoirs for MRSA transmission (Khairullah et al., 2023). In conclusion, for the first time in Duhok, the detection of MRSA was confirmed in healthy pets. The detection of MRSA in healthy pet animals, confirmed through phenotypic and genotypic methods, highlights the potential for pets to act as reservoirs of MRSA isolates. Although most isolates demonstrated susceptibility to key antibiotics, the presence of SCCmec type IV and the hla virulence gene underscores the importance of continued surveillance and research. Furthermore, in this study, multidrug-resistant MRSA isolates were recognized in both cats and dogs because they were resistant to 5–7 different antibiotics. The findings of this study highlight the role of healthy animals as reservoirs of multidrug-resistant MRSA, highlighting the potential threat of zoonotic transmission of MRSA between pets and humans. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Duhok Research Center, College of Veterinary Medicine, Duhok, Iraq, and the Veterinary Clinics for their endless support. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. FundingNo funding. Authors’ contributionThe author independently developed the research idea, designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. ReferencesAbdel-Moein, K.A. and Zaher, H.M. 2019. Occurrence of multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among healthy farm animals: a public health concern. Inter. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 7(1), 55–60. Abdulrahman, R.F. 2020. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus from local imported chicken in Duhok province/Kurdistan region of Iraq using conventional and molecular methods. Bas. J. Vet. Res. 19(1), 134–146. Abdulrahman, R.F., Abdullah, M.A., Kareem,K.H., Najeeb, Z.D. and Hameed, H.M. 2020. Histopathological and molecular studies on caseous lymphadenitis in sheep and goats in Duhok City, Iraq. Explor. Anim. Med. Res. 10(2), 134–140. Abdulrahman, R.F. 2021. Virulence potential, antimicrobial susceptibility and phylogenetic analysis of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis Iiolated from caseous lymphadenitis in sheep and goats in Duhok City, Iraq. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 9(6), 919–925. Ben Slama, K., Gharsa, H., Klibi, N., Jouini, A., Lozano, C., Gómez-Sanz, E., Zarazaga, M., Boudabous, A. and Torres, C. 2011. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in healthy humans with different levels of contact with animals in Tunisia: Genetic lineages, methicillin resistance, and virulence factors. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30(4), 499–508. Berube, B.J. and Wardenburg, J.B. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin: nearly a century of intrigue. Toxins 5(6), 1140–1166. Bierowiec, K., Płoneczka-Janeczko, K. and Rypuła, K. 2016. Prevalence and risk factors of colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pet cats kept in the city households. BioMed. Res. Inter. 2016,10. Boost, M., O’Donoghue, M.M. and Siu, K.H.G. 2007. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dogs and their owners. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(7), 731–733. CLSI. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 30th Edition. 30th edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Deurenberg, R.H., Vink, C., Kalenic, S., Friedrich, A.W., Bruggeman, C.A. and Stobberingh, E.E. 2007. The molecular evolution of methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(3), 222–235. Deurenberg, R.H. and Stobberingh, E.E. 2009. The molecular evolution of hospital- and community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Current Mol. Med. 9(2), 100–15. Fetsch, A., Etter, D. and Johler, S. 2021. Livestock- sssociated Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus—current situation and impact from a one health perspective. Current Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 8, 103–113. Hall, T.A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis. Nucl. Acid. 41, 95–98. Hanning, I., Gilmore, D., Pendleton, S., Fleck, S., Clement, A. and Park, S.H. 2012. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from retail chicken carcasses and pet workers in Northwest Arkansas. J. Food Prot. 75(1), 174–178. Issa, N.A., Abdulrahman, R.F., Taha, Z.M., Hussain, M.M., Kareem, K.H., Hamadamin, H.I., Najeeb, Z.D., Ahmed, B.M. and Hameed, H.M. 2021. Prevalence and molecular investigation of caseous lymphadenitis among the slaughtered sheep at Duhok Abattoirs; experimental infection with Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis in rabbits. Iraqi J of Vet. Sci. 35(2), 263–270. Jarraud, S., Mougel, C., Thioulouse, J., Lina, G., Meugnier, H., Forey, F., Nesme, X., Etienne, J. and Vandenesch F. 2002. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus genetic background, virulence factors, agr groups (alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immun. 70(2), 631–641. Katayama, Y., Ito, T. and Hiramatsu, K. 2000. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemo. 44, 1549–1555. Khairullah, A.R., Sudjarwo, S.A., Effend, M.H., Ramandinianto, S.C., Gelolodo, M.A., Widodo, A., Riwu, K.H.P. and Kurniawati, D.A. 2023. Pet animals as reservoirs for spreading methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus to human health. J. Adv. Vet. Ani. Res. 10, 1–13. Kinross, P., Petersen, A., Skov, R., Van Hauwermeiren, E., Pantosti, A., Laurent, F., Voss, A., Kluytmans, J., Struelens, M.J., Heuer, O. and Monnet, D.L. 2017. Livestock-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among human MRSA isolates, European Union/European economic area, countries, 2013. Euro. Surveill. 22(44), 16–00696. Leonard, F.C. and Markey, B.K. 2008. Meticillin- Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Animals: a review. Vet. J. 175, 27–36. Loeffler, A., Boag, A.K., Sung, J., Lindsay, J.A., Guardabassi, L., Dalsgaard, A., Smith, H., Stevens, K.B. and Lloyd, D.H. 2005. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among staff and pets in a small animal referral hospital in the UK. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemo. 56, 692–697. Loeffler, A., Pfeiffer, D.U., Lindsay, J.A., Soares Magalhães, R.J. and Lloyd, D.H. 2011. Prevalence of and risk factors for MRSA carriage in companion animals: a survey of dogs, cats and horses. Epidemiol. Infect. 139, 1019–1028. Markey, B., Leonard, F., Archambault, M., Cullinane, A. and Maguire, D. 2013. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology. 2nd Edition. Dublin, Ireland: Mosby Ltd. McClure, J.A., Conly, J.M., Lau, V., Elsayed, S., Louie, T., Hutchins, W. and Zhang, K. 2006. Novel multiplex PCR assay for detection of the Staphylococcal virulence marker Panton- Valentine leukocidin genes and simultaneous discrimination of methicillin-susceptible from-resistant staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44(3), 1141–1144. Mehrotra, M., Wang, G. and Johnson, W.M. 2000. Multiplex PCR for detection of genes for Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1, and methicillin resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38(3), 1032–1035. Mourabit, N., Arakrak, A., Bakkali, M., Zian, Z., Bakkach, J. and Laglaoui, A. 2020. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in farm animals and breeders in north of Morocco. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 1–6. Murakami, K., Minamide, W., Wada, K., Nakamura, E., Teraoka, H. and Watanabe, S. 1991. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29(10), 2240–2244. Nemeghaire, S., Argudín, M.A., Haesebrouck, F. and Butaye, P. 2014. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage isolates from bovines. BMC Vet. Res. 10, 1–9. Peng, H., Liu, D., Ma, Y. and Gao, W. 2018. Comparison of community- and healthcare-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates at a Chinese tertiary hospital, 2012–2017. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–8. Pirolo, M., Gioffrè, A., Visaggio, D., Gherardi, M., Pavia, G., Samele, P., Ciambrone, L., Di Natale, R., Spatari, G., Casalinuovo, F. and Visca, P. 2019. Prevalence, molecular epidemiology, and antimicrobial resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from swine in southern Italy. BMC Microbiol. 19(1), 1–12. Pomba, C., Rantala, M., Greko, C., Baptiste, K.E., Catry, B., van Duijkeren, E., Mateus, A., Moreno, M.A., Pyörälä, S., Ružauskas, M., Sanders, P., Teale, C., Threlfall, E.J., Kunsagi, Z., Torren-Edo, J, Jukes H. and Törneke, K. 2017. Public health risk of antimicrobial resistance transfer from companion animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72(40, 957–968. Rabaan, A.A. and Bazzi, A.M. 2017. Variation in MRSA identification results from different generations of Xpert MRSA real-time PCR testing kits from nasal swabs. J. Infect Public Heal. 10(6), 799–802. Rahimi, H., Saei, H.D. and Ahmadi, M. 2015. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: Frequency and antibiotic resistance in healthy ruminants. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 8(10), 8–13. Scott, N., Seeraj, C., Satram, B., Sandy, N.M., Seuradge, K., Seerattan, B., Seeram, I., Stewart-Johnson, A. and Adesiyun, A. 2022. Occurrence of methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pets and their owners in rural and urban communities in Trinidad. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 16(9):1458–1465. Sousa, M., Silva, N., Borges, V.P., Gomes, J., Vieira, L., Caniça, M., Torres, C., Igrejas, G. and Poeta, P. 2020. MRSA CC398 recovered from wild boar harboring new SCCmec type IV J3 variant. Sci. Total Environ. 722, 137845. Taha, Z.M., Ahmed, M.S., Jwher, D.M.T., Abdulrahman, R.F. and Rahma, H.Y. 2024. Diversity analysis of livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus nasal strains between animal and humans. Open Vet. J. 14(9), 2256–2260. Veen, R. and Abdulrahman, R.F. 2023. Detection and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nasal carriage isolates from healthy domestic animal in Duhok Province. Egyp. J. Vet. Sci. 54(2), 263–273. Wang, B., Xu, Y., Zhao, H., Wang, X., Rao, L., Guo, Y., Yi, X., Hu, L., Chen, S., Han, L., Zhou, J., Xiang, G., Hu, L., Chen, L. and Yu, F. 2022. Methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus in China: a multicentre longitudinal study and whole-genome sequencing. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 11(1), 532–542. Weese, J.S. and van Duijkeren, E. 2009. Methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in veterinary medicine. Vet. Microbiol. 140(3-4), 418–429. Zhang, K., McClure, J.A., Elsayed, S., Louie, T. and Conly, J,M. 2005. Novel multiplex PCR assay for characterization and concomitant subtyping of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec types I to V in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43(10), 5026–5033. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 Web Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=239939 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 Harvard Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman (2025) Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 Turabian Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. 2025. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 Chicago Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. "Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman. "Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2449-2456. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Rezheen Fatah Abdulrahman (2025) Occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pets in Duhok Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2449-2456. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.17 |