| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(10): 5326-5334 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(10): 5326-5334 Research Article Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattleJatuporn Kajaysri* and Apiradee IntarapukDepartment of Science, Technology and Innovation, Faculty of Science, Chulabhorn Royal Academy, Bangkok, Thailand *Corresponding Author: Jatuporn Kajaysri. Department of Science, Technology and Innovation, Faculty of Science, Chulabhorn Royal Academy, Bangkok, Thailand. Email: jatuporn.kaj [at] cra.ac.th Submitted: 22/04/2025 Revised: 27/08/2025 Accepted: 11/09/2025 Published: 31/10/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

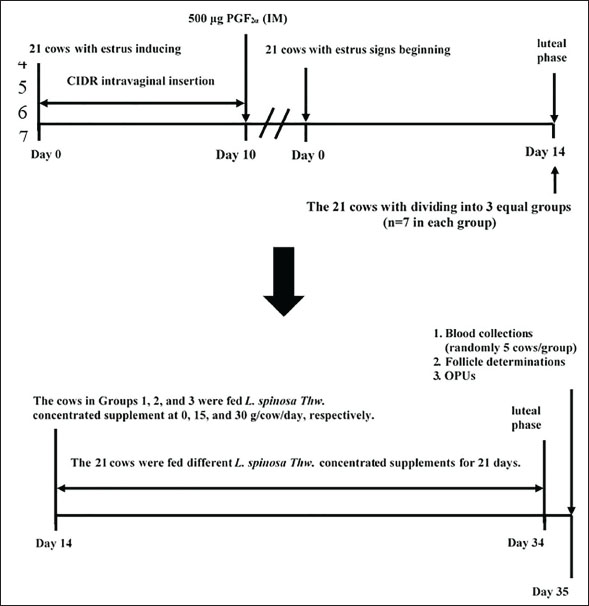

AbstractBackground: Treating beef cattle with estradiol benzoate before ovum pick-up (OPU) increases the number of high-quality follicles and oocytes. L. spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplement has been used to replace synthetic estradiol benzoate in food animals to reduce the side effects and meat residue in consumers. Aim: This study aimed to evaluate the effects of L. spinosa Thw. feed supplementation on the follicle and oocyte quality of crossbred Brahman cattle. Methods: Estrus was induced in 21 crossbred Brahman cows using intravaginal controlled internal drug release (CIDR) and prostaglandin F22α. The cows were divided into Groups 1, 2, and 3, with each group receiving L. spinosa Thw. supplements at daily rates of 0, 15, and 30 g per cow, respectively. Blood samples were collected to measure plasma estradiol (E2) levels. The follicles were evaluated via ultrasonography and categorized according to follicle diameter. Oocytes were collected using OPUs for counting and grading. Results: The cows in Groups 2 and 3 produced more medium follicles (Group 2=5.29 ± 1.80, Group 3=7.43 ± 1.72) than those in Group 1 (2.57 ± 1.51) (p < 0.05). Cows in Group 3 also produced more combined grade A+B (good-quality) oocytes (9.71 ± 1.89) than Group 1’s (5.14 ± 2.12) (p < 0.05). Groups 1 and 2 did not differ significantly in this regard, nor did Group 2 differ from Group 3. In addition, the plasma E2 levels of Groups 2 and 3 were not significantly different, and both groups showed higher levels than those in Group 1 (p < 0.05). Conclusion: Feeding crossbred Brahman with 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. was more effective than the control group, resulting in a greater number of high-quality follicles and oocytes. Keywords: Animal feed supplement, Brahman cow, L. spinosa Thw., Phytoestrogen, OPU. IntroductionOvum pick-up (OPU) involves aspirating oocytes from follicles in the donor’s ovaries by needle ultrasound-guided follicular puncture with vacuum suction. In vitro production (IVP) employs the collected oocytes obtained during OPU (Numabe et al., 2001; Fry, 2020; Baruselli et al., 2021; Ferré et al., 2023). Currently, OPU plays a significant role in improving the effectiveness of in vitro fertilization (IVF) (Numabe et al., 2001) and embryo transfer (Galli et al., 2001). Additionally, OPU enables the harvesting of genetically superior oocytes from living cattle (Galli et al., 2014; Crowe et al., 2021; Balboula et al., 2022). This method allows oocytes to be assembled during various estrous stages and even in the early stages of pregnancy without the need for donor cows to be in a typical estrous cycle. In addition, the ovaries of prepubertal heifers, juvenile calves, and cows with reproductive issues might yield oocytes (Looney et al., 1994; Majerus et al., 1999; Taneja et al., 2000; Galli et al., 2001). By collecting oocytes from females as early as prepubescence, the number of oocytes per female can be increased in acyclic or pregnant cows, those with genital tract infections or obstructed fallopian tubes, or those that do not respond to superovulation. Genetic variation can be increased by fertilizing collected oocytes in vitro with sperm from various bulls (Merton et al., 2003). Therefore, OPU-IVP can quickly improve cattle genetics by reducing intergenerational intervals and enhancing the selection capacity of desired genotypes (Doublet et al., 2020). Consequently, the demand for OPU-IVP embryos in the cattle production industry is anticipated to increase (Merton et al., 2003; Faber et al., 2003; Egashira et al., 2019). The American Embryo Transfer Association reports that 2 million oocytes have been recovered for use in embryo transfer from 122,431 OPU procedures (Demetrio et al., 2020). OPU can be either prestimulatory or nonstimulatory. Previously, unstimulated animals were used for OPU. However, in recent years, hormonal stimulation in animals has become more common, increasing oocyte retrieval. The pre-stimulatory protocols employed for ovarian function enhancement before OPU treatment in cattle are based on the efficacy of various exogenous reproductive hormones. During OPU collection, Japanese Black cattle receiving exogenous estradiol benzoate (EB) at the luteal phase before OPU produced more medium-sized follicles and high-quality oocytes than those not receiving EB therapy at the same phase (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). A typical approach for obtaining oocytes developed in vivo using OPU in Japanese Black cattle involves the use of EB, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Egashira et al., 2019). Mature oocytes are super-stimulated using GnRH and FSH therapies and subsequently used to produce high-quality in vitro embryos (Egashira et al., 2019). However, exogenous EB treatment has been found to inhibit the dominant follicle regardless of the developmental stage, consistently triggering a new follicular wave on average 4.3 days later (Bo et al., 1995; Araujo et al., 2009). In contrast, OPU without previous hormonal therapy can be completed and repeated in 1–3 weeks (Kruip et al., 1994), but fewer high-quality oocytes are harvested than in OPU with prior EB treatment (Hidaka et al., 2018). Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.), a perennial herb native to the family Araceae, is widespread throughout Asia’s tropical and subtropical regions (Hong Van et al., 2006). All year round, it grows in wetlands, ditches, muddy streams, open marshes, subtropical woods, wet forests, and areas with standing water (Kankanamge et al., 2017). In Thailand, it is known as Phak Naam, meaning it can grow in terrestrial or aquatic habitats. It is short-stemmed and spiny with an underground rhizome, allowing it to grow and spread. The leaves and rhizomes of L. spinosa Thw. are consumed as vegetables and used as perennial herbs in traditional medicine to treat various diseases (Kaewamatawong et al., 2013). L. spinosa Thw. is a natural source of phytoestrogens and phytoandrogens; the rhizome, leaves, and roots are rich in testosterone and estrogen (Suthikrai et al., 2007). Remarkably, concentrated dry L. spinosa Thw. powder has been used as a feed supplement to increase the growth rate of cattle and buffaloes (Suthikrai et al., 2007; Jintana et al., 2013). Estradiol (E2) levels in leaves and roots were recently reported to be 10.76 and 14.55 pg/g dry weight, respectively (Suthikrai et al., 2007). There has been no report of toxicity in L. spinosa Thw., although it is widely used in Thai veterinary medicine (Kaewamatawong et al., 2013). The roots of L. spinosa Thw. contain a high concentration of phytoestrogens, which were fed to enhance the growth rate of cattle. Additionally, these phytoestrogens exhibited properties similar to those of EB. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that incorporating phytoestrogens (natural E2) in the form of dried root powder from L. spinosa Thw. as a dietary supplement could effectively boost the number of medium-sized follicles before and high-quality oocytes after OPUs, serving as an alternative for EB treatment. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy of L. spinosa Thw. supplementation in enhancing ovarian function capacity before OPU in relation to changes in plasma E2 levels and oocyte number in crossbred Brahman cattle. Materials and MethodsStudy duration and locationFrom March to October 2021, a private beef farm in Kanchanaburi Province (western region), Thailand, hosted this study, which included follicle examination and aspiration and oocyte evaluation. Experimental animalsThis study used 21 primiparous or pluriparous crossbred Brahman cows. The cows were 3–8 years old, weighed approximately 300–450 kg each, and were housed in open-stall barns. The cows were fed concentrates containing 14% crude protein and grass silage regularly and were provided with ad libitum access to clean water. They lived and could walk freely in the barns throughout the experiment. The temperature and humidity in the stall barns were 27°C–32°C and 65%–85%, respectively. All cows were healthy and cycling; their reproductive organs were normal, and no anatomical reproductive disorders were observed. The cows were routinely dewormed and received annual vaccinations to avoid disease in compliance with the immunization schedule of the Department of Livestock Development of Thailand. Experimental designEstrus was induced in all 21 cows by intravaginal CIDR of 1.9 g progesterone (Eazi-Breed®, Pfizer Animal Health Co., Ltd, Hamilton, New Zealand) for 10 days and 500 µg prostaglandin F22α (cloprostenol; Estrumate®; MSD Animal Health Co.) at the time of CIDR removal. The cows entered the luteal phase approximately 14 days after exhibiting signs of estrus. They were then randomly assigned to three groups, each consisting of seven cows, and were immediately fed a mixture of concentrate and L. spinosa Thw. root powder supplements. These supplements were administered once a day for 21 days. Group 1 served as the control group, Group 2 received 15 g/cow/day of the supplement, and Group 3 received 30 g/cow/day of the supplement. Preparation of the supplement and feeding to the animalsPlant specimens were obtained from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Mahanakorn University of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand. Fresh L. spinosa Thw. roots were washed to remove any dirt or soil, cut into small pieces, and dried at 40°C in an oven with 10%–13% moisture. They were then ground into a powder. The powder was weighed and mixed with the concentrate, which was fed to the cows in the morning. We ensured that all cows consumed their entire mixture daily. Blood collection and plasma estradiol hormone levels determinationBlood samples (5 ml/cow) were randomly collected (in heparin anticoagulant tubes) from five cows in each group to measure plasma E2 levels. Blood samples were collected on day 35 after the signs of estrus began (1 day after the supplement was withdrawn) or on the same day as the follicle determinations and OPUs. Samples were stored on an ice pad and transported to the laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Mahanakorn University of Technology. The samples were centrifuged at 3000× g for 5 minutes to collect plasma samples, which were stored at −70 °C until the measurement of E2 levels, which were determined by radioimmunoassay according to a previously described protocol (Kamonpatana et al., 1976). Follicle determinationThe follicles of all cows were examined 1 day after supplement withdrawal. The follicle size was determined using real-time ultrasound (Sonoscape A6®, SonoScape, Shenzhen, China) with a 7.5-MHz linear transducer scanner. Follicles were categorized as small (<5 mm), medium (5–9 mm), or large (>9 mm), as described by Kajaysri and Intrarapuk (2024). The number of follicles in each class of size was recorded. Follicle aspirations and OPUsAfter determining the follicular sizes, all cow follicles were immediately aspirated for OPU. Follicle aspiration and OPU were performed according to the protocol outlined by Kajaysri and Intrarapuk (2024). Each cow was done epidural anesthesia with a single injection of 100 mg (5 ml) of 2% lidocaine hydrochloride (Lidocaine 2% Injection, Union Drug Laboratories, Bangkok, Thailand) to ease the rectum and lessen abdominal tension during the follicular aspiration. This allowed the cows to be palpated. Figure 1 shows the experimental design, including the hormone protocol, supplementation, blood collection, follicle determination, and OPU.

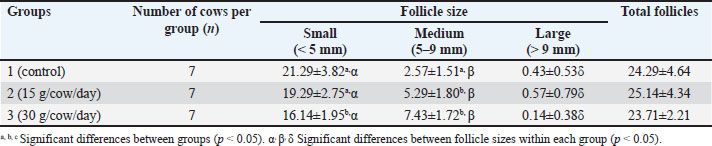

Fig. 1 The experimental design to evaluate the effect of supplementing feed with L. spinosa Thw. on ovarian function before OPU in crossbred Brahman cattle. CIDR: controlled internal drug release, IM: intramuscular, PGF2α, prostaglandin F2α, OPU: ovum pick-up. Oocyte evaluationsFollowing the morphological criteria outlined by Hidaka et al. (2018) and Kouamo et al. (2014), oocytes were harvested using OPU and examined using a 10x stereoscope (Nikon SMZ800N, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The oocytes obtained from each group were graded A–D based on the quality of the cumulus. In grade A cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs), compressed cumulus cells were arranged into >4 layers, and the ooplasm was homogenous. Grade B COCs were characterized by a uniform ooplasm in the three to four layers of the compacted cumulus cells. The ooplasm of the cumulus cell layers of Grade COCs were irregular, contained black granules, and had a low density. A paucity of COCs and denudation characterized-grade D COCs. Large cumuli with a jelly-like texture were observed in grade E oocytes. Grade E oocytes were excluded from the statistical analysis. Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The number of follicles and oocytes and the plasma estradiol concentrations are presented as the mean (per cow) ± SD. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data, after which Mann–Whitney U tests, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted. The least significant difference was evaluated if the ANOVA revealed a significant difference. For all tests, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Ethical approvalThe use of experimental animals in this study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Mahanakorn University of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand (approval no. ACUC-MUT-2021/002). ResultsOvarian follicle dynamics were expressed in terms of the average total number of follicles and the number of follicles in each size class per cow (Table 1). The total number of follicles did not significantly differ among the three groups. Small and large follicles were the most and least numerous of the size classes, respectively (p < 0.05), in all three groups. The number of large follicles did not significantly differ between the groups. However, the number of small follicles was significantly lower in Group 3 than in Groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.05), whereas the number of small follicles did not differ between Groups 1 and 2. Group 1 had significantly fewer medium follicles than Groups 2 and 3 (p < 0.05), which did not differ from one another. Table 1. Mean ± SD number of small, medium, large, and total follicles per cow following feed supplementation with 0, 15, or 30 g/cow/day of L. spinosa Thw.

Oocytes were collected from all follicle sizes in the ovaries of cows in each group using OPU. Table 2 shows the total number of oocytes and the number of each oocyte grade collected per cow in each group. In total, 312 oocytes (excluding grade E oocytes) were collected from 512 follicles, with an oocyte recovery rate of 60.94%. In Groups 1, 2, and 3, 110 (35.26%), 105 (33.65%), and 97 (31.09%) oocytes were collected, respectively. Each group evaluated the collected oocytes for grades A–D based on the quality of the cumulus. The total number of oocytes (grades A–D) collected per cow did not significantly differ between the groups. In Group 1, A-grade oocytes were the least numerous (p < 0.05), and D-grade oocytes were the most numerous. The number of oocytes graded A, B, C, and D did not differ significantly within Group 2. In Group 3, grade B oocytes were the most numerous (p < 0.05), and grade D oocytes were the least numerous. Table 2. Mean ± SD number of A, B, C, and D graded oocytes and total oocytes per cow following feed supplementation with 0, 15, or 30 g/cow/day of L. spinosa Thw. (n=7).

Table 3 presents the mean numbers (means ± SD) of oocytes graded A, B, C, and D and the combined oocyte grades A + B and C + D within the groups. Group 1 had significantly fewer grade A oocytes than the other two groups (p < 0.05), which did not significantly differ from each other. Group 1 versus Group 2 and Group 2 versus Group 3 did not differ significantly in the number of B- and C-grade oocytes, whereas Group 3 had oocytes with grades B and C greater and lesser than those of Group 1 (p < 0.05). In addition, Group 3 had significantly fewer grade D oocytes than the other two groups (p < 0.05; Groups 1 and 2 did not differ significantly in the number of grade D oocytes). Table 3. Mean±SD numbers of graded oocytes in grades A, B, C and D and combined oocyte grades A+B and C+D among different L. spinosa Thw. concentration treatment groups (n=7).

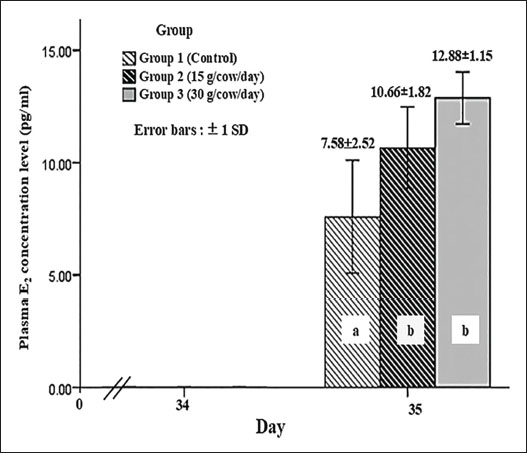

Only grade A and B oocytes were used worldwide for IVF and IVP procedures. Thus, this study also considered the combined A + B and C + D grades. Grade A+B oocyte numbers in Group 2 were similar to those in Groups 1 and 3, but Group 3 had significantly more oocytes than Group 1 (p < 0.05). The three groups significantly differed in the number of grade C+D oocytes (p < 0.05). Group 1 had the most, followed by Group 2, whereas Group 3 had the fewest. In addition, the plasma estradiol concentrations of five cows in each group were measured to evaluate whether L. spinosa Thw. supplementation in animal feed provided the phytoestrogen hormone to stimulate ovarian function in cows. Figure 2 shows the plasma E2 levels 1 day after the withdrawal of L. spinosa Thw. supplementation (day 35 after the onset of estrus signs in cows) in all three study groups. Group 1 had a significantly lower plasma E2 concentration than Groups 2 and 3 (p < 0.05), which did not significantly differ from each other.

Fig. 2 The plasma estradiol (E2) hormone levels one day after L. spinosa Thw. supplement withdrawal (day 35 after estrus-induced cows began to exhibit estrus signs) in three study groups of crossbred Brahman cattle (n=5 in each group). a, b=significant difference between groups (p < 0.05). DiscussionThe advantages of OPU-IVP in enhancing crossbreeding of Japanese Black cattle using EB treatment before OPU have been reported previously (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). EB can improve the quantity of high-quality oocytes (grades A and B) after OPU collection. This means that high-quality oocytes can contribute to the efficiency of bovine embryo production in situ, thereby increasing the number of calves in the industry (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). However, the use of synthetic estrogen hormones in beef cattle is sometimes limited. Phytoestrogen is an alternative hormone that can be used to enhance the production of high-quality oocytes. We hypothesized that L. spinosa Thw. is rich in natural estradiol and can synchronize the follicular wave and provide an increased quantity of medium-sized follicles and high-quality oocytes, as well as synthetic estradiol hormonal treatment before OPU collection in beef cattle. Unfortunately, research on the effects of phytoestrogens in L. spinosa Thw. on ovarian function before OPU in cattle is limited. The optimal quantity of L. spinosa Thw. required to stimulate ovarian function before OPU in beef cattle remains unclear. Suthikrai et al. (2007) supplemented the feed of swamp buffalo with 30 g of dry L. spinosa Thw. powder per animal per day to study its effect on their growth and reproductive hormones. This study was guided by previous research and used L. spinosa Thw. root powder at two different dosages: 15 and 30 g/cow/day. After 21 days of L. spinosa Thw. supplementation, the cows in the two treatment groups (Groups 2 and 3, which were supplemented with 15 and 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw., respectively) had the highest number of small follicles and the lowest number of large follicles when compared within the same group, resembling the pattern observed in cows treated with EB. The number of medium follicles fell between the small and large follicle numbers, aligning with the findings of a previous study (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). This indicates that both 21-day treatment doses (15 and 30 g/cow/day) of the L. spinosa Thw. supplements effectively stimulated natural estradiol production, synchronized the follicular wave, reduced the number of large follicles, and increased the number of medium follicles (Bo et al., 1995; Araujo et al., 2009; Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). Moreover, Group 3 (30 g/cow/day supplement) had the fewest small follicles, but the number of medium follicles was not different from that in Group 2 (15 g/cow/day supplement). In contrast, the number of medium follicles was the lowest in Group 1 (control group). The results indicated that the two groups with L. spinosa Thw. supplements had more medium-sized follicles than the control group. Furthermore, crossbred Brahman cattle treated with a 30 g/cow/day supplement showed a tendency to have more medium-sized follicles than those supplemented with 15 g/cow/day. Normally, cows give birth to one calf at a time. In each follicular wave cycle, there is a decreasing, moderate, and increasing number of large, medium, and small follicles, respectively. This process results in the development of one dominant follicle and the release of one oocyte during ovulation. The elevated blood E2 concentration from L. spinosa Thw. supplements could stimulate the growth of small follicles into medium-sized follicles within the follicular wave. Simultaneously, it could impede the growth rate of medium follicles, preventing them from reaching a larger size, thus increasing the number of medium follicles and reducing the number of small and large follicles. The findings also indicated a higher number of medium follicles in Groups 2 and 3 compared with Group 1 (control), with the control group showing a tendency toward the highest number of small follicles. Furthermore, Groups 2 and 3 produced fewer large-sized follicles than medium-sized follicles within the same group. This was likely due to the higher natural E2 content in the 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. supplement than in the 15 g/cow/day supplement. Overall, cows fed the 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. supplement tended to have more medium-sized follicles than those fed with the 15 g/cow/day supplement. Previous studies have recommended a dosage of 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. supplement for animal feed (Suthikrai et al., 2007; Jintana et al., 2013). The total number of oocytes per cow collected from bovine follicles did not vary with the dose of L. spinosa Thw. supplementation. The oocyte recovery rate was 60.94%, which was higher than previously reported (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). Group 1 had fewer grade B oocytes than grade D oocytes, whereas the number of grade A, B, C, and D oocytes did not differ in Group 2. In Group 3, the number of grade B oocytes was the highest. This pattern is similar to the number of grade B oocytes harvested from cows treated with EB in a previous study (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). It was possible that the 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. supplementation for 21 days was the optimal dose for treating beef cattle to provide the greatest number of good-quality oocytes (such as grade B oocytes) comparable to EB treatment. In addition, Group 1 produced the fewest grade A oocytes, but the number of grade B oocytes did not differ between Groups 1 and 2. The numbers of grade A and B oocytes in Group 2 were not different from those in Group 3, and these numbers in Group 2 were similar to those found in the EB treatment group in a previous study (Kajaysri and Intrarapuk, 2024). On the other hand, the number of grade A and B oocytes in Group 3 trended to be higher than that in Group 2. Therefore, treatment with the L. spinosa Thw. in this study, as an alternative to EB treatment, could be effective in improving the ovarian function of beef cattle before OPU. Moreover, because only grade A and B oocytes (high-quality oocytes) are considered for IVF and IVP procedures (El-Sanea et al., 2021), the combined number of grade A+B oocytes was significantly higher in Group 3 than in Group 1. Groups 1 and 2 and Groups 2 and 3 were not significantly different in this regard. However, Group 3 had trend of the highest number of grade A+B oocytes. Therefore, 30 g/cow/day of dry L. spinosa Thw. for 21 days was the optimal dose to supplement animal feed to increase the quantity of high-quality oocytes before OPU in crossbred Brahman cattle. In addition, plasma E2 concentrations were measured 1 day after L. spinosa Thw. supplementation was discontinued. Both groups were treated with L. spinosa Thw. presented with higher levels of plasma E2 than the control group (Group 1). These results confirmed that L. spinosa Thw. supplementation in cattle feed for 21 days effectively increased the plasma E2 level of cattle supplemented with L. spinosa Thw. to above that of cattle without supplementation. Previous reports (Kumro et al., 2021) have maintained that the plasma E2 level in the luteal phase is 8 pg/mL in cattle not treated with any hormones. This level was similar to that observed in the control group (Group 1). However, the plasma E2 levels did not differ between Groups 2 and 3. This might be due to the limited sample size, as only 5 cows per group were used for E2 analyses. The limited number of specimens was a constraint of this study. Additionally, the natural E2 in L. spinosa Thw. could be metabolized in the ruminant digestive system, resulting in reduced blood absorption, which might have affected the plasma E2 levels in both treatment groups. Nevertheless, the cattle in Group 3 tended to have the highest plasma E2 level and the highest number of medium follicles and grade A and grade B oocytes, likely because they received a higher dose of L. spinosa Thw. compared to Group 2. This indicated that supplementation with 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. for 21 days was the optimal dose for stimulating high E2 plasma levels in the luteal phase and synchronizing and regulating follicular waves. In this study, it also resulted in the largest number of high-quality oocytes after OPU, indicating that this treatment could enhance outcomes compared with EB (Kaminski et al., 2019). This study concluded that supplementing donor cows with 30 g/cow/day of L. spinosa Thw. powder for 21 days before OPU was the most effective method in enhancing ovarian function, promoting follicle growth, and producing more high-quality oocytes compared to unsupplemented cows, with a tendency to outperform other supplementation doses. The outcomes of 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. supplementation was comparable with that of EB hormone treatment in beef cattle, as reported previously. Therefore, supplementation with this dose of L. spinosa Thw. was considered the most beneficial and effective for enhancing follicle and oocyte development before OPU. The authors suggested using a 30 g/cow/day L. spinosa Thw. supplement for 21 days as a substitute for EB treatment, a natural androgen hormone. This alternative offers comparable efficacy with fewer side effects on cattle and lower hormone residues in meat. This protocol effectively enhances ovarian function before the onset of OPU in crossbred Brahman cattle. Future research should investigate the side effects, toxic dosage, additional efficacy, and other benefits of L. spinosa Thw. supplements for beef cattle feed. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank the private beef farm in Kanchanaburi province, Thailand, for providing animal samples and Mahanakorn University of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, for providing research facility support. FundingIn-kind funding has been subsidized for the research facility by Mahanakorn University of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, and animal specimens, including the OPU facility, by the private beef farm in Kanchanaburi province, Thailand. Authors’ contributionJatuporn Kajaysri (JK) and Apiradee Intarapuk (AI): Both authors participated in the experimental design and conducted the experiment. JK: Conducted a comprehensive literature search, performed the experimental work, collected data, drafted, revised, and proofread the manuscript. AI: AI: Assisted in collecting and analyzing the collected data. Both authors have read, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the authors. ReferencesAraujo, R.R., Ginther, O.J., Ferreira, J.C., Palhao, M.M., Beg, M.A. and Wiltbank, M.C. 2009. Role of follicular estradiol-17beta in timing of luteolysis in heifers. Biol. Reprod. 81, 426–437. Balboula, A.Z., Aboelenain, M., Sakatani, M., Yamanaka, K.I., Bai, H., Shirozu, T., Kawahara, M., Hegab, A.E.O., Zaabel, S.M. and Takahashi, M. 2022. Effect of E-64 supplementation on the developmental competence of bovine OPU-derived oocytes during in vitro maturation. Genes. 13, 324. Baruselli, P.S., Rodrigues, C.A., Ferreira, R.M., Sales, J.N.S., Elliff, F.M., Silva, L.G., Viziack, M.P., Factor, L. and D’Occhio, M.J. 2021. Impact of oocyte donor age and breed on in vitro embryo production in cattle, and relationship of dairy and beef embryo recipients on pregnancy and the subsequent performance of offspring: a review. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 34, 36–51; doi:10.1016/j.rfd.2013.09.012 Bo, G.A., Adams, G.P., Caccia, M., Martinez, M., Pierson, R.A. and Mapletoft, R.J. 1995. Ovarian follicular wave emergence after progestogen and estradiol treatment in cattle. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 39, 193–204. Crowe, A.D., Lonergan, P. and Butler, S.T. 2021. Invited review: use of assisted reproduction techniques to accelerate genetic gain and increase value of beef production in dairy herds. Dairy Sci. 104, 12189–12206. Demetrio, D., Looney, C., Rees, H. and Werhman, M. 2020. Statistical information committee report (2019 data). Annual Report of the AETA Statistical Information Committee. American embryo transfer association. Available via https://www.aeta.org/Portals/0/siteContent/Public/Resources/Report%20&%20Export%20Charts/2019%20Report%20&%20Export%20Chart.pdf (Aceesed 1 April 2025) Doublet, A.C., Restoux, G., Fritz, S., Balberini, L., Fayolle, G., Hozé, C., Laloë, D. and Croiseau, P. 2020. Intensified use of reproductive technologies and reduced dimensions of breeding schemes put genetic diversity at risk in dairy cattle breeds. Anim. Anim. (Basel). 10, 1903. Egashira, J., Ihara, Y., Khatun, H., Wada, Y., Konno, T., Tatemoto, H. and Yamanaka, K.I. 2019. Efficient in vitro embryo production using in vivo-matured oocytes from superstimulated Japanese black cows. J. Reprod. Dev. 65, 183–190. El-Sanea, A.M., Abdoon, A.S.S., Kandil, O.M., El-Toukhy, N.E., El-Maaty, A.M.A. and Ahmed, H.H. 2021. Effect of oxygen tension and antioxidants on the developmental competence of buffalo oocytes cultured in vitro. World 14, 78–84. Faber, D.C., Molina, J.A., Ohlrichs, C.L., Vander Zwaag, D.F. and Ferre, L.B. 2003. The commercialization of animal biotechnology. Theriogenology 59, 125–138. Ferré, L.B., Gallardo, H.A., Romo, S., Fresno, C., Stroud, T., Stroud, B., Lindsey, B. and Kjelland, M.E. 2023. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval in cattle: state-of-the-art and its impact on the in vitro fertilization embryo production outcome. Domest. Anim. 57, 363–378. Fry, R.C. 2020. Gonadotropin priming before OPU: what are the benefits in cows and calves?. Theriogenology 150, 236–240. Galli, C., Crotti, G., Notari, C., Turini, P., Duchi, R. and Lazzari, G. 2001. Embryo production by ovum collection from live donors. Theriogenology 55, 1341–1357. Galli, C., Duchi, R., Colleoni, S., Lagutina, I. and Lazzari, G. 2014. Ovum pick-up, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and somatic cell nuclear transfer in cattle, buffaloes, and horses: from the research laboratory to clinical practice. Theriogenology 81, 138–151. Hidaka, T., Fukumoto, Y., Yamamoto, Y., Ogata, Y. and Horiuchi, T. 2018. Estradiol benzoate treatment before ovum pick-up increases the number of retrieved good-quality oocytes and improves transferable embryo production in Japanese Black cattle. Vet. Anim. Sci. 5, 1–6. Hong Van, N.T., Minh, C.V., De Leo, M., Siciliano, T. and Braca, A. 2006. Secondary metabolites from L. spinosa Thw. (Araceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 34, 882–884. Jintana, R., Suthikrai, W., Sophon, S., Hengtrakulsin, R., Usawang, S. and Kamonpatana, M. 2013. Effects of Lasia spinosa Thw. and season on plasma leptin and glucose levels in weaned female murrah × swamp buffalo calves. Buffalo Bull. 32(2), 947–950. Kaewamatawong, T., Suthikrai, W., Bintvihok, A. and Banlunara, W. 2013. Acute to subchronic toxicity and reproductive effects of aqueous ethanolic extract of Lasia spinosa Thw. rhizomes in male rats. Thai. J. Vet. Med. 43, 69–74. Kajaysri, J. and Intrarapuk, A. 2024. Effectiveness of different hormone protocols for improving ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Japanese black cattle. Vet. World 17, 1362–1369. Kaminski, A.P., Carvalho, M.L.A., Segui, M.S., Kozicki, L.E., Pedrosa, V.B., Weiss, R.R. and Galan, T.G.B. 2019. Impact of recombinant bovine somatotropin, progesterone, and estradiol benzoate on ovarian follicular dynamics in Bos taurus taurus cows using estrus and ovulation synchronization protocol. Theriogenology 140, 58–61. Kamonpatana, M., Luvira, Y., Bodhipaksha, P. and Kunawongkrit, A. 1976. Serum progesterone, 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone and 17-β Estradiol during estrous cycle in swamp buffalo in Thailand: a preliminary report. In Proc. of Int. Symp.on Nuclear Techniques in Animal Production and Health as Related to the soil plant system, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria, 17, pp 569–578. Kankanamge, S.U., Amarathunga, A., Sanjeewani, N. and Samanmali, B. 2017. Phytochemical and ethno-pharmacological properties of Lasia spinosa (Kohila): a review. World J. Pharm. Res. 6, 1–9. Kouamo, J., No Author, N.A., Dawaye, S. and Bah, A. 2014. Evaluation of bovine (Bos indicus) ovarian potential for in vitro embryo production in the Adamawa Plateau, Cameroon. Open Vet. J. 4, 128–136. Kruip, T.A., Boni, R., Wurth, Y.A., Roelofsen, M.W. and Pieterse, M.C. 1994. Potential use of ovum pick-up for cattle embryo production and breeding. Theriogenology 42, 675–684. Kumro, F.G., Smith, F.M., Yallop, M.J., Ciernia, L.A., Caldeira, M.O., Moraes, J.G.N., Poock, S.E. and Lucy, M.C. 2021. Short communication: simultaneous measurements of estrus behavior and plasma concentrations of estradiol during estrus in lactating and nonlactating dairy cows. Dairy Sci. 104, 2445–2454. Looney, C.R., Lindsey, B.R., Gonseth, C.L. and Johnson, D.L. 1994. Commercial aspects of oocyte retrieval and in vitro fertilization (IVF) for embryo production in problem cows: a case report. Theriogenology 41, 67–72. Majerus, V., De Roover, R., Etienne, D., Kaidi, S., Massip, A., Dessy, F. and Donnay, I. 1999. Embryo production by ovum pick-up in unstimulated calves before and after puberty. Theriogenology 52, 1169–1179. Merton, J.S., De Roos, A.P.W., Mullaart, E., De Ruigh, L., Kaal, L., Vos, P.L.A.M. and Dieleman, S.J. 2003. Factors affecting oocyte quality and quantity in the commercial application of embryo technologies in cattle breeding. Theriogenology 59, 651–674. Numabe, T., Oikawa, T., Kikuchi, T. and Horiuchi, T. 2001. Birth weight and gestation length of Japanese black calves following transfer of embryos produced in vitro with or without co-culture. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 63, 515–519. Suthikrai, W., Jintana, R., Sophon, S., Hengtrakulsin, R., Usawang, S. and Kamonpatana, M. 2007. Effects of L. spinosa Thw. on growth rate and reproductive hormone levels in weaned Swamp buffalo and Murrah × Swamp buffalo calves. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 6(Suppl. 2), 532–535. Taneja, M., Bols, P.E., Van De Velde, A., Ju, J.C., Schreiber, D., Tripp, M.W., Levine, H., Echelard, Y., Riesen, J. and Yang, X. 2000. Developmental competence of juvenile calf oocytes in vitro and in vivo: influence of donor animal variation and repeated gonadotropin stimulation. Biol. Reprod. 62, 206–213. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Kajaysri J, Intarapuk A. Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(10): 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 Web Style Kajaysri J, Intarapuk A. Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=253772 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Kajaysri J, Intarapuk A. Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(10): 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Kajaysri J, Intarapuk A. Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(10): 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 Harvard Style Kajaysri, J. & Intarapuk, . A. (2025) Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. Open Vet. J., 15 (10), 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 Turabian Style Kajaysri, Jatuporn, and Apiradee Intarapuk. 2025. Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (10), 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 Chicago Style Kajaysri, Jatuporn, and Apiradee Intarapuk. "Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Kajaysri, Jatuporn, and Apiradee Intarapuk. "Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle." Open Veterinary Journal 15.10 (2025), 5326-5334. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Kajaysri, J. & Intarapuk, . A. (2025) Effect of Lasia spinosa Thwaites (L. spinosa Thw.) supplementation in animal feed on ovarian function before ovum pick-up in crossbred Brahman cattle. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (10), 5326-5334. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i10.49 |