| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2789-2797 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2789-2797 Research Article Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheepArif Wicaksono1, Aris Haryanto1, Alek Ibrahim2, Anggita Suryandari1, Rana Ayuningtyas Adhi Puspita1, Medania Purwaningrum11Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 2Research Center for Animal Husbandry, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Cibinong, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Medania Purwaningrum. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Email: medania [at] ugm.ac.id Submitted: 16/01/2025 Revised: 14/05/2025 Accepted: 24/04/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

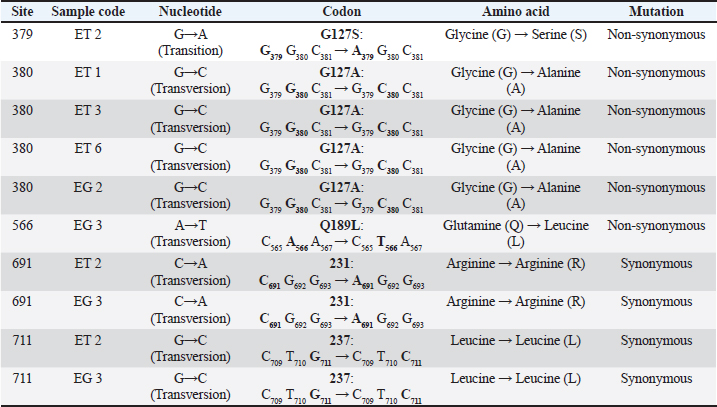

AbstractBackground: Scrapie is a deadly neurodegenerative transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) that affects sheep and goats. TSEs are a consequence of polymorphisms of the prion protein gene PRNP, which result in misfolded prion proteins. They are transmitted through contact with the abnormal proteins (prions). Currently, there are no data regarding the identification of PRNP variability in Indonesian sheep breeds. Aim: This study aimed to identify variants of the PRNP gene and classify the risk of scrapie disease genotypically in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Methods: DNA isolates from the blood samples of thin-tailed (ET) and fat-tailed (EG) sheep were amplified with the forward primer 5’-AAGCCACATAGGCAGTTGGA-3’and thereverse primer 5’-GAGACACCACCACTACAGGG-3’. A total of 10 samples of polymerase chain reaction products were sequenced and analyzed with molecular evolutionary genetics analysis v.11 software. The data were multiply aligned with comparison samples from GenBank. Results: We identified 10 nucleotide variations and 11 single-nucleotide polymorphisms at sites 379, 380, 566, 691, and 711. Four codon haplotypes were identified, namely G127A, G127S, G127V, and Q189L, as well as six genotypic variations at codon 127 and two at codon 189. All ET and EG samples had the scrapie codon A136L141R154Q171. Conclusion: The lack of resistant genotypes and protective alleles in the sheep in this study rendered them less genetically resistant to classical scrapie and more susceptible to atypical scrapie. This is the first study on the identification of PRNP gene variations in sheep in Indonesia. Our results suggest the need for further PRNP research in sheep, especially in Indonesia, to anticipate the risk of a scrapie outbreak and determine the relationship between PRNP variants and phenotypic characteristics of sheep. Keywords: Fat-tailed sheep, Genetic polymorphisms, PRNP, Scrapie, Thin-tailed sheep. IntroductionScrapie is a fatal type of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) found in sheep and goats. TSEs are neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system (CNS) caused by proteinaceous infectious particles known as prions. These are host- encoded cellular prion proteins (PrPc) that undergo a post-translational conformational shift to a proteinase- resistant form (PrPSc). Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy occurs when the normal α-helical protein PrPc encoded on the gene locus PRNP in the host’s genomes comes into contact with the pathogenic isoform PrPSc with a β-sheet enriched three-dimensional structure. This causes an autocatalytic conversion process that turns PrPc into thermodynamically stable PrPSc by causing aberrant protein folding and aggregation (Haik and Brandel, 2014). When the two isoforms come into contact, this process is repeated over time, causing PrPSc to build up in the body and induce TSE (Igel-Egalon et al., 2017). Prions cause Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sporadic and genetic type of CJD); kuru (environmentally acquired type); and Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker disease and fatal familial insomnia (hereditary type) in humans, chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle, and scrapie in sheep and goats (Thumdee et al., 2007; Prusiner, 1991). Between 1986 and 2004 in the United Kingdom, there was an immense epidemic of TSE that affected more than 4 million cattle (Smith and Bradley, 2003). Although it was first seen in Europe more than 250 years ago, the first cases of scrapie in the United States were not until 1947. This has resulted in an estimated annual loss between 1947 and 2001 of $20 million a year (DeSilva et al., 2003). Animal prion diseases are a serious health concern, as evidenced by the emergence of BSE and its transmission to humans in the late 1990s as the novel TSE variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) (Belay and Schonberger, 2005). The secondary person-to-person transmission of vCJD through blood products has a further potential impact on public health. Research on non-human primates and human PRNP transgenic mice has found that some prion diseases, including classical scrapie, L-type atypical BSE, and CWD, have zoonotic potential (Bedi et al., 2022). TSE is associated with the PRNP gene, and polymorphisms of PRNP cause scrapie susceptibility (Li et al., 2018). Lung, heart, skeletal muscle, spleen, intestinal tract, ovarian, and testicular tissue; the CNS; the lymph nodes; and lymphocytes all express high levels of PRNP (Bendheim et al., 1992; McBride et al., 1992; Mabbott et al., 1997; Pammer et al., 1998). The typical PRNP protein PrPc is found on outer cell surfaces. This is bound to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor (Stahl et al., 1990). This protein has various cellular functions, including the regulation of copper ion concentrations as antioxidant activity (Brown et al., 2001; Klamt et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2002), the transduction of neuroprotective signals, and the prevention of apoptosis in retinal cells (Chiarini et al., 2002). Ovine PRNP has three exons and two introns located on chromosome 13. The complete open reading frame (ORF) consists of 768 bp, resulting in a primary protein product of 256 amino acids in exon 3 of the gene (Tranulis, 2002). Polymorphisms of ovine PRNP affect not only susceptibility to scrapie but also its incubation period and clinical signs of disease progression. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the DNA cause the majority of polymorphisms in PRNP, which often lead to single amino acid changes. Of particular interest are polymorphisms at codons 136, 141, 154, and 171 within the ORF, as these are associated with scrapie susceptibility in sheep. There are five scrapie genotype risk classifications: R5 (highest genetic susceptibility), R4 (genetic susceptibility), R3 (low genetic resistance), R2 (genetic resistance), and R1 (highest genetic resistance) (Goldmann, 2008). PRNP research has been widely conducted with various sheep breeds in multiple countries (Tranulis, 2002; DeSilva et al., 2003; Goldmann, 2008; Li et al., 2018). However, despite PRNP research on seven Indonesian goat breeds (Pakpahan et al., 2023), there have been no PRNP studies on Indonesian sheep. Therefore, research is needed into the identification of PRNP gene variability in sheep in Indonesia. Although no scrapie cases have been recorded to date in Indonesia due to inadequate passive surveillance systems, it is importance to characterize the PRNP gene in some sheep in Indonesia as an initial effort to anticipate the risk of the emergence of scrapie disease in Indonesia. Moreover, there is the zoonotic potential of classical scrapie, and the latest findings that amyloid-β, α-synuclein, and other proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s diseases, and other neurodegenerative illnesses have recently been found to possess prion characteristics, such as transmission to animals. Given the contemporary longevity society, those findings suggest that diseases caused by various prions seem to pose a hazard (Bedi et al., 2022; Saitoh and Mizusawa, 2024). Genetic studies regarding scrapie disease also could provide foundational knowledge for early risk identification through the presence or the absence of alleles associated with susceptibility or resistance to scrapie, prevention and preparedness through breeding planning strategies, and surveillance enhancement and suggest scientific and policy insights into the authorities for biosecurity and economic relevant in Indonesia (Cassmann and Greenlee, 2019). Materials and MethodsEthics statementsEthical approval (approval no. 002/EC-FKH/Int./2019) date for this article is January, 8th 2019; the National Political Unity date is February 19th, 2019 for Yogyakarta Special District (approval no. 074/1850/ Kesbangpol/2019) and East Java District (approval no. 074/1852/Kesbangpol/2019). Sample collection and preparationBlood samples were collected from 10 thin-tailed sheep in the Sleman and Bantul regencies of Yogyakarta Special District (sample code ET 1–ET 10) and 10 fat- tailed sheep in the Pasuruan regency of the East Java province (sample code EG 1–EG 10). These are the two main sheep in Indonesia. Using a 3-cc syringe, the blood samples were collected from the jugular vein after the injection point had been cleansed with alcohol. The blood samples were taken in vacutainer tubes containing the anticoagulant ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and stored in a cooler box before being transported to the lab for further analysis. The samples were collected between April 2019 and March 2021. This study was conducted at the Laboratory of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, between November 2023 and March 2024. DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, and sequencing of PRNPGenomic DNA was isolated using a commercial extraction kit (PureLinkTM Genomic DNA Mini Kits, Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. The primer PRNP-F (5’-AAG CCA CAT AGG CAG TTG GA-3’) and the reverse primer PRNP-R (5’-GAG ACA CCA CCA CTA CAG GG-3’) were used to amplify the PRNP gene by PCR, generating a PCR product of 852 bp. The PCR reaction consisted of 3 µl of DNA template, 20 µl of MyTaq™ HS Red Mix (Meridian Bioscience, Ohio, USA), 14 µl of ddH2O, 1.5 µl of forward primer, and 1.5 µl of reverse primer. A Cleaver® GTC965 (Cleaver Scientific Ltd., Rugby, UK) was used for PCR amplification with the program: 5 minutes of pre-denaturation at 96°C; 35 cycles each of denaturation at 96°C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 57°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 90 seconds; and a final extension at 72°C for 4 minutes. The DNA amplification was checked on an ultraviolet illuminator (UVP® 95-0225-02, Los Angeles, USA) after electrophoresis at 90 mV for 35 minutes using a 1.5% agarose gel. The PCR products were sent to Genetika Science Indonesia, Tangerang, Banten (ET 1 and EG 5) and to the Integrated Research and Testing Laboratory, Universitas Gadjah Mada (ET 2, ET 3, ET 4, ET 6, EG 1, EG 2, EG 3, and EG 6) for sequencing (10 of the 20 samples were sequenced). Data analysisMolecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis, v. 11.0 software was used to analyze the sequence products. The ClustalW program was used to align the PRNP region sequences of the thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. The variation in the nucleotide sequence of exon 3 of the PRNP region was used to determine the genetic profile analysis. The GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov) sequence AJ223072.1 was used as a reference sequence for the ovine PRNP gene (Goldmann et al., 1999). Ten GenBank sequences with the accession numbers MG214327.1, FJ792605.1, AJ223072.1, GQ380576.1, AY907685.1, AY907693.1, AY907683.1, JF514135.1, DQ272623.1, and DQ272637.1 were used as comparators of the PRNP gene. ResultsIn the coding PRNP region of thin-tailed and fat- tailed sheep, we observed 10 nucleotide variations and 11 SNPs. Substitution of guanine nucleotides with adenine nucleotides (transition mutation) at site 379 in ET 2 resulted in a change of the amino acid of codon 127 from glycine to serine (G127S). A transversion mutation of guanine to cytosine nucleotide substitution at site 380 in ET 1, ET 3, ET 6, and EG 2 resulted in the homozygous haplotype codon G127A. There was a non-synonymous mutation at site 566 in EG 3 from the transversion mutation of nucleotide substitution, resulting in the homozygous haplotype codon Q189L. Four synonymous mutations at sites 691 and 711 in ET 2 and EG 3 were also observed. Details of the substitution mutations in ET and EG are shown in Table 1. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms at sites 380, 691, and 711 resulted in four non-synonymous and seven synonymous mutations in locations with strong or S (C & G), keto or K (T & G), pyrimidine or Y (C & T), and amino or M (A & C) nucleotides in ET and EG. Details of the SNPs in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep are shown in Table 2. A total of 10 non-synonymous and 11 synonymous mutations from nucleotide substitution and SNP were observed in ET and EG. There were six genotypic variations at codon 127 and two at codon 189. These are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. Interestingly, all samples had the A136L141R154Q171 scrapie codon. Table 1. Substitution mutations in thin-tailed (ET) and fat-tailed (EG) Indonesian sheep.

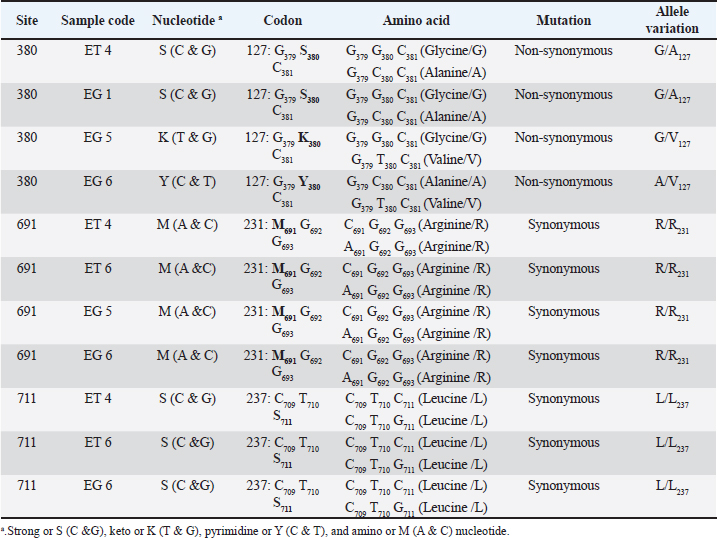

Table 2. SNP mutations in thin-tailed (ET) and fat-tailed (EG) Indonesian sheep.

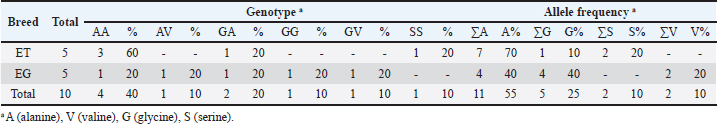

Table 3. PRNP genotype and allele frequencies in codon 127 of thin-tailed (ET) and fat-tailed (EG) Indonesian sheep.

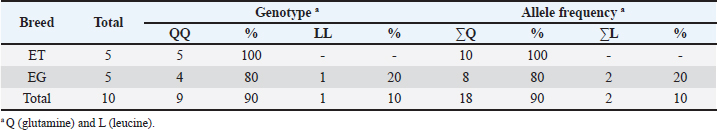

Table 4. PRNP genotype and allele frequencies in codon 189 of thin-tailed (ET) and fat-tailed (EG) Indonesian sheep.

DiscussionNucleotide substitution mutations in the coding region of PRNPWe observed 10 nucleotide substitutions in the sheep samples: six in thin-tailed and four in fat-tailed sheep. There were six non-synonymous and four synonymous mutations, and nine of the ten were transversion mutations (Table 1). We observed the homozygous haplotype codons G127S, G127A, and Q189L in non- synonymous mutations. Several previous studies have reported variants such as G127A (Heaton et al., 2003; Goldmann et al., 2005) and G127S in sheep prion proteins (Gombojav et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Lan et al., 2006; Kdidi et al., 2014). Amino acids at codons 126 and 127 were in the highly conserved glycine-rich motif GAVVG126G127LGGYMLG. This glycine- rich motif could protect against the development of prion diseases through the inhibition of amyloid fibril formation (Zhang et al., 2013). Recent research has identified polymorphisms at this position that suggest it to be important to the normal cellular functions of prion proteins (Vitale et al., 2019). Sequence variations in palindrome residue (PRNP 113–120) and glycine repeat regions (PRNP 124–128) are complementary and may alter the structural pliability of cellular prion proteins and could lead to a new type of scrapie in sheep (Goldmann, 2018; Teferedegn et al., 2020). Homozygous GAVVG126G127LGGYMLG, which could protect against the development of prion disease, was only observed in sample EG 3 in this study. While heterozygous GAVVG126G127LGGYMLG was observed in ET 4, EG 1, and EG 5, the effects of this heterozygous motif are not yet known. Polymorphisms such as Q189L have previously been reported in several studies (Gombojav et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Lan et al., 2006) as well as in Awassi sheep in Turkey, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia (Rashaydeh et al., 2023). We also saw AA, SS, and GG genotype variations in codon 127 and LL and QQ genotype variations in codon 189 from the substitution mutations. The frequency of the AA genotype in codon 127 was 40%, and those of the SS and GG genotypes were both 10%. The frequencies of the LL and QQ genotypes in codon 189 were 10% and 90%, respectively, in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. SNPs in the coding region of PRNPEleven SNPs were observed in the coding PRNP region at sites 380, 691, and 711. This resulted in four non- synonymous and seven synonymous mutations in thin- tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Heterozygous haplotype codons G127A and G127V from non-synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms and G/A127, G/V127, and A/V127 allele variations were observed at site 380. These polymorphisms have previously been reported (Heaton et al., 2003; G127V by Gombojav et al., 2004; G127A by Goldmann et al., 2005; Lan et al., 2006; Vaccari et al., 2007; Lan et al., 2014), as well as in Awassi sheep in Turkey, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia (Rashaydeh et al., 2023) and Kivirick sheep in Turkey (Oner et al., 2011). The highly polymorphic mutation that we observed at codon 127 closely resembles the pattern of scrapie susceptibility previously observed in Nigerian sheep (Adeola et al., 2023) and three indigenous Ethiopian sheep breeds (Teferedegn et al., 2020). The polymorphisms in the glycine-rich motif at codon 127 have the potential to alter the structural pliability of cellular prion proteins and introduce a novel form of scrapie in sheep (Rashaydeh et al., 2023). GA (20% frequency), GV (10% frequency), and AV (10% frequency) genotype variations from codon 127 were also seen from these mutations in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Codon scrapie in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheepCodon variants at positions 136, 154, and 171 are linked to classical scrapie (Goldmann, 2018). In this study, we found that all samples had a homozygous A136R154Q171 (ARQ/ARQ) codon. The A136R154Q171 (ARQ/ARQ) genotype is classified into group R3 (low genetic resistance to scrapie). Sheep with a homozygous ARQ genotype have average susceptibility to scrapie disease, whereas sheep with the ARQ/ARQ genotype and those with the VRQ carrier genotype are in the R5 group (highest susceptibility to scrapie). Langlade sheep in France with the ARQ/ARQ genotype were infected in parallel with VRQ carriers (Elsen et al., 1999), and 95% of Spanish rasa sheep infected with scrapie were found to have the ARQ/ARQ genotype (Acín et al., 2004). Similarly, a high percentage of scrapie cases in Germany, Spain, and Greece have been found to have the ARQ/ARQ genotype (Acín et al., 2004; Billinis et al., 2004; Lühken et al., 2007). Sheep with this genotype are more likely to die at a younger age relative to the level of scrapie risk. Scrapie also attacks sheep breeds with the ARQ/ARQ genotype that do not encode VRQ, such as Suffolks, and ARQ/ARQ scrapie cases are frequently younger sheep. In sheep with this genotype, there is typically a shorter scrapie incubation period than would be expected based on the level of susceptibility (Baylis et al., 2004). All thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep samples in this study had an R3 risk genotype classification or genetic with low resistance to classical scrapie. Classical scrapie is a naturally occurring infectious disease, whereas atypical scrapie appears to arise from the spontaneous misfolding of prions. It is known that scrapie can spread laterally among sheep. Direct touch and environmental contamination are the two ways in which such transmissions occur. The oral route is most efficient (Jeffrey and Gonzalez, 2007; van Keulen et al., 2008). The infectious placenta is the main source of infections. Depending on the offspring’s genotype, both infectiousness and PrPSc have been found in the fetal parts (Alverson et al., 2006; Lacroux et al., 2007). Polymorphisms in PRNP modulate susceptibility to both types of scrapie. Sheep with R1–R3 genotype classifications are most commonly infected with atypical scrapie (Goldmann, 2008; Benestad et al., 2008). However, while thousands of sheep have been infected with classical scrapie globally, the number of sheep infected with atypical scrapie is only in the hundreds. Atypical scrapie susceptibility is associated with codons 141 and 154 of the PRNP gene. The genotype with the AF141RQ allele has the highestsusceptibility to atypical scrapie, followed by the AHQ and AL141RQ genotypes (Goldmann, 2008). Thus, the thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep in this study (A136L141R154Q171 codon homozygous) were classified as a genotype susceptible to atypical scrapie. Previous studies have identified specific alleles linked to scrapie resistance and/or extended incubation periods in sheep, in addition to codon variants at positions 136, 154, and 171. In the United States, the M112T variant on ARQ haplotypes has been associated with scrapie resistance in orally inoculated Suffolk sheep (Laegreid et al., 2008). Sheep with variant T112ARQ are resistant to the development of classical scrapie (Zhang et al., 2004). The ARQ haplotypes M137T and N176K have been linked to scrapie resistance in Italian Sarda sheep that have been naturally infected, intracranially inoculated, and orally inoculated (Vaccari et al., 2007; Vaccari et al., 2009). The haplotypes T112ARQ, AT137RQ, AC151RQ, and ARQK176 have also been found to have scrapie resistance or protective variants (Ikeda et al., 1995; Thorgeirsdottir et al., 1999; Heaton et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004; Vaccari et al., 2007; Laegreid et al., 2008; Vaccari et al., 2009). In populations where ARR sheep are scarce or unavailable, genetically resistant ARQ sheep with these protective variants facilitate the eventual eradication of classical scrapie through genetic selection (Heaton et al., 2010). In this study, these protective allele variants and scrapie- resistant alleles were not found in thin-tailed or fat- tailed sheep. In addition to regulating TSEs, PRNP influences the economic productivity of healthy livestock, affecting factors such as cashmere wool yield, wool thickness (Lan et al., 2012), and goat milk production (Vitezica et al., 2013). PRNP affects the waistline, body length, and weight of cows (Yang et al., 2016). PRNP polymorphisms are significantly associated with phenotypic traits in sheep, including chest width in small-tailed Han sheep, chest circumference in Hu sheep, and tail length in Tong sheep (Li et al., 2018). The prevalence of scrapie is undetermined in many countries due to inadequate passive surveillance (Curcio et al., 2016). This is also true for Indonesia, where no cases of scrapie have been recorded to date. However, the genotype classifications for all the ET and EG samples in this study indicated having low resistance to classical scrapie and susceptibility to atypical scrapie due to a lack of the necessary resistant genotypes and protective alleles. These findings indicate the need for further research on the PRNP gene and its association with the phenotypic traits of Indonesian sheep. ConclusionScrapie is a serious disease in sheep that can have a profound economic impact. Its zoonotic potential makes it a public health risk. The sheep in this study were found to have poor genetic resistance to classical scrapie and were susceptible to atypical scrapie due to a lack of resistant genotypes and protective alleles. This study is the first to investigate the identification of PRNP gene variability in sheep in Indonesia. Further PRNP research is needed, especially in Indonesia, to anticipate the risk of new forms of scrapie and determine the relationships between PRNP and phenotypic characteristics of sheep. List of AbbreviationsBp, base pair; BSE, Bovine spongiform encephalopathy; CJD, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease; CNS, central nervous system; CWD, chronic wasting disease; EG, fattailed sheep; ET, thin-tailed sheep; L-BSE, L-type atypical BSE; MEGA, molecular evolutionary genetics analysis; ORF, open reading frame; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PRNP, prion protein gene; PrPc, cellular prion protein; PrPSc, proteinase-resistant form; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TSEs, transmissible spongiform encephalopathies; vCJD, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. AcknowledgmentsThe authors are thankful to Prof. Dr. Aris Haryanto, DVM, MSi, and Medania Purwaningrum, DVM, MSc, PhD, and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Universitas Gadjah Mada, for their support and for funding this research. The authors also thank Dr. Ir. Alek Ibrahim for the sample collection and the farmers who helped with this. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. FundingThis research was funded by Prof. Dr. Aris Haryanto, DVM., M.Si., and Medania Purwaningrum, DVM., M.Sc., Ph.D., Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada. Author contributionsArif Wicaksono was the principal author. He conducted the experiment, performed the laboratory investigation, and wrote the manuscript. Medania Purwaningrum was the principal supervisor. She funded the research, confirmed the results, and reviewed the final version of the manuscript. Aris Haryanto was a research supervisor and provided funding and resources for the research. Alek Ibrahim was a study supervisor. He provided resources, collected samples, and contributed to sample preparation. Anggita Suryandari and Rana Ayuningtyas Adhi Puspita contributed to sample preparation and assisted with the experiment. All authors provided critical feedback and helped to shape the research. Data availabilityThe data used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. ReferencesAcín, C., Martín-Burriel, I., Goldmann, W., Lyahyai, J., Monzón, M., Bolea, R., Smith, A., Rodellar, C., Badiola, J.J. and Zaragoza, P. 2004. Prion protein gene polymorphisms in healthy and scrapie-affected Spanish sheep. J. Gen. Virol. 85(7), 2103–2110. Adeola, A.C., Bello, S.F., Abdussamad, A.M., Mark, A.I., Sanke, O.J., Onoja, A.B., Nneji, L.M., Abdullahi, N., Olaogun, S.C., Rogo, L.D., Mangbon, G.F., Pedro, S.L., Hiinan, M.P., Mukhtar, M.M., Ibrahim, J., Saidu, H., Dawuda, P.M., Bala, R.K., Abdullahi, H.L., Salako, A.E., Kdidi, S., Yahyaoui, M.H. and Yin, T.T. 2023. Polymorphism of prion protein gene (PRNP) in Nigerian sheep. Prion. 17(1), 44–54. Alverson, J., Orourke, K.I. and Baszler, T.V. 2006. PrPSc accumulation in fetal cotyledons of scrapie resistant lambs is influenced by fetus location in the uterus. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 1035–1041. Baylis, M. and Goldmann, W. 2004. The genetics of scrapie in sheep and goats. Curr. Mol. Med. 4(4), 385–396. Bedi, J.S., Vijay, D. and Dhaka, P. 2022. Textbook of Zoonoses. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Belay, E.D. and Schonberger, L.B. 2005. The public health impact of prion diseases. Annu. Rev. Pub. Health. 26, 191–212. Bendheim, P.E., Brown, H.R., Rudelli, R.D., Scala, L.J., Goller, N.L., Wen, G.Y., Kascsak, R.J., Cashman, N.R. and Bolton, D.C. 1992. Nearly ubiquitous tissue distribution of the scrapie agent precursor protein. Neurology 42, 149–156. Benestad, S.L., Arsac, J.N., Goldmann, W. and Nöremark, M. 2008. Atypical/Nor98 scrapie: properties of the agent, genetics, and epidemiology. Vet. Res. 39(4), 19. Billinis, C., Psychas, V., Leontides, L., Spyrou, V., Argyroudis, S., Vlemmas, I., Leontides, S., Sklaviadis, T. and Papadopoulos, O. 2004. Prion protein gene polymorphisms in healthy and scrapie- affected sheep in Greece. J. Gen. Virol. 85(2), 547– 554. Brown, D.R., Clive, C. and Haswell, S.J. 2001. Antioxidant activity related to copper binding of native prion protein. J. Neurochem. 76, 69–76. Brown, D.R., Nicholas, R.S. and Canevari, L. 2002. Lack of prion protein results in a neuronal phenotype sensitive to stress. J. Neurosci. Res. 67, 211–224. Cassmann, E.D. and Greenlee, J.J. 2019. Pathogenesis, detection, and control of scrapie in sheep. AJVR. 81(7), 600–614. Chiarini, L.B., Freitas, A.R., Zanata, S.M., Brentani, R.R., Martins, V.R. and Linden, R. 2002. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO J. 21, 3317–3326. Curcio, L., Sebastiani, C., Di Lorenzo, P., Lasagna, E. and Biagetti, M. 2016. Review: a review on classical and atypical scrapie in caprine: Prion protein gene polymorphisms and their role in the disease. Animal. 10(10), 1585–1593. DeSilva, U., Guo, X., Kupfer, D.M., Fernando, S.C., Pillai, A.T.V., Najar, F.Z., So, S., Fitch, G.Q. and Roe, B.A. 2003. Allelic variants of ovine prion protein gene (PRNP) in Oklahoma sheep. Cytogenet. Genome. Res. 102, 89–94. Elsen, J.M., Amigues, Y., Schelcher, F., Ducrocq, V., Andréoletti, O., Eychenne, F., Tien Khang, J.V., Poivey, J.P., Lantier, F. and Laplanche, J.L. 1999. Genetic susceptibility and transmission factors in scrapie: detailed analysis of an epidemic in a closed flock of Romanov. Arch. Virol. 144, 431–445. Goldmann, W., O’Neill, G., Cheung, F., Charleson, F., Ford, P. and Hunter, N. 1999. PrP (prion) gene expression in sheep may be modulated by alternative polydenylation of its messenger RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 80(8), 2275–2283. Goldmann, W., Baylis, M., Chihota, C., Stevenson, E. and Hunter, N. 2005. Frequencies of PrP gene haplotypes in British sheep flocks and the implications for breeding programmes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98, 1294–1302. Goldmann, W. 2008. PrP Genetics in ruminant transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies. Vet. Res. 39(4), 1–14. Goldmann, W. 2018. Classic and atypical scrapie—a genetic perspective. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 153, 111–120. Gombojav, A., Ishiguro, N., Horiuchi, M. and Shinagawa, M. 2004. Unique amino acid polymorphisms of PrP genes in Mongolian Sheep breeds. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 66, 1293–1295. Haik, S. and Brandel, J.P. 2014. Infectious prion diseases in humans: cannibalism, iatrogenicity and zoonoses. Infec. Genet. Evol. 26, 303–312. Heaton, M.P., Leymaster, K.A., Freking, B.A., Hawk, D.A., Smith, T.P., Keele, J.W., Snelling, W.M., Fox, J.M., Chitko-McKown, C.G. and Laegrid, W.W. 2003. Prion gene sequence variation within diverse groups of US sheep, beef cattle and deer. Mamm. Genome. 14, 765–777. Heaton, M.P., Leymaster, K.A., Kalbfleisch, T.S., Freking, B.A., Smith, T.P., Clawson, M.L. and Laegreid, W.W. 2010. Ovine reference materials and assays for prion genetic testing. BMC Vet. Res. 6, 23. Igel-Egalon, A., Moudjou, M., Martin, D., Busley, A., Knapple, T., Herzog, L., Reine, F., Lepejova, N., Richard, C., Beringue, V. and Rezaei, H. 2017. Reversible unfolding of infectious prion assemblies reveals the existence of an oligomeric elementary brick. PLoS Pathog. 13(9), 1–21. Ikeda, T., Horiuchi, M., Ishiguro, N., Muramatsu, Y., Kai-Uwe, G.D. and Shinagawa, M. 1995. Amino acid polymorphisms of PrP with reference to onset of scrapie in Suffolk and Corriedale sheep in Japan. J. Gen. Virol. 76(10), 2577–2581. Jeffrey, M. and Gonzalez, L. 2007. Classical sheep transmissible spongiform encephalopathies: pathogenesis, pathological phenotypes and clinical disease. Neuropath. Appl. Neurobiol. 33, 373–394. Kdidi, S., Yahyaoui, M.H., Conte, M., Chiappini, B., Zaccaria, G., Ben Sassi, M., Ben Ammar El Gaaied, A., Khorchani, T. and Vaccari, G. 2014. PRNP polymorphisms in Tunisian sheep breeds. Livestock Sci. 167, 100–103. Klamt, F., Dal-Pizzol, F., Conte da Frota, M.L.J.R., Walz, R., Andrades, M.E., da Silva, E.G., Brentani, R.R., Izquierdo, I. and Fonseca Moreira, J.C. 2001. Imbalance of antioxidant defense in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30, 1137–1144. Lacroux, C., Corbiere, F., Tabouret, G., Lugan, S., Costes, P., Mathey, J., Delmas, J.M., Weisbecker, J.L., Foucras, G., Cassard, H., Elsen, J.M., Schelcher, F. and Andreoletti, O. 2007. Dynamics and genetics of PrPSc placental accumulation in sheep. J. Gen. Virol. 88, 1056–1061. Laegreid, W.W., Clawson, M.L., Heaton, M.P., Green, B.T., O’Rourke, K.I. and Knowles, D.P. 2008. Scrapie resistance in ARQ sheep. J. Virol. 82(20), 10318–10320. Lan, Z., Wang, Z.L., Liu, Y. and Zhang, X. 2006. Prion protein gene (PRNP) polymorphisms in Xinjiang local sheep breeds in China. Arch. Virol. 151, 2095–2101. Lan, X.Y., Zhao, H.Y., Li, Z.J., Li, A.M., Lei, C.Z., Chen, H. and Pan, C.Y. 2012. A novel 28-bp insertion-deletion polymorphism within goat PRNP gene and its association with production traits in Chinese native breeds. Genome 55(7), 547–552. Lan, Z., Li, J., Sun, C., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y., Chi, T., Yu, X., Song, F. and Wang, Z. 2014. Allelic variants of PRNP in 16 Chinese local sheep breeds. Arch. Virol. 159, 2141–2144. Li, J., Erdenee, S., Zhang, S., Wei, Z., Zhang, M., Jin, Y., Wu, H., Chen, H., Sun, X., Xu, H., Cai, Y. and Lan, X. 2018. Genetic effects of PRNP Gene Insertion/Deletion (InDel) on phenotypic traits in sheep. Prion 12(1), 42–53. Lühken, G., Buschmann, A., Brandt, H., Eiden, M., Groschup, M.H. and Erhardt, G. 2007. Epidemiological and genetical differences between classical and atypical scrapie cases. Vet. Res. 38(1), 65–80. Mabbott, N.A., Brown, K.L., Manson, J. and Bruce, M.E. 1997. T-lymphocyte activation and the cellular form of the prion protein. Immunology 92, 161–165. McBride, P.A., Eikelenboom, P., Kraal, G., Fraser, H. and Bruce, M.E. 1992. PrP protein is associated with follicular dendritic cells of spleens and lymph nodes in uninfected and scrapie-infected mice. J. Pathol. 168, 413–418. Oner, Y., Yesilbag, K., Tuncel, E. and Elmaci, C. 2011. Prion protein gene (PrP) polymorphisms in healthy sheep in Turkey. Animal. 5(11), 1728–1733. Pakpahan, S., Widayanti, R., Artama, W.T., Budisatria, I.G.S. and Luhken, G. 2023. Genetic variability of the Prion Protein Gene in Indonesian goat breeds. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 55(87), 1–7. Pammer, J., Weninger, W. and Tschachler, E. 1998. Human keratinocytes express cellular prion-related protein in vitro and during inflammatory skin diseases. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1353–1358. Prusiner, S.B. 1991. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 252, 1515–1522. Rashaydeh, F.S., Yildiz, M.A., Alharthi, A.S., Al- Baadani, H.H., Alhidary, I.A. and Meydan, H. 2023. Novel Prion Protein Gene Polymorphisms in Awassi Sheep in Three Regions of the Fertile Crescent. Vet. Sci. 10, 597. Saitoh, Y. and Mizusawa, H. 2024. Prion diseases, always a threat? J. Neurol. Sci. 463, 123119. Smith, P.G. and Bradley, R. 2003. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and its epidemiology. Br. Med. Bull. 66(1), 185–198. Stahl, N., Borchelt, D.R. and Prusiner, S.B. 1990. Differential release of cellular and scrapie prion proteins from cellular membranes by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Biochemistry. 29, 5405–5412. Teferedegn, E.Y., Yaman, Y. and Un, C. 2020. Five novel PRNP gene polymorphisms and their potential effect on Scrapie susceptibility in three native Ethiopian sheep breeds. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 122. Thorgeirsdottir, S., Sigurdarson, S., Thorisson, H.M., Georgsson, G. and Palsdottir, A. 1999. PrP gene polymorphism and natural scrapie in Icelandic sheep. J. Gen. Virol. 80(9), 2527–2534. Thumdee, P., Ponsuksili, S., Murani, E., Nganvongpanit, K., Gehrig, B., Tesfaye, D., Gilles, M., Hoelker, M., Jennen, D., Griese, J., Schellander, K and Wimmers, K. 2007. Expression of the prion protein gene (PRNP) and cellular prion protein (PrPc) in cattle and sheep fetuses and maternal tissues during pregnancy. Gene Expr. 13, 283–297. Tranulis, M.A. 2002. Influence of the Prion Protein Gene, Prnp, on scrapie susceptibility in sheep. APMIS. 110, 33–43. Vaccari, G., D’Agostino, C., Nonno, R., Rosone, F., Conte, M., Di Bari, M.A., Chiappini, B., Esposito, E., De Grossi, L., Giordani, F., Marcon, S., Morelli, L., Borroni, R. and Agrimi, U. 2007. Prion protein alleles showing a protective effect on the susceptibility of sheep to scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J. Virol. 81(13), 7306–7309. Vaccari, G., Scavia, G., Sala, M., Cosseddu, G., Chiappini, B., Conte, M., Esposito, E., Lorenzetti, R., Perfetti, G., Marconi, P., Scholl, F., Barbaro, K., Bella, A., Nonno, R. and Agrimi, U. 2009. Protective effect of the AT137RQ and ARQK176 PrP allele against classical scrapie in Sarda breed sheep. Vet. Res. 40(3), 19. van Keulen, L.J., Vromans, M.E., Dolstra, C.H., Bossers, A. and van Zijderveld, F.G. 2008. TSE pathogenesis in cattle and sheep. Vet. Res. 39, 24. Vitale, M., Migliore, S., Tilahun, B., Abdurahaman, M., Tolone, M., Sammarco, I., Presti, V.D.M.L. and Gebremedhin, E.Z. 2019. Two novel amino acid substitutions in highly conserved regions of prion protein (PrP) and a high frequency of a scrapie protective variant in native Ethiopian goats. BMC Vet. Res. 15(1), 128. Vitezica, Z.G., Beltran de Heredia, I. and Ugarte, E. 2013. Short communication: analysis of association between the prion protein (PRNP) locus and milk traits in Latxa dairy sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 96(9), 6079–6083. Yang, Q., Zhang, S., Liu, L., Cao, X., Lei, C., Qi, X., Lin, F., Qu, W., Qi, X., Liu, J., Wang, R., Chen, H. and Lan, X. 2016. Application of mathematical expectation (ME) strategy for detecting low frequency mutations: an example for evaluating 14-bp insertion/deletion (indel) within the bovine PRNP gene. Prion. 10(5), 409–419. Zhang, L., Li, N., Fan, B., Fang, M. and Xu, W. 2004. PRNP polymorphisms in Chinese ovine, caprine and bovine breeds. Anim. Genet. 35, 457–461. Zhang, J. and Zhang, Y. 2013. Molecular dynamics studies on 3D structures of the hydrophobic region PrP (109-136). Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin (Shanghai). 45(6), 509–519. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Wicaksono A, Haryanto A, Ibrahim A, Suryandari A, Puspita RAA, Purwaningrum M. Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 Web Style Wicaksono A, Haryanto A, Ibrahim A, Suryandari A, Puspita RAA, Purwaningrum M. Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=246941 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Wicaksono A, Haryanto A, Ibrahim A, Suryandari A, Puspita RAA, Purwaningrum M. Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Wicaksono A, Haryanto A, Ibrahim A, Suryandari A, Puspita RAA, Purwaningrum M. Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 Harvard Style Wicaksono, A., Haryanto, . A., Ibrahim, . A., Suryandari, . A., Puspita, . R. A. A. & Purwaningrum, . M. (2025) Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 Turabian Style Wicaksono, Arif, Aris Haryanto, Alek Ibrahim, Anggita Suryandari, Rana Ayuningtyas Adhi Puspita, and Medania Purwaningrum. 2025. Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 Chicago Style Wicaksono, Arif, Aris Haryanto, Alek Ibrahim, Anggita Suryandari, Rana Ayuningtyas Adhi Puspita, and Medania Purwaningrum. "Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Wicaksono, Arif, Aris Haryanto, Alek Ibrahim, Anggita Suryandari, Rana Ayuningtyas Adhi Puspita, and Medania Purwaningrum. "Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2789-2797. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Wicaksono, A., Haryanto, . A., Ibrahim, . A., Suryandari, . A., Puspita, . R. A. A. & Purwaningrum, . M. (2025) Genetic variability of the prion protein gene (PRNP) in thin-tailed and fat-tailed sheep. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2789-2797. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.47 |