| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2610-2625 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2610-2625 Research Article Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, IndiaNilam Wavhal, Pankaj Dhaka*, Simranpreet Kaur, Jasbir Singh Bedi*Corresponding Author: Pankaj Dhaka. Centre for One Health, College of Veterinary Science, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, India. Email: pankaj.dhaka2 [at] gmail.com Submitted: 15/02/2025 Revised: 03/05/2025 Accepted: 10/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

AbstractBackground: Manure waste disposal is an essential aspect of dairy farm biosecurity and significantly impacts farm productivity, animal health, public health, and environmental sustainability. Improper manure management can contribute to pathogen spread, groundwater contamination, and environmental pollution, necessitating targeted interventions. Aim: This study aimed to explore the perceptions, practices, needs, and challenges faced by dairy farmers in Punjab in relation to manure management and its broader implications. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 275 dairy farmers in Punjab using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire included closed-ended, Likert scale-based, and open-ended questions addressing key aspects of manure management. Data were analyzed to explore associations between demographic factors (gender, age, education, herd size) and manure management practices. Results: The analysis revealed that most respondents (66.9% strongly agreed, 33.1% agreed) recognized manure as an effective fertilizer. However, 43.6% strongly disagreed that dung odor should be considered a source of environmental contamination or health concern, and only 47.3% linked manure to pathogen spread. The opinions on groundwater contamination were divided, with 41.1% agreeing and 43.6% strongly disagreeing. Risk practices identified included 92% of farmers storing dung within residential areas and 50.9% handling dung barehanded. Significant associations were observed between demographics and perceptions/practices, with higher education and larger herd sizes positively influencing adherence to proper manure management practices. The farmers emphasized the need for subsidies and training to improve their manure management practices. Conclusion: The study highlights gaps in manure management practices among dairy farmers and underscores the need for targeted interventions, policy support, and awareness campaigns. Strengthening sustainable manure management through collaboration with farmers, extension agencies, researchers, and policymakers, along with innovative approaches, is essential for enhancing farm biosecurity, safeguarding animal, and public health, and ensuring agricultural sustainability. Keywords: Biogas, Cattle, Dairy, Farm biosecurity, Manure, Pathogens. IntroductionThe dairy industry is fundamental to India’s agricultural sector, and it contributes significantly to rural livelihoods and the national economy. With a milk production of 14 million tons in 2023–2024, Punjab accounts for approximately 5.9% of India’s total milk output (BAHS, 2024). Modern dairy farming is primarily operated under intensive confinement systems where cows are milked one to three times daily. To maintain hygiene standards and minimize the risk of udder infections, routine cleaning of dairy sheds is typically performed at least twice daily, commonly after each milking session. This regular cleaning schedule is essential to ensure a clean environment between milking sessions and to support optimal udder health and milk quality. However, improper or unregulated waste disposal from these operations poses serious threats to animal and public health and the environment (Gržinić et al., 2023). The indiscriminate discharge of dung and wastewater can contaminate the farm environment, clog drainage systems, and pollute nearby rivers and water bodies. Further, the stagnant water created by blocked drains fosters mosquito breeding, elevating the risk of vector-borne diseases and releasing unpleasant odors into the community. Additionally, the decomposition of dung produces gases such as carbon dioxide, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and methane, which contribute to air pollution, odor issues, and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby exacerbating climate-related concerns (Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, 2020). Addressing these challenges necessitates the development and implementation of comprehensive farm waste management systems that integrate multiple strategies, including composting manure solids, employing anaerobic digestion to produce biogas, adopting precision nutrient management, and implementing effective wastewater treatment, to minimize environmental impacts and enhance resource efficiency (Bai et al., 2017; Gyadi et al., 2024). Utilizing livestock manure as a fertilizer is a well-documented practice, valued for its high nutrient and moisture content (Ayamba et al., 2021). This approach can reduce the dependency on chemical fertilizers and decrease the need for irrigation for crop production (Khan et al., 2022). However, when not properly managed, manure can lead to significant environmental degradation, affecting soil, water, and air quality (Erisman et al., 2008). Pathogens in livestock manure, such as Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Yersinia enterocolitica, Escherichia coli, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Giardia lamblia, pose animal and public health risks (Pachepsky et al., 2006). The microorganisms are often shed asymptomatically in the manure of infected animals and may contaminate the environment if manure is inadequately managed (Doyle and Erickson, 2006). The survival rates of pathogens vary based on environmental conditions, with some pathogens persisting for extended periods (Wang et al., 2004). Strategies for pathogen inactivation include prolonged manure storage, composting, vermicompost, and anaerobic digestion (Dong et al., 2022). Effective manure management techniques such as piling and aeration create conditions that facilitate microbial degradation and pathogen reduction (Erickson et al., 2010; Chen and Jiang, 2014). High nutrient concentrations in the environment are linked to the excessive application of fertilizers and manure, intensive livestock farming, and suboptimal agricultural practices (Herrero and Gil, 2008). Effective manure management requires a holistic approach that incorporates both on-farm and off-farm strategies to minimize adverse environmental impacts such as nutrient runoff, soil and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and ecological imbalance. Achieving a balance between the volume of manure generated and the agricultural land available for recycling is particularly challenging in many regions (Bernal, 2017). Although associated with environmental and public health concerns, cow dung remains a resource with many beneficial applications. It harbors beneficial microorganisms capable of decomposing organic waste, making it useful for waste management (Umanu et al., 2013; Gyadi et al., 2025). In rural regions of South Asia, dried cow dung is commonly used as a biofuel for cooking, contributing to the reduction in reliance on non-renewable energy sources (Ananno et al., 2021). The manure fibers are utilized in paper production, and cow dung-based mosquito repellents provide a natural alternative to chemical products (Palanisami et al., 2014; Ananno et al., 2021). Additionally, cow dung enhances soil health by promoting the growth of earthworms such as Eisenia andrei, which aid in soil nitrification and fertility (Ramos et al., 2022). It also exhibits antifungal and antimicrobial properties, protecting against plant pathogens and harmful microorganisms (Basak et al., 2002; Tuthill and Frisvad, 2002; Lehr et al., 2006). Agri-environmental programs are designed to encourage sustainable farming practices by promoting behaviors that yield positive environmental outcomes or discouraging practices that lead to environmental harm (Blackstock et al., 2010; Wissman et al., 2013). Past studies indicate that the adoption of manure management practices is influenced by various factors, including local regulatory frameworks, environmental policies, market dynamics, and the structure of the agricultural industry. Additionally, context-specific issues, such as environmental sustainability and socioeconomic conditions, must be considered (Sunding and Zilberman 2001; Prokopy et al., 2008). Factors such as the production system, farm sizes, and current management practices play crucial roles in determining the environmental performance of dairy farms. For instance, Denmark has successfully implemented regulatory mandates and incentives for organic waste processing, prompting studies on farmers’ perceptions and their willingness to adopt such practices (Case et al., 2017). There is growing interest among farmers and agricultural stakeholders in the utilization of animal dung for its agronomic benefits. However, translating this interest into effective manure management practices demands well-defined guidelines and practical recommendations. Understanding dairy farmers’ needs, practices, and limitations is essential for implementing feasible management technologies. Dairy farmers are key stakeholders in this process; therefore, exploring their insights and identifying barriers to adoption is crucial because their perceptions and practices directly impact the success of manure management strategies. Surveys and studies assessing stakeholder attitudes and needs are crucial for developing tailored interventions and comparing regional and national differences in manure management approaches (Barnes and Toma 2012; Wolf et al., 2016; Hou et al., 2018). With this background, the present study aims to evaluate dairy farmers’ perceptions, practices, needs, and constraints related to manure management in Punjab, while identifying practical strategies for effective dairy waste management. Materials and MethodsStudy design and questionnaire developmentThe present study employed a descriptive cross-sectional survey conducted from May 2023 to May 2024 to capture dairy farmers’ perspectives and gather information on dairy waste management perceptions, practices, needs, and barriers. The questionnaire was developed based on expert consultations with veterinary academicians of Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, India (Supplementary File 1). The questionnaire was designed to assess quantitative and qualitative data on key aspects of dairy manure management. Closed-ended questions provided a structured method for collecting consistent information, Likert-scale items enabled the quantitative assessment of respondents’ perceptions, and open-ended questions allowed for an in-depth qualitative exploration of the themes. The survey covered topics, such as existing knowledge, perceptions, identified needs, and perceived barriers related to farm waste management. The initial 36-item questionnaire underwent evaluation by three expert researchers who applied content validity criteria such as clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness to identify and address any ambiguities. A pilot test involving ten dairy farmers and ten veterinary postgraduate students was conducted to refine the questionnaire length, clarity, and sequence. Based on the feedback received, ambiguous or irrelevant items were removed, yielding a final version with 30 questions. The survey was segmented into sections that addressed demographic information, manure management practices, perceptions, and barriers. Perceptions were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The parameters for “needs” and “barriers” were adapted from previous studies (Bernal, 2017; Case et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2018). An overview of the study design, sample size, and key analytical domains is presented as a flowchart in Figure 1. Sampling procedureThe study targeted dairy farmers as the source population, and the inclusion criteria required participants to own at least two dairy animals, regardless of land ownership. Using the Raosoft sample size calculator (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html?nosurvey), a sample size of 267 was estimated. A 50% response distribution was selected as a conservative baseline to maximize the required sample size in cases in which the true proportion is unknown. A 5% margin of error was employed to ensure a reasonable level of precision, and a 90% confidence level was chosen to balance statistical reliability with resource constraints. The survey was administered through one-on-one interviews and conducted in Punjabi (regional language), Hindi, and English as needed to ensure clarity and comprehension.

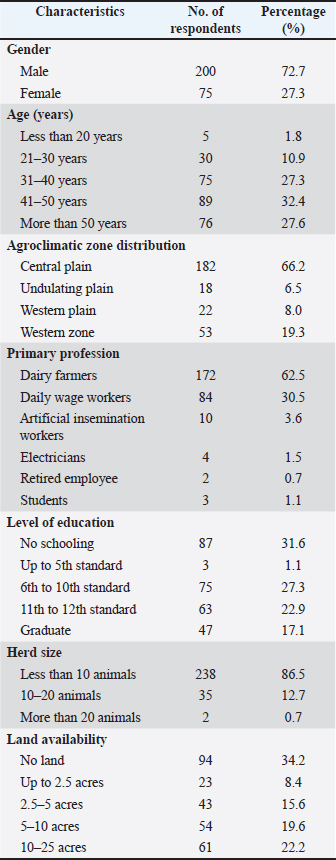

Fig. 1. An overview of the study design, sample size, and key analytical domains of the dairy farm waste perception and practices survey among farmers in Punjab, India. Statistical analysisData collected from the survey were compiled in Microsoft Excel 2010, cleaned for inconsistencies, and further analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including median, frequency, and percentage, were calculated for demographic and required outcome variables. A total of 10 perception and practice parameters were evaluated using an appropriate scoring system, which was provided in consultation with the University experts based on the correct responses (Supplementary File 2). The scores were then categorized into median, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile. The normality assumption for parametric tests was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Pearson correlation was used to explore linear relationships between continuous variables (e.g., age and score, education, and score). The independent samples t-test was employed to evaluate the impact of sex on scores. One-way ANOVA was used to compare mean scores across more than two groups (e.g., education levels, age categories, number of animals). Post hoc comparisons (e.g., Bonferroni correction) were employed to identify specific group differences. For the analysis of multiple-response questions related to needs and barriers, the absolute number of respondents who selected each option was converted to a percentage of the total number of respondents who answered the question. Ethical approvalThe required ethical permission for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab (Ethical approval number: DMCH/ IEC/2024/316). The participation of the farmers in the study was entirely voluntary, with informed consent obtained from all respondents. Participants were informed of the study objectives and were assured that their personal information would remain confidential and be used solely for research. ResultsThe present study obtained 287 (82%) responses out of 350 targeted surveys, with 275 (78.6%) respondents providing complete information. Twelve surveys with incomplete information were eliminated from the study. Demographic analysisThe demographic profile of the participants included the four agroclimatic zones of Punjab (Table 1). Out of 275 participants, the majority of participants were male (72.7%). The highest number of respondents belonged to the 41–50 age group (32.4%). It was observed that 31.6% of respondents had no schooling. The respondents with a herd size of less than 10 animals were 86.5%, and 34.2% did not have agricultural land. About 62.5% of dairy farmers were actively involved in dairy farming, while other participants were maintaining animals as a secondary source of income. Table 1. Demographic details of respondents.

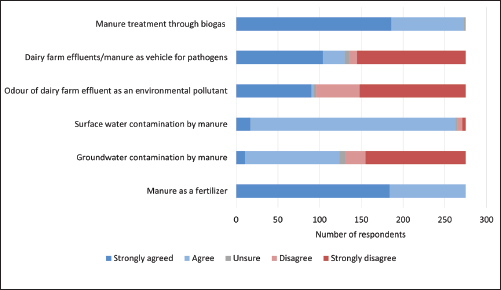

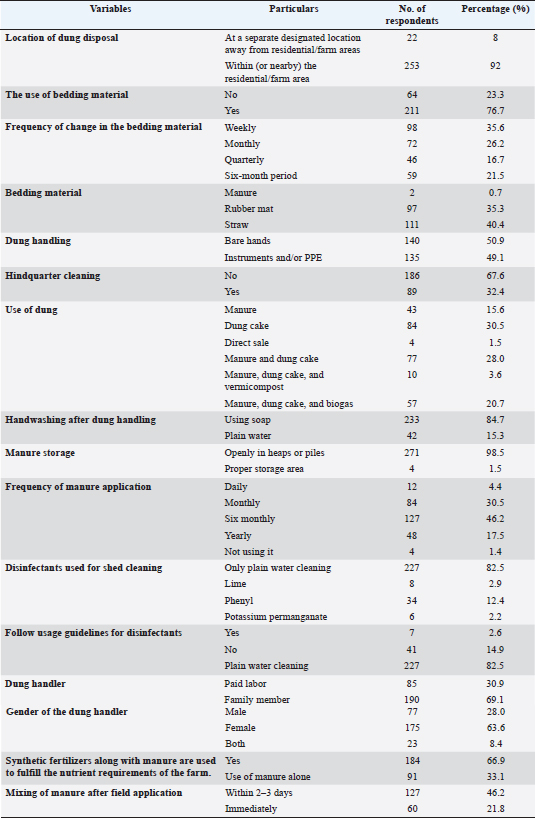

Fig. 2. Stakeholder perceptions of key risks and management aspects of dairy manure handling. Perception about manure managementMost respondents across all regions strongly agreed (n = 184, 66.9%) or agreed (n = 91, 33.1%) that manure is an effective fertilizer. A total of 43.6% (n=120) respondents strongly disagreed that dung odor should be considered a source of environmental or health concern, while 47.3% (n = 130) linked manure to pathogen spread. Interestingly, 41.1% (n = 113) of respondents agree and 43.6% (n = 120) strongly disagree that manure can contaminate groundwater. However, it is widely agreed that dairy farm wastewater might infiltrate surface water sources. The frequency data distribution of the perception-related parameters is presented in Figure 2. The awareness of the potential role of mismanaged dairy farm effluents and manure in pathogen transmission varied significantly across age groups. Among respondents over 50 years of age, only 30.3% (23/76) agreed with related statements, while 69.7% (53/76) disagreed, indicating relatively low awareness in this group. The 41–50 years group was nearly divided, with 48.3% (43/89) agreeing and 51.7% (46/89) disagreeing. In contrast, 74.7% (56/75) of those aged 31–40 years agreed, indicating a higher level of awareness. Notably, the highest awareness was seen among the youngest respondents (<20 and 21–30 years combined), where 85.7% (30/35) agreed and only 14.3% (5/35) disagreed. In addition, education level emerged as a key factor influencing awareness of the public health risks associated with mismanaged dairy effluents and manure. Among respondents without formal schooling, only 3.4% (3/87) recognized the risks, highlighting a significant gap in basic awareness. Awareness gradually improved with increasing education levels. Among those educated up to 5th standard, 33.3% (1/3) agreed with the health risk statements. A more substantial 69.3% (52/75) of individuals with education from 6th to 10th standard demonstrated awareness, increasing further to 90.5% (57/63) among those with 11th to 12th standard education. Among graduates, 95.7% (45/47) agreed, clearly reflecting a positive correlation between higher education and awareness of pathogen transmission risks from dairy farm waste. Practices in dairy waste and manure managementThe analysis of practice-related parameters is presented in Table 2. Only 8% of respondents stored manure at a separate designated location away from residential/ farm areas. A total of 76.7% of respondents used bedding material. A total of 35.6% of respondents changed bedding material at weekly intervals, while 26.2% changed their bedding material at monthly intervals. The majority (40.4%) of respondents used straw as their common bedding material and replaced it weekly. A total of 35.3% of respondents used rubber mats, whereas only 0.7% of respondents used manure as bedding material. About 50.9% of respondents reported handling dung with their bare hands, increasing the risk of exposure to zoonotic pathogens (e.g., E. coli and Salmonella spp.) and other harmful microbes that can lead to infections and disease transmission. Further discussions revealed that many of these farmers were unaware of these potential hazards, highlighting the urgent need to promote safe handling practices and the use of personal protective equipment. All respondents followed cleaning udders before milking, but only 32.4% practiced hindquarter cleaning. Additionally, all respondents who utilized manure as fertilizer on their fields reported having their own transportation arrangements for manure application. Around 82.5% of respondents used plain water for cleaning the farm, and for those who were using any kind of disinfectant, only 2.6% of people admitted following usage guidelines. Most respondents (69.1%) reported that dung was handled by family members, while 30.9% relied on hired labor for dung management. Notably, 63.6% of the dung handlers were female. The majority of respondents (84.7%) were washing their hands with soap; however, 15.3% were washing their hands with plain water. Most respondents (98.5%) admitted that they practiced storing manure in heaps or piles openly without cover. The use of dung varied from manure, dung cake, biogas, vermicompost, and direct sale, but only 20.7% of respondents used biogas as an energy source. The majority of respondents were using manure after six months of storage (46.2%), followed by those who used it monthly (30.5%) and annually (17.5%), while a small percentage utilized it immediately. None of the respondents tested the manure samples for nutrient availability before application in farmland. The quantity of the manure to be applied to farms was measured roughly according to the farmers’ past experiences or community-level opinions. Approximately 66.9% of the farmers admitted to use synthetic fertilizers along with manure as fertilizers. Approximately 46.2% of respondents reported practicing the mixing of manure with soil within 2–3 days, with 21.8% of them doing so immediately after its application in the fields. Table 2. Frequency distribution of dairy waste and manure management practice–related parameters.

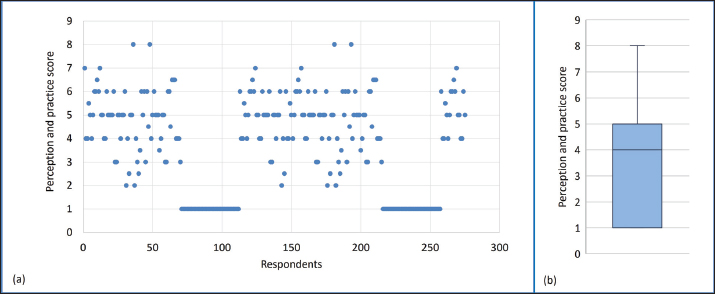

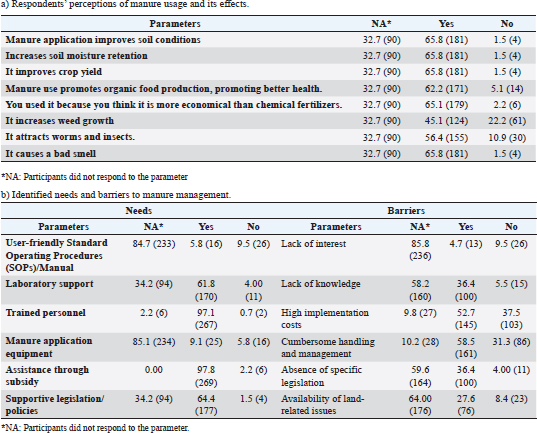

Fig. 3. Distribution of perception and practice scores on manure management: (a) scatter distribution of individual perception and practice scores among respondents (maximum score: 10) and (b) box-and-whisker plot. Perception and practice score analysisThe perceptions and practices of the respondents regarding farm waste management were assessed by scoring 10 parameters (Supplementary file 2). The median value of the score was 4, with an interquartile range of 1–5 (Fig. 3). Association between perception and practice scores and demographic characteristicsA significant positive correlation exists between “education” and “perception and practice score” (r=0.59, p < 0.01). Individuals with higher education levels are likely to achieve higher scores. The “no schooling” group has significantly lower scores than the other education levels. The differences observed were most noticeable between “no schooling” and “6th to 10th standard education” (–4.00), and “no schooling” and “10th to 12th standard education” (–3.59). Small but significant differences exist between “6th to 10th standard education” and “graduate education” (–0.64). A negative correlation (p < 0.05) was observed between “perception and practice score” and “age” (r = –0.38, p < 0.01). This suggests that as individuals get older, their scores tend to decline. The “more than 50 years” group has significantly lower scores compared to the “21–30 years” group (mean difference = –1.80, p < 0.01) and the “31–40 years” group (mean difference=–2.08, p < 0.01). The “41–50 years” group scored significantly lower than the “31–40 years” group (mean difference = –1.26, p < 0.01). On comparing the “herd size” and “perception and practice scores,” a herd size of more than 20 had a higher mean score than a herd size range of 10–20 animals and less than 10 animals (mean difference: 4.56 and 3.0, respectively). An independent samples t-test revealed a significant difference in scores between males (mean score = 3.93, SD = 1.94) and females (mean score = 2.99, SD = 2.22). Needs and barriers to farm waste managementParticipants ranked six needs and barriers parameters for manure management. Table 3a presents respondents’ perceptions of manure usage and its effects, and Table 3b presents survey responses regarding needs and barriers in manure management. Almost all (97.8%) of the participants emphasized the need for subsidies to promote the application of manure as fertilizer. Similarly, 97.1% of respondents agreed that trained personnel are required to ensure proper manure management. A majority of respondents did not provide input on the need for “user-friendly Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)/manuals” (84.7% non-response) or “manure application equipment” (85.1% non-response) (Table 3a). According to 36.4% of respondents, the absence of specific legislation on manure management hinders the adoption of good practices, whereas 64.4% emphasized the need for supportive legislation and policies. The respondents admitted that the main barriers to implementing good manure management practices were lack of knowledge (36.4%), high cost of implementation (52.7%), cumbersome handling and management (58.5%), and land availability (27.6%). The majority of respondents believe that manure improves soil conditions (65.8%), and 65.1% of the farmers admitted that using dung as manure is an economical choice compared to synthetic fertilizers. In addition, 65.8% of farmers showed a positive attitude toward using manure, crop productivity, and the role of manure in improving soil moisture holding capacity. Also, most respondents agreed that manure encourages worm or insect infestation (56.4%) and bad odor (65.8%) after the application of manure on farms (Table 3a). Table 3. Perceptions, needs, and barriers related to manure usage and management. a)Respondents’ perceptions of manure usage and its effects.

DiscussionThe present study provides dairy farmers’ perceptions and practices concerning manure management in Punjab, revealing insights for the formulation of effective waste management strategies. The findings indicate that a participatory approach is essential for comprehending the diverse needs and perceptions of stakeholders and facilitating the design of sustainable manure management practices that account for various socioeconomic and environmental factors. Similar studies have highlighted the effectiveness of such participatory methodologies in enhancing waste management programs by incorporating stakeholders’ perspectives (Blok et al., 2015; Herrero et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2018). There are limited studies in India that highlight the perceptions of farmers considering the public health and environment-related risks of manure or dung along with its benefits for crop improvement (Motavalli et al., 1994; Singh et al., 2020; Dhaka et al., 2023). The experience of rearing animals of the study respondents is reflected in their awareness of manure’s potential environmental impacts, particularly groundwater contamination. Approximately 66.9% of respondents strongly agreed that manure is a valuable fertilizer, yet 41.1% believed that manure could cause groundwater contamination under certain conditions. This concern is supported by previous studies that linked manure and sewage to nitrate pollution in agricultural regions (Ji et al., 2017; Kou et al., 2021). The awareness of groundwater contamination risks appeared higher among farmers from the central plains, potentially influenced by their exposure to discussions at agricultural events such as farmers’ fairs. In contrast, a study in Brazil found that farmers did not consider storage lagoons a contamination risk due to stringent state regulations mandating waterproofed ponds (Palhares, 2008). This discrepancy highlights the influence of regulatory frameworks on farmers’ perceptions. Despite these differences, there is a consensus that improper manure handling can pose significant environmental threats. Herrero et al. (2018) emphasized that the misapplication of manure as fertilizer could lead to soil, water, and air pollution, which is consistent with the concerns raised by the respondents in the present study. Biogas technology was identified as a promising but underutilized manure management strategy, with only 20.7% of respondents adopting it. The barriers to biogas adoption are primarily economic, including high installation costs and complex management requirements. Respondents expressed a strong need for financial support and training, which is consistent with findings from global studies (Roubík et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022). In Brazil, biogas adoption has been incentivized through the National Plan on Climate Change and the National Program for Low-Carbon Agriculture, which provides financial support and promotes sustainable farming practices (Aneel, 2012; Herrero et al., 2018). Similarly, Denmark’s biogas expansion has benefited from a comprehensive incentive strategy, including subsidies for plant construction and initiatives fostering collaboration among different socioeconomic groups (Raven and Gregersen, 2007). The need for similar incentives in Punjab is evident, with 97.8% of respondents advocating for subsidies to promote manure management and biogas use. This aligns with the observations of Singh and Singh (2016), who identified financial constraints as a significant barrier to manure management in India. The management constraints were further emphasized, with cumbersome processes and costly installations cited as major hurdles. In Chile, researchers observed similar limitations, noting the low methane production potential of dairy slurry and the high costs associated with anaerobic digestion plants (Salazar et al., 2007). The present study supports these findings, highlighting the need for affordable and user-friendly biogas and other manure management technologies. The respondents also pointed out that trained personnel and supportive legislation or policies are necessary to enhance manure management practices. Studies by Loyon et al. (2016) and Wissman et al. (2013) have demonstrated that economic incentives and legislative support are crucial for influencing farmers’ decision-making and promoting sustainable waste management practices. Despite these constraints, the findings of the present study reveal a recognition among farmers about manure’s benefits for soil health. Respondents noted that manure improve soil water retention, supporting previous research on the positive effects of manure on soil properties (Van-Camp et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2014). However, many farmers applied manure based on traditional knowledge and experience rather than following scientific guidelines. Some respondents stated that a second application of manure in fields was made only after 1 year to prevent nutrient overload. This practice contrasts with the more frequent application of synthetic fertilizers, which are regularly used to meet crop nutrient requirements. Policymakers and stakeholders must focus on developing technologies and “win-win” strategies to promote the sustainable use of manure on farms. The present study highlighted the need for developing user-friendly SOPs or field manuals to address the challenges encountered by farmers in Punjab. Salazar et al. (2010) emphasized that manure management practices should be personalized to each country’s specific conditions, but common performance indicators, such as nutrient balance and environmental risk assessments, should be established to facilitate cross-country comparisons and policy evaluations. The present study also identified significant demographic factors influencing manure management practices, such as age, education level, land availability, and herd size. Older farmers (>50 years) were less concerned about disease transmission than younger groups, who exhibited greater awareness of public health issues. This relationship may reflect factors such as reduced learning efficiency with age or generational gaps in education or exposure. This generational difference may reflect varying levels of exposure to contemporary environmental and health information (Calculli et al., 2021). Education was another critical factor, with more educated respondents demonstrating better awareness of disease transmission risks and adherence to recommended practices. This supports the findings of Vijay et al. (2021), who reported that higher education levels correlate with improved health awareness. Increased animal numbers provide more resources and opportunities, positively influencing scores. These findings underscore the need for demographic-specific interventions, such as targeted educational programs and tailored support for small and large herd owners. Policymakers must also consider the economic realities faced by farmers and incorporate economic assessments into recommended practices to ensure feasibility and sustainability. The results of the present study suggest a need for targeted interventions to address gaps in perceptions and practices among different demographic groups. For instance, awareness campaigns could be designed to educate younger farmers on odor management while equipping older farmers with knowledge about disease transmission risks. Considering the significant positive correlation observed between educational levels and the perception and practice scores related to manure management, it is essential to emphasize the integration of manure management principles into formal education programs, particularly in rural regions with extensive animal husbandry practices. Incorporating targeted training programs on manure management with practical recommendations can significantly enhance stakeholder awareness and compliance with best practices. Additionally, subsidized access to manure management technologies could effectively address the challenges encountered by small-scale herd owners and landholders. Policymakers should consider developing customized subsidy programs tailored to local needs and practices to enhance adoption rates and ensure long-term sustainability. Although this study provides valuable insights, it is limited by its reliance on self-reported data, which may be subject to bias. Future research should incorporate longitudinal designs to assess the impact of educational interventions and policy changes on dairy farming practices. In addition, exploring the role of cultural and regional factors in shaping perceptions and practices may provide a more accurate understanding. By fostering collaboration and innovation, sustainable manure management practices that protect environmental and public health can be advanced while supporting the agricultural economy. ConclusionThe study findings underscore the importance of enhancing manure management practices among Punjab’s dairy farmers to address environmental sustainability and public health challenges. The results revealed significant gaps in awareness and compliance with biosecurity measures, particularly concerning pathogen transmission and disease risks associated with improper manure handling. Demographic factors such as age, education level, and herd size were identified as key determinants influencing farmers’ perceptions and practices. Strategic interventions, including targeted educational programs, subsidized access to biogas technologies, and financial incentives, are essential to bridge these gaps. Effective implementation of these interventions could be led by a collaborative approach involving government bodies, non-governmental organizations, and private-sector partnerships, ensuring a comprehensive and sustainable impact at the community level. Policymakers should develop region-specific guidelines and promote cost-effective practical solutions to encourage the adoption of sustainable manure management practices. Future research should incorporate longitudinal study designs to assess the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving manure management practices. Such studies would facilitate a deeper understanding of temporal changes in farmer behavior while elucidating the cultural, regional, and socioeconomic determinants that influence compliance and adoption rates. AcknowledgmentThe authors are thankful to Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, for providing the necessary support for this study. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. FundingNone. Authors’ contributionsNW, PD, SK, and JSB conceptualized and designed the study. NW, PD, and SK conducted the field research. Data analysis was performed by NW, PD, SK, and JSB. All authors contributed to the writing, editing, and approval of the final manuscript. Data availabilityThe authors confirm that data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its supplementary materials. ReferencesAnanno, A.A., Masud, M.H., Mahjabeen, M. and Dabnichki, P., 2021. Multi-utilisation of cow dung as biomass. In: Sustainable bioconversion of waste to value added products. Eds., Inamuddin, Khan, A. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation (IEREK Interdisciplinary Series for Sustainable Development), Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp: 215–228. Aneel, 2012. Brazilian electrical energy agency. Resolution 482. Available via http://www2.aneel. gov.br/cedoc/ren2012482.pdf (Accessed 12 October 2024). Ayamba, B.E., Abaidoo, R.C., Opoku, A. and Ewusi- Mensah, N., 2021. Enhancing the fertilizer value of cattle manure using organic resources for soil fertility improvement: a review. J. Bioresour. Manag. 8(3), 9. Bai, Z., Li, X., Lu, J., Wang, X., Velthof, G.L., Chadwick, D., Luo, J., Ledgard, S., Wu, Z., Jin, S. and Oenema, O. 2017. Livestock housing and manure storage need to be improved in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 8212–8214. Barnes, A.P. and Toma, L. 2012. A typology of dairy farmer perceptions towards climate change. Clim. Change 112, 507–522. Basak, A.B., Lee, M.W. and Lee, T.S. 2002. In vitro inhibitory activity of cow urine and dung to Fusarium solani f. sp. cucurbitae. Mycobiology 30(1), 51–54. Basic Animal Husbandry Statistics (BAHS). 2024. Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Government of India, New Delhi, India. Available via https://www.dahd.gov.in:80/sites/default/files/2025-01/ FinalBAHS2024Book14012025.pdf (Accessed 9 January 2025). Bernal, M.P. 2017. Grand challenges in waste management in agroecosystems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 1, 1. Blackstock, K.L., Ingram, J., Burton, R., Brown, K.M. and Slee, B., 2010. Understanding and influencing behaviour change by farmers to improve water quality. Sci. Total Environ. 408(23), 5631–5638. Blok, V., Long, T.B., Gaziulusoy, A.I., Ciliz, N., Lozano, R., Huisingh, D., Csutora, M. and Boks, C. 2015. From best practices to bridges for a more sustainable future: advances and challenges in the transition to global sustainable production and consumption: Introduction to the ERSCP stream of the special volume. J. Clean. Prod. 108, 19–30. Calculli, C., D’Uggento, A.M., Labarile, A. and Ribecco, N. 2021. Evaluating people’s awareness about climate changes and environmental issues: a case study. J. Clean. Prod. 324, 129244. Case, S.D.C., Oelofse, M., Hou, Y., Oenema, O. and Jensen, L.S. 2017. Farmer perceptions and use of organic waste products as fertilisers -A survey study of potential benefits and barriers. Agric. Syst. 151, 84 -95; doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2016.11.012 Chen, Z. and Jiang, X. 2014. Microbiological safety of chicken litter or chicken litter-based organic fertilizers: a review. Agriculture 4(1), 1–29. Dhaka, P., Chantziaras, I., Vijay, D., Singh, M., Bedi, J.S., Caekebeke, N. and Dewulf, J. 2023. Situation analysis and recommendations for the biosecurity status of dairy farms in Punjab, India: a cross- sectional survey. Animals 13(22), 3458. Dong, R., Qiao, W., Guo, J. and Sun, H. 2022. Manure treatment and recycling technologies. In Circ. Econ. Sust. 2, 161–180. Doyle, M.P. and Erickson, M.C., 2006. Reducing the carriage of foodborne pathogens in livestock and poultry. Poultry science 85(6), 960-973. Erisman, J.W., Bleeker, A., Hensen, A. and Vermeulen, A. 2008. Agricultural air quality in Europe and the future perspectives. Atmos. Environ. 42(14), 3209-3217; doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.04.004 Erickson, M., Critzer, F. and Doyle, M. 2010. Composting criteria for animal manure: issue brief on composting of animal manure. An initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts at Georgetown University, The Produce Safety Project, Washington, DC, USA. Available via www.producesafetyproject.org (Accessed 17 May 2024). GrĆinić, G., Piotrowicz-CieŚlak, A., Klimkowicz- Pawlas, A., Górny, R.L., ławniczek-Wałczyk, A., Piechowicz, L., Olkowska, E., Potrykus, M., Tankiewicz, M., Krupka, M. and Siebielec, G. 2023. Intensive poultry farming: a review of the impact on the environment and human health. Sci. Total Env. 858, 160014. Gyadi, T., Bharti, A., Basack, S. and Lucchi, E. 2025. Comparative analysis of cow and chicken manure as activators in windrow composting of vegetable waste. Waste Biomass Valorization, 1–13; doi: 10.1007/s12649-025-02893-1. Gyadi, T., Bharti, A., Basack, S., Kumar, P. and Lucchi, E. 2024. Influential factors in anaerobic digestion of rice-derived food waste and animal manure: a comprehensive review. Bioresour. Technol. 413, 131398. Herrero, M.A. and Gil, S.B. 2008. Consideraciones ambientales de la intensificación en producción animal. Ecología Austral. 18(3), 273–289. Herrero, M.A., Palhares, J.C., Salazar, F.J., Charlón, V., Tieri, M.P. and Pereyra, A.M. 2018. Dairy manure management perceptions and needs in South American countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2, 22. Hou, Y., Velthof, G.L., Case, S.D.C., Oelofse, M., Grignani, C., Balsari, P., Zavattaro, L., Gioelli, F., Bernal, M.P., Fangueiro, D. and Trindade, H. 2018. Stakeholder perceptions of manure treatment technologies in Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 1620–1630. Ji, X., Xie, R., Hao, Y. and Lu, J. 2017. Quantitative identification of nitrate pollution sources and uncertainty analysis based on dual isotope approach in an agricultural watershed. Environ. Pollut. 229, 586–594. Khan, I., Amanullah, Jamal, A., Mihoub, A., Farooq, O., Farhan Saeed, M., Roberto, M., Radicetti, E., Zia, A. and Azam, M. 2022. Partial substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic supplements increased wheat productivity and profitability under limited and assured irrigation regimes. Agriculture, 12(11), 1754. Kou, X., Ding, J., Li, Y., Li, Q., Mao, L., Xu, C., Zheng, Q. and Zhuang, S. 2021. Tracing nitrate sources in the groundwater of an intensive agricultural region. Agric. Water Manag. 250, 106826. Lehr, N.A., Meffert, A., Antelo, L., Sterner, O., Anke, H. and Weber, R.W. 2006. Antiamoebins myrocin B and the basis of antifungal antibiosis in the coprophilous fungus Stilbella erythrocephala (syn. S. fimetaria). FEMS Microbio. Ecol. 55(1), 105–112; doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00007.x Li, Q., Wang, J., Wang, X. and Wang, Y. 2022. The impact of training on beef cattle farmers’ installation of biogas digesters. Energies, 15(9), 3039. Loyon, L., Burton, C.H., Misselbrook, T., Webb, J., Philippe, F.X., Aguilar, M., Doreau, M., Hassouna, M., Veldkamp, T., Dourmad, J.Y. and Bonmati, A. 2016. Best available technology for European livestock farms: Availability, effectiveness and uptake. J. Environ. Manage. 166, 1–11; doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.046 Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. 2020. Guidelines for Environmental Management of Dairy Farms and Gaushalas. Government of India. Available via https://cpcb.nic.in/openpdffile.php?id=TGF0ZXN0RmlsZS8yOTlfMTU5NDY0MjQ4Nl9tZWRpYXBob3RvNTU4MS5wZGY=(Accessed 24 July 2024). Motavalli, P.P., Singh, R.P. and Anders, M.M. 1994. Perception and management of farmyard manure in the semi-arid tropics of India. Agric. Syst. 46(2), 189–204. Pachepsky, Y.A., Sadeghi, A.M., Bradford, S.A., Shelton, D.R., Guber, A.K. and Dao, T. 2006. Transport and fate of manure-borne pathogens: Modeling perspective. Agric. Water Manag. 86(1-2), 81–92; doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2006.06.010 Palanisami, S., Natarajan, E. and Rajamma, R. 2014. Development of eco-friendly herbal mosquito repellent. J. Innov. Biol. 1(3), 132–136. Palhares, J.C.P. 2008. Licenciamento Ambiental na Suinocultura: os Casos Brasileiro e Mundial. Concórdia, SC: Embrapa Suínos e Aves, Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. (Documentos/Embrapa Suínos e Aves, no. 123) p: 52. Prokopy, L.S., Floress, K., Klotthor-Weinkauf, D. and Baumgart-Getz, A. 2008. Determinants of agricultural best management practice adoption: evidence from the literature. J. Soil Water Conserv. 63(5), 300–311; doi:10.2489/ jswc.63.5.300 Ramos, R.F., Santana, N.A., de Andrade, N., Romagna, I.S., Tirloni, B., de Oliveira Silveira, A., Domínguez, J. and Jacques, R.J.S. 2022. Vermicomposting of cow manure: effect of time on earthworm biomass and chemical, physical, and biological properties of vermicompost. Bioresour. Technol. 345, 126572. Raven, R.P. and Gregersen, K.H. 2007. Biogas plants in Denmark: successes and setbacks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 11(1), 116–132; doi: 10.1016/j. rser.2004.12.002 Roubík, H., Mazancová, J. and Banout, J. 2018. Current approach to manure management for small-scale Southeast Asian farmers- using Vietnamese biogas and non-biogas farms as an example. Renewable Energy 115, 362–370. Salazar, F., Dumont, J.C., Chadwick, D., Saldaña, R. and Santana, M. 2007. Caracterización de purines de lecherías en el Sur de Chile. Agri. Técnica 67(2), 155–162; doi: 10.4067/S0365-28072007000200005 Salazar, F., Herrero, M.A., Charlón, V. and La Manna, A. 2010. Slurry management in dairy grazing farms in South American countries. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference of the FAO ESCORENA Network on the Recycling of Agricultural, Municipal and Industrial Residues in Agriculture, Lisboa, Portugal, p 13–15. Singh, D. and Singh, K.B. 2016. Analysis of constraints in adoption of biogas technology. J. Community Mobilization Sustainable Dev. 11(1), 45–47. Singh, J., Singh, B.B., Tiwari, H.K., Josan, H.S., Jaswal, N., Kaur, M., Kostoulas, P., Khatkar, M.S., Aulakh, R.S., Gill, J.P.S. and Dhand, N.K. 2020. Using dairy value chains to identify production constraints and biosecurity risks. Animals 10(12), 2332. Sunding, D. and Zilberman, D. 2001. The agricultural innovation process: research and technology adoption in a changing agricultural sector. Handb. Agric. Econ. 1, 207–261; doi: 10.1016/S1574-0072(01)10007-1 Tuthill, D.E. and Frisvad, J.C. 2002. Eupenicillium bovifimosum, a new species from dry cow manure in Wyoming. Mycologia 94(2), 240–246; doi:10.2307/3761800 Umanu, G., Nwachukwu, S.C.U. and Olasode, O.K. 2013. Effects of cow dung on microbial degradation of motor oil in lagoon water. GJBB 2(4), 542548. Van-Camp, L., Bujarrabal, B., Gentile, A.R., Jones, R.J., Montanarella, L., Olazabal, C. and Selvaradjou, S.K. 2004. Reports of the technical working groups. Established under the thematic strategy for soil protection, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, p 162. Vijay, D., Bedi, J.S., Dhaka, P., Singh, R., Singh, J., Arora, A.K. and Gill, J.P.S. 2021. Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) survey among veterinarians, and risk factors relating to antimicrobial use and treatment failure in dairy herds of India. Antibiotics 10(2), 216; doi: 10.3390/ antibiotics10020216 Wang, L., Mankin, K.R. and Marchin, G.L. 2004. Survival of fecal bacteria in dairy cow manure. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 47(4), 1239–1246; doi:10.13031/2013.16574 Wissman, J., Berg, Å., Ahnström, J., Wikström, J. and Hasund, K.P. 2013. How can the rural development programme’s agri-environmental payments be improved? experiences from other countries. Swed. Board Agric. Rep. edn SBO Agriculture (Jönköping), 21. Wolf, C.A., Tonsor, G.T., McKendree, M.G.S., Thomson, D.U. and Swanson, J.C. 2016. Public and farmer perceptions of dairy cattle welfare in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 99(7), 5892–5903; doi:10.3168/jds.2015-10619 Zhang, J.B., Yang, J.S., Yao, R.J., Yu, S.P., Li, F.R. and Hou, X.J. 2014. The effects of farmyard manure and mulch on soil physical properties in a reclaimed coastal tidal flat salt-affected soil. J. Integr. Agric. 13(8), 1782–1790; doi: 10.1016/ S2095-3119(13)60530-4 Supplementary File 1Survey on perceptions and practices of livestock waste management among dairy farmers in Punjab, India Declaration: The survey aims to assess the existing livestock waste management practices, perceptions, needs, and barriers. Participation in the survey is fully voluntary; the identities of study participants will be kept highly confidential and the information from the study will be used for research purposes only. Introductory questionsName: Gender: Male/Female Tehsil:............ Farmland area:............ Age: a) Less than 20 years b) 21-30 years c) 31-40 years d) 41-50 years e) More than 50 years Primary profession: a) Dairy farmer b) Daily wage worker c) Professional advisor d) Others __________ Education qualification: a) No schooling b) Up to 5th c) 6th-10th d) 11th-12th e) Graduate Number of animals at farm: a) Cattle:__________ b) Buffalo:__________ What role does your dairy farm play in your household income? a) Primary income b) Secondary income Survey questions1. What is the location of dung disposal for your dairy farm? a) Within (or nearby) the residential/farm area b) At a separate, designated location away from the residential/farm area 2. Do you use bedding material for animals? a) Yes b) No If yes, please specify the type: Sand/Straw/Grass/Rubber mat/Manure/Other__________ 3. How often do you change the bedding material? a) Weekly b) Monthly c) Quarterly d) 6 months period e) Other__________ 4. Do you use disinfectants for sheds? a) No, I am just cleaning my shed with water a) Yes, within a week interval (name of the disinfectant__________) c) Yes, more than a week gap but not more than a month (name of the disinfectant__________) d) Yes, but after a gap of more than 1 month (name of the disinfectant__________) 5. If you use the disinfectant, do you follow the usage guidelines for disinfectants? Yes No 6. Do you clean the hindquarters of animals before milking every day? Yes No If yes, a) with water only b) by using appropriate sanitizers 7. Do you clean the udder of animals before milking every day? Yes No If yes, a) with water only b) by using appropriate sanitizers 8. Who primarily handles manure? a) Family member b) Paid labor Gender of the manure handler: a) Male b) Female c) Both male and female 9. How many times did you lift the dung and take it out of the animal shed per day? a) Once in a day b) Two times in a day c) Three times in a day d) More than this, as required 10. Do you handle dung with bare hands? a) Yes b) No If no, what do you use__________ 11. Do you wash your hands after doing the dung cleaning? a) Yes b) No If yes, a) with plain water only b) with water and soap c) using hand sanitizer 12. Do you leave manure uncovered in a heap as a common storage method: a) Yes b) No 13. Where do you discard the dung? a) Openly in nearby field areas b) I have proper storage area 14. How do you use dung? a) as manure b) as dung cake c) as plastering material d) for the biogas plant e) other__________ 15. How frequently do you use heaped dung for farm applications? a) Not using it b) Daily usage c) Monthly usage d) Quarterly usage e) Half-yearly usage f) Yearly usage 16. Do you calculate the quantity of manure before application in the farms? a) Yes b) No c) Not applicable 17. Do you use synthetic fertilizers along with manure? a) Yes b) No, we use manure only 18. Do you mix or plow the soil after application of the manure on the fields? a) Yes b) No If yes, a) Immediately after application b) Within 2-3 days c) No fixed schedule, we do as per our convenience 19. Do you carry out chemical analysis of dung for nutrient availability before application in farms? a) Yes b) No 20. Do you agree that groundwater can be contaminated by effluent from dairy farms? a) Strongly agree b) Agree c) Unsure d) Disagree e) Strongly disagree 21. Do you agree that surface water (e.g., water canals) can be contaminated by effluent from dairy farms? a) Strongly agree b) Agree c) Unsure d) Disagree e) Strongly disagree 22. Do you agree that the odor of dairy farm effluent is an environmental pollutant? a) Strongly agree b) Agree c) Unsure d) Disagree e) Strongly disagree 23. Do you agree that dairy farm effluents/manure can be vehicles for the transmission of pathogens? a) Strongly agree b) Agree c) Unsure d) Disagree e) Strongly disagree 24. Do you consider manure as a good fertilizer? a) Strongly agree b) Agree c) Unsure d) Disagree e) Strongly disagree 25. Do you agree that manure treatment through biogas is the best option? a) Strongly agree b) Agree c) Unsure d) Disagree e) Strongly disagree 26. Do you agree with the following statements regarding the application of manure on farms? (Please mark Yes or No for each statement.)

27. Do you agree that limited livestock numbers or insufficient availability of manure leads you to use synthetic fertilizers? a) Yes b) No c) Not applicable 28. Which mode of transport do you use for moving manure from the farm to the field? 29. Have you received any external support to facilitate your dung management practices? a) Yes b) No If yes, from which agency/organization 30. Please indicate the key needs and barriers you perceive in effective manure management. (You may select multipl options from each column.)

Supplementary File 2Scoring of the variables.

| ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Wavhal N, Dhaka P, Kaur S, Bedi JS. Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 Web Style Wavhal N, Dhaka P, Kaur S, Bedi JS. Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=242911 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Wavhal N, Dhaka P, Kaur S, Bedi JS. Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Wavhal N, Dhaka P, Kaur S, Bedi JS. Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 Harvard Style Wavhal, N., Dhaka, . P., Kaur, . S. & Bedi, . J. S. (2025) Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 Turabian Style Wavhal, Nilam, Pankaj Dhaka, Simranpreet Kaur, and Jasbir Singh Bedi. 2025. Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 Chicago Style Wavhal, Nilam, Pankaj Dhaka, Simranpreet Kaur, and Jasbir Singh Bedi. "Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Wavhal, Nilam, Pankaj Dhaka, Simranpreet Kaur, and Jasbir Singh Bedi. "Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2610-2625. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Wavhal, N., Dhaka, . P., Kaur, . S. & Bedi, . J. S. (2025) Manure waste management: Perceptions and practices of dairy farmers in Punjab, India. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2610-2625. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.32 |