| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2815-2822 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2815-2822 Research Article Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing methodKadek Rachmawati1*, Kuncoro Puguh Santoso1, Rochmah Kurnijasanti1 and Aswin Rafif Khairullah21Division of Basic Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 2Research Center for Veterinary Science, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Kadek Rachmawati. Division of Basic Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. Email: kadek-r [at] fkh.unair.ac.id Submitted: 08/03/2025 Revised: 27/05/2025 Accepted: 29/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

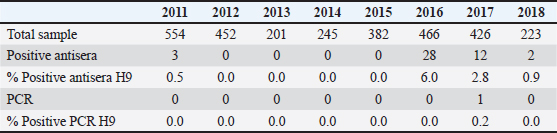

AbstractBackground: Influenza A virus subtype H9 is enzootic in portions of North and Central Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, where it significantly reduces the chicken industry’s profitability. The H9N2 virus was reported in Indonesia in late 2016, causing decreased egg production and increased mortality. Research on the H9N2 virus is important as an early warning system for the reassortment of potentially pandemic viruses such as HPAI virus subtype H5N1. Aim: This tracking study aimed to isolate and identify the H9N2 virus in laying hens from samples collected from 2011 to 2018 in Indonesia. Methods: Sequencing was performed on 2,949 samples obtained from tracheal and cloacal swabs after examination for the H9N2 virus using real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Results: One positive sample was from West Java in 2017. The results of the phylogenetic analysis revealed that this virus belongs to the China–Vietnam–Indonesia lineage and is related to the A/chicken/West Java/VSN791/2017(H9N2) and A/chicken/Viet Nam/QN-2576/2015(H9N2) viruses. Conclusion: As an early warning system for AI outbreaks, active surveillance is required to track the progress of LPAI viruses like H9N2. Keywords: Chickens, Indonesia, Influenza, H9N2, Virus. IntroductionInfluenza A virus belonging to the Orthomyxoviridae family has a segmented, negative-sense RNA genome that encodes for 10 different proteins (Hao et al., 2020). The influenza A virus combinations of the surface proteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) result in a variety of virus variants, including H1N1, H5N6, and H9N2 (Peacock et al., 2019). The pathogenicity of avian influenza viruses (AIVs) in chickens and the molecular markers of their HA proteins can be used to classify the virus into two groups (Ayuti et al., 2024). Highly pathogenic avian influenza, such as H7 and H5 show high pathogenicity in chickens and contains multiple basic amino acids in HA, allowing the virus to replicate systemically in poultry (Luczo et al., 2015). Low-pathogenic avian influenza virus (LPAIV) is characterized by low pathogenicity at the monobasic amino acid cleavage site in HA, which only allows HA cleavage by proteases that limit viral replication to the respiratory and digestive tracts only, where these proteases are highly expressed (de Bruin et al., 2022). The H9N2 virus is a LPAIV subtype found worldwide (Carnaccini and Perez, 2020). Because the virus has the potential to either directly cause the next influenza pandemic as the H9N2 subtype pandemic virus or indirectly cause it by internal gene donation to the H7 and H5 pandemic viruses, it is currently the focus of intense investigation (Peacock et al., 2019). In Asia and Africa, domestic poultry has become enzootic because of the presence of the avian influenza virus subtype H9N2 (AIV-H9N2) (Jonas et al., 2018). Despite falling under the low pathogenic chicken influenza category, this virus damages the poultry business financially and may be harmful to human health (Kim, 2018). Additionally, internal proteins from this subtype encode gene sequences that promote the formation of new strains (Han et al., 2019). There are no prior reports of AIV-H9N2 in Indonesia. At the end of 2016 and the beginning of 2017, there was an increase in mortality rates and a decrease in egg production in several livestock sectors (Nurliani et al., 2024). Tests have been conducted on AIV-H9N2, and 50% of the cases were found to be positive for AIV-H9N2 (Jonas et al., 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to conduct tracking research on the presence of the H9 virus in Indonesia. This study aimed to characterize the genetics of the AI virus subtype H9N2 in Indonesia using samples collected from 2011 to 2018 by the AIRC laboratory PNF research team, Surabaya, Indonesia. Materials and MethodsSample collectionThe samples were collected from chicken trachea and cloaca swabs collected from several regions in Indonesia. Virus isolation was carried out by inoculating TAB aged 9–11 days. Allantois samples were collected and tested using HA and HI antisera tests. RNA extraction and RT–PCRRNA extraction was performed on allantoic fluid samples with positive HA values using a viral RNA micro kit (Qiagen, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was then amplified using Realtime PCR with the primers Primary H9 Forward: ATG GGG TTT GCT GCC, Primary H9 Reverse: TTA TAT ACA AAT GTT GCA CTC TG, Probe H9 /56-FAM/TTC TGG GCC ATG TCC AAT GG/36-TAMSp/. The reaction cycle included 10 minutes of amplification at 95°C and 10 minutes of reverse transcription at 45°C. A total of 45 cycles, which include 15 seconds of denaturation at 95°C and 45 seconds of annealing/extension at 60°C. The examined samples showed positive results if the Ct value was less than 40, undetermined if the Ct value was between 40 and 45, and negative if the Ct value was larger than 45, using a threshold value of 0.1. Sequencing and phylogenetic analysisThe sequencing results can be obtained directly from the sequencing machine, Genetic Analyzer, and then compared with the nucleotide sequence data of the reference virus gene fragment of the virus nucleotide sequence in GenBank. For the H9N2 virus, the viruses Qa/HK/G1/97, Y439=Dk/HK/Y439/97, Ck/BJ/1/94, DK/HK/d73/76, Ck/SH/F/98, and Ck/Kor/323/96 were used as reference viruses. We used software called Genetyc Ver 14 to accomplish this. Using genetic analysis software (MEGA) version 6, we created phylogenetic trees by employing the Tamura-Nei model with bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates) and the maximum likelihood technique. Ethical approvalNot needed for this study. ResultsA total of 2,949 samples of layer chickens in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 were collected and tested for the H9N2 virus. After the Antisera test was performed to screen samples with positive HA titers, further tests were performed on samples with positive antisera titers. The results of the real-time PCR test revealed that one sample was positive for the H9N2 virus in 2017. The results are shown in Table 1. Table 1. HI test results of H9 antisera in samples from 2011 to 2018.

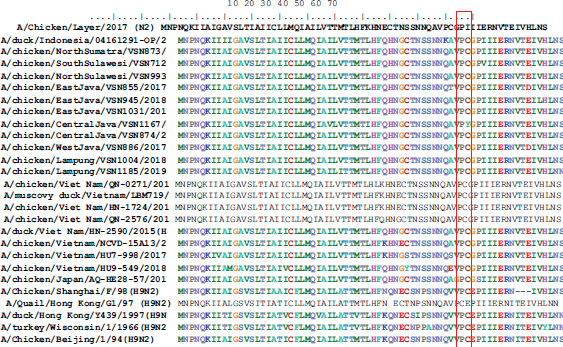

The HA protein has a special region called the cleavage site region, which is the region where the HA0 gene is cleaved into HA1 and HA2, so that the influenza virus becomes infective when a virus infection occurs. After predicting the amino acid sequence of the HA protein using Genetyc ver.14 Software, it was obtained as in Table 2. In the cleavage site region, the virus found in this study showed the PSRSSR/GL motif (P = Proline; S = Serine; R = Arginine; S = Serine; S = Serine; R/G = Arginine/Glycine and L = Leucine), which is a monobasic cleavage site, indicating that the virus is low pathogenic. Table 2. Amino acid sequence of the H9 virus HA protein.

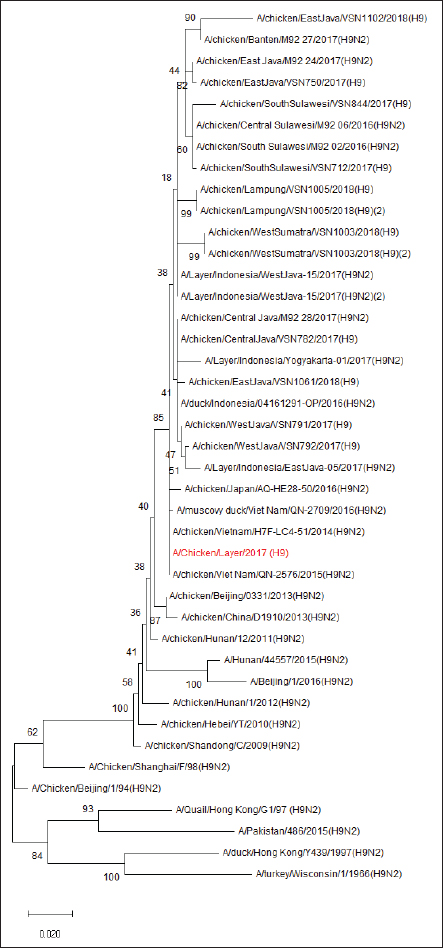

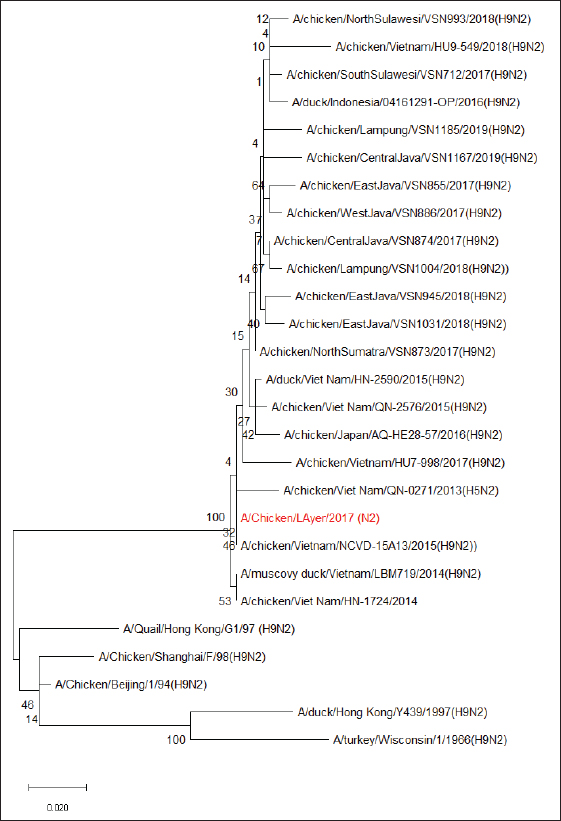

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic analysis of HA segment of AIV-H9N2. The results of the amino acid analysis of the NA gene from the isolated H9N2 virus illustrated that the NA stalk region had no amino acid deletions (Table 3). The H9N2 virus obtained from this analysis, based on the NA gene, showed a close relationship with the H9N2 virus originating from Vietnam in 2015 (Fig. 2). Table 3. Amino acid sequence of the H9 virus NA protein.

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic analysis of the NA segment of the AIV-H9N2. DiscussionThis study conducted trace research on the genetic characterization of the AI virus subtype H9N2 in Indonesia using samples collected from 2011 to 2018. According to these findings, West Javan chicken farms in 2017 had the AI virus subtype H9N2. Infection by the AI virus subtype H9N2 has not been previously reported in Indonesia. Reports of higher mortality and lower egg production surfaced in late 2016 and early 2017. Then, tests were carried out on several infectious virus agents, such as ND, IB, and H5N1 in layer, breeder, and broiler chicken farms, but not all showed positive results. After retesting the AI virus subtype H9N2, 50% of positive cases were obtained, which had the highest similarity to the Vietnam/LBM719/2014 virus. LPAIV H9N2 has been circulating in Indonesia since 2017 and has caused a decline in the quality and quantity of egg production in chickens, resulting in losses in the poultry farming industry (Dharmayanti et al., 2020). Research on antibody titers conducted by Kencana et al. (2023) showed the presence of antibodies against the AI virus subtype H9N2 in laying hens. Based on these findings, it can be interpreted that the possibility of the H9N2 virus circulating in Indonesia since 2013 in cats, and the isolation of the AI virus subtype H9N2 in Indonesia was detected only in poultry in 2016–2017. The AI virus isolate subtype H9N2 in this study was subjected to sequencing tests to determine the amino acids in the cleavage site region. The HA gene’s amino acid sequence at the cleavage site, which had a monobasic cleavage site and a PSRSSR pattern, indicated that the virus’s molecular characteristics were low pathogenicity. The pathogenicity of viruses is closely associated with the HA gene, particularly when considering the sequence in the HA gene’s cleavage site region (Chan et al., 2020). If the cleavage site is filled with a single Arginine residue, the virus is cleaved by host proteases to a limited extent, resulting in mild infection (Bertram et al., 2010). Meanwhile, if the cleavage site is filled with multiple basic amino acids, the virus will be broken down by a protease with a wider reach, resulting in a systemic and severe infection (Song et al., 2021). There were no amino acid deletions in the NA stalk region of the isolated AI virus subtype H9N2 in this investigation. Sorrell et al. (2010) state that amino acid deletions in the NA stalk region are further indication that chickens have adapted to the AIV. The results of the phylogenetic analysis of the AI virus subtype H9N2 that have been found, based on the HA gene, are included in the China–Vietnam–Indonesia (CVI) lineage and are close to the A/chicken/Viet Nam/QN-2576/2015 and A/chicken/WestJava/ VSN791/2017 viruses. The H9N2 viral sequencing data from China and Vietnam formed a cluster with the viruses in this investigation. In accordance with research conducted by Rehman et al. (2022), who identified the H9N2 virus in Indonesia. The existence of the CVI lineage was formed due to differences from the BJ94 lineage. This suggests that the H9N2 virus, which was active in Indonesia between 2016 and 2017 is a member of the BJ/94-like lineage, which is most common in China. Three lineages of the Eurasian H9N2 virus have been identified: A/chicken/ Beijing/1/94, A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/1997, and A/ chicken/Hong Kong/Y439/1997. The BJ/94 lineage virus is commonly found in Cambodia, CVI, and Myanmar (Peacock et al., 2019). Phylogenetic analysis of the NA gene of both isolates of the AI virus subtype H9N2 belongs to the Y439- lineage and has a closeness to the virus originating from Vietnam, A/Chicken/Vietnam/NCVD-15A13/2015 (H9N2). Based on the results of the phylogenetic analysis of the HA and NA genes, it is likely that the H9N2 virus that entered Indonesia originated from Vietnam and was carried by wild birds due to transportation or migration. The results of this study confirmed the presence of LPAIV H9N2 in chicken samples collected in Indonesia. These findings are consistent with those from China, where H9N2 was the most common subtype of AI virus found in all provinces (Shi et al., 2014), and the overall prevalence of AI viruses in chickens varied from 21% to 36% in Hubei, 34%–46% in Zhejiang province (Chen et al., 2016), and 15.7% in Hunan (Huang et al., 2015). The most common AI virus subtype ever identified in North Vietnam is H9N2 (Thuy et al., 2016). Despite the fact that many subtypes of AI viruses, such as H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H10 viruses, are known to circulate in Vietnamese wild and domestic ducks, detailed sequencing data revealed that only AIV subtypes H5 and H9 have been shown to circulate endemically in chickens (Nguyen et al., 2005; Jadhao et al., 2009; Hotta et al., 2012; Nomura et al., 2012; Okamatsu et al., 2013; Takakuwa et al., 2013). Future human health could be at risk due to the spread of LPAIV H9N2 in poultry and the possibility of reassortment. LPAIV H9N2 is known to have unique characteristics among other LPAIV viruses because this virus has the ability to infect various species including humans and is a donor of genetic material for other influenza virus subtypes (Pusch and Suarez, 2018). Co-circulation between the AI virus subtype H9N2 and viruses circulating in the field, such as the AI virus subtype H5N1, can cause reassortment, which produces new viruses with higher pathogenicity (Ripa et al., 2021). ConclusionEconomic losses indicate that the H9N2 virus poses a serious danger to laying hen and breeder farms. Biosecurity and vaccination initiatives have been initiated as a result of the H9N2 virus’s widespread and swift spread throughout numerous Indonesian regions. Continuous active surveillance to monitor HPAI and LPAI virus activity in the field is necessary for the early warning system to detect AI outbreaks. The main biosecurity recommended in layer chicken farming includes controlling the traffic of people entering and leaving the cage facility, cleaning and disinfecting the cage, preventing the emergence of infectious diseases through vaccination programs, monitoring chicken health such as monitoring antibodies through serological tests, maintaining personal hygiene of cage children, and controlling pests and animals other than poultry to prevent the entry of vectors that cause infectious diseases. AcknowledgmentThe authors thanks to Universitas Airlangga. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. FundingThe authors thank the Directorate of Research and Community Service and Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Airlangga University for the PUF Fiscal Year 2018 (number: 1722/UN3.1.6/LT/2018). Author’s contributionsLaboratory work and data collection: KR. Field sampling method: KPS. Data analysis and manuscript writing: RK. Research concept: ARK. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data availabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are available in the manuscript, and no additional data sources are required. ReferencesAyuti, S.R., Khairullah, A.R., Lamid, M., Al-Arif, M.A., Warsito, S.H., Silaen, O.S.M., Moses, I.B., Hermawan, I.P., Yanestria, S.M., Delima, M., Ferasyi, T.R. and Aryaloka, S. 2024. Avian influenza in birds: insights from a comprehensive review. Vet. World 17(11), 2544–2555. Bertram, S., Glowacka, I., Steffen, I., Kühl, A. and Pöhlmann, S. 2010. Novel insights into proteolytic cleavage of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Rev. Med. Virol. 20(5), 298–310. Carnaccini, S. and Perez, D.R. 2020. H9 influenza viruses: an emerging challenge. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 10(6), a038588. Chan, M., Leung, A., Hisanaga, T., Pickering, B., Griffin, B.D., Vendramelli, R., Tailor, N., Wong, G., Bi, Y., Babiuk, S., Berhane, Y. and Kobasa, D. 2020. H7N9 influenza virus containing a polybasic HA cleavage site requires minimal host adaptation to obtain a highly pathogenic disease phenotype in mice. Viruses 12(1), 65. Chen, L.J., Lin, X.D., Guo, W.P., Tian, J.H., Wang, W., Ying, X.H., Wang, M.R., Yu, B., Yang, Z.Q., Shi, M., Holmes, E.C. and Zhang, Y.Z. 2016. Diversity and evolution of avian influenza viruses in live poultry markets, free-range poultry and wild wetland birds in China. J. Gen. Virol. 97(4), 844–854. de Bruin, A.C.M., Funk, M., Spronken, M.I., Gultyaev, A.P., Fouchier, R.A.M. and Richard, M. 2022. Hemagglutinin subtype specificity and mechanisms of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus genesis. Viruses 14(7), 1566. Dharmayanti, N.L.P.I., Indriani, R. and Nurjanah, D. 2020. Vaccine efficacy on the novel reassortant H9N2 virus in Indonesia. Vaccines (Basel) 8(3), 449. Han, L., He, W., Yan, H., Li, X., Wang, C., Shi, Q., Zhou, T. and Dong, G. 2019. The evolution and molecular characteristics of H9N2 avian influenza viruses in Jiangxi of China. J. Med. Virol. 91(4), 711–716. Hao, W., Wang, L. and Li, S. 2020. Roles of the non- structural proteins of influenza A virus. Pathogens 9(10), 812. Hotta, K., Takakuwa, H., Le, Q.M., Phuong, S.L., Murase, T., Ono, E., Ito, T., Otsuki, K. and Yamashiro, T. 2012. Isolation and characterization of H6N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses from Ducks in Hanoi, Vietnam. Virus Res. 163(2), 448–453. Huang, Y., Li, X., Zhang, H., Chen, B., Jiang, Y., Yang, L., Zhu, W., Hu, S., Zhou, S., Tang, Y., Xiang, X., Li, F., Li, W. and Gao, L. 2015. Human infection with an avian influenza A (H9N2) virus in the middle region of China. J. Med. Virol. 87(10), 1641–1648. Jadhao, S.J., Nguyen, D.C., Uyeki, T.M., Shaw, M., Maines, T., Rowe, T., Smith, C., Huynh, L.P., Nghiem, H.K., Nguyen, D.H., Nguyen, H.K., Nguyen, H.H., Hoang, L.T., Nguyen, T., Phuong, L.S., Klimov, A., Tumpey, T.M., Cox, N.J., Donis, R.O., Matsuoka, Y. and Katz, J.M. 2009. Genetic analysis of avian influenza A viruses isolated from domestic waterfowl in live-bird markets of Hanoi, Vietnam, preceding fatal H5N1 human infections in 2004. Arch. Virol. 154(8), 1249–1261. Jonas, M., Sahesti, A., Murwijati, T., Lestariningsih, C.L., Irine, I., Ayesda, C.S., Prihartini, W. and Mahardika, G.N. 2018. Identification of avian influenza virus subtype H9N2 in chicken farms in Indonesia. Prev. Vet. Med. 159(1), 99 -105. Kencana, G.A.Y., Suartha, I.N., Widyanjaya, A.A.G.F., Nariasih, N.K.C. and Sudirman, F.X. 2023. Immunity of layer chicken post-vacination with avian influenza subtype H9N2 vaccine. J. Vet. 24(2), 194–200. Kim, S.H. 2018. Challenge for one health: co- circulation of zoonotic H5N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses in Egypt. Viruses 10(3), 121. Luczo, J.M., Stambas, J., Durr, P.A., Michalski, W.P. and Bingham, J. 2015. Molecular pathogenesis of H5 highly pathogenic avian influenza: the role of the haemagglutinin cleavage site motif. Rev. Med. Virol. 25(6), 406–430. Nguyen, D.C., Uyeki, T.M., Jadhao, S., Maines, T., Shaw, M., Matsuoka, Y., Smith, C., Rowe, T., Lu, X., Hall, H., Xu, X., Balish, A., Klimov, A., Tumpey, T.M., Swayne, D.E., Huynh, L.P., Nghiem, H.K., Nguyen, H.H., Hoang, L.T., Cox, N.J. and Katz, J.M. 2005. Isolation and characterization of avian influenza viruses, including highly pathogenic H5N1, from poultry in live bird markets in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 2001. J. Virol. 79(7), 4201–4212. Nomura, N., Sakoda, Y., Endo, M., Yoshida, H., Yamamoto, N., Okamatsu, M., Sakurai, K., Hoang, N.V., Nguyen, L.V., Chu, H.D., Tien, T.N. and Kida, H. 2012. Characterization of avian influenza viruses isolated from domestic ducks in Vietnam in 2009 and 2010. Arch. Virol. 157(2), 247–257. Nurliani, Rosada, I., Sirajuddin, S.N., Nurhapsa, Al Tawaha, A.R., Al-Tawaha, A.R.M.S. and Karnwal, A. 2024. Factors affecting the trend in the number of chicken eggs produced in South Sulawesi. Rev. Electron. Vet. 25(1), 108–119. Okamatsu, M., Nishi, T., Nomura, N., Yamamoto, N., Sakoda, Y., Sakurai, K., Chu, H.D., Thanh, L.P., Van Nguyen, L., Van Hoang, N., Tien, T.N., Yoshida, R., Takada, A. and Kida, H. 2013. The genetic and antigenic diversity of avian influenza viruses isolated from domestic ducks, muscovy ducks, and chickens in northern and southern Vietnam, 2010- 2012. Virus Genes 47(2), 317–329. Peacock, T.H.P., James, J., Sealy, J.E. and Iqbal, M. 2019. A global perspective on H9N2 avian influenza virus. Viruses 11(7), 620. Pusch, E.A. and Suarez, D.L. 2018. The multifaceted zoonotic risk of H9N2 avian influenza. Vet. Sci. 5(4), 82. Rehman, S., Rantam, F.A., Batool, K., Shehzad, A., Effendi, M.H., Witaningrum, A.M., Bilal, M. and Purnama, M.T.E. 2022. Emerging threats and vaccination strategies of H9N2 viruses in poultry in Indonesia: a review. F1000Res 11(1), 548. Ripa, R.N., Sealy, J.E., Raghwani, J., Das, T., Barua, H., Masuduzzaman, M., Saifuddin, A.K.M., Huq, M.R., Uddin, M.I., Iqbal, M., Brown, I., Lewis, N.S., Pfeiffer, D., Fournie, G. and Biswas, P.K. 2021. Molecular epidemiology and pathogenicity of H5N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses in clinically affected chickens on farms in Bangladesh. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 10(1), 2223–2234. Shi, W., Li, W., Li, X., Haywood, J., Ma, J., Gao, G.F. and Liu, D. 2014. Phylogenetics of varied subtypes of avian influenza viruses in China: potential threat to humans. Protein Cell 5(4), 253–257. Song, W., Huang, X., Guan, W., Chen, P., Wang, P., Zheng, M., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Chen, H. and Wang, X. 2021. Multiple basic amino acids in the cleavage site of H7N9 hemagglutinin contribute to high virulence in mice. J. Thorac Dis. 13(8), 4650–4660. Sorrell, E.M., Song, H., Pena, L. and Perez, D.R. 2010. A 27-amino-acid deletion in the neuraminidase stalk supports replication of an avian H2N2 influenza A virus in the respiratory tract of chickens. J. Virol. 84(22), 11831–1140. Takakuwa, H., Yamashiro, T., Le, M.Q., Phuong, L.S., Ozaki, H., Tsunekuni, R., Usui, T., Ito, H., Yamaguchi, T., Ito, T., Murase, T., Ono, E. and Otsuki, K. 2013. The characterization of low pathogenic avian influenza viruses isolated from wild birds in northern Vietnam from 2006 to 2009. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36(6), 581–590. Thuy, D.M., Peacock, T.P., Bich, V.T.N., Fabrizio, T., Hoang, D.N., Tho, N.D., Diep, N.T., Nguyen, M., Hoa, L.N.M., Trang, H.T.T., Choisy, M., Inui, K., Newman, S., Trung, N.V., van Doorn, R., To, T.L., Iqbal, M. and Bryant, J.E. 2016. Prevalence and diversity of H9N2 avian influenza in chickens of Northern Vietnam, 2014. Infect. Genet. Evol. 44(1), 530–540. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Rachmawati K, Santoso KP, Kurnijasanti R, Khairullah AR. Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 Web Style Rachmawati K, Santoso KP, Kurnijasanti R, Khairullah AR. Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=246437 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Rachmawati K, Santoso KP, Kurnijasanti R, Khairullah AR. Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Rachmawati K, Santoso KP, Kurnijasanti R, Khairullah AR. Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 Harvard Style Rachmawati, K., Santoso, . K. P., Kurnijasanti, . R. & Khairullah, . A. R. (2025) Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 Turabian Style Rachmawati, Kadek, Kuncoro Puguh Santoso, Rochmah Kurnijasanti, and Aswin Rafif Khairullah. 2025. Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 Chicago Style Rachmawati, Kadek, Kuncoro Puguh Santoso, Rochmah Kurnijasanti, and Aswin Rafif Khairullah. "Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Rachmawati, Kadek, Kuncoro Puguh Santoso, Rochmah Kurnijasanti, and Aswin Rafif Khairullah. "Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2815-2822. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Rachmawati, K., Santoso, . K. P., Kurnijasanti, . R. & Khairullah, . A. R. (2025) Isolation and identification of the H9N2 virus that caused the decline in poultry egg production in Indonesia from 2011 to 2018 using the RT–PCR-sequencing method. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2815-2822. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.50 |