| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3097-3103 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(7): 3097-3103 Research Article Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysisAhmad Al Athamneh1*, Anas Khaleel2, Leena Ahmad1, Rahaf Qaraqish1, Abed Elrahman Altaha3 and Hanaa Khalaf11Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Pharmacy and Medical Science, University of Petra, Amman, Jordan 2Department of Pharmacology and Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of Petra, Amman, Jordan 3Department of Slaughterhouses, Greater Amman Municipality, Amman, Jordan *Corresponding Author: Ahmad Al Athamneh, Department of Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Pharmacy and Medical Science, University of Petra, Amman, Jordan. Email: ahmad.alathamneh [at] uop.edu.jo Submitted: 07/03/2025 Revised: 14/06/2025 Accepted: 15/06/2025 Published: 31/07/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

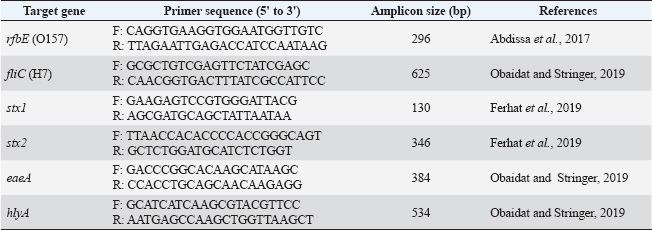

ABSTRACTBackground: The zoonotic pathogen Escherichia coli O157: H7, known as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), is a public health concern associated with acute gastrointestinal diseases and hemolytic uremic syndrome. The primary reservoirs of EHEC are ruminants, including cattle and, potentially, sheep. However, data on EHEC prevalence and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Jordanian sheep are scarce. Aim: This study aimed to examine the prevalence of EHEC and to assess antibacterial resistance patterns in non-EHEC E. coli isolates from Awasi sheep in Central Jordan. Methods: Rectal swabs from 198 sheep were collected and analyzed using conventional bacteriological methods and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for genotypic confirmation of EHEC. The sample size was calculated using an anticipated prevalence of 5%, a confidence level of 95%, and a precision of 3%. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the disc diffusion method for ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, and erythromycin, with findings interpreted according to standards. Results: None of the 198 EHEC isolates were identified among the 198 samples. However, 18 samples (9%) contained non-EHEC E. coli isolates, all of which exhibited resistance to at least one antibiotic. Notably, all isolates (100%) showed resistance to ampicillin, 94.4% to erythromycin, and 5.6% were ciprofloxacin-resistant. No significant variations in prevalence were found between sampling sites (p=0.78). Conclusion: The absence of EHEC in local sheep suggests that they are not a primary source of this pathogen in Jordan. However, the observed AMR in non-EHEC isolates highlights the need for stringent sanitary practices and antimicrobial stewardship to mitigate public health risks. Seasonal and age-related variations should be explored in future longitudinal studies. Keywords: E. coli O157:H7, Antimicrobial resistance, Zoonotic pathogens, Awasi sheep, Jordan. IntroductionFoodborne diseases caused by microbiological pathogens pose a critical threat to food safety and public health worldwide. Among these, Escherichia coli O157:H7, a strain of enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), is a major concern due to its potential to cause severe symptoms of gastrointestinal illness, including hemorrhagic colitis and other conditions, such as hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (Busani et al., 2005; Ferens and Hovde, 2011; Rahal et al., 2012). EHEC is primarily associated with ruminants, particularly cattle, which act as asymptomatic reservoirs for this zoonotic pathogen (Elder et al., 2000; Rahal et al., 2012). However, the role of sheep as potential carriers of EHEC is poorly understood, particularly in the Middle East region. The Awasi sheep breed is indigenous to Jordan and represents a substantial proportion of the country’s livestock industry. These sheep are commonly present in local markets and contribute significantly to the food supply chain. Despite this, no previous study has specifically assessed the prevalence of EHEC in live Awasi sheep in the Jordanian market. Given that sheep may act as vectors for zoonotic transmission, understanding their role in the epidemiology of EHEC is critical for public health monitoring and infection control strategies (Al-Barakeh et al., 2024). Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of E. coli isolates from livestock adds another layer of complexity to food safety concerns. Antibiotic overuse and misuse in animal husbandry contribute to the development of resistant strains of bacteria. These bacteria can be transmitted to humans via direct contact or consumption of contaminated products (Reid et al., 2002; Hajian et al., 2011). Studies in Jordan and neighboring regions have reported varying levels of antibiotic resistance in E. coli, underscoring the need for localized research to inform mitigation strategies (McCarthy et al., 2021). This study investigated the prevalence of EHEC in Awasi sheep in Central Jordan and evaluated the antibacterial susceptibility of non-EHEC E. coli isolates. The outcomes of this study will enhance our understanding of the role of sheep in EHEC transmission and the possible dangers associated with antibiotic resistance in the livestock industry. Materials and MethodsDetermination and collection of sample sizeThe sample size was determined using the formula n=Z²P(1−P)/d², where Z represents the Z statistic for a 95% confidence level (1.96), P denotes the anticipated prevalence (5% based on regional research), and d signifies the precision (3%). This yielded a minimum sample size of 196, which was rounded to 198. This sample size provides 80% power for detecting EHEC at the expected prevalence rate. A total of 198 male Awasi sheep, approximately 1.5 years old, were randomly selected from six sublocations within the Central Jordan livestock market. Thirty-three rectal swabs were collected per sublocation (n=198) during the first week of April 2024. While this sampling strategy focused on a specific demographic and period, it provided a cross-sectional snapshot of the target population. We acknowledge this as a limitation that affects our ability to generalize our findings to female sheep, different age groups, and seasonal variations. Samples were obtained using sterile cotton swabs, immediately placed in Stuart’s transport media (Oxoid, UK), and maintained under refrigerated conditions (4°C) until processing in the laboratory within 24 hours of collection. All collection procedures were performed using aseptic techniques, with field and laboratory personnel wearing appropriate personal protective equipment to minimize cross-contamination. EHEC isolation using the conventional methodIn each testing group, E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 43895) served as the positive control, whereas nontoxigenic E. coli (NCTC 12900) served as the negative control for bacterial isolation. Rectal swabs were immersed in 50 ml of Trypticase Soy Broth modified with Novobiocin (8 mg/l) (MTSB) (Condalab, Madrid, Spain) and incubated at 42°C for 24 hours (WTW TS 606-G 121, Germany). Following enrichment, 100 μl of broth was streaked onto Sorbitol MacConkey agar with cefixime (0.05 mg/l) and potassium tellurite (2.5 mg/l) (SMAC-CT) for selective isolation. The limit of detection for this method, based on internal validation and previous studies, is approximately 10² CFU/g. Non-sorbitol fermenting colonies, indicative of potential EHEC, appeared colorless on SMAC-CT agar, whereas sorbitol-metabolizing organisms formed pink colonies. All plates were examined by two independent laboratory technicians to minimize observer bias. The suspected EHEC isolates were further processed for genotypic confirmation using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Obaidat and Stringer, 2019). Genotypic identification and characterization of pathogenic EHEC strainsDNA was extracted from fresh bacterial growth samples and reference strains using a Biotecon negative gram extraction kit (Manchester, UK) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality control measures included blank extraction controls that were applied alongside the samples to monitor for potential contamination. Genotypic identification of E. coli O157:H7 was conducted using PCR, targeting specific serotypes and virulence genes. The presence of O157 and H7 serotypes was confirmed by amplifying the rfbE (O157) and fliC (H7) genes, respectively. Additionally, PCR assays were performed to detect virulence genes, including stx1, stx2 (Shiga toxins 1 and 2), eaeA (intimin), and hlyA (hemolysin). Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was conducted using a Bio-Rad CFX96 system (California, USA) with a Biotecon O157:H7 kit (Potsdam, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Each PCR run included positive and negative controls, and samples were tested in duplicate to ensure reproducibility. The analytical sensitivity of the PCR assay, as reported by the manufacturer, was 10 genomic copies per reaction. The primer sequences used for gene amplification are detailed in Table 1. Although the PCR assay used in this study is reported by the manufacturer to have high analytical sensitivity (10 genomic copies per reaction), we did not perform a full diagnostic validation involving the calculation of sensitivity, specificity, or predictive values due to the absence of positive EHEC cases. Antimicrobial susceptibilityAntimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the isolated E. coli strains and reference E. coli strain O157:H7 (ATCC 43895). Bacterial cultures were grown on trypticase soybean agar supplemented with 0.6% yeast extract. Active cultures were prepared by inoculating isolates in 10 ml of Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) (Oxoid) and incubating at 37 °C for 18–24 hours. Bacterial concentrations were standardized to 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1.5 × 10^8^ CFU/ml) by comparing turbidity with the McFarland standard solution. Antimicrobial susceptibility was assessed using the disk diffusion method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (2023). Mueller–Hinton agar plates were inoculated with standardized bacterial suspensions, and antibiotic disks were placed on the surface. Table 1. Primers for O157H7 genes used in PCR.

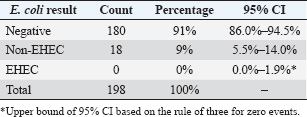

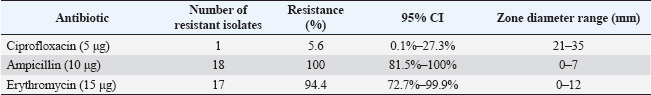

The selected antibiotics were ciprofloxacin (5 μg/disc), Ampicillin (10 μg/disc), and Erythromycin (15 μg/disc) (HiMedia, India). These antibiotics were selected based on their common use in veterinary and human medicine in Jordan and their clinical relevance (Abdissa et al., 2017; Ferhat et al., 2019). After 18–24 hours of incubation at 37°C, zone diameters were measured and interpreted according to CLSI breakpoints. The quality control strain E. coli ATCC 25922 was included in each batch of testing to validate the results. All tests were performed in duplicate to ensure reproducibility. Statistical analysisData analysis was conducted employing IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The prevalence of E. coli isolates was determined as the ratio of positive samples to the total number examined, expressed as a percentage. Chi-square tests were used to compare prevalence rates across various sublocations, with a p-value of <0.05 deemed statistically significant. Resistance rates for antimicrobial susceptibility data were determined as the percentage of isolates exhibiting resistance to each drug. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine variations in resistance patterns across sampling locations. Confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed for all prevalence and resistance estimations to evaluate precision. Ethical approvalThis work received ethical approval from the University of Petra’s Ethical Committee (Approval number: E/A/11/3/2024). ResultsOf the 198 rectal swab samples collected, none showed EHEC characteristics on CT-SMAC agar or tested positive for EHEC-specific genes by PCR. Eighteen samples (9%; 95% CI: 5.5%–14.0%) yielded non-EHEC E. coli isolates, whereas 180 samples (91%; 95% CI: 86.0%–94.5%) were negative for E. coli presence (Table 2). The distribution of non-EHEC E. coli across the six sampling sublocation was relatively uniform, with no statistically significant differences (χ²=2.47, df=5, p=0.78). The prevalence ranged from 6.1% (2/33) to 12.1% (4/33) across sublocations. Molecular conformation analysis using PCRAll 18 non-EHEC E. coli isolates were subjected to PCR to confirm the absence of EHEC-specific serotypes (rfbE, fliC) and virulence genes (stx1, stx2, eaeA, and hlyA). Consistent with the phenotypic results, all samples tested negative for these markers, confirming the absence of EHEC. The positive controls consistently showed appropriate amplification of all target genes, whereas the negative controls showed no amplification. Antimicrobial susceptibility patternsAntimicrobial susceptibility testing of 18 non-EHEC E. coli isolates revealed varied resistance profiles. All isolates (100%; 95% CI: 81.5%–100%) demonstrated resistance to Ampicillin. Resistance to Erythromycin was observed in 17 isolates (94.4%; 95% CI: 72.7%–99.9%), whereas only one isolate (5.6%; 95% CI: 0.1%–27.3%) showed resistance to Ciprofloxacin (Table 3). DiscussionPrevalence of EHEC in Jordanian sheepThe absence of EHECs in the 198 rectal swab samples from Awasi sheep in Central Jordan is a notable contrast to studies in other regions. Based on our sample size, we can state with a 95% confidence interval that the true prevalence of EHEC in this population is less than 1.9% (using the rule of three for zero events). This finding is consistent with several regional studies but differs from reports in other countries. In neighboring countries, varying prevalence rates of this disease have been reported. A study in Egypt found EHEC in 2.2% of sheep (Kamel et al., 2015). Studies from Europe have shown prevalence rates ranging from 5% in Spain (Blanco et al., 2003) to 7.4% in Ireland (McCarthy et al., 2021). In contrast, higher rates have been observed in developing countries, with studies reporting prevalence rates of 6.1% in Ethiopia (Abreham et al., 2019) and 12.6% in Pakistan (Shahzad et al., 2021). This geographical variation may be attributed to differences in husbandry practices, environmental factors, and detection methodologies. Reported EHEC prevalence rates vary widely across studies due to methodological diversity. Differences in sample type, enrichment protocols, PCR assays, and diagnostic thresholds significantly affect detection outcomes. Standardizing methodology and validation practices is crucial for reliable interstudy comparisons (WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2023). Unlike cattle, which are established primary reservoirs of EHEC, sheep may have a lower colonization rate or a different interaction with the pathogen, potentially limiting EHEC transmission (Askari and Ghanbarpour, 2019; Obaidat, 2020). The molecular confirmation using PCR reinforced the absence of EHEC-specific serotypes and virulence genes, thus validating our conventional isolation methods. Table 2. Distribution of E.coli O157H7 and Non-O157H7 among 198 sheep rectal swab samples.

Several factors may have contributed to our findings: The arid climate of Jordan may not favor the persistence of EHEC in the environment. Additionally, the timing of our sampling in April may have limited our ability to capture potential seasonal peaks in EHEC shedding, as some studies suggest higher shedding rates during warmer months (Edrington et al., 2006). Furthermore, our study’s focus on 1.5-year-old sheep may have influenced the results, given that previous research indicates a higher prevalence of EHEC in younger animals. Traditional sheep management practices in Jordan, which often involve extensive grazing in arid regions, may also contribute to lower EHEC transmission rates. Unlike feedlot conditions, these practices typically involve less intensive animal contact, potentially reducing the risk of pathogen spread(Zhang et al., 2024). Although our detection methods adhere to international standards, with a detection limit of approximately 10² CFU/g, methodological challenges remain (De Boer and Heuvelink, 2000). The isolation of EHECs can be particularly difficult because of the presence of competing microflora and potentially low concentrations of the pathogen in samples (De Boer and Heuvelink, 2000). AMR in non-EHEC E. coliDespite the absence of EHEC, the detection of non-EHEC E. coli isolates with resistance to multiple antibiotics represents a significant public health concern. The high resistance rates to Ampicillin (100%) and Erythromycin (94.4%) observed in our study parallel findings from other regional studies. Obaidat et al. (2019) reported 85.7% resistance to Ampicillin in E. coli isolates from Jordanian cattle, whereas Osaili et al. (2013) found 92.3% resistance to Ampicillin in beef cattle isolates (Osaili et al., 2013; Obaidat, 2020). The low resistance to Ciprofloxacin (5.6%) is encouraging and consistent with studies showing lower resistance rates to fluoroquinolones in livestock-associated E. coli (Obaidat, 2020). This may reflect the more restricted use of this class of antibiotics in Jordanian livestock production compared with beta-lactams and macrolides. The observed resistance patterns raise several concerns regarding antibiotic use and public health implications. High resistance rates likely reflect selection pressure arising from antibiotic use in the animal industry. In Jordan, antibiotics are often available without prescription for veterinary use, which may contribute to the development of resistance(Abou-Jaoudeh et al., 2024). Furthermore, commensal E. coli may serve as a reservoir for resistance genes that can be disseminated to dangerous bacteria via horizontal gene transfer pathways. This process amplifies public health risks by facilitating the spread of antibiotic resistance within microbial communities (Leclercq et al., 2024). Additionally, resistant bacteria from livestock can enter the food chain during slaughter and processing, potentially exposing consumers to resistant organisms and posing a direct threat to food safety (Almansour et al., 2023). Public health implicationsThis study’s findings include significant public health implications, particularly pertinent to the Jordanian context. While sheep may not serve as significant reservoirs for EHEC in Jordan, the presence of antibiotic-resistant commensal E. coli underscores the necessity of stringent hygiene measures during slaughter and processing to minimize the risk of meat product contamination. The study’s results also highlight the need for improved antimicrobial stewardship in Jordanian livestock production. Although Jordan has established a National Action Plan on AMR (2018–2022), challenges remain, especially within the agricultural sector, where implementation is often difficult (WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2023). Additionally, the absence of EHEC in this study does not negate the importance of continued surveillance. Given the dynamic nature of bacterial populations and potential for emerging resistance, sustained monitoring is crucial. Addressing AMR effectively requires a One Health approach that fosters coordination between the veterinary, agricultural, and public health sectors. In a resource-limited setting like Jordan, preventing the transmission of resistant bacteria from animals to humans is particularly vital for safeguarding public health. Table 3. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Non-O157:H7 E. coli Isolates.

Limitations and future researchThis study has some limitations. The study’s cross-sectional approach merely provides a snapshot at one time point, restricting the capacity to detect temporal fluctuations in EHEC shedding and resistance patterns. Longitudinal studies are more effective for understanding these temporal dynamics. Additionally, the study’s demographic focus on male Awasi sheep of a specific age restricted the generalizability of the results to a broader sheep population. Including a more diverse sample with different age groups, sexes, and various breeds in future studies would enhance the robustness of the findings. The geographical scope of the study, which was limited to Central Jordan, may not accurately represent conditions across other regions of the country. Conducting a comprehensive national survey would provide a complete picture of EHEC prevalence and resistance patterns. The exclusion of cephalosporins and tetracyclines from our antimicrobial susceptibility testing was a limitation driven by resource constraints and methodological scope. Including these classes would require additional funding, time, and technical capacity beyond the current study design. Future studies should consider expanding the antibiotic panel to provide a comprehensive resistance profile. Lastly, although the study confirmed the absence of EHECs, the molecular characterization of non-EHEC isolates was limited. Incorporating more advanced techniques, such as sequence-based typing and the identification of resistance genes, would yield deeper insights into the bacterial population structure and underlying resistance mechanisms. Future research should explore several key directions to build on the findings of this study. Investigating seasonal variations in EHEC prevalence through year-round sampling will provide valuable insights into potential temporal trends in shedding and resistance patterns. Additionally, examining the entire food chain from farm to fork could help identify critical points of contamination and inform targeted interventions. Conducting molecular analyses of resistance determinants in commensal E. coli would enhance our understanding of the mechanisms underlying resistance and their potential transferability to pathogenic bacteria. Furthermore, comparing resistance patterns between livestock and human isolates would be instrumental in assessing potential transmission pathways and associated public health impacts. Evaluating the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing antibiotic use in livestock production will also contribute to developing evidence-based strategies to mitigate AMR risks in Jordan and beyond. ConclusionThis study found no E. coli O157:H7, a strain of (EHEC) in Awasi sheep in Central Jordan, suggesting that these sheep are unlikely to be a significant EHEC reservoir. However, the detection of non-EHEC E. coli isolates with high resistance to Ampicillin (100%) and Erythromycin (94.4%) raises concerns about AMR in livestock. The absence of EHEC contrasts with studies from other regions, highlighting the importance of local epidemiological investigations. Various factors may have contributed to this finding, including regional husbandry practices, environmental conditions, and potential seasonal variations not captured in our cross-sectional design. The AMR observed in commensal E. coli isolates underscores the need for prudent antibiotic use in Jordan’s livestock sector. These resistant bacteria can enter the food chain and contribute to the broader issue of AMR, representing a significant public health challenge. Our findings emphasize the importance of

Future research should expand the sampling scope temporally and geographically, explore the molecular mechanisms of resistance, and investigate potential interventions to mitigate AMR in Jordan’s livestock industry. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to acknowledge the efforts of the University of Petra’s Faculty of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, its dean, and its Department Head of Pharmacology and Biomedical Sciences. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies. FundingThis study was not funded. Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to this study. Ahmad Al Athamneh conceptualized the study, coordinated the research activities, and led the manuscript preparation. Anas Khaleel performed the antibiotic sensitivity analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the results. Leena Ahmad, Rahaf Qaraqish, and Hanaa Khalaf participated in data collection, laboratory analysis, and data entry. Abed Elrahman Altaha facilitated sample collection from slaughterhouses and provided logistical support. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study. No financial, personal, or professional affiliations influenced the research, analysis, or presentation of the findings. Data availabilityThe data generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr Ahmad Al Athamneh, upon reasonable request. ReferencesAbdissa, R., Haile, W., Fite, A.T., Beyi, A.F., Agga, G.E., Edao, B.M., Tadesse, F., Korsa, M.G., Beyene, T., Beyene, T.J., De Zutter, L., Cox, E. and Goddeeris, B.M. 2017. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in beef cattle at slaughter and beef carcasses at retail shops in Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 17(1), 277. Abou-Jaoudeh, C., Andary, J. and Abou-Khalil, R. 2024. Antibiotic residues in poultry products and bacterial resistance: a review in developing countries. J. Infect. Public Health 17(12), 102592. Abreham, S., Teklu, A., Cox, E. and Sisay Tessema, T. 2019. Escherichia coli O157:H7: distribution, molecular characterization, antimicrobial resistance patterns and source of contamination of sheep and goat carcasses at an export abattoir, Mojdo, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 19(1), 215. Al-Barakeh, F., Khashroum, A.O., Tarawneh, R.A., Al-Lataifeh, F.A., Al-Yacoub, A.N., Dayoub, M. and Al-Najjar, K. 2024. Sustainable sheep and goat farming in arid regions of Jordan. Ruminants 4(2), 241–255. Almansour, A.M., Alhadlaq, M.A., Alzahrani, K.O., Mukhtar, L.E., Alharbi, A.L. and Alajel, S.M. 2023. The silent threat: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in food-producing animals and their impact on public health. Microorganisms 11(9), 2127.. Askari, N. and Ghanbarpour, R. 2019. Molecular investigation of the colicinogenic Escherichia coli strains that are capable of inhibiting E. coli O157:H7 in vitro. BMC Vet. Res. 15(1), 14. Blanco, J., Blanco, M., Blanco, J.E., Mora, A., González, E.A., Bernárdez, M.I., Alonso, M.P., Coira, A., Rodriguez, A., Rey, J., Alonso, J.M. and Usera, M.A. 2003. Verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in Spain: prevalence, serotypes, and virulence genes of O157:H7 and non-O157 VTEC in ruminants, raw beef products, and humans. Exp. Biol. Med. 228(4), 345–351. Busani, L., Cigliano, A., Taioli, E., Caligiuri, V., Chiavacci, L., Di Bella, C., Battisti, A., Duranti, A., Gianfranceschi, M., Nardella, M.C., Ricci, A., Rolesu, S., Tamba, M., Marabelli, R. and Caprioli, A. 2005. Prevalence of Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes contamination in foods of animal origin in Italy. J. Food Prot. 68(8), 1729–1733. De Boer, E. and Heuvelink, A.E. 2000. Methods for the detection and isolation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. (29), 133S–143S. Edrington, T.S., Callaway, T.R., Ives, S.E., Engler, M.J., Looper, M.L., Anderson, R.C. and Nisbet, D.J. 2006. Seasonal shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ruminants: a new hypothesis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3(4), 413–421. Elder, R.O., Keen, J.E., Siragusa, G.R., Barkocy-Gallagher, G.A., Koohmaraie, M. and Laegreid, W.W. 2000. Correlation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 prevalence in feces, hides, and carcasses of beef cattle during processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97(7), 2999–3003. Ferens, W.A. and Hovde, C.J. 2011. Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8(4), 465–487. Ferhat, L., Chahed, A., Hamrouche, S., Korichi-Ouar, M. and Hamdi, T.-M. 2019. Research and molecular characteristic of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from sheep carcasses. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 68(6), 546–552. Hajian, S., Rahimi, E. and Mommtaz, H. 2011. A 3-year study of *Escherichia coli* O157:H7 in cattle, camel, sheep, goat, chicken and beef minced meat. Proc. Int. Conf. Food Eng. Biotechnol. 9, 163–165. Kamel, M., Abo El-Hassan, D.G. and El-Sayed, A. 2015. Epidemiological studies on Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Egyptian sheep. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 47(6), 1161–1167. Leclercq, S.O., Bochereau, P., Foubert, I., Baumard, Y., Travel, A., Doublet, B. and Baucheron, S. 2024. Persistence of commensal multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in the broiler production pyramid is best explained by strain recirculation from the rearing environment. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1324972. McCarthy, S.C., Macori, G., Duggan, G., Burgess, C.M., Fanning, S. and Duffy, G. 2021. Prevalence and whole-genome sequence-based analysis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from the recto-anal junction of slaughter-age Irish sheep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87(24), e0138421. Obaidat, M.M. 2020. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in imported beef cattle in Jordan. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70, 101447. Obaidat, M.M. and Stringer, A.P. 2019. Prevalence, molecular characterization, and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, and Escherichia coli O157:H7 on dairy cattle farms in Jordan. J. Dairy Sci. 102(10), 8710–8720. Osaili, T.M., Alaboudi, A.R. and Rahahlah, M. 2013. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on beef cattle slaughtered in Amman abattoir. Meat Sci. 93(3), 463–468. Rahal, E.A., Kazzi, N., Nassar, F.J. and Matar, G.M. 2012. Escherichia coli O157:H7–Clinical aspects and novel treatment approaches. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 138. Reid, C.-A., Small, A., Avery, S.M. and Buncic, S. 2002. Presence of food-borne pathogens on cattle hides. Food Control 13(6), 411–415. Shahzad, A., Ullah, F., Irshad, H., Ahmed, S., Shakeela, Q. and Mian, A.H. 2021. Molecular detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157 in sheep, goats, cows and buffaloes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48(8), 6113–6121. WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. 2023. Jordan’s national action plan on antimicrobial resistance launches under royal patronage. Geneva: WHO. Available via https://www.emro.who.int/jor/jordan-news/jordans-national-action-plan-on-antimicrobial-resistance-launches-under-royal-patronage.html (Accessed 12 June 2025). Zhang, T., Nickerson, R., Zhang, W., Peng, X., Shang, Y., Zhou, Y., Luo, Q., Wen, G. and Cheng, Z. 2024. The impacts of animal agriculture on One Health—Bacterial zoonosis, antimicrobial resistance, and beyond. One Health 18, 100748. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Athamneh AA, Khaleel A, Ahmad L, Qaraqish R, Altaha AE, Khalaf H. Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 Web Style Athamneh AA, Khaleel A, Ahmad L, Qaraqish R, Altaha AE, Khalaf H. Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=246388 [Access: January 12, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Athamneh AA, Khaleel A, Ahmad L, Qaraqish R, Altaha AE, Khalaf H. Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Athamneh AA, Khaleel A, Ahmad L, Qaraqish R, Altaha AE, Khalaf H. Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 12, 2026]; 15(7): 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 Harvard Style Athamneh, A. A., Khaleel, . A., Ahmad, . L., Qaraqish, . R., Altaha, . A. E. & Khalaf, . H. (2025) Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. Open Vet. J., 15 (7), 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 Turabian Style Athamneh, Ahmad Al, Anas Khaleel, Leena Ahmad, Rahaf Qaraqish, Abed Elrahman Altaha, and Hanaa Khalaf. 2025. Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 Chicago Style Athamneh, Ahmad Al, Anas Khaleel, Leena Ahmad, Rahaf Qaraqish, Abed Elrahman Altaha, and Hanaa Khalaf. "Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Athamneh, Ahmad Al, Anas Khaleel, Leena Ahmad, Rahaf Qaraqish, Abed Elrahman Altaha, and Hanaa Khalaf. "Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis." Open Veterinary Journal 15.7 (2025), 3097-3103. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Athamneh, A. A., Khaleel, . A., Ahmad, . L., Qaraqish, . R., Altaha, . A. E. & Khalaf, . H. (2025) Investigating enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7) in live sheep from Central Jordan: Prevalence and antibiotic sensitivity analysis. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3097-3103. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.21 |