| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2626-2650 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2626-2650 Research Article Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in BeninAyaovi Bruno Yaovi1, Nestor Noudeke1, Junior Gbaguidi1, Jean-Eudes Setondji1, Mahugnon Bonaventure Azon1, Gilles A. Toni1, Rodrigue Mêmavo Wankanrin1, Morel Tcheho1, Paulin Azokpota2, Lamine Baba-Moussa3, Souaïbou Farougou1, Philippe Sessou1*1Research Unit on Communicable Diseases, Polytechnic School of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Abomey-Calavi, Benin 2Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, University of Abomey-Calavi, Jericho-Cotonou, Benin 3Laboratory of Biochemistry and Molecular Typing in Microbiology, Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Abomey-Calavi, Abomey-Calavi, Benin * Correspondence to: Philippe Sessou. Research Unit on Communicable Diseases, Polytechnic School of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Abomey-Calavi, Benin. Email: sessouphilippe [at] yahoo.fr Submitted: 16/02/2025 Revised: 26/04/2025 Accepted: 16/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

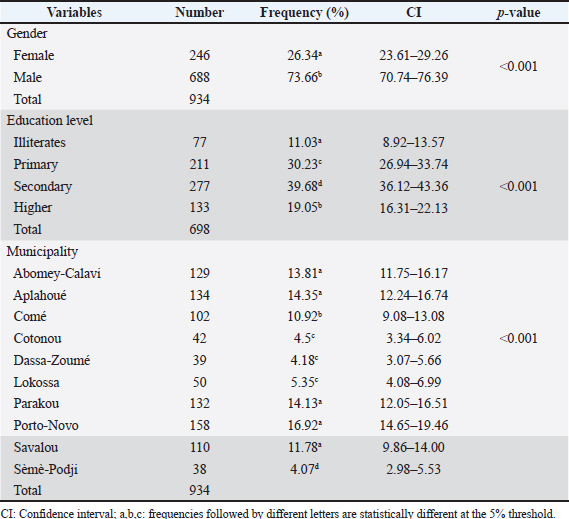

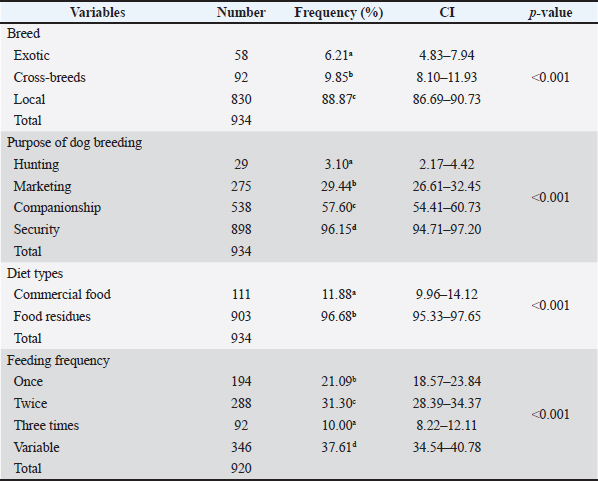

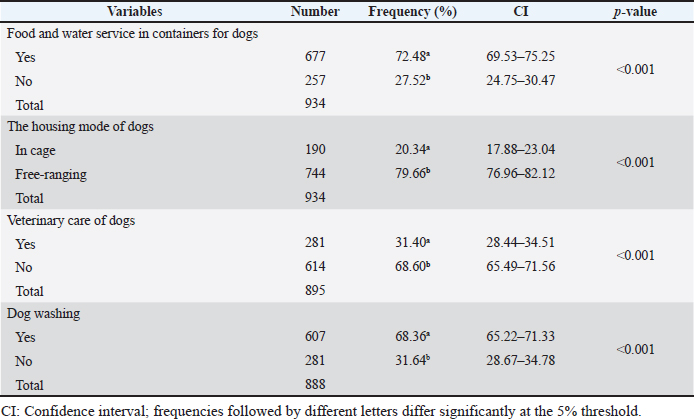

AbstractBackground: Close and frequent contact with dogs that can carry zoonotic agents poses a threat to those interacting with them if necessary precautions are not observed. Aim: This study aimed to describe dog management and hygiene practices among Benin dog owners. Methods: A survey of 934 owners was conducted through direct interviews, and statistical analysis using the multiple correspondence analysis method was carried out on collected data to categorize the groups of dog owners. Results: This study showed that local dogs were more highly bred (88.87%) than cross-breeds (9.85%) and exotic breeds (6.21%). Dogs were more bred for household security (96.15%) than for companionship (57.6%), marketing (29.44%), and hunting (3.10%). The frequency of meals served to the dogs per day varied significantly and consisted mainly of residue food (96.68%). Only 20.34% of owners housed their dogs in cages, and 31.40% hired veterinarians to monitor their dogs. Regarding hygiene practices, 73.95% of owners washed their hands after touching their dogs. Dog excrement was well managed by 27.35% of respondents. The respondents’ education level and municipality had a significant effect on hand hygiene practices, good management of dog excrement, and knowledge of exchanging microorganisms’ risks. Conclusion: This study reveals that all dog owners do not know or observe good hygiene practices. Programs to raise awareness and train dog owners in good hygiene practices need to be developed and implemented to prevent zoonotic diseases in households. Keywords: Attitude, Benin, Dog owners, Hygiene, Knowledge, Zoonosis. IntroductionPet ownership has become a common household practice. These include dogs, cats, rabbits, birds, horses, rats, guinea pigs, fish, snakes, and amphibians (Gwenzi et al., 2021). Of these, dogs are most valued and considered for their ability to provide household security, companionship, hunting, assistance to a person with a physical, mental, sensory disability, and so on (Gates et al., 2019; Gwenzi et al., 2021). A link between dog ownership and self-esteem improvement has also been demonstrated (Schulz et al., 2020). In Nigeria, over 80% of dog owners have close physical contact of less than 50 cm with their dogs, especially during playtime (Daodu et al., 2017). However, close contact between animals and humans offers good conditions for the transmission of microorganisms, either through direct contact (petting, licking, biting, scratching, and so on) or through the domestic environment (contamination of food, furniture, and so on) (Bhat, 2021). Dogs are recognized as potential sources of several zoonotic bacteria that can be transmitted to humans, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Acinetobacter baumannii, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and so on (Costa et al., 2022; Hamame et al., 2022). Additionally, resistance of many of these bacteria to standard antibiotics, such as ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, penicillin, streptomycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol, has been reported (Yaovi et al., 2022). On the other hand, numerous studies have revealed the similarity between multiresistant bacterial strains isolated from dogs and those isolated from their owners (Carroll et al., 2021). However, the direct consequences of infection with antibiotic-resistant microorganisms can be severe: longer duration of illness, increased mortality, prolonged hospitalization, weakened protection during surgery or other medical procedures, and increased costs (OMS, 2016). The indirect effects of resistance are economic losses linked to lower productivity caused by disease and higher treatment costs (OMS, 2016). Given the current extent of antibiotic resistance in the world today, precautions must be taken to prevent the emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant zoonotic agents. One of the precautions to prevent the exchange of microorganisms between dogs and their owners is the observance of good hygiene practices. However, many dog owners are unaware of the good hygiene practices to be observed to avoid reciprocal contamination (Chowdhury et al., 2020). In Benin, very few studies have investigated the hygiene practices of dog owners when caring for their dogs. This lack of information is an obstacle to the fight against zoonotic diseases linked to the exchange of pathogens in households with dogs, especially antibiotic-resistant pathogens. To fill this gap and provide the necessary data to combat zoonotic infections in households with dogs, the present study was initiated and conducted among dog owners in different municipalities of Benin. Material and MethodsQuestionnaireA questionnaire was designed and implemented on the Kobocollect platform and shared with Android smartphones. The questionnaire included questions relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, dog breeding methods, dog disease management, hygiene practices of dog owners, and the attitudes and knowledge of dog owners regarding zoonosis risk. SamplingThe sampling method used in this study was cluster random sampling. The number of dog owners surveyed was determined based on the assumption that at least 50% of the dog owners did not practice good hygiene practices. This number was calculated using Schwartz’s formula (Schwartz, 1995), with a confidence interval of 95% and an absolute precision of 0.05. N = 1,962 * size, Pexp = expected proportion of dog owners who do not observe good hygiene practices when breeding their dogs, and d = desired absolute precision (0.05). Data collectionData collection took place through direct interviews with individuals who owned at least one dog and resided in one of Benin’s municipalities. Ten municipalities were selected based on the significance of dog ownership in the lives of the residents in these areas. These municipalities included Porto-Novo, Aplahoué, Parakou, Abomey-Calavi, Savalou, Comé, Lokossa, Cotonou, Dassa-Zoumè, and Sèmè-Podji. In each municipality, the identified dog owners were informed about the goals of the survey project. Informed consent was obtained from the participants in the study. During the survey, participants were asked to provide voluntarily accurate answers to each question. Consequently, questions that participants did not answer were considered missing data. Statistical AnalysisOnce the survey was completed, the database was downloaded, processed, and coded for statistical analysis using the R version 4.3.3. First, the frequency of each variable’s modalities was calculated. Second, the frequencies of the modalities of each variable were compared using the χ2 test, with a threshold of statistical significance set at 0.05. Third, to categorize the groups of dog owners, a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was conducted using RStudio, a graphical interface for R, along with the packages FactoMineR, Factoshiny, factoextra, and missMDA. MCA enables visualization of similarities between individuals and between the modalities of qualitative variables (Barnier et al., 2024). Variables such as municipalities, gender, dog breeds, purpose of dog breeding, diet types, feeding frequency, food and water service in containers for dogs, housing mode of dogs, veterinary care of dogs, dog washing, dog access to the owner’s lounge, dog access to the owner’s bed, opportunities for contact with dogs, regular touching of dogs, handwashing after touching dogs, good management of dog excrement, home disinfection, the owner frequently licked or scratched by dogs, and dog owners’ knowledge of zoonosis risks were considered. A hierarchical ascending classification of the MCA components was then performed using the hierarchical clustering on principal components function (Barnier et al., 2024). Dog owner groups were identified and characterized by testing each group’s effect using the χ2 test on the variables. Frequencies were compared pairwise between groups using the proportions test with the prop.test function (Barnier et al., 2024). To handle missing data for the selected variable modalities, the method “Imputation by a 2-dimensional MCA model (good compromise)” was used. Fourth, binary logistic regression analyses were used to assess the effect of respondents’ sex, education level, and municipality on handwashing after touching dogs, good management of dog excrement, and knowledge of zoonosis risks between dogs and those around them. For these analyses, glm (generalized linear models) function was used to calculate a wide variety of statistical models. The odds.ratio function of questionr extension was used to determine odds ratios, their confidence intervals, and p-values (Barnier et al., 2024). The significance of the odds ratio was assessed, and the threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05. The quality of the model was then tested by calculating a confusion matrix using the predict method. The overall effect of each variable on the model was tested by performing an analysis of variance using the ANOVA function in the Car package. The best model was selected using a stepwise top-down selection technic based on minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion using the function step (Barnier et al., 2024). Ethical approvalNot needed for this study. ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the survey respondentsTable 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the dog owners surveyed in this study. A total of 934 dog owners participated in the survey, of which 73.66% identified as male and 26.34% as female. Participants with a secondary education level were significantly more represented than those with a primary education level or higher education. Illiterates accounted for 11.03% of respondents. The participants were distributed across Porto-Novo, Aplahoué, Parakou, Abomey-Calavi, Savalou, Comé, Lokossa, Cotonou, Dassa-Zoumè, and Sèmè-Podji municipalities. Dog Breeding PracticesThe analysis in Table 2 indicates that the breeding of local dogs was significantly more common than that of crossbreeds and exotic breeds. The frequency of owners breeding dogs for household security was notably higher than that of owners who owned dogs for companionship, marketing, or hunting. Conversely, owners giving residual food to dogs were more frequent than those serving commercial food to their dogs. Those who fed their dogs at varying frequencies were significantly more important than those who fed their dogs twice, once, and three times. Nearly three-quarters of owners served food in containers specifically for their dogs. Less than a quarter of respondents housed their dogs in cages, and less than a third had hired veterinarians to monitor their dogs. More than half of the respondents frequently washed their dogs. Dog disease managementTable 3 shows that in the event of dog diseases, the frequency of dog owners calling a veterinarian was significantly higher than that of owners who did nothing or resorted to traditional treatments for their dogs. Out of 805 respondents, 32.42% took their dogs to a veterinary practice for checkups. Nevertheless, 13.84% of respondents reported having antibiotics at home to treat their dogs in case of diseases. Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

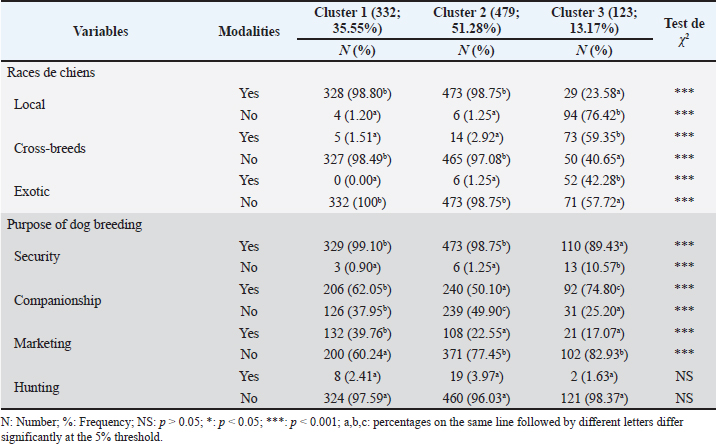

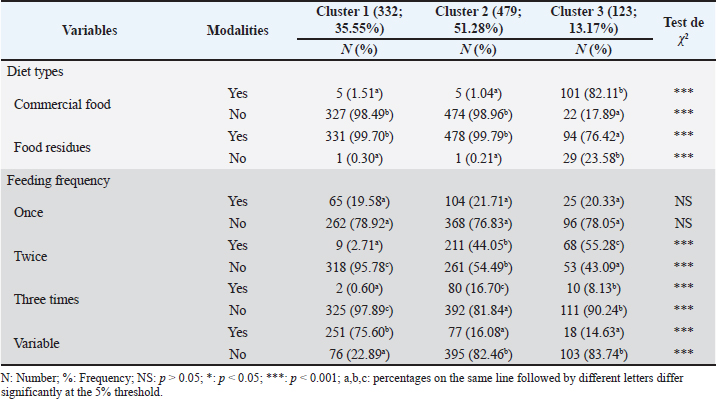

Table 2. Modality frequencies of variables related to dog breeding practices.

Table 2a. Modality frequencies of variables related to dog breeding practices (Continued).

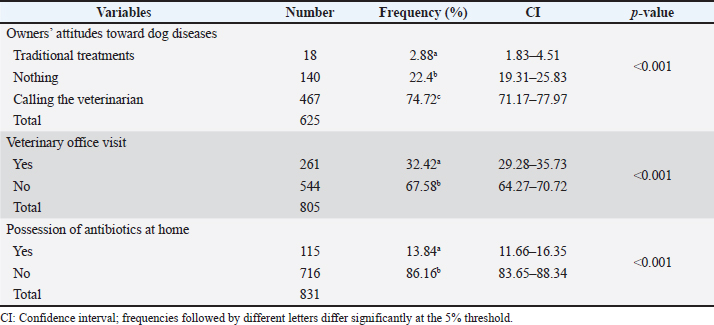

Table 3. Modality frequencies of variables related to dog owners’ management of dog diseases.

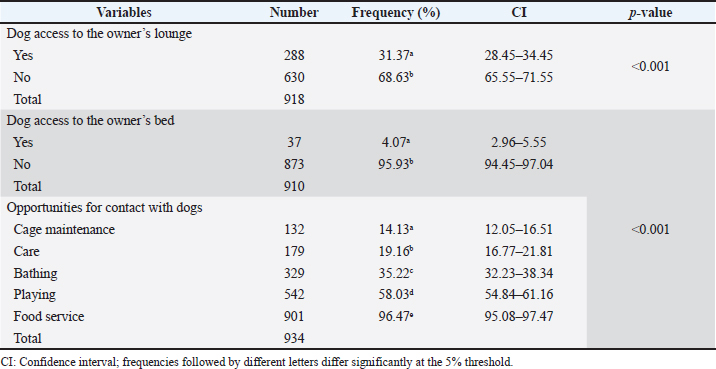

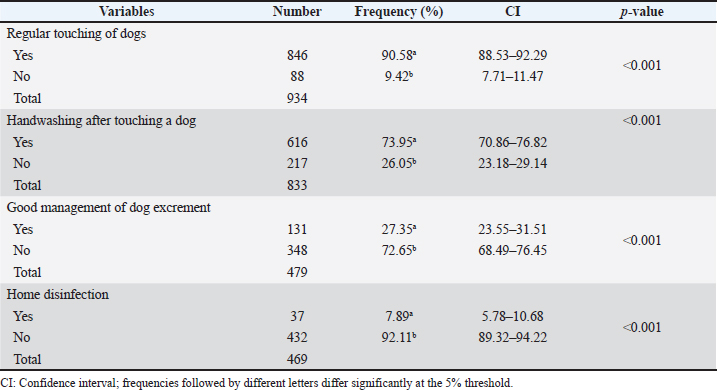

Table 4. Modality frequencies of variables relating to contact opportunities with dogs and hygiene practices of dog owners.

Contacts with dogs and the hygiene practices of dog ownersTable 4 shows that in some households, dogs had access to their owners’ living rooms or beds. Respondents were more likely to come into contact with their dogs when feeding them than when playing, bathing, taking care of their health, or maintaining their dog’s kennel or crate. Almost 91% of those surveyed acknowledged that they frequently touched their dogs, but around 74% of them washed their hands after touching the animals. Dog excrement was well managed by less than 30% of respondents. A low frequency of respondents disinfected their homes. Table 4a. Modality frequencies of variables relating to contact opportunities with dogs and hygiene practices of dog owners (Continued).

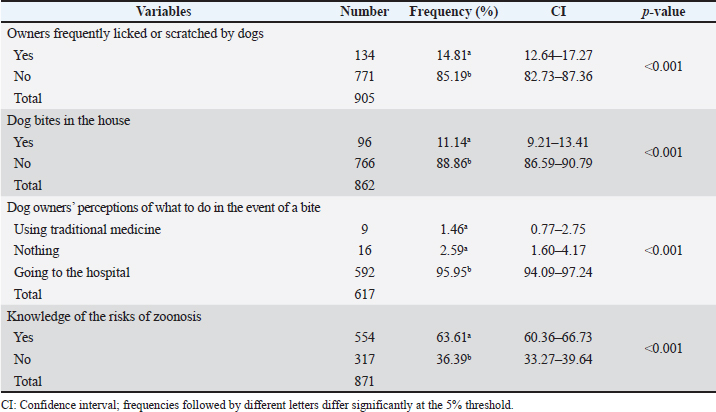

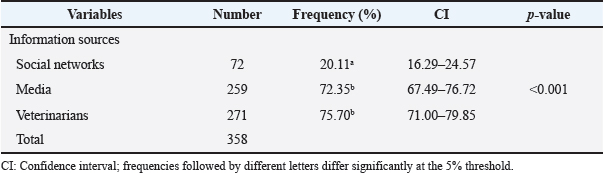

Table 5. Modality frequencies of variables related to dog owners’ attitudes and knowledge about zoonosis risks.

Dog owners’ attitudes and knowledge about zoonosis risksAccording to Table 5, almost 15% of respondents said they were frequently licked or scratched by their dogs. Bites were also recorded in households with 11.14% of the respondents. Regarding respondents’ perception of what to do in the event of a bite, a significantly high frequency of respondents indicated that they would go or take the victim to the hospital in the event of a bite. Significantly more dog owners were aware of the possibility of microorganisms being exchanged between themselves and their dogs than were unaware of this risk. This knowledge was acquired more via veterinarians and the media than via social networks. Table 5a. Modality frequencies of variables relating to dog owners’ attitudes and knowledge about zoonosis risks (Continued).

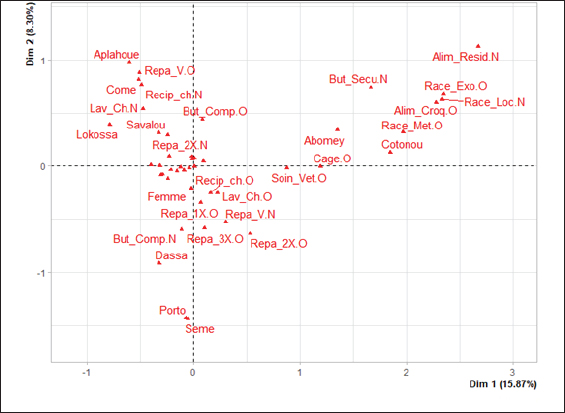

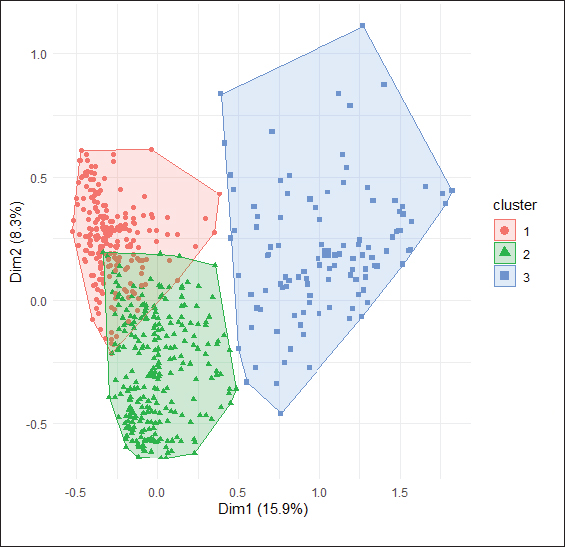

Fig. 1. Plot of the ACM on owners’ socio-demographic characteristics and dog breeding practices. Repa_V.O: The frequency of meals given to the dogs per day is variable “Yes”; Recip_ch. N: The dogs’ meals are served in specific containers “No”; Lav_Ch. N: Washing of the dogs by the owners “No”; But_Comp. O: The purpose of breeding the dogs is companionship “Yes”; Repa_2X. N: The frequency of meals served to dogs is two “No”; Abomey: Abomey-Calavi; Cage. O: Dogs are housed in a cage “Yes”; But_Secu. N: The purpose of breeding dogs is safety “Yes”; Alim_Resid. N: The meals given to dogs are food residues “No”; Race_Exo. O: The breed of dogs bred is the exotic breed “Yes”; Race_Loc. N: The breed of dogs bred is the local breed “No”; Alim_Croq. O: The meals given to the dogs are commercial food “Yes”; Race_Met. O:: The breed of dogs bred is mixed breed “Yes”; Recip_ch. O: The dogs’ meals are served in specific containers “Yes”; Soin_Vet. O : Dogs are cared for by a veterinarian “ Yes ‘ ; Lav_Ch. O : Dogs are washed by their owners ‘ Yes’; Repa_1X.O : Dogs are fed once a day ’ Yes ‘ ; Repa_V.N : Dogs are fed variable meals a day ’ No ‘ ; But_Comp. N : Dogs are bred for companionship “No ” ; Repa_3X.O: Frequency of meals given to dogs per day is three times “Yes”; Repa_2X.O: Frequency of meals given to dogs per day is twice “Yes”; Dassa: Dassa-Zoumé; Porto: Porto-Novo. Relationships between the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their dog breeding practicesThe MCA of the variables allowed for the representation of the modalities of the variables relating to the socio-demographic characteristics of dog owners and their dog breeding practices in a two-dimensional space (Fig 1). The first two dimensions (axes) of Figure 1, which explain 24.17% of the total variation, enabled relative discrimination of dog owners’ breeding practices. Hierarchical clustering enabled us to distinguish 3 groups or clusters (Fig 2). The percentages of the distribution of the variable modalities are presented in Table 6.

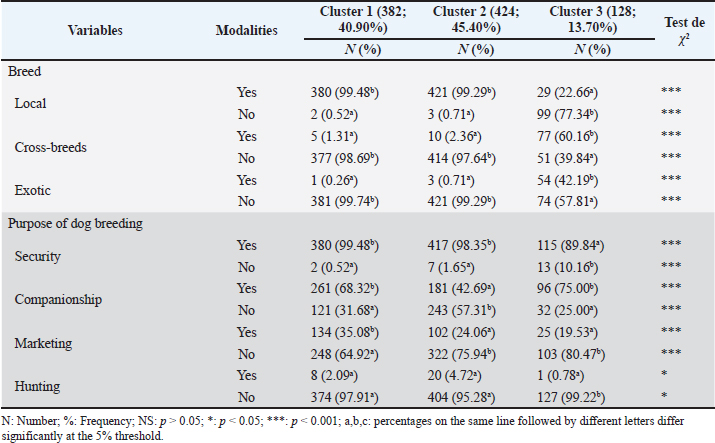

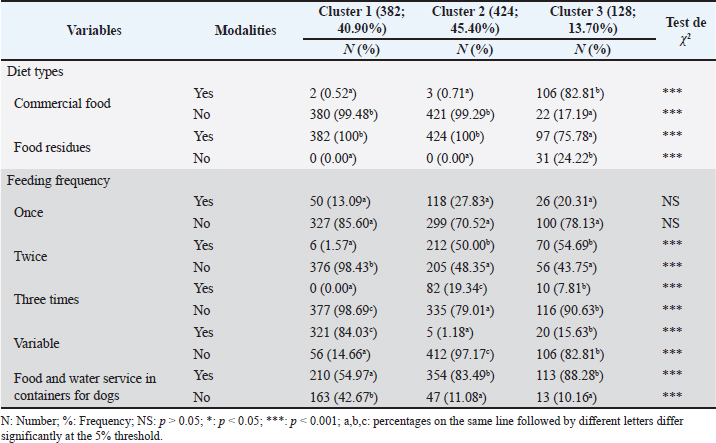

Fig. 2. Graphic representation of clusters relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their dog breeding practices. Table 6. Modality frequencies for variables on dog-owner sociodemographic characteristics and dog-breeding practices by group (clusters).

Table 6a. Modality frequencies for variables on dog-owner sociodemographic characteristics and dog-breeding practices by group (clusters) (Continued).

Table 6b. Modality frequencies for variables on dog-owner sociodemographic characteristics and dog-breeding practices by group (clusters) (Continued).

Table 6c. Modality frequencies for variables on dog-owner sociodemographic characteristics and dog-breeding practices by group (clusters) (Continued).

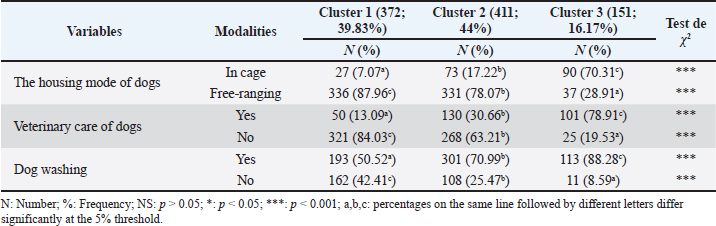

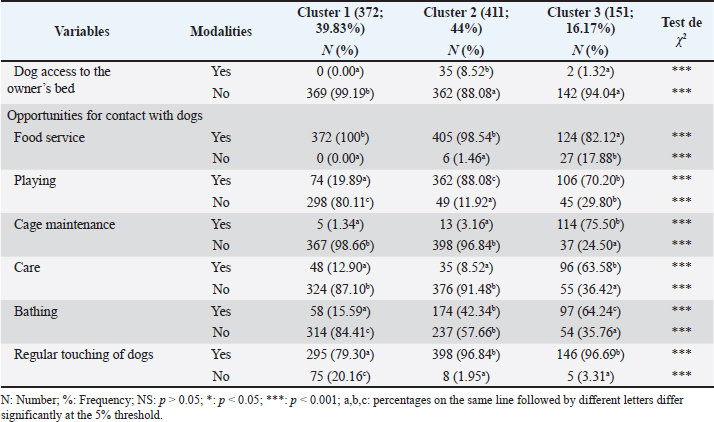

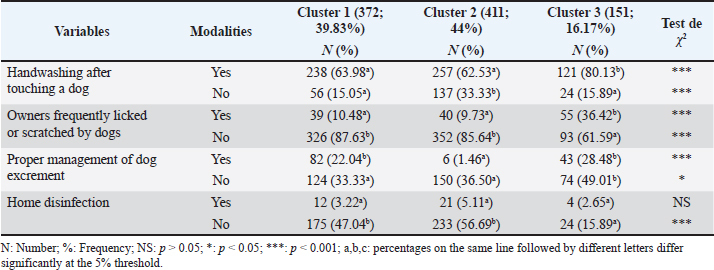

Group 1 (cluster 1) consisted of dog owners living in Aplahoué, Comé, Lokossa, Parakou, and Savalou. These owners mainly bred local dogs for household security, companionship, and marketing. This group was characterized by a high proportion of owners who fed their dogs with varying frequency. Meals often consisted of food residues and were not served in a specific container. Dogs were raised free-range in the home, and owners did not hire a veterinarian to monitor their health, nor did they wash their animals. Group 2 (Cluster 2) consisted of dog owners residing in Dassa-Zoumé, Parakou, Porto-Novo, Savalou, and Sèmè-Podji. They primarily bred local dogs. The dogs were mainly kept for household security and hunting purposes. Owners typically fed their dogs two or three meals of residue food, served in special containers. The use of commercial dog food was less common among owners in this group. They did not hire a veterinarian to monitor their animals’ health and did not wash them. Group 3 (Cluster 3) consisted of dog owners living in Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, and Sèmè-Podji. They mainly owned cross-breed dogs as well as foreign breeds. This group was characterized by the breeding of companionship dogs. Owners typically fed their dogs two meals a day, consisting of commercial dog food rather than food residues. They usually served their meals in appropriate containers for their dogs. The dogs were housed in cages, and the owners hired a veterinarian to monitor their health. Additionally, these owners periodically bathed their dogs. Relationships between the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their hygiene practices when breeding dogsThe results of the MCA revealed relationships between the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their hygiene practices when raising dogs (Fig 3). The first two dimensions of Figure 3, which explain 22.63% of the total variation in the MCA, allowed for relative discrimination of dog owners based on their hygiene practices. Hierarchical clustering enabled the identification of three groups or clusters (Fig 4). The percentages of the distribution of the variable modalities are presented in Table 7.

Fig. 3. ACM graph of the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their hygiene practices. Att_ch. N: Regular touching of dogs “No”; Occaz_Amuz. N: Frequent contact with dogs is for fun “No”; Dassa: Dassa-Zoumé; Ch_salon. N: Dog enters owner’s living room “No”; Lav_mains. O: Hands washed after touching dogs “Yes”; Occaz_Entret. O: The occasion of frequent contact with the dogs is the maintenance period of the doghouse or cage “ Yes ‘ ; Abomey : Abomey-Calavi ; Occaz_Alim. N: The occasion of frequent contact with the dogs is the service of food to the dogs ’ No ” ; Occaz_Soin. O: The occasion for frequent contact with dogs is the dog care period “Yes”; Grif_Lech. O: Owner frequently licked or scratched by dogs “Yes”; Occaz_Bain. N: The occasion for frequent contact with dogs is the dog bath period “No”; Ch_lit. N: The dog has access to the owner’s bed “No” ; Occaz_Entret. N: The occasion of frequent contact with dogs is the dog kennel or cage maintenance period “No” ; Occaz_Soin. N: : The occasion of frequent contact with dogs is the dog care period “No” ; Lav_mains. N: Washing hands after being touched by dogs “ No” ; Grif_Lech. N: Owner frequently licked or scratched by dogs ’ No ‘ ; Occaz_Bain. O: The occasion for frequent contact with dogs is bath time “Yes ” ; Att_ch. O: Dogs regularly give birth “Yes”; Occaz_Amuz. O: The occasion for frequent contact with dogs is fun “Yes”; Porto: Porto-Novo; Ch_salon. O: The dog has access to the owner’s living room “Yes”; Ch_lit. O: The dog has access to the owner’s bed “Yes”.

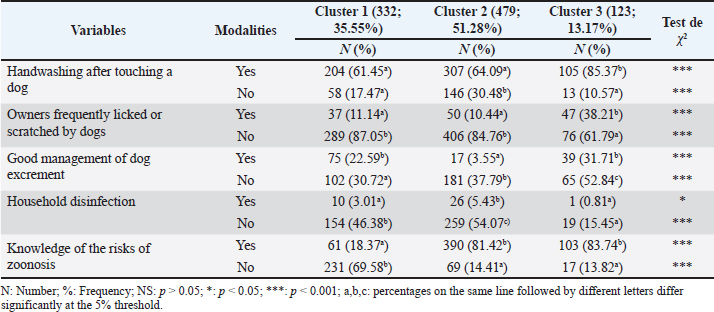

Fig. 4. Graphic representation of clusters relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their hygiene practices (cluster 1 in red, cluster 2 in green and cluster 3 in blue). Table 7. Modality frequencies of variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their practices by group (clusters).

Table 7a. Modality frequencies of variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their practices by group (clusters) (Continued).

Table 7b. Modality frequencies of variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners and their practices by group (clusters) (Continued).

Group 1 (Cluster 1) included owners living in Aplahoué, Comé, Dassa-Zoumé, and Lokossa. These were male individuals who did not allow their dogs into their living rooms. These owners came into contact with their dogs mainly at mealtimes, but playtime, maintenance of the dog’s cage, grooming, or bathing were not occasions for close physical contact with them. They did not frequently touch their dogs, nor were they often licked or scratched by them. They managed their dogs’ excrement properly but did not disinfect their homes. Group 2 (Cluster 2) comprised women who were accustomed to allowing their dogs into their bedrooms. They were located in Parakou, Porto-Novo, Savalou, and Sèmè-Podji. Opportunities for close physical contact with dogs were mainly associated with fun rather than moments of care. These owners frequently touched their dogs but did not wash their hands after these interactions. They were not often licked or scratched by their dogs and did not disinfect their homes. Group 3 (cluster 3) comprised mostly male individuals living in Abomey-Calavi and Cotonou. They came into close contact with their animals during dog kennel or cage maintenance, as well as during care and bathing, but not during feeding or playtime. They often touched their dogs and washed their hands after touching them. In addition, these owners were often licked and scratched by their dogs and properly managed their dogs’ excrement. Relationships between the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risksThe MCA results revealed relationships between dog owners’ sociodemographic characteristics, breeding practices, attitudes, and knowledge about zoonosis risks (Fig 5). The first two dimensions explained 22.79% of the total variation and enabled relative discrimination between dog owners. Hierarchical clustering enabled us to distinguish three groups or clusters (Fig 6). The percentages of the distribution of the variable modalities are presented in Table 8.

Fig. 5. Plot of the ACM on the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks. Att_ch. N: Regular touching of dogs “No”; Recip_ch. N: Dog meals are served in special containers “No”; Con_EchMicro. N: Knowledge of microorganism exchange “No”; Occaz_Amuz. N: Frequent contact with dogs is fun “No”; Ch_salon. N: The dog has access to the owner’s living room “No”; Lav_mains. N: Washing of hands after touching dogs “No”; Repa_2X.N: The frequency of meals served to dogs is two “No”; Occaz_Bain. N: The occasion for frequent contact with dogs is the dog bathing period “No”; Alim_Resid. N: The meals given to the dogs are food residues “No”; Race_Exo. O: The breed of dogs bred is the exotic breed “Yes”; Alim_Croq. O: The meals given to the dogs are commercial foods “Yes”; Race_Loc. N: The breed of dogs bred is the local breed “No”; Race_Met. O: The breed of dogs bred is mixed breed “ Yes ‘ ; Abomey : Abomey Calavi ; Occaz_Entret. O: The occasion of frequent contact with dogs is the period of maintenance of the dogs’ kennel or cage “Yes”; Cage. O:Housing of the dogs in a cage “Yes”; Occaz_Soin. O: The occasion of frequent contact with dogs is the period of care of dogs ‘ Yes ’; Soin_Vet. N: Follow-up of dogs by a veterinarian “ No” ; Soin_Vet. O: Follow-up of the dogs by a veterinarian ’ Yes ‘; Occaz_Bain. O: The occasion of frequent contact with dogs is the dog’s bathing period “Yes”; Repa_V.N : The frequency of meals given to the dogs per day is variable“No” ; Occaz_Amuz. O: The occasion for frequent contact with the dogs is amusement “Yes”; Repa_2X.O: The frequency of meals given to the dogs per day is twice “Yes”; Ch_salon. O: The dog has access to the owner’s living room “Yes”; Porto: Porto-Novo; Con_EchMicro. O: Knowledge of the exchange of microorganisms “Yes”

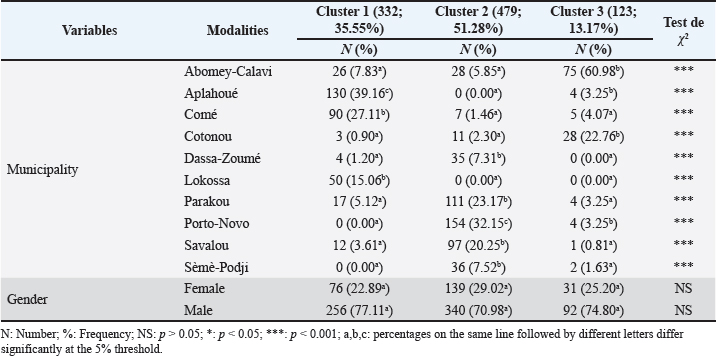

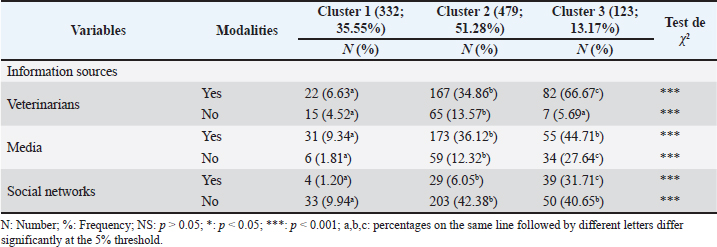

Fig. 6. Graphic representation of clusters relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog-breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge of zoonosis risks (cluster 1 in red, cluster 2 in green and cluster 3 in blue). Table 8. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks.

Table 8a. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks (Continued).

Table 8b. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks (Continued).

Table 8c. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks (Continued).

Table 8d. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks (Continued).

Table 8e. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks (Continued).

Table 8f. Modality frequencies for variables relating to the sociodemographic characteristics of dog owners, their dog breeding practices, and their attitudes and knowledge regarding zoonosis risks (Continued).

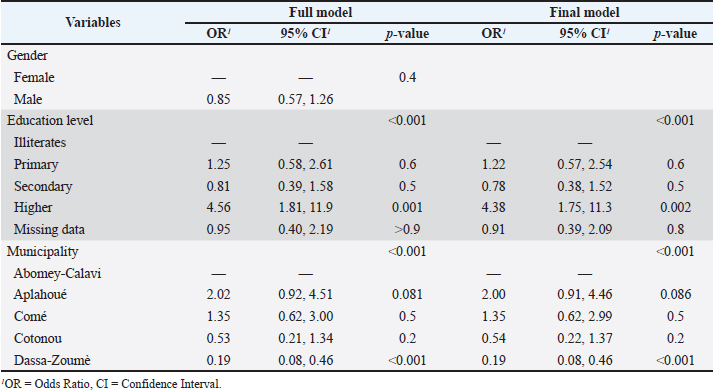

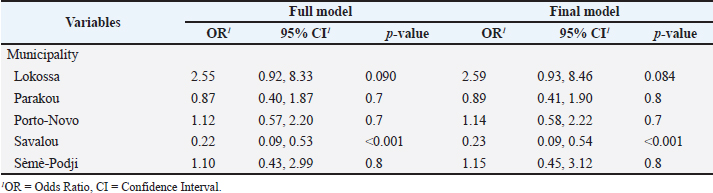

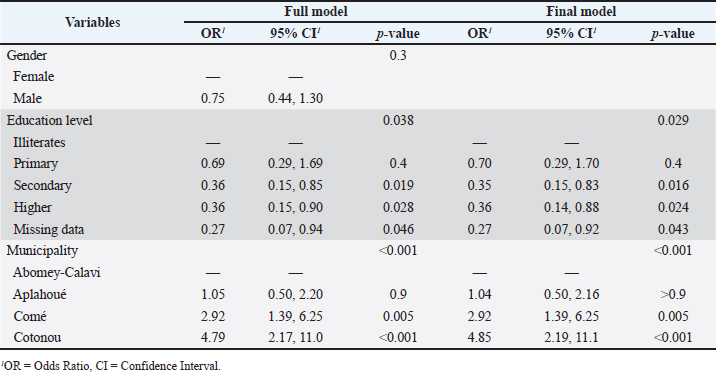

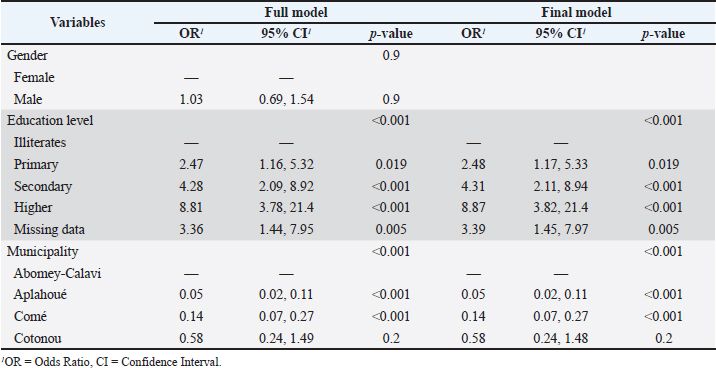

Group 1 (Cluster 1) included dog owners living in Aplahoué, Comé, and Lokossa. They mainly bred local dogs. They aimed to ensure household security and to market the dogs. Members of this group generally fed their dogs’ residual food rather than commercial food. The frequency of meals varied, and meals were not often served in a specific container. The owners raised their dogs freely within their households and did not hire a veterinarian to monitor their dogs’ health. They sometimes washed their dogs. The dogs had no access to the owners’ bedrooms or beds. They approached their dogs when meals were being served. They did not frequently touch their dogs and did not allow themselves to be licked or scratched by them. Dog owners in this category had no knowledge of the risks of zoonosis. Group 2 (cluster 2) consisted of dog owners living in Dassa-Zoumé, Parakou, Porto-Novo, Savalou, and Sèmè-Podji. They are breeders of local dogs. They bred dogs for household security, not for companionship or marketing. They did not feed the dogs with residual food, but commercial food and meals were often served three times a day. In this group, the dogs had access to both the living room and the bed of their owners. They approached their dogs during meal service and playtime. They did not wash their dogs after touching them. This group included owners who were not frequently licked or scratched by their dogs. Household disinfection was not a frequent practice among these owners. They were informed about the risks of zoonosis via the media. Group 3 (cluster 3) included dog owners living in Abomey-Calavi and Cotonou. Breeding cross-breeds and exotic dog breeding characterized these owners. This group was distinguished from the others by a higher proportion of those who bred dogs for companionship, without breeding for safety or marketing. They fed their dogs twice a day with commercial food without using any food residue. Meals were served in containers suitable for dogs. Owners in this category housed their dogs in cages, hired a veterinarian to monitor their dogs’ health, and washed them periodically. The dogs had access to the owners’ living room. On the other hand, owners did not frequently come into contact with their dogs at mealtimes, but rather during playtime, kennel or cage maintenance, grooming, or bathing. They frequently touched their dogs and washed their hands after touching them. These owners were also often licked or scratched by their dogs. Some dogs’ excrement was managed properly, while others did not. These owners were aware of the risks of zoonosis, whether through vets, social networks, and the media or not. Factors associated with dog owners’ hygiene practicesTable 9 analysis reveals a significant effect of education level and municipality on handwashing after touching dogs. Dog owners with higher education levels were 4.56 times more likely to wash their hands after contact with their dogs, and those with primary education levels were 1.22 times more likely to observe this hygiene practice, according to the final model. Dog owners living in Lokossa were 2.59 times more likely to wash their hands after touching their dogs; those in Aplahoué, Comé, Porto-Novo, and Sèmè-Podji were 2.0, 1.35, 1.14, and 1.15 times more likely, respectively. A significant effect of education level and municipality on the good management of dog excrement was also observed (Table 10). The education level did not increase the likelihood of good management of dog excrement. On the other hand, at the municipality level, dog owners living in Cotonou were 4.85 times more likely to manage dog excrement well, while those in Comé, Lokossa, and Aplahoué were 2.92, 1.59, and 1.04 times more likely to observe good excrement management practice, respectively, and those in other municipalities were less likely to do so. Table 9. Effects of gender, education level, and municipality on handwashing after dog touching.

Table 9a. Effects of gender, education level, and municipality on handwashing after dog touching.

Table 10. Effect of sex, education level, and municipality on the good management of dog excrement.

Table 10a. Effect of sex, education level, and municipality on the good management of dog excrement.

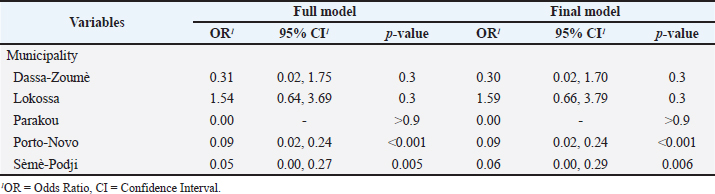

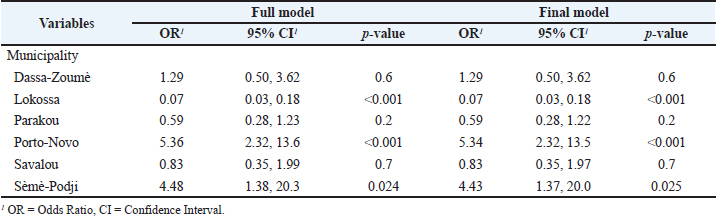

According to Table 11, the education level and municipality of the respondents had a significant effect on the knowledge of zoonosis risks between dogs and those around them. The higher the education level, the greater the chance of knowing about zoonosis risks between dogs and their owners. In terms of municipalities, dog owners living in Porto-Novo (5.34), Sèmè-Podji (4.43), and Dassa-Zoumè (1.29) were more likely to have knowledge about zoonosis risks than those living in the other municipalities. Table 11. Effect of sex, education level, and municipality on knowledge of zoonosis risks between dogs and their owners.

Table 11a. Effect of sex, education level, and municipality on knowledge of zoonosis risks between dogs and their owners.

DiscussionThe exchange of zoonotic agents between humans and animals, particularly pets such as dogs, is a reality. The dog management and hygiene practices of those who have close and frequent physical contact with dogs play an important role in increasing or reducing the risk of pathogen zoonosis. This study was devoted to describing the characteristics of dog breeding and the hygiene practices of dog owners in Benin municipalities. This study shows that in Benin, households owning local dogs are more frequent than those owning foreign breeds, and dog owners are more likely to be found in Aplahoué, Comé, Dassa-Zoumé, Lokossa, Parakou, Porto-Novo, Savalou, and Sèmè-Podji. Several reasons were given by respondents to justify the choice of local breeds: their availability on the market, the lower purchase price, the ease of feeding them, and their resistance to certain diseases compared to foreign breeds. In the present study, household security was the main purpose of dog ownership, as indicated by the respondents. This result is in line with those reported in Rwanda, where a high frequency (93.1%) of respondents breeding dogs for security reasons was recorded (Ntampaka et al., 2022). In contrast, a survey conducted in three European countries revealed a high percentage of owners owning dogs for pleasure and companionship: 85.5% in Bulgaria, 87.7% in Italy, and 70.7% in Ukraine (Smith et al., 2022). In Nigeria, dog owners who bred dogs for hunting were more common (42%) than breeders of dogs for companionship, safety, and reproduction (40%) (Daodu et al., 2017). In New Zealand, the main reason for dog ownership was companionship (40.6%) (Gates et al., 2019a). These differences in results reveal, on the one hand, that the purpose of dog ownership can vary from one owner to another, from one country to another, and on the other hand, the diversity of the role of dogs in a household. The difference between the different groups of dog owners surveyed in this study confirms the variation in the purpose of dog ownership. In this study, a significant variation in the frequency of dog feeding was noted, particularly among dog owners belonging to group 1. However, feeding dogs twice a day is considered a standard of good feeding practice (Eastland-Jones et al., 2014; Koh et al., 2020). This practice is frequent in dog owners from groups 2 and 3. These results are consistent with those recorded in Australia (Bland et al., 2009), the USA (Koh et al., 2020), and the US (Kluess and Jones, 2023), with high frequencies of owners feeding their dogs twice a day. By contrast, in Sylhet, Bangladesh, 55% of respondents fed their dogs three times a day, 35% did so twice a day, and 10% served them one meal a day (Chowdhury et al., 2020). This study revealed that a good number of dog owners in Benin respect good feeding practices for dogs in terms of meal frequency. Regarding the food given to dogs, this study showed that respondents fed their dogs both commercial food and food residues. Commercial foods included kibbles and foods formulated by veterinarians for dogs and placed on the market. The food residues consisted of kitchen scraps, a mixture of paste made from maize flour and sauce, a mixture of rice with bone or meat, or a mixture of bone and meat. Residual food was given more to dogs by owners in groups 1 and 2, and commercial food was given to dogs by those in group 3, showing a variation in the food given to dogs according to the dog owner group. The diversity of dog foods can also be observed in other countries. In New Zealand, food residues (50.1%), meats (37%), and owner-prepared foods are fed to dogs (Gates et al., 2019a). In Bangladesh, kitchen scraps, rice, home-formulated foods, and commercial foods are given to dogs (Chowdhury et al., 2020). In Sri Lanka, 42% of owners fed their dogs only with home-made food, 18% fed them with commercial food, and 40% fed them with a mixture of commercial and home-made food (Seneviratne et al., 2016). In the USA, 60.50% of respondents served commercial kibble or canned food to their dogs, while 16.8% fed them a mixture of commercial and home-prepared or raw foods, 12.50% fed them non-traditional commercial foods (mainly raw, freeze-dried) and 10.20% fed them home-prepared or raw foods (Koh et al., 2020). These differences in the amount of food given to dogs are thought to be linked to differences in geographical location, the socioeconomic conditions of dog owners, or the breed of dog that is raised. In the present study, almost 76% of respondents had containers in which they served only food to their dogs. This percentage is twice as high as that reported in Rwanda (33.5%) (Ntampaka et al., 2022). Serving meals in a clean container suitable for dogs is a practice that would contribute to reducing the contamination risk of dog meals by environmental pathogens agents and would preserve not only the health of dogs, but also that of all those who come into contact with them. It is worth considering raising awareness among dog owners, so that they can all adopt the correct practice of serving meals to their dogs. Regarding how dogs are housed, a high frequency of respondents raising dogs in the free-ranging category was recorded, especially among owners in groups 1 and 2. As dogs are reservoirs of many zoonotic pathogens, this high frequency reveals the risk of spreading microorganisms in the environment, and more specifically in the yard, living room, bed, or any other place where infected dogs could access. Free-range dog husbandry can also increase the number of bites and scratches, which are considered opportunities for the transmission of microorganisms to survivors. The housing of dogs in cages should be encouraged by raising awareness among dog owners, especially those in Aplahoué, Comé, and Lokossa. Some microorganisms can live for a long time in the environment (Oludairo et al., 2022). Regular disinfection of households with free-ranging dogs can help eliminate these microorganisms. However, this study revealed a low percentage of owners of free-ranging dogs (7.89%) disinfecting their homes. The main reason for disinfecting the houses was the invasion of homes by ticks and fleas that had infested their dogs. Disinfection is usually performed by a veterinarian or paravet using acaricides. There is a need to raise awareness among dog owners of the importance of regular disinfection of homes where dogs are raised in free range. The results of the present study reveal that 31.40% of owners have hired veterinarians to monitor their dogs. This practice was more frequent among owners in group 3, who lived in Abomey-Calavi and Cotonou. This is a part of good animal husbandry practice and helps prevent disease. Dog owners belonging to groups 1 and 2 need to be encouraged to hire an animal health agent to monitor their dogs to safeguard the health of both dogs and humans. Furthermore, a high frequency of owners washing their dogs was recorded in this study. Some owners bathe their dogs once or twice a month, others once a quarter. Some owners bathe their dogs using ordinary soaps intended for human use, while others hire a veterinarian or paravet to bathe their dogs. Dog washing was more marked in groups 2 and 3, suggesting that group 1 dog owners are becoming more aware of the importance of washing their dogs frequently. Animals can be colonized by multiresistant bacteria, often without showing signs of sickness due to these organisms (Sykes and Weese, 2014). In contact with these animals, owners may carry these organisms on their hands and clothing (Sykes and Weese, 2014). Given that 90.58% of dog owners frequently touch their dogs, frequent dog washing would help to reduce the population of microorganisms on the dogs’ skin and would probably reduce the population of pathogens that would contaminate those who touched them. In their daily relationships with their dogs, owners engage in practices that reveal their hygiene practices in caring for their dogs. This study showed that owners had more physical contact with their dogs during food service (96.58%). Given that feeding frequently takes place twice a day, owners have twice the opportunity to exchange microorganisms with their dogs. In Nigeria, 82% of owners come into close contact with their dogs, mainly during playtime (Daodu et al., 2017). This frequency is higher than that recorded in this study for owners who frequently came into contact with their dogs during playtime (58.03%). This difference in contact opportunities may be linked to the different countries in which the studies were conducted. In this study, the frequency of dog owners reporting being frequently scratched or bitten by their dogs was 14.8%. This percentage is higher than the 10.6% reported in Belgium, where dog owners were often bitten by their dogs during playtime or dog aggression (Joosten et al., 2020). In Ontario, Canada, 37% and 10% of respondents owning dogs or cats, respectively, responded that they had been scratched and bitten by their pets in the 12 months before the survey (Stull et al., 2012). In previous surveys, dog bites and scratches were recognized as rabies transmission modes (Li et al., 2021; Spargo et al., 2021). Transmission of the rabies virus occurs through contact between infectious saliva and injured skin or mucous membranes, generally by biting, but also by scratching or licking (Fisher et al., 2018). Additionally, bacteria such as Bacillus spp, Pseudomonas spp, Staphylococcus spp, Streptococcus spp, Aeromonas spp, Burkholderia spp, Citrobacter spp, Escherichia spp, and so on, were detected in the dogs’ buccal swabs (Awoyomi and Ojo, 2014). Dog scratches and bites are not without risk to human health. It is essential to regularly educate dog owners on how to prevent or better manage dog scratches and bites. Regular awareness-raising on how to prevent or better manage dog scratches and bites is essential, especially for dog owners living in Abomey-Calavi and Cotonou, where the proportion of those who reported being often licked or scratched was significantly high. Handwashing is a key element of good hygiene practices at home and in the community, leading to a significant reduction in the number of organisms potentially responsible for infections, in particular gastrointestinal infections, but also respiratory tract and skin infections (Bloomfield et al., 2007; Lal, 2015;). This study revealed that a good number of dog owners in Benin wash their hands after touching their dogs, especially those living in Abomey-Calavi and Cotonou. Hand hygiene practices are also observed in Rwanda, where out of 203 surveyed dog owners, nearly 62% said they washed their hands after touching their dogs (Ntampaka et al., 2022). In Ireland, 18% of dog owners said that they always washed their hands after touching their dogs, while 67% did so sometimes (Sherlock et al., 2023). The high frequency of participants washing their hands after touching dogs recorded in this study could be linked to the multiple awareness-raising sessions on hygiene measures during the COVID-19 period. On the other hand, handwashing after touching dogs is less common among owners with secondary education levels who live mainly in Cotonou, Dassa-Zoumè, Parakou, and Savalou. To improve the percentage of those who observed good hand hygiene practices, awareness-raising programs need to be developed and implemented for dog owners living in Aplahoué, Comé, Dassa-Zoumé, Lokossa, Parakou, Porto-Novo, Savalou, and Sèmè-Podji. Regarding visits to veterinary practices, 32.42% of respondents observed such practices for various reasons (medical check-ups of their dogs, vaccination, and health care). The same reasons were cited by dog owners surveyed in Korea (Kim et al., 2020) and New Zealand (Gates et al., 2019a). In New Zealand, 93.7% of owners considered it unnecessary to send their dogs to veterinarians for care; others cited cost (17.7%), the absence of veterinarians in their locality (1.3%), or accessibility of veterinarians (2.5%) as reasons for not taking their dogs to vets (Gates et al., 2019a). Raising dog owners’ awareness of the importance of having their dogs seen regularly, reducing consultation fees, and installing practices in areas where there are none will help to improve the percentage of owners who bring their dogs to veterinary practices for consultation or treatment. In this study, dog owners’ perceptions about the management of bite cases varied, but a high frequency of those who said they would go or drive the victim to the hospital was noted (95.95%). In Morocco, 70.80% of dog owners stated that they would visit the hospital (Bouaddi et al., 2020). These frequencies although high, deserve improvement because dog bites can cause diseases and death if precautions are not taken in time. Dog excrement plays a role in the transmission and spread of microorganisms in the environment. In southern Italy, multiresistant Enterococcus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains were isolated from samples of dog excrement collected in the streets (Cinquepalmi et al., 2013). Good management practices of dog excrement are also important for preventing the spread of pathogens in the environment. In this study, 27.35% of the owners observed that practices consist of disposing of excrement in a specific bin in a septic tank or burying it in the ground. In Ireland, 71% of respondents threw dog excrement in a bin (Sherlock et al., 2023). Dog owners, especially those living in the municipalities of Dassa-Zoumè, Parakou, Porto-Novo, Savalou, and Sèmè-Podji, where this practice was less common, need to be sensitized to improve the percentage of those practicing good dog excrement management. In the current study, a high frequency of dog owners (63.61%) were aware that they could contract diseases by approaching their dogs. This knowledge was acquired from veterinarians, via the media, or through social networks. These results show that veterinarians, the media, and social networks can be used to increase dog owners’ awareness about the risks of pathogens exchange. Dog owners surveyed in the municipalities of Aplahoué, Comé, and Lokossa were less informed about the risks of microorganism exchange. Urgent awareness-raising programs need to be implemented, especially in these municipalities. ConclusionThis study addressed two important points regarding the management of zoonosis risks between dogs and those who come into contact with them. These are the dog management and hygiene practices of the dog owners. The study shows that local dogs are more common in households than foreign dog’s breeds. Dogs are more bred for household security than for companionship, marketing, and hunting. Many dog owners observe good animal welfare practices (feeding, housing, body and health care, and so on). All dog owners are not aware of the microorganism exchange risks between themselves and their pets, and they do not practice good hygiene practices. Consequently, awareness raising and training programs for dog owners on good hygiene practices after contact with their animals, the good management of their animals’ excrement, and the microorganism exchange risks must be developed and implemented to prevent effectively and to fight emerging zoonotic diseases. Veterinarians, media, and social networks will be involved in the implementation and success of these programs. AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank the URMAT/EPAC/UAC for the support. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. FundingThis work was supported by URMAT/EPAC/UAC. Author contributionsConceptualization, A.B.Y., N.N., and P.S.; methodology, A.B.Y., N.N., and P.S.; software, A.B.Y.; validation, A.B.Y., N.N., and P.S.; formal analysis, A.B.Y. and N.N.; investigation, A.B.Y., J.G., J-E.S., M.B.A., G.A.T., R.M.W., M.T.; data curation, A.B.Y. and N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.Y.; writing-review and editing, A.B.Y., N.N., P.A., L.B., S.F. and P.S.; visualization, P.S.; supervision, N.N., P.A., L.B., S.F. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Data availability Data supporting these findings are available within the article or upon request. ReferencesAwoyomi, O.J. and Ojo, O.E. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance in aerobic bacteria isolated from oral cavities of hunting dogs in rural areas of Ogun State, Nigeria. Sokoto J. Vet. Sci. 12, 47–51. Barnier, J., Biaudet, J., Briatte, F., Bouchet-Valat, M., Gallic, E., Giraud, F., Gombin, J., Kauffmann, M., Lalanne, C., Larmarange, J. and Robette, N. 2024. Introduction à l’analyse d’enquêtes avec R et RStudio. GitHub, p: 1193. Bhat, A.H. 2021. Bacterial zoonoses transmitted by household pets and as reservoirs of antimicrobial resistant bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 155, 104891. Bland, I.M., Guthrie-Jones, A., Taylor, R.D. and Hill, J. 2009. Dog obesity: owner attitudes and behaviour. Prev. Vet. Med. 92, 333–340. Bloomfield, S.F., Aiello, A.E., Cookson, B., O’Boyle, C. and Larson, E.L. 2007. The effectiveness of hand hygiene procedures in reducing the risks of infections in home and community settings including handwashing and alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Am. J. Infect. Control 35, S27–S64. Bouaddi, K., Bitar, A., Bouslikhane, M., Ferssiwi, A., Fitani, A. and Mshelbwala, P.P. 2020. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding rabies in El Jadida Region, Morocco. Vet. Sci. 7, 29. Carroll, K.C., Burnham, C.-A.D. and Westblade, L.F. 2021. From canines to humans: clinical importance of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009961. Chowdhury, Md.S.R., Hossain, Md.A., Islam, Md.R., Uddin, Md.B., Hossain, Md.M., Rahman, Md.M. and Rahman, Md.M. 2020. Management practices of pet dog among a representative sample of owners in Sylhet, Bangladesh. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 8, 819– 825. Cinquepalmi, V., Monno, R., Fumarola, L., Ventrella, G., Calia, C., Greco, M.F., de Vito, D. and Soleo, L. 2013. Environmental contamination by dog’s faeces: a public health problem? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 72–84. Costa, S.S., Ribeiro, R., Serrano, M., Oliveira, K., Ferreira, C., Leal, M., Pomba, C. and Couto, I. 2022. Staphylococcus aureus causing skin and soft tissue infections in companion animals: antimicrobial resistance profiles and clonal lineages. Antibiotics 11, 599. Daodu, O.B., Amosun, E.A. and Oluwayelu, D.O. 2017. Antibiotic resistance profiling and microbiota of the upper respiratory tract of apparently healthy dogs in Ibadan, South West, Nigeria. AJID 11, 1–11. Eastland-Jones, R.C., German, A.J., Holden, S.L., Biourge, V. and Pickavance, L.C. 2014. Owner misperception of canine body condition persists despite use of a body condition score chart. J. Nutr. Sci. 3, e45. Fisher, C.R., Streicker, D.G. and Schnell, M.J. 2018. The spread and evolution of rabies virus: conquering new frontiers. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 241–255. Gates, M., Walker, J., Zito, S. and Dale, A. 2019a. Cross-sectional survey of pet ownership, veterinary service utilisation, and pet-related expenditures in New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 67, 306–314. Gwenzi, W., Chaukura, N., Muisa-Zikali, N., Teta, C., Musvuugwa, T., Rzymski, P. and Abia, A.L.K. 2021. Insects, rodents, and pets as reservoirs, vectors, and sentinels of antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 10, 68. Hamame, A., Davoust, B., Rolain, J.-M. and Diene, S.M. 2022. Screening of colistin-resistant bacteria in domestic pets from France. Animals 12, 633. Joosten, P., Ceccarelli, D., Odent, E., Sarrazin, S., Graveland, H., Van Gompel, L., Battisti, A., Caprioli, A., Franco, A., Wagenaar, J.A., Mevius, D. and Dewulf, J. 2020. Antimicrobial usage and resistance in companion animals: a cross-sectional study in three European Countries. Antibiotics 9, 87. Kim, W.-H., Min, K.-D., Cho, S.-I. and Cho, S. 2020. The relationship between dog-related factors and owners’ attitudes toward pets: an exploratory cross- sectional study in Korea. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 493. Kluess, H.A. and Jones, R.L. 2023. A comparison of owner perceived and measured body condition, feeding and exercise in sport and pet dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 1211996. Koh, R., Montalbano, C., Gamble, L.J., Walden, K., Rouse, J., Liu, C.-C., Wakshlag, L.G. and Wakshlag, J.J. 2020. Internet survey of feeding, dietary supplement, and rehabilitative medical management use in flyball dogs. Can. Vet. J. 61, 375–381. Lal, M. 2015. Hand hygiene. Int. J. Curr. Res. 7, 13448–13449. Li, Y., Fernández, R., Durán, I., Molina-López, R.A. and Darwich, L. 2021. Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from cats and dogs from the Iberian Peninsula. Front. Microbiol. 11, 621597. Ntampaka, P., Niragire, F., Nkurunziza, V., Uwizeyimana, G. and Shyaka, A. 2022. Perceptions, attitudes and practices regarding canine zoonotic helminthiases among dog owners in Nyagatare district, Rwanda. Vet. Med. Sci. 8, 1378–1389. Oludairo, O., Kwaga, J., Kabir, J., Abdu, P., Gitanjali, A., Perrets, A., Cibin, V., Lettini, A. and Aiyedun, J. 2022. Review of Salmonella characteristics, history, taxonomy, nomenclature, non typhoidal salmonellosis (NTS) and typhoidal salmonellosis (TS). Zagazig Vet. J. 50, 160–171. OMS. 2016. Plan d’action mondial pour combattre la résistance aux antimicrobiens. Geneva: WHO. Available via https://www.who.int/fr/publications- detail/9789241509763 (Accessed 24 March 2024) Schulz, C., König, H.-H. and Hajek, A. 2020. Differences in self-esteem between cat owners, dog owners, and individuals without pets. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 552. Schwartz, D. 1995. Méthodes statistiques à l’usage des médecins et des biologistes. Paris, France: Editions médicales Flammarion, p: 314. Seneviratne, M., Subasinghe, D. and Watson, P. 2016. A survey of pet feeding practices of dog owners visiting a veterinary practice in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Vet. Med. Sci. 2, 106–116. Sherlock, C., Holland, C.V. and Keegan, J.D. 2023. Caring for canines: a survey of dog ownership and parasite control practices in Ireland. Vet. Sci. 10, 90. Smith, L.M., Quinnell, R., Munteanu, A., Hartmann, S., Villa, P.D. and Collins, L. 2022. Attitudes towards free-roaming dogs and dog ownership practices in Bulgaria, Italy, and Ukraine. PLoS One 17(3), e0252368. Spargo, R.M., Coetzer, A., Makuvadze, F.T., Chikerema, S.M., Chiwerere, V., Bhara, E. and Nel, L.H. 2021. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards rabies: a survey of the general population residing in the Harare Metropolitan Province of Zimbabwe. PLoS One 16, e0246103. Stull, J.W., Peregrine, A.S., Sargeant, J.M. and Weese, J.S. 2012. Household knowledge, attitudes and practices related to pet contact and associated zoonoses in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 12, 553. Sykes, J.E. and Weese, J.S. 2014. Infection control programs for dogs and cats. CFID, pp: 105–118. Yaovi, A.B., Sessou, P., Tonouhewa, A.B.N., Hounmanou, G.Y.M., Thomson, D., Pelle, R., Farougou, S. and Mitra, A. 2022. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria amongst dogs in Africa: a meta-analysis review. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 89, e1–e12. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Yaovi AB, Noudeke N, Gbaguidi J, Setondji J, Azon MB, Toni GA, Wankanrin RM, Tcheho M, Azokpota P, Baba-moussa L, Farougou S, Sessou P. Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 Web Style Yaovi AB, Noudeke N, Gbaguidi J, Setondji J, Azon MB, Toni GA, Wankanrin RM, Tcheho M, Azokpota P, Baba-moussa L, Farougou S, Sessou P. Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=243006 [Access: December 10, 2025]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Yaovi AB, Noudeke N, Gbaguidi J, Setondji J, Azon MB, Toni GA, Wankanrin RM, Tcheho M, Azokpota P, Baba-moussa L, Farougou S, Sessou P. Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Yaovi AB, Noudeke N, Gbaguidi J, Setondji J, Azon MB, Toni GA, Wankanrin RM, Tcheho M, Azokpota P, Baba-moussa L, Farougou S, Sessou P. Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited December 10, 2025]; 15(6): 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 Harvard Style Yaovi, A. B., Noudeke, . N., Gbaguidi, . J., Setondji, . J., Azon, . M. B., Toni, . G. A., Wankanrin, . R. M., Tcheho, . M., Azokpota, . P., Baba-moussa, . L., Farougou, . S. & Sessou, . P. (2025) Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 Turabian Style Yaovi, Ayaovi Bruno, Nestor Noudeke, Junior Gbaguidi, Jean-eudes Setondji, Mahugnon Bonaventure Azon, Gilles A. Toni, Rodrigue Mêmavo Wankanrin, Morel Tcheho, Paulin Azokpota, Lamine Baba-moussa, Souaïbou Farougou, and Philippe Sessou. 2025. Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 Chicago Style Yaovi, Ayaovi Bruno, Nestor Noudeke, Junior Gbaguidi, Jean-eudes Setondji, Mahugnon Bonaventure Azon, Gilles A. Toni, Rodrigue Mêmavo Wankanrin, Morel Tcheho, Paulin Azokpota, Lamine Baba-moussa, Souaïbou Farougou, and Philippe Sessou. "Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Yaovi, Ayaovi Bruno, Nestor Noudeke, Junior Gbaguidi, Jean-eudes Setondji, Mahugnon Bonaventure Azon, Gilles A. Toni, Rodrigue Mêmavo Wankanrin, Morel Tcheho, Paulin Azokpota, Lamine Baba-moussa, Souaïbou Farougou, and Philippe Sessou. "Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2626-2650. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Yaovi, A. B., Noudeke, . N., Gbaguidi, . J., Setondji, . J., Azon, . M. B., Toni, . G. A., Wankanrin, . R. M., Tcheho, . M., Azokpota, . P., Baba-moussa, . L., Farougou, . S. & Sessou, . P. (2025) Dog breeding practices, hygiene, attitudes, and knowledge of pet owners regarding zoonosis risks in Benin. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2626-2650. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.33 |