| Short Communication | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3334-3340 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(7): 3334-3340 Short Communication The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate productionKoji Sugimoto1, Junichi Nakamura1, Dawei Deng1 and Eiichi Hirano1,2*1Research Institute, Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd.; 1-1 Kurume Research Center bldg., Fukuoka, Japan 2Medical Affairs Department, Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan *Corresponding Author: Eiichi Hirano. Research Institute, Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd.; 1-1 Kurume Research Center bldg., Fukuoka, Japan; Medical Affairs Department, Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. Email: ehirano [at] placenta-jbp.co.jp Submitted: 07/02/2025 Revised: 02/06/2025 Accepted: 09/06/2025 Published: 31/07/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

ABSTRACTBackground: Indoxyl sulfate (IS) is a dietary metabolite of tryptophan that is produced in the liver. It is a uremic toxin that facilitates the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). We previously observed that equine placental extract (ePE) inhibited IS synthesis in an in vitro inhibition assay using the liver S9 fraction. Aim: This study was designed to investigate the effects of ePE on adenine-induced renal failure in mice at the histological and molecular levels to understand the mechanism of action of ePE. Methods: We assessed this effect through biochemical and histological in vivo analyses using a mouse model of CKD and an adenine diet, which induces renal damage through IS production. Results: ePE significantly suppressed serum, renal, and hepatic IS production in adenine diet–fed mice by inhibiting IS synthesis. Histological and semi-quantitative analyses using the tubulointerstitial injury index revealed that ePE effectively prevented the increase in adenine-induced mesangial-positive cell area. Additionally, ePE administration significantly suppressed adenine-induced renal fibrosis in mice. Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that ePE administration reduced the accumulation of F4/80-positive macrophages in the interstitial inflammatory infiltrates. Conclusion: These results suggest that ePE ameliorates IS-associated renal injury in adenine diet-fed mice by reducing IS production in the interstitium of the kidneys. Keywords: Equine placental extract, Renal failure, Tubulointerstitial injury, Uremic toxin. IntroductionChronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health challenge characterized by an increasing incidence and poor prognosis. It is characterized by definitive functional and structural (sustained, progressive, and irreversible) alterations in the kidneys. Additionally, it is associated with a higher risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, resulting in the exacerbation of extant CKD (National Kidney Foundation, 2002). The global incidence of CKD is increasing, and effective treatment is not available. Therefore, there is a significant clinical focus on advancing therapies for patients with renal disorders. Indoxyl sulfate (IS), a uremic toxin produced in patients with CKD (Vanholder, et al., 2003), is an end-stage product of dietary tryptophan metabolism in the liver. It has been reported to increase with the severity of renal dysfunction in humans (Lin, et al., 2011) and small laboratory animals (Owada, et al., 2008), dogs, and cats (Chen, et al., 2018; Cheng, et al., 2015). Furthermore, increased IS has been found to be associated with prognosis in humans with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Wu, et al., 2011) and with progression in cats with CKD (Chen, et al., 2018). In healthy individuals, IS is immediately excreted in the urine through proximal tubular secretion, whereas in patients with renal dysfunction, IS accumulates in the blood (Niwa, and Ise 1994; Barreto, et al., 2009). Because IS strongly binds to albumin in the blood, its effective removal using conventional haemodialysis is challenging (Niwa, et al., 1988). Therefore, IS accumulation may cause the progression of glomerular sclerosis or renal fibrosis in patients with renal dysfunction. AST-120, a charcoal adsorbent, reduces serum IS concentrations in patients with CKD by adsorbing IS precursors into the gut, thereby inhibiting CKD progression (Gelasco, et al.,and Raymond 2006; Niwa, 2011). However, high-dose AST-120 is required, which poses challenges for patient adherence. Additionally, nonspecific adsorption of concomitant drugs is a clinical issue (Fukuda, et al., 2008). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel strategies to reduce or eliminate the systemic accumulation of IS in patients with renal disease and uremia. A non-invasive rodent model of CKD was developed by feeding mice an adenine diet (Tamura, et al., 2009; Santana, et al., 2013). This model exhibits uremia and is characterized by tubular interstitial fibrosis with progressive renal dysfunction and pathological conditions resembling human nephritis with interstitial lesions (Ataka, et al., 2003; Tamagaki, et al., 2006; Matsui, et al., 2009). Additionally, the level of IS increases in rats with adenine-diet-induced CKD (Cai, et al., 2021). While placental extract has significant biological functions on the liver, such as antioxidant (Togashi, et al., 2002), anti-inflammatory (Laosam, et al., 2021), and anti-apoptotic (Bak, et al., 2018) effects, few studies have assessed its effects on the kidney. In this study, we assessed the effects of equine placental extract (ePE) on adenine-induced kidney failure in mice both biochemically and histologically. Materials and MethodsInhibition of IS production in rat liver S9 fractionThe animal liver S9 fraction was prepared as previously described (Yoshihara and Ohta, 1998). Male Sprague–Dawley rats (7 weeks old) were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). The liver S9 fraction, containing microsomal and cytosolic fractions, was obtained by centrifugation of whole-liver homogenate in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM potassium chloride at 500 rpm for 100 seconds at 4°C. The supernatant used as the S9 fraction was further centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to separate the microsomes from the cytosolic fraction. The total protein in the S9 fraction was quantified using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The reaction mixture comprised 2.5 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing the S9 fraction (1 mg/ml), reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (β-NADPH) (1 mM), adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulfate (20 μM), uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid (1 mM), and indole (50 μM) with or without the test compounds. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 minutes in a water bath maintained at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 125 μl ice-cold methanol, and the mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant of the reaction mixture was used to determine the IS concentration using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a fluorescence detector (excitation, 280 nm; emission, 390 nm) using mobile phases A (0.2% trifluoroacetic acid) and B (acetonitrile containing 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid). Under the typical mobile phase flow rates (phase A and B with a gradient elution program of B) 0% (16.0 minutes) → 8% (22.5 minutes) → 80% (26.0 minutes). The flow rate was 0.6 ml/minute at a column temperature of 30°C. ePE preparationThe ePE was extracted from frozen equine placenta. After the removal of all blood, the equine placenta was washed and homogenized. The tissue homogenate was digested with pepsin, neutralized, and filtered. The filtrate was autoclaved and lyophilized for use as an ePE. Animals and treatmentsAll animal experiments were conducted according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Research Institute of Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd. All protocols were approved by the Committee for Animal Care and Use of Research Institute of Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd. and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. The approval numbers for the animal experiments were JBP-LAB#2021-03-19 and JBP-LAB#2021-05-31A. Before the operative procedures, the mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection containing 0.45 mg/kg of medetomidine (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Tokyo Japan), 6.0 mg/kg of midazolam (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), and 7.5 mg/kg of butorphanol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation). Seven-week-old male ICR mice were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). Following a 6-day acclimatization period with a base diet and water ad libitum, 24 mice were randomly divided into three groups (n=8/group): normal control (control), adenine (0.2% adenine diet), and adenine + ePE (0.2% adenine diet treatment with 500 mg/kg ePE) groups. The experimental protocol is shown in Figure 1A. Body weight and food and water intake were measured weekly for each mouse. Fourteen days after the start of the experiment, mice were euthanized for further analysis. ePE or water (control and model control) was orally administered once daily for 14 days. Quantification of serum indoxyl sulfateThe serum (20 µl) was pipetted into a microtube, and 100 µl of methanol was added. The mixture was vortexed and subsequently shaken at 300 rpm for 20 minutes. Following centrifugation (1,630 × g, 20 minutes at room temperature), the supernatant was lyophilized. The lyophilized samples were dissolved in 50% acetonitrile (20 ml) and subsequently used for HPLC analysis. Histology and immunohistochemistryMice under anesthesia underwent transcardial perfusion fixation with formalin (10%). The kidneys were excised and embedded in paraffin. Kidney sections (3 µm) were fixed in formalin (4%) for subsequent immunohistological analysis. Morphological analysis of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained kidney sections was performed using a light microscope. A minimum of 30 consecutive interstitial fields were randomly selected for analysis. Tubulointerstitial scores were graded as follows: grade 0, no change; grade 1, lesions occupying < 25% of the area; grade 2, lesions occupying 25%–50% of the area; grade 3, lesions occupying 50%–80% of the area; and grade 4, lesions occupying the entire area (> 80%). Tubulointerstitial indices were determined using the mean of all scores (Raij, et al., 1984; Leelahavanichkul, et al., 2010). The renal fibrosis area was observed using Sirius red staining. Following deparaffinization, hydration, and antigen retrieval in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH=6.0), kidney paraffin slices were washed with H2O2 (0.3%) for 30 minutes, followed by blocking in 10% goat serum (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc., USA). Subsequently, cells were incubated for 24 hours with rabbit anti-mouse-F4/80 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Denver, MA, USA) and finally incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labelled anti-rabbit-antibody (Vector, USA) for 60 minutes. 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA) was applied for 7 minutes. All sections were analyzed using ImageJ (version 1.53a) and Photoshop CC 2021® (Adobe).

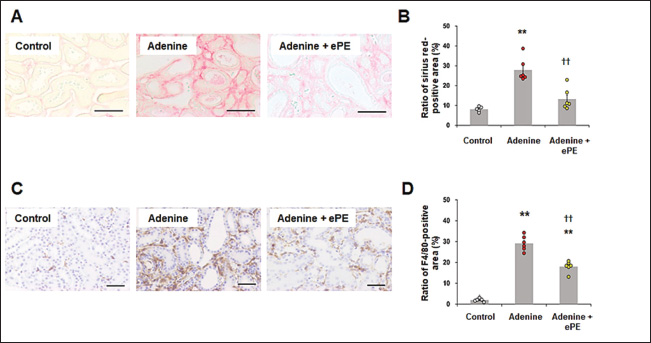

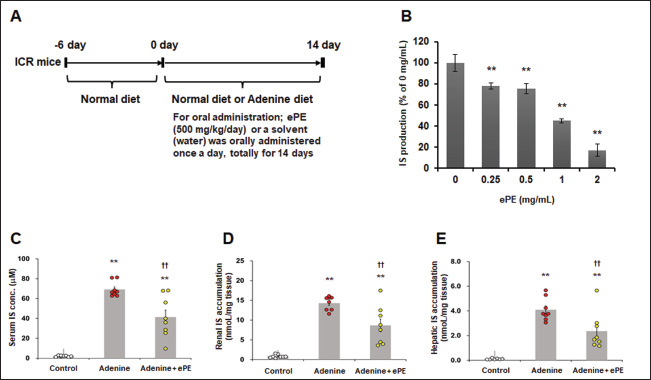

Fig. 1. Inhibitory effects of ePE on IS production in vitro and in vivo. (A) Schematic drawing of experimental protocol. (B) ePE treatment decreased IS production in vitro. IS production inhibitory assay in rat liver S9 fraction. Values are expressed as means ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate, and comparisons between multiple groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Representative data are presented. **p < 0.01 vs. 0 mg/ml. (C) Serum, (D) renal, and (E) hepatic IS concentrations in mice on the adenine diet with or without 500 mg/kg ePE administration. Bars depict means ± SE. One-way ANOVA followed by Scheffe’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons was conducted. n=8. **p < 0.01 vs. Control group, ††p < 0.01 vs. Adenine diet group. Statistical analysisIn vitro data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments, and in vivo data were presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) of two independent experiments. Analyses were conducted using the Bell Curve tool in Microsoft Excel (Social Survey Research Information Co., Tokyo, Japan). Values for the IS synthesis inhibition assay are expressed as the mean ± SD. Multiple group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. In all other tests, the values were expressed as the mean ± SE. Additionally, a one-way ANOVA followed by Scheffe’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons was conducted. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Ethical approvalThis study was conducted according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Research Institute of Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd. All protocols were approved by the Committee for Animal Care and Use of Research Institute of Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd. and the NIH guidelines. The approval numbers for the animal experiments were JBP-LAB#2021-03-19 and JBP-LAB#2021-05-31A. Consent to participate is not applicable. The approval date is 31 May 2021. Results and DiscussionInhibitory effects of ePE on IS production in vitro and in vivoTreatment with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg/ml of ePE significantly inhibited IS synthesis in vitro by 78.3% ± 2.9%, 75.6% ± 4.6%, 45.1% ± 2.1%, and 17.2% ± 5.8%, respectively (Fig. 1A). The serum IS concentration was significantly increased in the adenine group compared with that in the control group (mean IS concentration: control group, 2.1 ± 0.2 mM and adenine group, 69.0 ± 2.5 mM) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, ePE administration significantly suppressed this increase in serum IS levels (mean IS concentration: adenine + ePE group, 41.0 ± 6.9 mM versus adenine group, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). Additionally, an increase in IS concentration in both kidney and liver was significantly induced by 0.2% adenine (mean IS concentration: control group, 0.85 ± 0.14 nM/mg kidney; adenine group, 14.0 ± 0.58 nM/mg kidney and control group, 0.11 ± 0.02 nM/mg liver; adenine group, 4.1 ± 0.31 nM/mg liver). Moreover, this increase in the IS level was significantly reduced by administering ePE (mean IS concentration: adenine + ePE group, 8.7 ± 1.6 nM/mg kidney, 2.4 ± 0.49 nM/mg liver, p < 0.01 versus adenine group) (Fig. 1C and D). Serum IS levels correlate with mortality in patients undergoing dialysis and the incidence of cardiovascular events (Barreto, et al., 2009). IS is produced in the liver by CYP2E1, CYP2A5, and SULT1 (Banoglu, et al., 2001; Banoglu, et al., 2002). Although the gene expression levels of CYP2A5, CYP2E1, and SULT1 were significantly increased by approximately 2.5-fold or more in the kidneys of adenine group mice, ePE administration did not ameliorate the elevation in the expression of these genes (data not shown). The reduction in adenine-induced IS increases in the serum, kidney, and liver following ePE administration was not attributed to alterations in the gene expression of enzymes involved in IS synthesis. This indicates that the mechanism of action of ePE is associated with its enzymatic activity, which involves IS synthesis. Effects of ePE on renal tubulointerstitial injury in mice fed an adenine dietHistological observations of kidney sections revealed hypertrophy of renal tubular epithelial cells and an increase in the extracellular matrix owing to the adenine diet (Fig. 2A). Adenine administration increased the number of mesangial-positive areas in the glomeruli, which were primarily distributed between grades 3 and 4 (Fig. 2B). In grade 3, the mesangial-positive cell area ratio of the adenine diet + ePE group was approximately 2.3 times higher than that of the adenine diet group, whereas in grade 4, the mesangial-positive cell area of the adenine + ePE-administered group was 1/5 of that in the adenine-diet group (mean mesangial-area in glomeruli score: grade 3; control group, 3.0% ± 2.4%; adenine group, 36.0% ± 10.0%; and adenine + ePE group, 84.0% ± 6.0%, and grade 4; control group, 0.0% ± 0.0%; adenine group, 64.0% ± 10.0%; and adenine + ePE group, 12.0% ± 7.0%) (Fig. 2B). Additionally, adenine administration resulted in a significant increase in the tubulointerstitial injury index (TII) score, as observed in the semi-quantitative analysis (mean TII score: control group, 2.2 ± 0.10; adenine group, 4.4 ± 0.12; and adenine + ePE group, 3.7 ± 0.09). However, ePE administration significantly reversed the adenine diet–induced increase in the index score (p < 0.01 versus adenine group) (Fig. 2C).

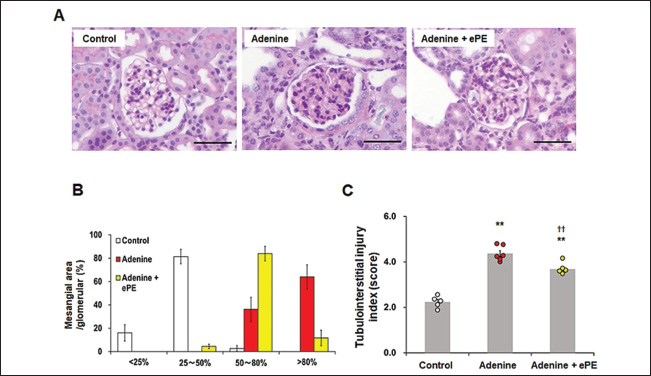

Fig. 2. Tubulointerstitial injury in mice fed a normal or adenine diet with or without ePE. (A) Pathomorphology of renal tissue from mice for tubulointerstitial injury by PAS staining. Scale bars=50 μm. (B) Distribution of mesangial-positive area ratios in glomeruli in each grade as follows: grade 1, lesions occupying < 25% of the area; grade 2, lesions occupying 25%–50% of the area; grade 3, lesions occupying 50%–80% of the area; and grade 4, lesions occupying the entire area (> 80%). (C) Quantification of tubulointerstitial injury index in kidney sections. The tubulointerstitial injury index is presented in the Materials and Methods section. Bars depict means ± SE. n=8. **p < 0.01 vs. Control group, ††p < 0.01 vs. Adenine diet group. IS accumulates in renal tubular cells facilitated by organic anion transporters, such as organic anion transporter 1 and OAT3 (Enomoto, et al., 2002), and induces reactive oxygen species production and antioxidant system disorders. This condition causes tubular cell disorders and facilitates interstitial fibrosis (Taki, et al., 2006). ePE administration significantly suppressed the increase in adenine-induced mesangial-positive cell area. Additionally, it significantly reduced adenine-induced mesangial cell deterioration. Therefore, ePE may reduce tubular interstitial damage by inhibiting mesangial cell activation. These effects may be due to the inhibitory effect of ePE on IS production. Effects of ePE on renal fibrosis and tubulointerstitial inflammation in mice fed an adenine dietSirius red staining revealed that the Sirius red-positive area was significantly increased by approximately 3.5-fold in the adenine-diet group compared with that in the control group (mean Sirius red-positive area: control group, 8.1% ± 0.53% and adenine group, 28.0% ± 2.20%) (Fig. 3A and B). ePE administration significantly reduced the adenine diet-induced Sirius red-positive area (mean Sirius red-positive area: adenine diet + ePE group, 13.0 ± 2.00 %, p < 0.01 % versus adenine group) (Fig. 3B). F4/80-positive macrophage accumulation was significantly increased (approximately 9-fold or more) in the kidneys of adenine group mice (mean F4/80-positive area: control group, 2.0% ± 0.3% and adenine group, 29.0% ± 1.3%) (Fig. 3C and D). In ePE-treated mice, the F4/80-positive area was significantly reduced (mean F4/80-positive area: adenine + ePE group, 18.0% ± 1.0%, p < 0.01 versus 0.2% adenine group) (Fig. 3D). The suppression of renal fibrosis by ePE observed through Sirius red staining, may correlate with the reduction in the mesangial-positive cell area by ePE in PAS staining. Additionally, the antifibrotic effect of placental extract in the liver and heart has been observed in the kidneys (Yamauchi, et al., 2019a; Yamauchi, et al., 2020), indicating that this effect may not be limited to specific organs. Macrophage accumulation in renal tubular cells significantly influences CKD progression. It was significantly reduced by placental extract treatment in an iron-overload mouse model (Yamauchi, et al., 2019b). ePE administration suppresses macrophage accumulation in the renal interstitium. This indicated that ePE inhibited macrophage accumulation in the kidneys. In addition, macrophage accumulation can induce chronic inflammation and organ damage. Placental extracts have direct inhibitory effects on pro-inflammatory mediators in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage cell lines (Chen, et al., 2012). Thus, it is suggested that ePE reduces macrophage accumulation in adenine-fed mice due to its anti-inflammatory effects via the inhibition of IS synthesis.

Fig. 3. Renal fibrosis and macrophage accumulation in mice fed a normal or adenine diet with or without ePE. (A) Pathomorphology of Sirius Red staining of mouse kidney tissue for renal fibrosis evaluation. Scale bars=50 μm. (B) Quantification of the Sirius red-positive area in the kidney sections. The red areas indicate renal interstitial fibrosis. Bars depict means ± SE. n=8. **p < 0.01 vs. Control group, ††p < 0.01 vs. Adenine diet group. (C) Immunostaining of F4/80 in mice. The dark brown areas indicate renal interstitial immune cell infiltration. Scale bars=50 μm. (D) Quantification of the F4/80-positive area in kidney sections. n=8. **p < 0.01 vs. Control group, ††p < 0.01 vs. Adenine diet group. ConclusionOur results showed that ePE ameliorated IS-associated renal injury in mice fed an adenine diet. The effect of ePE on the interstitium in the kidneys of adenine diet-fed mice is mediated by the inhibition of IS production. Further clinical trials to better understand the efficacy, safety, and mode of action of ePE are warranted. In addition, the results of this study are valuable as a first step toward therapeutic application in dogs and cats. AcknowledgmentsWe appreciate Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. Conflict of interestAll authors are employees of Japan Bio Products Co., Ltd. The authors declare no conflict of interest. FundingJapan Bio Products Co., Ltd. funded this study. Authors’ contributionsKS and JN performed the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data. DD performed the experiments; provided reagents and materials. EH conceptualized and designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and authored the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. ReferencesAtaka, K., Maruyama, H., Neichi, T., Miyazaki, J. and Gejyo, F. 2003. Effects of erythropoietin-gene electrotransfer in rats with adenine-induced renal failure. Am. J. Nephrol. 23(5), 315–323. Bak, D.H., Na, J., Choi, M.J., Lee, B.C., Oh, C.T., Kim, J.Y., Han, H.J., Kim, M.J., Kim, T.H. and Kim, B.J. 2018. Anti-apoptotic effects of human placental hydrolysate against hepatocyte toxicity in vivo and in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 42(5), 2569–2583. Banoglu, E., Jha, G.G. and King, R.S. 2001. Hepatic microsomal metabolism of indole to indoxyl, a precursor of indoxyl sulfate. Eur. J. Drug. Metab. Pharmacokinet. 26(4), 235–240. Banoglu, E. and King, R.S. 2002. Sulfation of indoxyl by human and rat aryl (phenol) sulfotransferases to form indoxyl sulfate. Eur. J. Drug. Metab. Pharmacokinet. 27(2), 135–140. Barreto, F.C., Barreto, D.V., Liabeuf, S., Meert. N., Glorieux, G., Temmar, M., Choukroun, G., Vanholder, R., Massy, Z.A. and European Uremic Toxin Work Group (EUTox). 2009. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4(10), 1551–1558. Cai, H., Wang, J., Luo, Y., Wang, F., He, G., Zhou, G. and Peng, X. 2012. Lindera aggregata intervents adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by mediating metabolism and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 134, 111098. Chen, C.P., Tsai, P.S. and Huang, C.J. 2012. Antiinflammation effect of human placental multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells is mediated by prostaglandin E2 via a myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88-dependent pathway. Anesthesiology 117(3), 568–579. Chen, C.N., Chou, C.C., Tsai, P.S.J. and Lee, Y.J. 2018. Plasma indoxyl sulfate concentration predicts progression of chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats. Vet. J. 232, 33–39. Cheng, F.P., Hsieh, M.J., Chou, C.C., Hsu, W.L. and Lee, Y.J. 2015. Detection of indoxyl sulfate levels in dogs and cats suffering from naturally occurring kidney diseases. Vet. J. 205(3), 399–403. Enomoto, A., Takeda, M., Tojo, A., Sekine, T., Cha, S.H., Khamdang, S., Takayama, F., Aoyama, I., Nakamura, S., Endou, H. and Niwa, T. 2002. Role of organic anion transporters in the tubular transport of indoxyl sulfate and the induction of its nephrotoxicity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13(7), 1711–1720. Fukuda, Y., Takazoe, M., Sugita, A., Kosaka, T., Kinjo, F., Otani, Y., Fujii, H., Koganei, K., Makiyama, K., Nakamura, T., Suda, T., Yamamoto, S., Ashida, T., Majima, A., Morita, N., Murakami, K., Oshitani, N., Takahama, K., Tochihara, M., Tsujikawa, T. and Watanabe, M. 2008. Oral spherical adsorptive carbon for the treatment of intractable anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103(7), 1721–1729. Gelasco, A.K. and Raymond, J.R. 2006. Indoxyl sulfate induces complex redox alterations in mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 290(6), F1551–F1558. Laosam, P., Panpipat, W., Yusakul, G., Cheong, L.Z. and Chaijan, M. 2021. Porcine placenta hydrolysate as an alternate functional food ingredient: in vitro antioxidant and antibacterial assessments. PLoS One. 16(10), e0258445. Leelahavanichkul, A., Yan, Q., Hu, X., Eisner, C., Huang, Y., Chen, R., Mizel, D., Zhou, H., Wright, E.C., Kopp, J.B., Schnermann, J., Yuen, P.S. and Star, R.A. 2010. Angiotensin II overcomes strain-dependent resistance of rapid CKD progression in a new remnant kidney mouse model. Kidney Int. 78(11), 1136–1153. Lin, C.J., Chen, H.H., Pan, C.F., Chuang, C.K., Wang, T.J., Sun, F.J. and Wu, C.J. 2011. p-Cresylsulfate and indoxyl sulfate level at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 25(3), 191–197. Matsui, I., Hamano, T., Mikami, S., Fujii, N., Takabatake, Y., Nagasawa, Y., Kawada, N., Ito, T., Rakugi, H., Imai, E. and Isaka, Y. 2009. Fully phosphorylated fetuin-A forms a mineral complex in the serum of rats with adenine-induced renal failure. Kidney Int. 75(9), 915–928. National Kidney Foundation. 2002. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 39 (Suppl 1), S1–S266. Niwa, T., Takeda, N., Tatematsu, A. and Maeda, K. 1998. Accumulation of indoxyl sulfate, an inhibitor of drug-binding, in uremic serum as demonstrated by internal-surface reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Clin. Chem. 34(11), 2264–2267. Niwa, T. and Ise, M. 1994. Indoxyl sulfate, a circulating uremic toxin, stimulates the progression of glomerular sclerosis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 124(1), 96–104. Niwa T. 2011. Role of indoxyl sulfate in the progression of chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease: experimental and clinical effects of oral sorbent AST-120. Ther. Apher. Dial. 15(2), 120–124. Owada, S., Goto, S., Bannai, K., Hayashi, H., Nishijima, F. and Niwa, T. 2008. Indoxyl sulfate reduces superoxide scavenging activity in the kidneys of normal and uremic rats. Am. J. Nephrol. 28(3), 446–454. Raij, L., Azar, S. and Keane, W. 1984. Mesangial immune injury, hypertension, and progressive glomerular damage in Dahl rats. Kidney Int. 26(2), 137–143. Santana, A.C., Degaspari, S., Catanozi, S., Dellê, H., de Sá Lima, L., Silva, C., Blanco, P., Solez, K., Scavone, C. and Noronha, I.L. 2013. Thalidomide suppresses inflammation in adenine-induced CKD with uraemia in mice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 28(5), 1140–1149. Taki, K., Nakamura, S., Miglinas, M., Enomoto, A. and Niwa, T. 2006. Accumulation of indoxyl sulfate in OAT1/3-positive tubular cells in kidneys of patients with chronic renal failure. J. Ren. Nutr. 16(3), 199–203. Tamagaki, K., Yuan, Q., Ohkawa, H., Imazeki, I., Moriguchi, Y., Imai, N., Sasaki, S., Takeda, K. and Fukagawa, M. 2006. Severe hyperparathyroidism with bone abnormalities and metastatic calcification in rats with adenine-induced uraemia. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 21(3), 651–659. Tamura, M., Aizawa, R., Hori, M. and Ozaki, H. 2009. Progressive renal dysfunction and macrophage infiltration in interstitial fibrosis in an adenine-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis mouse model. Histochem. Cell. Biol. 131(4), 483–490. Togashi, S., Takahashi, N., Iwama, M., Watanabe, S., Tamagawa, K. and Fukui, T. 2002. Antioxidative collagen-derived peptides in human-placenta extract. Placenta. 23(6), 497–502. Vanholder, R., De Smet, R., Glorieux, G., Argilés, A., Baurmeister, U., Brunet, P., Clark, W., Cohen, G., De Deyn, P.P., Deppisch, R., Descamps-Latscha, B., Henle, T., Jörres, A., Lemke, H.D., Massy, Z.A., Passlick-Deetjen, J., Rodriguez, M., Stegmayr, B., Stenvinkel, P., Tetta, C., Wanner, C., Zidek, W. and European Uremic Toxin Work Group (EUTox). 2003. Review on uremic toxins: classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 63(5), 1934–1943. Wu, I.W., Hsu, K.H., Lee, C.C., Sun, C.Y., Hsu, H.J., Tsai, C.J., Tzen, C.Y., Wang, Y.C., Lin, C.Y. and Wu, M.S. 2011. p-Cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 26(3), 938–947. Yamauchi, A., Kamiyoshi, A., Sakurai, T., Miyazaki, H., Hirano, E., Lim, H.S., Kaku, T. and Shindo, T. 2019a. Placental extract suppresses cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in an angiotensin II-induced cachexia model in mice. Heliyon 5(10), e02655. Yamauchi, A., Kamiyoshi, A., Sakurai, T., Miyazaki, H., Hirano, E., Lim, H.S., Kaku, T. and Shindo, T. 2019b. Development of a mouse iron overload-induced liver injury model and evaluation of the beneficial effects of placenta extract on iron metabolism. Heliyon 5(5), e01637. Yamauchi, A., Tone, T., Toledo, A., Igarashi, K., Sugimoto, K., Miyai, H., Deng, D., Nakamura, J., Lim, H.S., Kaku, T., Hirano, E. and Shindo, T. 2020. Placental extract ameliorates liver fibrosis in a methionine- and choline-deficient diet-induced mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Biomed. Res. Tokyo. 41(1), 1–12. Yoshihara, S. and Ohta, S. 1998. Involvement of hepatic aldehyde oxidase in conversion of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-2,3-dihydropyridinium (MPDP+) to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-5,6-dihydro-2-pyridone. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 360(1), 93–98. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Sugimoto K, Nakamura J, Deng D, Hirano E. The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 Web Style Sugimoto K, Nakamura J, Deng D, Hirano E. The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=241624 [Access: January 12, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Sugimoto K, Nakamura J, Deng D, Hirano E. The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Sugimoto K, Nakamura J, Deng D, Hirano E. The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 12, 2026]; 15(7): 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 Harvard Style Sugimoto, K., Nakamura, . J., Deng, . D. & Hirano, . E. (2025) The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. Open Vet. J., 15 (7), 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 Turabian Style Sugimoto, Koji, Junichi Nakamura, Dawei Deng, and Eiichi Hirano. 2025. The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 Chicago Style Sugimoto, Koji, Junichi Nakamura, Dawei Deng, and Eiichi Hirano. "The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Sugimoto, Koji, Junichi Nakamura, Dawei Deng, and Eiichi Hirano. "The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production." Open Veterinary Journal 15.7 (2025), 3334-3340. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Sugimoto, K., Nakamura, . J., Deng, . D. & Hirano, . E. (2025) The equine placental extract ameliorates renal damage in mice with adenine-induced chronic kidney disease by inhibiting indoxyl sulfate production. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3334-3340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.45 |