| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2840-2848 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2840-2848 Short Communication A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)Iván Andrés Pineda-Betancurt and Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-Acuña, Fabian Alejandro Gömez-Torres**Corresponding Author: Fabian Alejandro Gómez-Torres. Department of Basic Sciences, School of Medicine, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia. Email: falegom [at] uis.edu.co Submitted: 18/03/2025 Revised: 18/03/2025 Accepted: 02/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

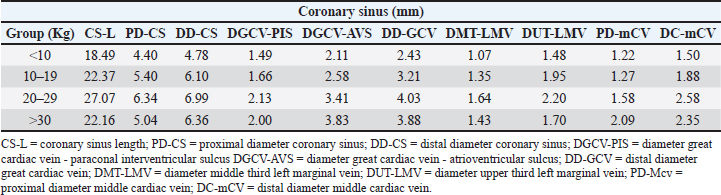

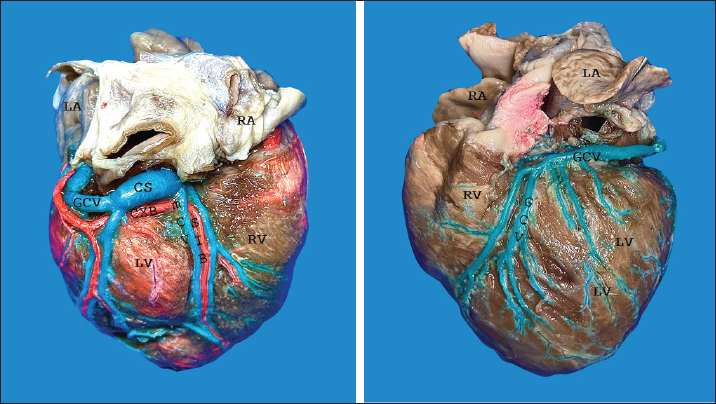

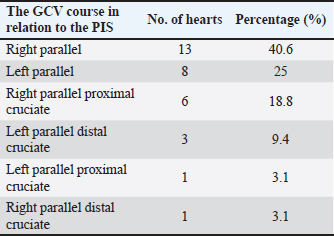

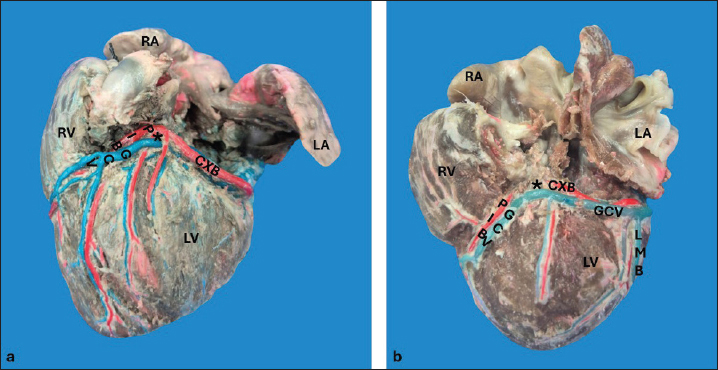

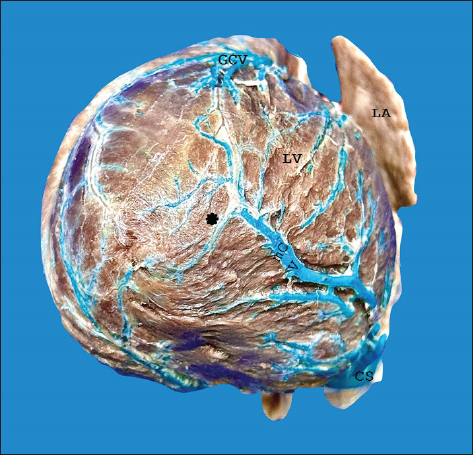

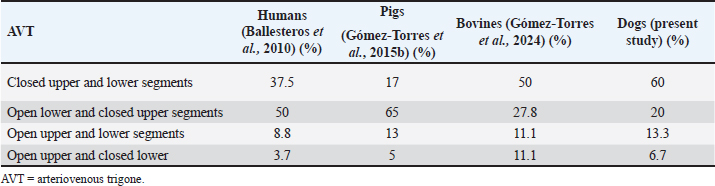

AbstractBackground: The inquiry on the venous drainage of the heart of dogs is still under development, despite its significant importance in the framework of comparative anatomy and its implications for veterinary medicine. Aim: The objective of the study was to perform a qualitative and biometric characterization of the cardiac veins of dogs. Methods: Using the venous bed perfusion technique, semi-synthetic resin (Palatal GP40L 80% and styrene 20% with blue dye) was injected into the venous system of 32 hearts of dogs that died in veterinary clinics, categorized by weight as follows: <10 kg; 10–19 kg; 20–29 kg; ≥30 Kg. Results: The length and diameter of the coronary sinus for the <10 kg group were 18.49 ± 3.31 and 4.40 ± 0.85 mm. Its morphology was cylindrical in 50% of cases and funnel-shaped in 34.4% of them. Arteriovenous trigone was observed in 93.8% of hearts, with a prevalence of closed configuration in 60% of cases, in both the superior and inferior segments. The diameter of the great cardiac vein at the level of the paraconal interventricular sulcus for the 20–29 kg group was 2.13 ± 0.49 mm, while its distal diameter was 4.03 ± 0.32 mm. The left marginal vein originated mainly in the lower third of the left margin (46.9%), and its caliber at the drainage (2.84 mm) was larger in cases at the level of the coronary sinus than in the great cardiac vein (p = 0.012). Venous anastomoses between the middle and great cardiac veins were observed in 50% of the hearts. Conclusion: The qualitative and biometric characteristics of the venous structures of the heart of dogs were described in detail and categorized by weight groups of the animals. These results are highly useful for the implementation of endovascular devices and the treatment of cardiac diseases. Keywords: Dogs, Cardiac veins, Coronary sinus, Great cardiac vein, Middle cardiac vein. List of abbreviationsANOVA: analysis of variance; CS: coronary sinus; GCV: great cardiac vein; LMV: left marginal vein; LAV: left azygos vein; AV: azygos vein; AVT: arteriovenous trigone; PIB: paraconal interventricular branch; CXB: circumflex branch; mCV: middle cardiac vein. IntroductionThe venous drainage of the heart of dogs is primarily managed by the coronary sinus (CS) and its tributary veins; it originates as a continuation of the great cardiac vein (GCV) and receives this designation when the GCV joins the oblique vein of the left atrium (Lafontant et al., 1962). At the level of the transition from GCV to CS, the presence of a thin, double internal valve can be observed; whose concavity prevents reflux during atrial systole (Piffer et al., 1994). The posterior veins of the left ventricle drain into the CS together with the left marginal veins, although the latter with a lesser occurrence. Furthermore, the CS drains into the right atrium, situated in the most posterior part of the interatrial septum; and in most cases, it lacks a valve (98.3%); while occasionally (1.7%) presents a thick semilunar valve with a free and concave border of variable length (Genain et al., 2018). Same as in humans, pigs, and bovines, the CS in dogs is located in the left atrioventricular sulcus; this structure and its tributaries drain most of the blood from the heart into the right atrium. In bovine and human hearts, the CS receives drainage from the GCV and the left marginal vein (LMV); while in pigs, the left azygos vein (LAV) is additionally involved (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015a; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). Recent studies of comparative anatomy and angiography of the coronary venous system have shown that blood flow between humans, dogs, sheep, and pigs is similar (Genain et al., 2018). In humans and dogs, the azygos vein (AV) drains into the superior (cranial) vena cava, whereas in sheep, and pigs the LAV drains directly into the CS (Gómez-Torres et al., 2018). The CS in dogs is partially covered by the left atrium and, has a length of 2–6.5 cm (Piffer et al., 1994; Esperança Pina et al., 2008; Genain et al., 2018) and a diameter of 5.5 mm (Genain et al., 2018). In humans, the CS’s length varies immensely (2.7–5.4 cm), with a diameter ranging from 6.8 to 9 mm and, a variable morphology (cylindrical, flattened, or funnel-shaped). The CS drains into the right atrium, and its ostium is located between the opening of the inferior vena cava and the right atrioventricular orifice (Mahmud et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2006). Meanwhile, in bovines, the CS has a length of 42.2 mm, a proximal diameter of 12.5 mm, and a distal diameter of 13.8 mm (Gómez-Torres et al., 2024); whereas in pigs, the reported length is 26.9 mm, with proximal and distal diameters of 10.8 mm and 11.9 mm, respectively (Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b). In humans, pigs, bovines, and dogs, GCV has been described as originating from the cardiac apex, and at the level of the proximal segment of the paraconal interventricular sulcus (PIS), it extends to the left, reaching the atrioventricular sulcus. Here, it forms the arteriovenous trigone (AVT) with the paraconal interventricular branch (PIB) (anterior in humans) and the circumflex branch (CXB); then, after a short course through the atrioventricular sulcus, it dilates abruptly and gives rise to the CS (Nakazawa et al., 1978; Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015a; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). The configuration of different AVT expressions has been reported, with evident differences in humans, pigs, and bovines (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). This anatomical finding has not been reported quantitatively in dogs. In dogs, similar to what has been reported in bovines and pigs (Di Guglielmo et al., 1960; Genain et al., 2018), the middle cardiac vein (mCV) originates from the cardiac apex, courses through the subsinusal interventricular sulcus, and drains into the CS, near its drainage into the right atrium (Gómez-Torres et al., 2015a; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024); in humans, it originates in similar percentages both from the lower third of the anterior ventricular surface and the apex, mostly draining (83%) into the distal segment of the CS (Ballesteros et al., 2010). The LMV in dogs courses along the lateral border of the left ventricle and drains into the GCV or directly into the CS (Genain et al., 2018). In humans, the LMV originates from the pulmonary surface, primarily in the middle third (46.9%), and in most cases (95.3%), it drains into the GCV (Ballesteros et al., 2010). In bovines, the LMV originates from the lower third of the left cardiac margin (53.6%) and drains into the GCV (Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). In pigs, this vessel originates from the cardiac apex and, similar to humans and bovines, drains into the distal end of the GCV (Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b). The venous anastomoses reported in dogs are primarily located at the cardia apex level, involving the proximal segments of the GCV and mCV in all cases. The anastomoses may be single or double, whereas the anastomoses between the GCV and the LMV are less frequent (10%) (Pakalska and Kolff, 1980; Genain et al., 2018). Despite the significant relevance that the clinical treatment of domestic dogs has gained in the field of cardiology in recent decades, due to their status as animal companions and the recognition as a viable experimental model, there is a lack of qualitative and biometric information about the characteristics of the venous drainage system of this species. Previous studies have not yet provided a detailed description of the courses, typologies, dimensions, and diameters of the coronary venous system of dogs, alongside its variations. As a result, procedures such as venous angiography and endovascular interventions for congenital or degenerative heart diseases are still in development (Scansen, 2018). The objective of this study was to evaluate the qualitative and morphometric characteristics of the CS and its tributaries in dogs of different weights through the perfusion of their venous beds with polyester resin. Materials and MethodsThis cross-sectional study was conducted on 32 hearts of dogs that died of natural causes in veterinary clinics in Bucaramanga–Colombia. The sample included dogs of different ages and weights; although dogs that had been diagnosed with heart disease or cardiac trauma, as well as those that underwent euthanasia, were excluded due to their possible association with a primary or secondary terminal heart disease. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Industrial de Santander (Acta 5–2024) and complies with Act 84 of 1989 at the national level, specifically Chapter VI of “Estatuto Nacional para la Protección de los Animales”, about the use of animals in experimentation and research. The evaluated sample was classified into different categories: <10 kg (n = 14), 10–19 kg (n = 13), 20–29 kg (n = 3), and ≤30 Kg (n = 2). The heart specimens were obtained along with the pericardial sac and main vessels to preserve the integrity of the coronary vasculature. These pieces were kept frozen (–18°C) until the injection procedure of the vascular beds. A washing and exsanguination process was carried out for six hours. A silk plicature was conducted around the opening of the CS. A semi-synthetic resin, composed of 80% Palatal GP40L and 20% styrene, mixed with blue mineral dye, was injected into the blood vessel. Subsequently, the samples were preserved in 10% formaldehyde solution for 96 hours. The subepicardial adipose tissue adjacent to the cardiac venous beds was removed using a 15% KOH solution. Consequently, the CS and its tributaries were dissected from their origins to their distal segments. Courses, morphologies, diameters, anastomoses, and the presence of anatomical variations were recorded. The specific configuration of the AVT was documented, while considering the relationship between the GCV, the PIB, and the CXB, according to Pejkovic and Bogdanovic’s criteria (Pejkovic and Bogdanovic, 1992), as follows: open superior and inferior, closed superior and inferior, open inferior closed superior, and open superior closed inferior. The external diameters of these vessels were measured at 0.5 mm from their origin using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo®). Digital photographic records of the venous structures of each evaluated specimen were obtained. The prevailing veterinary anatomical nomenclature was followed (2017). The descriptive data analysis was conducted using SPSS 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Microsoft Excel 2013. The 95% CI was calculated. For each morphometric measurement, descriptive statistical parameters were calculated, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to assess the normality of the samples. In the case of quantitative variables, Student’s t-test was used to compare two independent groups. When quantitative variables showed a regular distribution among groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. The results were expressed in average terms and standard deviations for all analyzed dimensions and lengths. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. ResultsThe weight of all 32 hearts for the groups <10 kg, 10– 19 kg, 20–29 kg, and ≤30 Kg was recorded as 63.21 g, 100.77 g, 141.67 g, and 175.00 g, respectively. The CS for the < 10 kg group had a length of 18.49 ± 3.31 mm and a proximal diameter of 4.40 ± 0.85 mm (Table 1); it presented a cylindrical morphology in 16 (50%) cases (Fig. 1a), funnel-shaped in 11 (34.4%) specimens, and flattened in 5 cases (15.6%) specimens. No significant differences were observed between calibers at the beginning of the CS and at their drainage (p = 0.088). The origin of the GCV was observed at the apex in 27 specimens (84.4%) (Fig. 1b) and, in the lower third of the PIS in 5 hearts (15.6%). The GCV showed a right-parallel course relative to the PIS in 13 hearts (40.6%) (Table 2). The diameter of this blood vessel at the PIS level in the 20–29 kg group was 2.13 ± 0.49 mm, and at the left atrioventricular sulcus, it measured 3.41 ± 0.90 mm, while its distal diameter at the CS drainage level was 4.03 ± 0.32 mm (Table 1). The presence of AVT was observed in 30 hearts (93.8%), with a prevalence of the closed configuration in the superior and inferior segments in 18 cases (60%) (Fig. 2a), followed by the open configuration in the inferior segment and closed in the superior segment in 6 hearts (20%) (Fig. 2b). With less predominance, the open configuration in the upper third and closed configuration in the lower third was observed in 4 cases (13.3%) (Fig. 3a); and for the 2 remaining cases (6.7%) in a lesser extent, the open configuration in the superior and inferior segments (Fig. 3b). The GCV had a superficial course relative to the PIB in 28 cases (92.3%) and a deep course in 2 cases (7.7%). Table 1. Diameter of cardiac veins in dogs.

Fig. 1. Right surface of the heart (a). Left surface of the heart (b). CS = coronary sinus; mCV = middle cardiac vein; GCV = great cardiac vein; CXB = circumflex branch; SIB = subsinusal interventricular branch; RA = right atrium; LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle. Table 2. Course of the greater cardiac vein in relation to the paraconal interventricular sulcus in dogs.

Fig. 2. Left surface of the heart. Closed configuration of the arteriovenous trigone in the upper and lower segments (a), open in the lower segment, and closed in the upper segment (b). (*): arteriovenous trigone; GCV = great cardiac vein; PIB = paraconal interventricular branch; CXB = circumflex branch; Arrow = sinoatrial node branch; RA = right atrium; LA = left atrium; RV = right ventricle; LV = left ventricle.

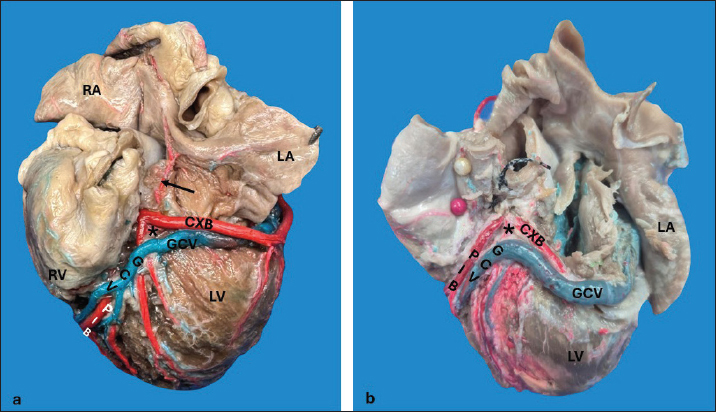

Fig. 3. Left surface of the heart. Closed configuration of the arteriovenous trigone in the lower segment, open in the upper segment (a), and open in the upper and lower segments (b). (*): arteriovenous trigone; GCV = great cardiac vein; LMB = left marginal branch; PIB = paraconal interventricular branch; CXB = circumflex branch; RA = right atrium; LA = left atrium; RV = right ventricle; LV = left ventricle. The LMV was observed in all hearts (Fig. 3b); in 15 cases (46.9%), it originated from the lower third of the left cardiac margin, at the apex in 11 specimens (34.4%), and in the middle third of the obtuse margin in 6 cases (18.8%). In the 20–29 kg group, the LMV had a diameter of 2.20 ± 0.36 mm in the upper third (Table 1). The LMV in 19 cases (59.4%) drained into the GCV, in 10 specimens (31.3%) at the level of the GCV transitioning into the CS, and in 3 hearts (9.4%) directly into the CS. The distal caliber of the LMV was significantly larger in cases in which this vessel drained into the CS compared with veins draining into the GCV (p = 0.012). The origin of the mCV was observed at the apex in 27 hearts (84.4%) (Fig. 1a), in the lower third in 3 specimens (9.4%), in the middle third in 1 heart (3.1%), and in the upper third in 1 case (3.1%). In the 10–19 kg group, the proximal and distal diameters of this blood vessel were 1.27 ± 0.40 mm and 1.88 ± 0.60 mm, respectively (Table 1). In all samples, the mCV was drained into the CS. Anastomosis was observed in 16 hearts (50%) (Fig. 4), occurring between the mCV and the GCV in 15 specimens (93.8%), whereas in a single case (6.2%), the mCV anastomosed with both the GCV and the left posterior ventricular vein.

Fig. 4. Anastomosis between the tributaries of the mCV and the GCV at the cardiac apex (*). LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle. DiscussionIn this study, repletion of the coronary venous beds in dogs, variability in the course, diameters, and tributaries of the CS were observed, findings consistent with previous studies conducted in humans, bovines, and pigs (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015a; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). In humans, pigs, and dogs, the cylindrical shape has been reported as the predominant anatomical expression of the CS (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez- Torres et al., 2015b; Genain et al., 2018); these findings are consistent with those observed in our study. The length of the CS is described within a range of 2–6.5 cm, and a diameter of 5.5–10 mm (Esperança et al., 1981; Piffer et al., 1994; Genain et al., 2018), findings that are slightly larger than those observed in the 20–29 kg group (Table 1). However, compiling our records across different weight groups allows us to present more detailed and useful information when it comes to determining the significance of these structures, particularly when the species is considered as an experimental model or a model for the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac disease. The diameter of the GCV (2.23 mm) at the level of the PIS in the 20–29 kg group observed in our study was slightly larger than that recorded in dogs (1.5 mm) of a similar weight (Genain et al., 2018). There are no reports on other weight groups. This blood vessel coursed along the PIS with its corresponding arterial branch and originated predominantly (85.7%) at the apex, a percentage higher than that reported in humans (57.4%), bovines (78.6%), and pigs (76%) (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b; Gómez- Torres et al., 2024). In humans, the presence of AVT has been reported in 58.8%–89% of cases; in bovines, it has been observed in 64.3% (Ortale et al., 2001; Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024), while in pigs, it has been reported in 97.5% (Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b), a finding consistent with our observation (93.8%). In our study on dogs, we observed a predominance of the closed configuration in both the superior and inferior segments (60%), similar to bovines, but with a lower incidence (50%) (Gómez- Torres et al., 2024). In contrast, in humans (50%) and pigs (65%), the most frequent configuration is open for the inferior segment and closed for the superior segment (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b). This configuration of the AVT allowed us to observe that in the species with right coronary dominance, the configuration was mainly open in the lower segment and closed in the upper segment; in contrast to the species with left coronary dominance, where the AVT was closed in both the upper and lower segments (Table 3). The clinical significance of the configuration of this structure in dogs lies in its use for interventional procedures, such as radiofrequency catheter ablation (Santilli et al., 2006). In this procedure, among the various special placements of the electrocatheters, one of them, the decapolar catheter, after being guided through the introducer via the jugular vein, is positioned from the CS to the GCV (Santilli et al., 2014, 2010). This procedure is commonly used in patients with tachyarrhythmias resulting from congenital abnormalities, such as accessory ventricular or bypass pathways (Wright et al., 2018; Stern and Ueda, 2019; Hsue et al., 2022). Additionally, the use of this procedure in diseases such as arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, which has been described in English Bulldogs, Boxers, and humans, may lead to sudden death (Meurs et al., 1999; Noszczyk-Nowak et al., 2010; Vischer et al., 2017; Cunningham et al., 2018; ; Crooks et al., 2022). In our study on dogs, the origin of the LMV was most frequently observed (46.9%) in the lower third of the left cardiac border, consistent with what has been reported in bovines (Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). In contrast, in pigs (30%) and humans (46.9%), the predominant origin of this vascular structure was in the middle third of the same border (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015a). In humans, LMV drainage has been reported in the GCV (95.3%) (Ballesteros et al., 2010), in bovines (76.9%), and in pigs (97%), into the distal end of the GCV (Gómez- Torres et al., 2015b; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). In our findings in dogs, this structure drained into the GCV in 59.4% of the cases, in agreement with (Genain et al., 2018). Table 3. Configuration of the AVT in different species expressed as a percentage.

In accordance with previous reports in humans, bovines, and pigs, the mCV was observed in all specimens (Ortale et al., 2001; Ballesteros et al., 2010; Genain et al., 2018; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). We described its origin in dogs primarily at the apex, consistent with findings in bovines and pigs (Gómez-Torres et al., 2015a; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024); whereas in humans, the mCV mainly originates in the lower third of the anterior ventricular surface (Ballesteros et al., 2010). In the evaluated species, in agreement with what has been described in humans, pigs, and bovines, the mCV drains into the CS (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez-Torres et al., 2015b; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). However, it has also been reported that in humans, the mCV may drain directly into the right atrium in 15%–20% of cases (Adachi, 1933; Duda and Grzybiak, 1998; Melo et al., 1998). Anastomoses between the main branches of the cardiac venous system are morphological features of many mammals. In humans, bovines, and pigs, anastomoses between the mCV and GCV have been reported in 58.8–63% of cases (Ballesteros et al., 2010; Gómez- Torres et al., 2015a; Gómez-Torres et al., 2024). In our series, we observed these venous connections in 50% of specimens, which is lower than what has been described by angiographic studies in dogs, where they were found in all cases (Genain et al., 2018). The latter study also reported microvascular anastomoses located within the myocardial thickness. The presence of anastomoses, particularly between the veins that drain the paraconal and subsinusal segments of the heart, facilitates the overall venous drainage into the right atrium; particularly in scenarios where one segment may be obstructed, the presence of anastomoses will aid in draining the affected area. ConclusionThe qualitative and biometric characteristics of the venous structures of the heart of dogs were described in detail, providing valuable information for the implementation of endovascular device applications, as these measurements were categorized by animal weight groups. Given the importance of venous intervention in managing arrhythmic processes through radiofrequency catheter ablation, the heart’s AVT, which was previously undescribed in dogs, was qualitatively characterized. This research’s findings not only expand existing knowledge of the venous drainage of the heart of dogs, within the framework of comparative anatomy, and may also be useful for clinical applications in the diagnosis, management, and treatment of cardiac diseases. AcknowledgmentsSpecial thanks to the veterinary clinics in the city of Bucaramanga, Colombia, for their dedication in providing samples for the development of the study. FundingNone. Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. Authors contributionThis research was conceptualized by Fabian Gómez- Torres and Luis Ballesteros-Acuña. Injections of the vascular beds of the hearts and cleaning were performed by all authors. The photographs were taken by Iván Andrés Pineda-Betancurt. All authors contributed to the manuscript’s reading, reviewing, revising, and approving the final version. Data availabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript. ReferencesAdachi, B. 1933. Das venensystem der Japaner, Vv. Cordis. In: Adachi B (ed). Tokyo: Druckanstalt Kenkyusha. pp: 41–64. Ballesteros, L.E., Ramírez, L.M. and Forero, P.L. 2010. Estudio del seno coronario y sus tributarias en individuos colombianos. Rev. Colomb. Cardiol. 17, 9–15. Crooks, A.V., Hsue, W., Tschabrunn, C.M. and Gelzer, A.R. 2022. Feasibility of electroanatomic mapping and radiofrequency catheter ablation in Boxer dogs with symptomatic ventricular tachycardia. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 36, 886–896. Cunningham, S.M., Sweeney, J.T., MacGregor, J., Barton, B.A. and Rush, J.E. 2018. Clinical features of english bulldogs with presumed arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: 31 cases (2001–2013). J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 54, 95–102. Di Guglielmo, L., Baldrighi, V., Montemartini, C., Schifino, A., 1960. Roentgen investigation of the coronary veins in the dog. Acta Radiol. 53, 191–200. Duda, B. and Grzybiak, M. 1998. Main tributaries of the coronary sinus in the adult human heart. Folia Morphol. 57, 363–369. EsperanÇa Pina, J.A., Correia, M., O’Neill, G. and Rendas, B. 2008. Morphology of the veins draining the coronary sinus of the dog. Acta Anat. 109, 122–128. Genain, M.-A., Morlet, A., Herrtage, M., Muresian, H., Anselme, F., Latremouille, C., Laborde, F., Behr, L. and Borenstein, N. 2018. Comparative anatomy and angiography of the cardiac coronary venous system in four species: human, ovine, porcine, and canine. J. Vet. Cardiol. 20, 33–44. Gómez-Torres, F.A., Ballesteros, L.E. and Estupiñan, H.Y. 2018. Morphological characterization of the coronary sinus and its tributaries in short hair sheep. Comparative analysis with the veins in humans and pigs. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 123, 81–90. Gómez-Torres, F.A., Cortés-Machado, L.S. and Ballesteros-Acuña, L.E. 2024. Anatomical study of the cardiac veins and their tributaries in bovines (Bos indicus) in comparison VB with humans and other animal species. Int. J. Morphol. 42, 52–58. Gómez-Torres, F.A., Ballesteros, L.E. and Cortes, L.S. 2015a. Morphological expression of the pig coronary sinus and its tributaries: a comparative analysis with the human heart. Eur. J. Anat. 19, 139–144. Gómez-Torres, F.A., Ballesteros, L.E. and Stella Cortés, L. 2015b. Morphological description of great cardiac vein in pigs compared to human hearts. Rev. Bras. Cir. Cardiovasc. órgão. 30, 63–69. Hsue, W., Huh, T., Gelzer, A.R. and Tschabrunn, C.M. 2022. Three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping and radiofrequency catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmia in a dog without structural heart disease. J. Vet. Cardiol. 39, 14–21. Lafontant, R.R., Feinberg, H. and Katz, L.N. 1962. Partition of coronary flow and cardiac oxygen extraction between coronary sinus and other coronary drainage channels. Circ. Res. 11, 686–698. Lee, M.S., Shah, A.P., Dang, N., Berman, D., Forrester, J., Shah, P.K., Aragon, J., Jamal, F. and Makkar, R.R. 2006. Coronary sinus is dilated and outwardly displaced in patients with mitral regurgitation: quantitative angiographic analysis. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 67, 490–494. Mahmud, E., Raisinghani, A., Keramati, S., Auger, W., Blanchard, D.G. and DeMaria, A.N. 2001. Dilation of the coronary sinus on echocardiogram: prevalence and significance in patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 14, 44–49. Melo, W.D., Prudencio, L.A., Kusnir, C.E., Pereira, A.L., Marques, V., Vieira, M.C. and de Paola, A.A. 1998. Angiography of the coronary venous system. Use in clinical electrophysiology. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 70, 409–413. Meurs, K.M., Spier, A.W., Miller, M.W., Lehmkuhl, L. and Towbin, J.A. 1999. Familial ventricular arrhythmias in boxers. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 13, 437–439. Nakazawa, H.K., Roberts, D.L. and Klocke, F.J. 1978. Quantitation of anterior descending vs. circumflex venous drainage in the canine great cardiac vein and coronary sinus. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 234, H163–H166. Noszczyk-Nowak, A., Skoczyński, P. and Gajek, J. 2010. Tachycardiomyopathy in Human and Animals. Pathophysiol. Treat. Progn. 19, 245–249. Ortale, J.R., Gabriel, E.A., Iost, C. and Márquez, C.Q. 2001. The anatomy of the coronary sinus and its tributaries. Surg. Radiol. Anat. SRA 23, 15–21. Pakalska, E. and Kolff, W.J. 1980. Anatomical basis for retrograde coronary vein perfusion. Venous anatomy and veno-venous anastomoses in the hearts of humans and some animals. Minn. Med. 63, 795–801. Pejkovic, B. and Bogdanovic, D. 1992. The great cardiac vein. Surg. Radiol. Anat. SRA 14, 23–28. Piffer, C.R., Piffer, M.I.S., Santi, F.P. and Dayoub, M.C.O. 1994. Anatomic observations of the coronary sinus in the dog (Canis familiaris). Anat. Histol. Embryol. 23, 301–308. Santilli, R.A., Perego, M., Perini, A., Carli, A., Moretti, P. and Spadacini, G. 2010. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of cavo-tricuspid isthmus as treatment of atrial flutter in two dogs. J. Vet. Cardiol. 12, 59–66. Santilli, R.A., Ramera, L., Perego, M., Moretti, P. and Spadacini, G. 2014. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of atypical atrial flutter in dogs. J. Vet. Cardiol. 16, 9–17. Santilli, R.A., Spadacini, G., Moretti, P., Perego, M., Perini, A., Tarducci, A., Crosara, S. and Salerno-Uriarte, J.A. 2006. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of concealed accessory pathways in two dogs with symptomatic atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia. J. Vet. Cardiol. 8, 157–165. Scansen, B.A. 2018. Cardiac interventions in small animals: areas of uncertainty. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 48, 797–817. Stern, J.A. and Ueda, Y. 2019. Inherited cardiomyopathies in veterinary medicine. Pflugers Arch. 471, 745–753. Vischer, A.S., Connolly, D.J., Coats, C.J., Fuentes, V.L., McKenna, W.J., Castelletti, S. and Pantazis, A.A. 2017. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in Boxer dogs: the diagnosis as a link to the human disease. Acta Myol. Myopathies Cardiomyopath. 36, 135–150. Wright, K.N., Connor, C.E., Irvin, H.M., Knilans, T.K., Webber, D. and Kass, P.H. 2018. Atrioventricular accessory pathways in 89 dogs: Clinical features and outcome after radiofrequency catheter ablation. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 32, 1517–1529. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 Web Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=248169 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 Harvard Style Pineda-betancurt, I. A., Ballesteros-acuña, . L. E. & Gómez-torres, . F. A. (2025) A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 Turabian Style Pineda-betancurt, Iván Andrés, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-acuña, and Fabian Alejandro Gómez-torres. 2025. A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 Chicago Style Pineda-betancurt, Iván Andrés, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-acuña, and Fabian Alejandro Gómez-torres. " A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Pineda-betancurt, Iván Andrés, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-acuña, and Fabian Alejandro Gómez-torres. " A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2840-2848. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Pineda-betancurt, I. A., Ballesteros-acuña, . L. E. & Gómez-torres, . F. A. (2025) A direct anatomical characterization of the coronary sinus in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2840-2848. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.53 |