| Short Communication | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2895-2902 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2895-2902 Short Communication Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary resultsAndrea Núñez1,2**, Lisette Lapierre3, Beatriz Escobar3 and Rodrigo Castro4*1Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Universidad Católica del Maule, Curicó, Chile 2Dermatovet Talca, Clínica Veterinaria, Talca, Chile 3Departamento de Medicina Preventiva Animal, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile 4Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Recursos Naturales y Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Santo Tomás, Talca, Chile *Corresponding Author: Rodrigo Castro. Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Recursos Naturales y Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Santo Tomás, Talca, Chile. Email: rodrigocastro [at] santotomas.cl *Andrea Núñez. Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Universidad Católica del Maule, Curicó, Chile. Email: anunezb [at] ucm.cl Submitted: 20/02/2025 Revised: 10/05/2025 Accepted: 16/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

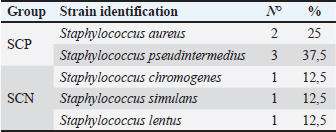

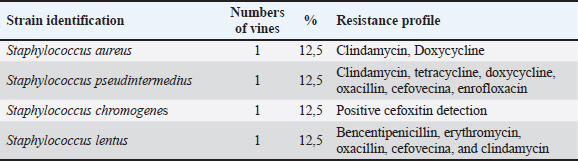

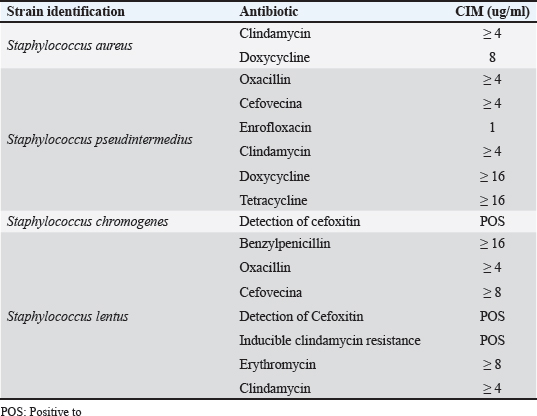

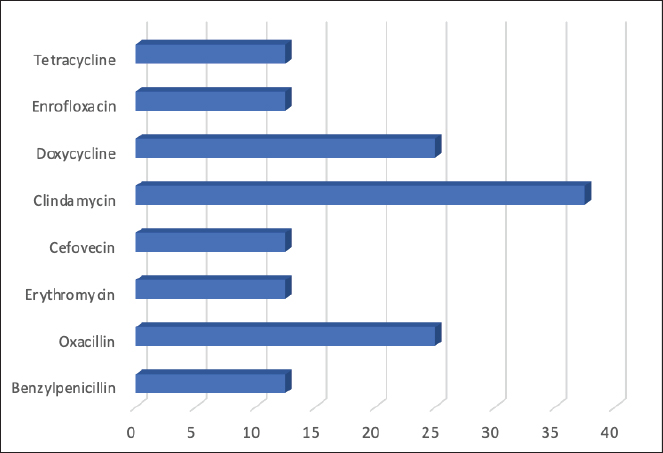

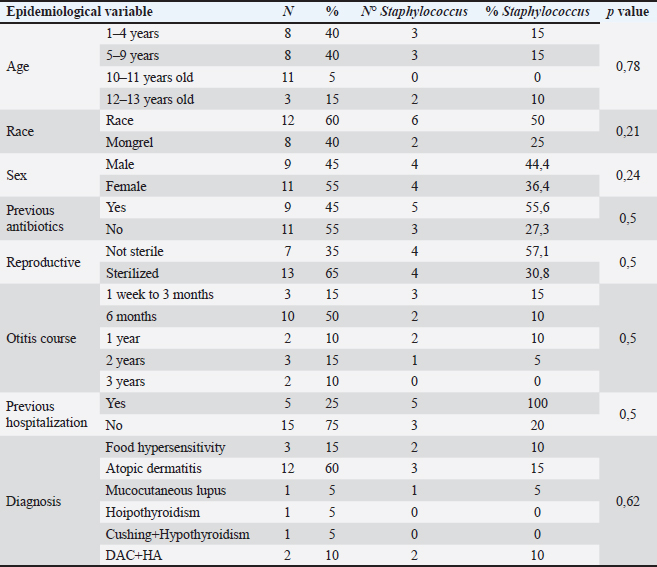

AbstractBackground: Otitis frequently affects dogs. Underlying diseases and predisposing factors affect the otic environment, thereby causing bacterial proliferation. One of the most isolated species in cases of otitis is the Staphylococcus genus, which has widely reported antimicrobial resistance profiles. This has not yet been studied in Talca, Chile. Aim: The objective of this study was to determine the existence of antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus strains isolated from the external auditory canal of a group of dogs diagnosed with otitis externa in Talca, Chile. Methods: Samples were taken from the external ear canal of 20 dogs with otitis externa from October 2023 to August 2024 at dermatological consultations in the city of Talca. The samples were transported to be processed and analyzed in the MICROVET Veterinary Microbiology laboratory, of the Faculty of Veterinary and Livestock Sciences of the University of Chile, using VITEK® 2 equipment for the identification and determination of antimicrobial susceptibility. The association between the epidemiological variables of the patients and the antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus strains was determined. Results: Staphylococcus spp. isolation was obtained in 8 samples, 62.5% of which were strains of the coagulase-positive Staphylococcus group, of which 25% were identified as Staphylococcus aureus and 37.5% as Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. The remaining 37.5% were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus strains, which were identified as Staphylococcus chromogenes (12.5%), Staphylococcus simulans (12.5%), and Staphylococcus lentus (12.5%). 50 % of the isolates were resistant, with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius being MDR, with resistance to 6 antibiotics, and S. lentus resistant to 5, both of which were also MRS. There was no association between the epidemiological variables of the patients and the antimicrobial susceptibility of the Staphylococcus strains. Conclusion: These preliminary results are the first report in Chile demonstrating the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus in a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South America using VITEK®. These results are relevant from a public health perspective given the close contact between owners, veterinarians, and dogs with otitis externa. These preliminary data contribute to the local understanding of this global phenomenon and provide information to support the theoretical framework for future local studies on epidemiological surveillance. Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Dog, otitis externa, Staphylococcus.. IntroductionCanine otitis externa is defined as inflammation of the external ear canal and is a common clinical disorder of complex multifactorial etiology affecting 10%–20% of canines (Scott et al., 2001; O’Neil et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). The most common primary causes are allergic-based pathologies, such as atopic dermatitis, food allergy (Griffin and DeBoer, 2001), and endocrine diseases, such as hypothyroidism (Rosser, 2004). These factors together with predisposing factors generate a microenvironment that favors the proliferation of secondary organisms such as yeasts and bacteria in the external ear canal (Rosser 2004, Kwon et al., 2025). Of the latter, species of the genus Staphylococcus are recognized as important bacteria of the skin and mucous membranes, including the outer ear (Zamankhan-Malayeri et al., 2010; Know et al., 2025). Members of this genus Staphylococcus are classified as coagulase-positive Staphylococcus (CPS) and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS), and they are reported as the main causative agents of numerous infections in animals and human patients worldwide (Malik et al., 2005; Morris and Cole, 2023). A significant number of cases may evolve into chronic or recurrent otitis, which is much more difficult to resolve clinically. These continuous cycles of infection and inflammation lead to pathological changes in the ear. In addition to the above, the use of treatments with different families of antimicrobials, without the result of complementary laboratory tests such as susceptibility tests, by veterinarians allows the selection of antimicrobial-resistant strains (Galarce et al., 2021). Thus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. (MRS), generally associated with the mecA gene, are microorganisms resistant to antibiotics β-lactamic, carbapenems, and quinolones (Siddiqui and Koirala, 2020). Some of these antimicrobials are frequently administered in the veterinary medicine of companion animals, as pointed out by Galarce et al. (2021), where dogs could be carriers of MRS strains, which is a risk factor, affecting not only pet guardians but also veterinarians (De Martino et al., 2016). Susceptibility to Staphylococcus antimicrobials in canine otitis externa has not yet been studied in Talca, Chile (35°25ʹS, 71°39ʹW), a rural South American city characterized by a temperate Mediterranean climate, with an average rainfall of 475 and 29 mm in winter and summer, respectively, and an average temperature of 18.8° Celsius. (Thomson et al., 2022). The acquisition of these data will contribute to the local understanding of antimicrobial susceptibility in Staphylococcus strains in canine otitis externa, contributing to the understanding of a global phenomenon of interest to public health. The objective of this study was to determine the existence of antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus strains isolated from the external auditory canal of a group of dogs diagnosed with otitis externa in Talca, Chile. Material and MethodsInclusion criteriaTwenty canine patients of any breed and sex were included in this study and were referred to dermatological interconsultation at Dermatovet Veterinary Clinic, located in the city of Talca. The sampled patients had signs of otitis externa, such as inflammation of the external pinna, pruritus, erythema, scabs, ear discharge, and rancid odor (Cabañes, 2021), and they did not receive antibiotic therapy 2 weeks prior to study entry. Sample collectionPrior to obtaining the sample, the patient was analyzed and recorded important data such as: age, sex, race, reproductive status, hospital stay, and previous antibiotic treatment. A complete physical examination was then performed using fear-free management (Otto et al., 2021). All guardians of the selected patients provided informed consent. The sample was obtained from the affected external ear canal by rubbing it for 15 seconds with a sterile solution spoiled with Stuart medium labeled with the identification of each patient. These samples were transported at refrigeration temperature (4°C) within a period of no more than 24 hours, to be processed and analyzed in the MICROVET Veterinary Microbiology laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary and Livestock Sciences of the University of Chile. Isolation of Staphylococcus spp.The torula was incubated in a liquid pre-enrichment medium Trypticase Oxoid® Soy broth (Thermo Scientific™) for 24 hours at 37°C, after which 100 l were sown in Columbia Oxoid® Blood agar (Thermo Scientific™) and in Oxoid® Mannitol Salt agar (Thermo Scientific™) media that were incubated at 37°C for 24–48 hours. The plate growth was evaluated by verifying the shape, color, and purity status of the growth and by performing a gram stain. After verifying that the growth corresponded to gram-positive cocaceae, an identification test was performed using the VITEK®2 Compact system (bioMérieux, Marcy; Étoile, France) and the GN ID card. (Rosales et al., 2024). Antimicrobial susceptibility testThe MIC of all confirmed strains of Staphylococcus spp. was assessed using the automated VITEK®2 Compact system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) to quantify their phenotypic antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This analysis was performed using the AST GP 80 card following the manufacturer’s instructions and the clinical cut-off values established by the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2020). The AST GP 80 cards included the following groups of antibiotics: amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, benzylpenicillin, cephalotin, cefovecina, detection of cefoxitin, ceftiofur, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, nitrofurantoin, doxycycline, enrofloxacin, tetracycline, kanamycin, marbofloxacin, neomycin, oxacillin, inducible resistance to clindamycin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to characterize the percentage distribution of the isolated strains and their antimicrobial susceptibility. The association between the epidemiological variables of the patients and the antimicrobial susceptibility of the Staphylococcus strains was determined by means of the exact Fisher test, considering 95% confidence and a α error of 5% InfoStat (Di Rienzo et al., 2008). Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the southern macrozone of the Universidad Santo Tomás (code nº 129-21) and was conducted in dermatological interconsultations (Dermatovet Talca) with veterinary clinics in the city of Talca, Región del Maule, Chile dated: 01th september 2023. Results and DiscussionOf the 20 patients, strains were isolated in 40%, of which 62.5% were CPS and 37.5% were CoNS (Table 1). 50% of the strains were sensitive to benzylpenicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, cefovecina, clindamycin, gentamicin, doxycycline, enrofloxacin, tetracycline, nitrofurantoin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The species Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Staphylococcus chromogenes, and S. lentus were MRS (Table 2). 50% of the strains presented resistance to antimicrobials, evaluated by the minimum inhibitory concentration method. Of these last strains, one strain was resistant to two families of antimicrobials, one strain to five, and two were resistant to more than 6 families of antimicrobials (Table 3). Likewise, 25% of the strains presented resistance to Oxacillin MRS and Doxycycline and 37.5% to Erythromycin (Fig. 1). The epidemiological variables of the sampled patients are presented in Table 4, and no association with Staphylococcus isolation was observed. Table 1. Isolation and identification of Staphylococcus spp. from otitis external in dogs.

Table 2. Frequency of Staphylococcus spp. strains according to species and antimicrobial resistance.

Table 3. Minimum inhibitory concentration of resistant strains.

Fig. 1. Frequency of antimicrobial resistance of strains of Staphylococcus spp. (8) isolated from dogs with otitis externa. Table 4. Epidemiological variables of patients according to Staphylococcus isolation.

AMR is a global concern and is estimated to be the leading cause of death in humans in the near future (O’Neill, 2014). This problem is not only present in human and veterinary medicine, and it is one of the main causes of the emergence of AMR, the overuse of antimicrobials, and prolonged treatment (Da Silva et al., 2013; Jasovský et al., 2016; Rosales et al., 2024). Otitis externa is a common manifestation in dogs, and the diagnosis should be based on an otoscopic examination of the external ear canal and cytology. Otitis externa is usually treated empirically with topical antibiotics and anti-inflammatories (Bourély et al., 2019; Galarce et al., 2021). However, because of the emergence of AMR in recent decades according to the standards for the appropriate use of antimicrobials, the strains should be isolated and tested for susceptibility to antimicrobials, especially in patients with frequent otitis. In the results of the present study, there was no statistical association between the antimicrobial susceptibility of the strains and the epidemiological variables of the patients, similar to that obtained by Rosales et al. (2024). This differs from Hoesktra and Paulton (2002), who indicated that the age of the animal was associated with different patterns of antimicrobial resistance to enrofloxacin, cephalotin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline. In this study, the isolation of CoNS strains was lower than that of and although it is described that the pathogenic potential is more frequently associated with CPS strains, they have been identified as an important source of determinants of antibiotic resistance (Harrison et al., 2013). Thus, the transmission of resistant bacteria from pets to humans has been the subject of recent research, describing that dogs and cats could be reservoirs and vectors of transmission (Marqués et al., 2016; Walther et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2019; Gwenzi et al., 2021, through direct or indirect contact of the shared environment, as well as through contaminated food in the case of production animals (Da Silva et al., 2013; Dierikx et al., 2013). In this study, the phenomenon of multiresistance, defined as resistance to three or more different antimicrobial families (Sweeney et al., 2018), was observed in 50% of Straphylococcus strains isolated from the ear canal of dogs with otitis externa, 25% of which were resistant, and identified as Staphylococcus aureus and S. pseudintermedius, a lower result than that described by Muñoz et al. (2012), where he obtained 30.2% of multidrug-resistant CPS strains, which can be attributed to larger sample size. In addition to skin and ears in animals, S. pseudintermedius can also be isolated from humans, and this would be due to the close contact of guardians with their dogs, which is why this species is considered an important zoonotic pathogen (Soedamanto et al., 2011; Robb et al., 2017). In addition to this transmission, drug-resistance genes carried by these strains can be exchanged with other Staphylococcus in humans (Robb et al., 2017). This risk of horizontal gene transfer between dog strains and those present in their guardians could induce more multidrug-resistant bacteria in the future, eventually making it more difficult to treat drug infections in humans (Lai et al., 2022). The strains analyzed had the highest resistance to clindamycin, followed by doxycycline and oxacillin. The latter is a marker of MRS. Resistance may occur due to the various empirical therapeutic uses of these antibiotics in companion animal clinics, such as in upper respiratory tract infections and dermatopathies (Hill et al., 2006). This situation has been reported in our country by Galarce et al. (2021), who described that only 15% of veterinarians use laboratory diagnostic tests, so the prescription of antimicrobials is carried out empirically. The strains of Staphylococcus spp. isolates showed a resistance of 25% to methicillin, which does not resemble what was described by other authors, such as De Martino et al. (2016), which reported 8.9% resistance, and Griffeth et al. (2008), which reported 4.2% resistance. In Chile, however, Muñoz et al. (2012) did not obtain resistant oxacillin strains, so the strains could be significantly changing their susceptibility patterns, and a likely cause could be the inappropriate use of this antibiotic over time in clinical practice. One CoNS strain, S. chromogenes, showed positive cefoxitin detection. This is a marker of the presence of the mecA gene, since it is a more potent inducer compound of the mecA regulatory system than penicillins. Therefore, by improving the expression of this gene, the detection of methicillin resistance is also improved. The use of the cefoxitin disc in the laboratory is especially useful and preferential over the oxacillin disc for detecting resistance to oxacillin mediated by the mecA gene in heteroresistant strains and should always be used in CoNS strains. In addition, this disc does not present stability problems like oxacillin during its conservation. There are strains with heteroresistance that usually appear as sensitive to many beta-lactamics when an antibiogram with discs is performed, and their interpretation as such can lead to therapeutic failures. Therefore, cefoxitin-resistant strains (≤8 mg/l and ≤24 mm CoNS) indicate the presence of mecA and, consequently, these strains are resistant to all beta-lactamics, so these antimicrobials should not be used in treatment (Swenson and Tenover, 2005; Reygaert, 2009; CLSI, 2011). The resistance results obtained in this study (12.5%) were similar to those reported by Bourely et al. (2019). Another CoNS strain, identified South lentus, in addition to the detection of cefoxitin, showed inducible resistance to clindamycin. This resistance to macrolide antibiotics in CoNS strains may be due to the msrA-encoded active efflux mechanism (which confers resistance only to macrolides and type B streptogramins) or to a ribosomal modification, affecting macrolides, lincosamides, and type B streptogramin (MLSB resistance) (Becker et al., 2020). Unfortunately, this resistance cannot be detected using traditional susceptibility methods, and the risk of not identifying this type of strain can lead to therapeutic failures with clindamycin in the clinical setting (De Oliveira et al., 2016). The resistance of the strains to doxycycline (25%) was lower than that described by Muñoz et al. (2012) in Chile, similar to that obtained by De Martino et al. (2016) in Italy, and greater than Bean and Wigmore (2016) in Australia, with 19.7% of resistant strains. These differences may be related to the prescribing habits of veterinarians, with doxycyclin being frequently prescribed in some countries (Watson and Madison, 2001). The use of doxycycline to treat other infections is common and may enable selection pressure that fosters emerging resistance in S. pseudintermedius strains. In addition, with the appearance of MRSP, veterinarians are increasingly forced to consider drugs that are not traditionally used on the skin. The lipophilic nature of doxycycline makes it a suitable alternative to β-lactamics for the treatment of MRSP infections when reported in susceptibility testing. Prudent use of antibiotics in the treatment of companion animals with skin infections can reduce the selection of MRSP and other multidrug-resistant bacteria that are important for animal and human health (Bean and Wigmore, 2016). The resistance of the strains to erythromycin of the species Staphylococcus lentus was lower than that reported by De Martino et al. (2016) and greater than that reported by Hariharan et al. (2006), with 5% resistance to Staphylococcus intermedius strains, which is well below the results obtained in this study. Song et al. (2013) described that the microbiota of the skin of humans and their pets is more similar to each other, compared to humans without pets, so there would be a transfer of microbiota from the guardian to the pet and vice versa. For this reason, due to the close contact between pets and their guardians, the transmission of resistant bacteria between them is possible, especially if it is estimated that pets are recipients of 37% of antibiotics intended for animals worldwide according to the World Organization for Animal Health report (2020), on the use of antimicrobials in animals. ConclusionThese preliminary results constitute the first report in Chile demonstrating the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus using BITEK® in a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South America, a region characterized by a Mediterranean climate. These results should be interpreted in a local context and extrapolated to the general population. However, this information is relevant from a public health perspective, given the close contact between owners, veterinarians, and dogs with otitis externa. These preliminary data contribute to the local understanding of this global phenomenon and provide information that supports the theoretical framework for future local epidemiological surveillance studies. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Author contributionsAndrea Núñez: Conception and design of the study, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript. Lisette Lapierre: First draft of the manuscript and methodology. Beatriz Escobar: writing the first draft of the manuscript and methodology. Rodrigo Castro: Writing one of the topics, stadistical methodology and critically revising the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the publication of the finale version of the manuscript. FundingThis research received no specific grant. ReferencesBean, D. and Wigmore, S. 2016. Carriage rate and antibiotic susceptibility of coagulase-positive staphylococci isolated from healthy dogs in Victoria, Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 94, 456–460 Becker, K., Both, A., Weißelberg, S., Heilmann, C. and Rohde, H. 2020. “Emergence of coagulase-negative staphylococci.” Expert Rev. Anti-infect. Ther. 18, 349–366. Bourély, C., Cazeau, G., Jarrige, N., Leblond, A., Madec, J., Haenni, M. and Gay, E. 2019. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from dogs with otitis. Epidemiol. Infect. 147, e121. Cabañes, F.2021. Diagnosis of Malassezia dermatitis and otitis in dogs and cats, is it just a matter of telling? Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 38, 3–4. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty first informational supplement. 2011. Document M100-S21. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, vol. 31, pp: 163. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for Bacteria isolated from animals, 5th edition. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, vol. 40, pp: 215. Da Silva, K., Knobel, T. and Moreno, A. 2013. Antimicrobial resistance in veterinary medicine: mechanisms and bacterial agents with the greatest impact on human health. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 50, 171–183. De Martino, L., Nocera, F., Mallardo, K., Nizza, S., Masturzo, E., Fiorito, F., Iovane, G. and Catalanotti, P. 2016. An update on microbiological causes of Canine Otitis externa in Campania Region, Italy. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 6, 384–389. De Oliveira, A., Cataneli Pereira, V., Pinheiro, L., MoraesRiboli, D., Benini Martins, K., Da Cunha, R. and De Lourdes, M. 2016. “Antimicrobial resistance profile of planktonic and biofilm cells of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci”. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17, 1423. Di Rienzo, J., Cassanoves, F., Balzarini, M., González, L., Tablada, M. and Robledo, C. 2008. InfoStat. Córdoba, Argentina: National University of Córdoba. Dierikx, C., Van der Goot, J., Fabri, Y., Van Essen-Zandbergen, A., Smith, H. and Mevius, D. 2013. Extended-spectrum-b-lactamase- and AmpC-blactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Dutch broilers and broiler farmers. J Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 60–67. Galarce, N., Arriagada, G., Sánchez, F., Venegas, W., Cornejo, J. and Lapierre, L. 2021. Antimicrobial use in companion animals: assessing veterinarians prescription patterns through the first National Survey in Chile. Animals. 11, 348. Griffeth, G., Morris, D., Abraham, J., Shofer, F. and Rankin, S. 2008. Screening for skin carriage of methicillin-resistant coagulase-positive staphylococci and Staphylococcus schleiferi in dogs with healthy and inflamed skin. Vet. Dermatol. 19, 142–149. Griffin, C. and Deboer, D. 2001. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XIV): clinical manifestations of canine atopic dermatitis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 81, 255–269. Gwenzi, W., Chaukura, N., Muisa-Zikali, N., Teta, C., Musvuugwa, T., Rzymski, P. and Abia, A. 2021. Insects, rodents, and pets as reservoirs, vectors, and sentinels of antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics (Basel). 10, 68. Hariharan, H., Coles, M., Poole, D., Lund, L. and Page, R. 2006. Update on antimicrobial susceptibilities of bacterial isolates from canine and feline otitis externa. Can. Vet. J. 47, 253–255. Harrison, E., Paterson, G., Holden, M., Morgan, F., Larsen, A., Petersen, A., Leroy, S., Vliegher, S., Perretten, V. and Fox, L. 2013. A Staphyloccocus xylosus isolate with a new mecC allotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 1524–1528. Hill, P., Lo, A., Eden, C., Huntley, S., Morey, V., Ramsey, S., Richardson, C., Smith, D., Sutton M., Taylor E., Thorpe, R., Tidmarsh, V. and Williams, V. 2006. Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice. Vet. Rec. 158, 533–539. Hoekstra, K. and Paulton, R. 2002. Clinical prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus and Staph. intermedius in dogs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93, 406–413. Hong, J., Song, W., Park, H., Oh, J., Chae, J., Shin, S. and Jeong, H. 2019. Clonal spread of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- resistant Enterobacteriaceae between companion animals and humans in South Korea. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1371. Jasovský, D., Littmann, J., Zorzet, A. and Cars, O. 2016. Antimicrobial resistance—a threat to the world’s sustainable development. UJMS. 121, 159–164. Kwon, J., Kim, S., Kim, S., Kim, H., Kang, J., Jo, S., Giri, S., Jeong, W., Lee, S., Kim, J. and Park, S. 2025. Tailoring formulation for enhanced phage therapy in canine otitis externa: a cocktail approach targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Vet. Microbiol. 301, 110354. Lai, C., M, Y., Shia, W., Hsieh, Y. and Wang, C. 2022. Risk factors for antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus species isolated from dogs with superficial pyoderma and their owners. Vet. Sci. 9, 306. Li, J., Li, L., T, F. and Lu, D. 2023. The epidemiology of canine ear diseases in Northwest China: analysis of data on 221 dogs from 2012 to 2016. Vet. World. 16, 2382–2388. Malik, S., Peng, H. and Barton, M. 2005. Antibiotic resistance in staphylococci associated with cats and dogs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99, 1283–1293. Marqués, C., Gama, L., Belas, A., Bergström, K., Beurlet, S., Briend-Marchal, A., Broens, E., Costa, M., Criel, D., Damborg, P., Van Dijk, M., Van Dongen, A., Dorsch, R., Espada, C., Gerber, B., Kritsepi-Konstantinou, M., Loncaric, I., Mion, D., Misic, D., Movill, R., Overesch, G., Perreten, V., Roura, X., Steenbergen, J., Timofte, D., Wolf, G., Zanoni, RG., Schmitt, S., Guardabassi, L. and Pomba, C. 2016. European multicenter study on antimicrobial resistance in bacteria isolated from companion animal urinary tract infections. BMC Vet. Res. 12, 213. Morris, D. and Cole, S., 2023. The epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance and transmission of cutaneous bacterial pathogens in domestic animals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 261, S122–S129. Muñoz, L., Molina, M., Heresmann, M., Abusleme, F., Ulloa, M., Borie, C., San Martin, B., Silva, V. and Anticevic, S. 2012. Primer reporte de aislamiento de Staphylococcus schleiferi subespecie coagulans en perros con pioderma y otitis externa en Chile. Arch. Med. Vet. 44, 261–265. O’Neill, J. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev. Antimicrob. Resistance. 1, 1–20. O’Neill, D., Volk, A., Soares, T., Church, D., Brodbelt, D. and Pegram, C. 2021. Frequency and predisposing factors for canine otitis externa in the UK–a primary veterinary care epidemiological view. Canine Med. Genet. 8, 7. Otto, C., Cohen, J., Darling, T., Murphy, L., Ng, Z., Pierce, B., Singletary, M. and Zoran, D. 2021 AAHA working, assistance, and therapy dog guidelines. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 57, 253–277. Reygaert, W. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): identification and susceptibility testing techniques. Clin. Lab. Sci. 22, 120–124. Robb, A., Wright, E., Foster, A., Walker, R. and Malone, C. 2017. Skin infection caused by a novel strain of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in a Siberian husky dog owner. JMM Case Rep. 4, jmmcr005087. Rosales, R., Ramírez, A., Moya-Gil, E., De la Fuente, S., Suárez-Pérez, A. and Poveda, J. 2024. Microbiological survey and evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of microorganisms obtained from suspect cases of Canine Otitis externa in Gran Canaria, Spain. Animals. 14, 742. Rosser, E. 2004. Causes of otitis externa. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 34, 459–468. Scott, D., Miller Jr, W. and Griffin, C. 2001. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 6th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. Siddiqui A. and Koirala J. 2020. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Soedarmanto, I., Kanbar, T., Ulbegi-Mohyla, H., Hijazin, M., Alber, J., Lammler, C., Akineden, O., Weiss, R., Moritz, A. and Zschock, M. 2011. Genetic relatedness of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) isolated from a dog and the dog owner. Res. Vet. Sci. 91, e25–e27. Song, S., Lauber, C., Costello, E., Lozupone, C., Humphrey, G., Berg-Lyons, D., Caporaso, J., Knights, D., Clemente, J., Nakielny, S., Gordon, J., Fierer, N. and Knight, R. 2013. Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. eLife 2, e00458. Sweeney, M., Lubbers, B., Schwarz, S. and Watts, J. 2018. Applying definitions for multidrug resistance, extensive drug resistance and pandrug resistance to clinically significant livestock and companion animal bacterial pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1460–1463. Swenson, J. and Tenover, F. 2005. Cefoxitin disk Study Group. Results of disk diffusion testing with cefoxitin correlate with presence of mecA in Staphylococcus spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 3818–3823. Thomson, P., Pareja, J., Núñez, A., Santibáñez, R. and Castro, R. 2022. Characterization of microbial communities and predicted metabolic pathways in the uterus of healthy mares. Open Vet. J. 12, 797–805. Walther, B., Tedin, K. and Lübke-Becker, A. 2017. Multidrug-resistant opportunistic pathogens challenging veterinary infection control. Vet. Microbiol. 200, 71–78. Watson, A. and Maddison, J. 2001. Systemic antibacterial drug use in dogs in Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 79, 740–746. World Organisation for Animal Health. 2020. OIE Annual Report on Antimicrobial Agents for Use in Animals. Paris, France: World organisation for animal health, p 132. Zamankhan Malayeri, H., Jamshidi, S. and Salehi, T. 2010. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria causing otitis externa in dogs. Vet. Res. Commun. 34, 435–444. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Núñez A, Lapierre L, Escobar B, Castro R. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 Web Style Núñez A, Lapierre L, Escobar B, Castro R. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=243875 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Núñez A, Lapierre L, Escobar B, Castro R. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Núñez A, Lapierre L, Escobar B, Castro R. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 Harvard Style Núñez, A., Lapierre, . L., Escobar, . B. & Castro, . R. (2025) Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 Turabian Style Núñez, Andrea, Lisette Lapierre, Beatriz Escobar, and Rodrigo Castro. 2025. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 Chicago Style Núñez, Andrea, Lisette Lapierre, Beatriz Escobar, and Rodrigo Castro. "Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Núñez, Andrea, Lisette Lapierre, Beatriz Escobar, and Rodrigo Castro. "Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2895-2902. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Núñez, A., Lapierre, . L., Escobar, . B. & Castro, . R. (2025) Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus isolated from the ear canal of a group of dogs with otitis externa in Talca, Chile, South América Preliminary results. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2895-2902. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.59 |