| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2774-2781 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2774-2781 Research Article Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian marketsMona Mohammed I. Abdel Rahman1, Noha B. Elbarbary2, Wageh Sobhy Darwish3*, Rehab E. Mohamed4, Elham Elsayed Abo-Almagd5, Nafissa A. Mustafa6 and Elshimaa A. A. Nasr61Parasitology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt 2Parasitology Department, Animal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Mansoura provincial Lab (AHRI-Mansoura), Agriculture Research Center (ARC), Giza, Egypt. 3Food Hygiene, Safety, and Technology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt 4Department of Zoonosis, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt 5Oncology Center, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt 6Educational Veterinary Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt *Correspondence to: Wageh Sobhy Darwish. Food Hygiene, Safety, and Technology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt. Email: wagehdarwish [at] gmail.com Submitted: 25/04/2025 Revised: 07/05/2025 Accepted: 08/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

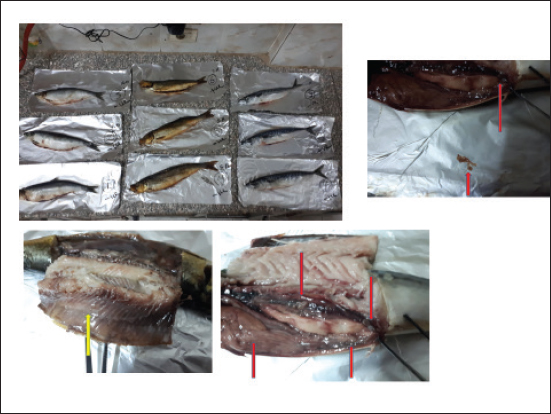

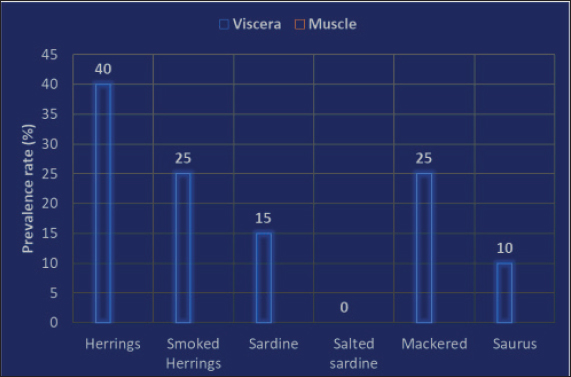

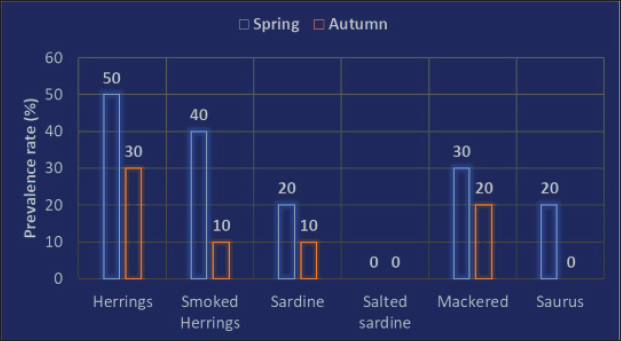

AbstractBackground: An abundance of vitamins, minerals, and vital amino acids can be found in fish. The parasitic zoonotic disease anisakiasis is caused by ingesting the third larval stage of Anisakis spp., which is carried by nematodes called anisakids. Serious health problems, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and allergic reactions that could approach anaphylactic level, are brought to the human body by ingesting undercooked fish, where this parasite is present. Aim: Raw herrings, smoked herrings, raw sardines, salted sardines, raw mackerel, and raw saurus were all tested for the presence of Anisakis larvae. Methods: Fish samples were purchased from Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, with half of the samples from all species being collected in the spring and the other half being collected in the autumn. Parasitic examination of fish was done morphologically and confirmed using PCR. Results: The detection rates of Anisakis larvae in raw herrings, smoked herrings, raw sardine, salted sardine, raw mackerel, and raw saurus fish were 40%, 25%, 15%, 0%, 25%, and 10%, respectively. No muscle samples were found to be infested with Anisakis spp. Based on the findings, it was discovered that the fish that were sampled in spring had a higher infestation rate with Anisakis larvae than that collected in autumn. The hazards associated with Anisakis larvae were further discussed. Conclusion: The examined fish species in the present study were found to be infested with Anisakis larvae at variable rates except for salted sardine. Therefore, efficient cooking of fish before serving to human is highly recommended. Keywords: Fish, Anisakis larvae, Egypt, Public health. IntroductionAccording to several studies (Morshdy et al., 2013, 2019; El-Ghareeb et al., 2021), fish is a great way to get a lot of vitamins, minerals, vital amino acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and high-quality protein. Fish may contain all of these nutrients. Conversely, fish is often thought of as a potential vector for food-borne diseases, including parasites, molds, and germs. According to the World Health Organization (2012), there have been almost 56 million cases of human infections with parasite disorders linked to eating fish. Anisakiasis is a parasitic zoonotic disease associated with nematodes called anisakids. The third stage of the Anisakis larvae (L3) is the vector for the transmission of this disease from host to host. Marine fish are the most common hosts for this parasite, which also infests crustaceans, cephalopods, and other types of fish. This parasite also feeds on fish (Nieuwenhuizen and Lopata, 2013). The principal agents responsible for the disease have been identified as Anisakis simplex, Anisakis pegreffii, and Anisakis physeteris (Mattiucci and Nascetti, 2008). Consumption of raw or undercooked fish, including popular Japanese dishes such as sushi and sashimi, can lead to people exposure to anisakis (Pampiglione et al., 2002). Additionally, several anisakid antigens are thermostable, which is a major concern for human health (European Food Safety Association, 2010; Caballero et al., 2011). In humans, anisakiasis manifests as violent nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain. Ulcers of the stomach and duodenum, appendicitis, and peritonitis can develop as the disease progresses. You have the condition if you experience any of these symptoms. Some people who are very vulnerable to the disorder also exhibit critical symptoms, such as hypersensitivity, urticaria, and anaphylaxis (Villazanakretzer et al., 2016). Stage 3 Anisakis larvae have been found in many different kinds of fish around the globe. For Egypt and other Mediterranean nations, herrings are among the most valuable fish species. Additionally, they are vital to the economies of those nations and the seafood trade that those nations rely on. You can get herrings in Egypt either raw or smoked. Most people prefer raw herrings. The latter is highly popular in Egypt because of its unique scent and taste. Another important host for Anisakis species is herrings, according to research (Bao et al., 2017; Guardone et al., 2017). Fish such as sardines, mackerel, and saurus are also common in Egyptian cuisine and are notable for their high nutritional value. Anisakis species also have these fish as natural hosts. Research on the prevalence of Anisakis larvae in Egyptian fish, especially commercially traded species such as herrings, mackerel, sardines, and saurus, has received less attention than anticipated. Considering the background information, this study set out to examine the prevalence of Anisakis species in several retail fish products supplied in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, including raw and smoked herrings, sardine, salted sardines, mackerel, and saurus. Afterward, a discussion on the public health importance of this nematode was proceeded. Material and MethodsCollection of samplesA total of 120 random whole fish and fish product samples, with 20 samples from each of raw herrings (Clupea harengus Linnaeus, 1758), smoked herrings, sardines (Sardinella aurita), salted sardines, mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma), and saurus (Elops saurus) fish included in the collection. Fish samples were collected from fish markets in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, in 2024 with half of the samples from all species being collected in the spring and the other half being collected in the autumn. There was no damage to the fish samples, and they had a normal aroma and flavor. In order to conduct a parasitological analysis, the samples were immediately and without delay sent to the laboratory after being cooled. Fish examinationSamples of fish were dissected and examined using a stereoscopic microscope to determine whether or not they contained Anisakid larvae. This was done by carefully inspecting the fish viscera throughout the examination. The muscles of fish were subjected to an artificial enzymatic digestion, as described by Llarena-Reino et al. (2013), and the product that was produced was analyzed using a stereoscopic microscope. Morphological identificationAll of the anisakids that were found were recognized based on the morphological characteristics that were discussed earlier (Gibbons, 2010). Molecular confirmationDNA extractionIn accordance with Guardone et al. (2016), DNA extraction from larvae per sample was carried out. In addition, the integrity of the DNA was examined further in accordance with Giusti et al. (2019). Amplification of cytochrome c oxidase IIAmplification of the cytochrome c oxidase II (cox2) gene was carried out in accordance with the instructions provided by Guardone et al. (2018). The cycling conditions that were employed for the amplification operations began with denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes. This was followed by 45 cycles, each containing denaturation at 95°C for 20 seconds, annealing at 52°C for 20 seconds, extension at 72°C for 25 seconds, and then followed by a 10-minute final extension at 72°C. Ethical DeclarationThis study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of Zagazig University, Egypt, and received the ethical approval number ZU-IACUC/2/F/298/2024. Statistical analysisThe total prevalence and distribution of the anisakid larvae were analyzed in accordance with Bush et al. (1997). This analysis was performed in connection to either visceral organs or the muscle as the site of infestation, as well as the collection season of the samples. ResultsThe obtained results in the current investigation showed an overall prevalence of Anisakis larvae in raw herrings, smoked herrings, raw sardine, salted sardine, mackerel, and saurus fish at 40% (8 out of 20 samples examined), 25% (5 out of 20 samples examined), 15% (3 out of 20 samples examined), 0%, 25% (5 out of 20 samples examined), and 10% (2 out of 20 samples examined), respectively. No muscle samples were found to be infested with Anisakis spp. (Figs. 1 and 2). Based on the findings that were documented in Figure 3, it was discovered that the fish that were sampled in spring had a higher infestation rate with Anisakis larvae than that collected in autumn. The prevalence rates in spring and autumn in herrings were 50% and 30%, respectively, in smoked herrings such values were 40%, and 10%. In raw sardine, such rates were 20%, and 10%, respectively, while not detected in salted sardine. In mackerel, such rates were 30%, and 20%, while in saurus, it was only detected in spring at 20%. The detection of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products from other reports was presented in Table 1, while the potential adverse effects for such parasites were presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1. Detection of Anisakis species in the retailed fish species in Egypt.

Fig. 2. Prevalence rate (%) of Anisakis species in the examined fish species in the current investigation.

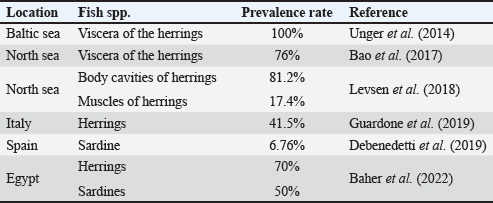

Fig. 3. Prevalence of Anisakis species in the examined fish species in the current investigation in relation to the season. Table 1. Reported prevalence rates of Anisakis larvae in different fish species.

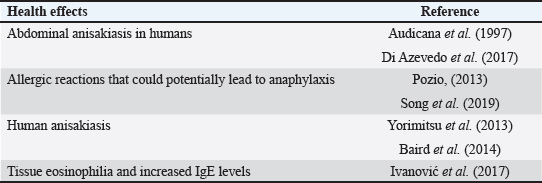

Table 2. Reported public health hazards of Anisakis larvae due to consumption of fish.

DiscussionFish species such as herrings, sardines, mackerel, and saurus are considered to be among the most valuable in the Egyptian market. These kinds of fish are served either fried or grilled, or they are put through additional manufacturing and processing procedures in order to create new kinds of fish products, such as salted sardines or smoked herrings. However, suck fish and fish products might be considered potential sources for some infectious agents and parasites such as Anisakis larvae. The obtained results demonstrated that the rate of fish infestation with Anisakis larvae was significantly higher in raw herrings than in other examined fish species. In particular, there was a clear occurrence of the larvae in the viscera of the examined fish species than the muscle tissue. In accordance with the findings that were obtained in the present investigation, Unger et al. (2014) found that the viscera of the herrings that were collected from the Baltic Sea had 100% of Anisakis larvae. Anisakis larvae were found in the visceral organs of 76% of the herrings that were collected from the North Sea, according to observations made by Bao et al. (2017). Another study conducted by Levsen et al. (2018) found that the parasite was present in the body cavity of 81.2% of the herrings that were collected from the North Sea, and it was found in 17.4% of the muscles. A further finding was that Anisakis larvae were found in 41.5% of the herrings and herring products that were sold in Italy, according to Guardone et al. (2019). In addition, Anisakis larvae were found in sardine that was taken from Spain at a percentage of 6.76% (Debenedetti et al., 2019). Sardine is generally believed to be a fish that has a low risk of anisakiosis due to the low prevalence rate (Gutiérrez-Galindo et al., 2010; Cavallero et al., 2015). In agreement with the inter-species variations in the prevalence of Anisakis spp., Debenedetti et al. (2019) recorded a clear difference in the prevalence rates of Anisakis larvae in several fish species (hake, mullet, sardine, mackerel, and anchovy) taken from the Atlantic Ocean compared to the same fish species collected from the Mediterranean Sea. In Albania, 361 (33.58%) of the 1,075 samples examined had L3 larvae parasites. To be more specific, the only one that came out negative was Solea vulgaris. On the other hand, the three species with the lowest prevalence and mean abundance were Sparus aurata (4.55%), Dicentrarchus labrax (9.17%), and S. aurita (0.84, 1.19, and 0.92, respectively). On the other hand, mackerel (Scombber scombrus) had the highest mean abundance of 249.82 and the highest prevalence of 74.07%, while Scombber japonicus had 68.00%. The results indicate that there is a potential for zoonotic diseases to be prevalent in the coastal area of the Karaburun Peninsula in southern Albania. Human anisakiasis could be contracted from eating raw or undercooked fish captured in the Vlora district (Ozuni et al., 2021). In Egypt, Baher et al. (2022) detected Anisakis larvae at 70% and 50% of the examined herrings and sardines. It is for this reason that the origin of the fish must be taken into consideration as an essential component in order to lessen the likelihood of infection caused by this zoonotic parasite (Abollo et al., 2001; Silva and Eiras, 2003; Herrador et al., 2019). Sardine, mackerel, and saurus did not have a high-risk group, which would be defined as having more than 10 larvae per fish (Debenedetti et al., 2019). This is quite improbable. In accordance with the findings of Debenedetti et al. (2019), which indicated a distinct variance in the frequency of dispersion of Anisakis larvae in various fish species, such as anchovy, hake, sardine, mullet, and mackerel; the result that was achieved in the current study is in agreement with the findings of the aforementioned study. In all data analyzed, the high prevalence of the larvae in the viscera compared with the muscle was observed. People usually consume the fish muscle more than the viscera; however, cross-contamination of the muscle can take place during any step of fish preparation starting from evisceration, cleaning, or even migration of the larvae from the viscera to the flesh (Abollo et al., 2001). The highest prevalence of Anisakis species in the examined fish species was recorded in spring compared to autumn. Likely, over the course of a year, researchers in central Norway examined the seasonal variation in the infection of saithe, cod, and redfish with A. simplex third-stage larvae (L3). The parasite’s population peaked in March and April across all three host species, but it increased throughout the spring. The seasonal variation in cod was the most noticeable, with a noticeable abundance peak in April. Redfish did not see as sharp of an abundance peak in April. In saithe, the seasonal variation in abundance was less pronounced; the peak occurred in March, and there was an additional upsurge in July. There must be a myriad of factors at play here that led to the infection pattern seen in this study. There is evidence to support the idea that the two most influential elements controlling the “spring rise” in A. simplex L3 in the research region are the general bloom of plankton and the increased availability of parasite eggs from whales migrating northward (Strømnes and Andersen, 2000). The parasitic infection of fish with Anisakis larvae has a number of negative impacts on the fish’s health, beginning with inflammation that occurs during the larval penetration process and progressing to the various visceral organs, resulting in a major reduction in the physiological functions of these organs. Furthermore, according to Buchmann and Mehrdana (2016), Haarder et al. (2013), and Rohlwing et al. (1998), the larvae have the ability to excrete certain chemical compounds, such as pentanols and pentanones, which have local anesthetic effects on the muscles of the fish. As a result, these compounds have the ability to affect the swimming ability of the fish, making them extremely vulnerable to being eaten by their predatory fishes. Regarding the public health effects of Anisakis larvae, according to Audicana et al. (1997) and Di Azevedo et al. (2017), the consumption of fish that has been contaminated with Anisakis larvae may result in a number of negative health effects, one of which is abdominal anisakiasis in humans. This condition is caused by the larvae penetrating the mucosa of the stomach or the abdominal cavity. Moreover, allergic reactions that could potentially lead to anaphylaxis could take place, particularly in high-risk categories such as youngsters, the elderly, and patients who are unable to function normally (Pozio, 2013; Song et al., 2019). According to Baird et al. (2014), Japan is the nation that has the highest prevalence of infectious diseases caused by Anisakis in humans. The consumption of infected sushi and sashimi, which are considered to be the national dishes of raw fish, is a significant source of human infection. According to Yorimitsu et al. (2013), between 2,000 and 3,000 cases of anisakiasis are recorded each year in Japan. Infections in humans caused by nematodes and other helminths are generally linked to tissue eosinophilia and increased IgE levels, which may also manifest in patients exhibiting type I hypersensitivity to specific antigens (Ivanović et al., 2017). Among the effective strategies for preventing Anisakis infection are the following: preventing the migration of Anisakis larvae postmortem from viscera to flesh through visual inspection by fishermen or consumers and collecting the larvae manually; avoiding the consumption of raw or undercooked fish; cooking the fish effectively by allowing it to reach an internal temperature of 60°C for 1 to 3 minutes; freezing the fish for 24 hours at a temperature of 20°C; and pickling the fish in vinegar and salt, which is also considered to be a suitable method for reducing the dangers posed by Anisakis larvae (European Commission, 2011). ConclusionAnisakis larvae were detected in the examined fresh herrings, smoked herrings, fresh sardine, mackerel, and saurus fish at variable rates. Anisakis larvae were mainly detected in the viscera of the examined fish rather than the muscles. The prevalence in the spring was much higher than in autumn. Therefore, as a typical preventative measure to minimize the adverse effects of Anisakis larvae on the consumers, it is highly recommended to efficiently heat treat such kinds of fish. Conflict of interestNone. FundingThis study was self-supported. Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed equally. Data availabilityAll data related to this study were included in the manuscript. ReferencesAbollo, E., Gestal, C. and Pascual, S. 2001. Anisakis infestation in marine fish and cephalopods from Galician waters: an updated perspective. Parasitol. Res. 87, 492–499. Audicana, L., Audicana, M.T., Fernández de Corres, L. and Kennedy, M.W. 1997. Cooking and freezing may not protect against allergenic reactions to ingested Anisakis simplex antigens in humans. Vet. Rec. 140, 235. Baher, W.M., Darwish, W.S.E.A. and Elhelaly, A.E. 2022. Prevalence and public health significance of anisakis larvae in some marketed marine fish in egypt. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 10(6), 1303–1307. Baird, F.J., Gasser, R.B., Jabbar, A. and Lopata, A.L. 2014. Foodborne anisakiasis and allergy. Mol. Cellular Probes. 28(4), 167–174. Bao, M., Pierce, G., Pascual, S., Gonzalez-Munoz, M., Mattiucci, S., Mladineo, I., Cipriani, P., Buselic, I. and Strachan, N.J.C. 2017. Assessing the risk of an emerging zoonosis of worldwide concern: anisakiasis. Sci. Rep. 7, 43699. Buchmann, K. and Mehrdana, F. 2016. Effects of anisakid nematodes Anisakis simplex (s.l.), Pseudoterranova decipiens (s.l.) and Contracaecum osculatum (s.l.) on fish and consumer health. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 4, 13–22. Bush, A.O., Lafferty, K.D., Lotz, J.M. and Shostak, A.W. 1997. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 83, 575–583. Caballero, M.L., Umpierrez, A., Moneo, I. and Rodriguez-Perez, R. 2011. Anis 10, a new Anisakis simplex allergen: cloning and heterologous expression. Parasitol. Int. 60, 209–212. Cavallero, S., Magnabosco, C., Civettini, M., Boffo, L., Mingarelli, G., Buratti, P., Giovanardi, O., Fortuna, C.M. and Arcangeli, G. 2015. Survey of Anisakis sp. and Hysterothylacium sp. in sardines and anchovies from the North Adriatic Sea. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 200, 18–21. Debenedetti, Á.L., Madrid, E., Trelis, M., Codes, F.J., Gil-Gómez, F., Sáez-Durán, S. and Fuentes, M.V. 2019. Prevalence and risk of anisakid larvae in fresh fish frequently consumed in Spain: an overview. Fishes 4(1), 13. Di Azevedo, M.I.N., Carvalho, V.L. and Iñiguez, A.M. 2017. Integrative taxonomy of anisakid nematodes in stranded cetaceans from Brazilian waters: an update on parasite’s hosts and geographical records. Parasitol. Res. 116, 3105–3116. European Commission. 2011. Commission Regulation (EU) No 1276/2011 of 8 December 2011 amending Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the treatment to kill viable parasites in fishery products for human consumption. Off. J. Eur. Union L. 327, 39–41. European Food Safety Association (EFSA). 2010. Scientific opinion on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products. EFSA J. 8, 1543. Available via http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1543/e El-Ghareeb, W.R., Elhelaly, A.E., Abdallah, K.M.E., El-Sherbiny, H.M. and Darwish, W.S. 2021. Formation of biogenic amines in fish: dietary intakes and health risk assessment. Food Sci. Nutr. 9(6), 3123–3129. Gibbons, L.M. 2010. Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates, supplementari volume. Wallingford, England: CAB International, p: 416. Giusti, A., Tinacci, L., Sotelo, C.G., Acutis, P.L., Ielasi, N. and Armani, A. 2019. Authentication of ready-to-eat anchovy products sold on the Italian market by BLAST analysis of a highly informative cytochrome b gene fragment. Food Control 97, 50–57. Guardone, L., Malandra, R., Costanzo, F., Castigliego, L., Tinacci, L., Gianfaldoni, D., Guidi, A. and Armani, A. 2016. Assessment of a sampling plan based on visual inspection for the detection of anisakid larvae in fresh anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus). A first step towards official validation? Food Anal. Methods 9, 1418–1427. Guardone, L., Nucera, D., Lodola, L.B., Tinacci, L., Acutis, P.L., Guidi, A. and Armani, A. 2018. Anisakis spp. larvae in different kinds of ready to eat products made of anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) sold in Italian supermarkets. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 268, 10–18. Guardone, L., Nucera, D., Pergola, V., Costanzo, F., Costa, E., Guidi, A. and Armani, A. 2017. A rapid digestion method for the detection of anisakid larvae in European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus): Visceral larvae as a predictive index of the overall level of fish batch infestation and marketability. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 250, 12–18. Guardone, L., Nucera, D., Rosellini, N., Tinacci, L., Acutis, P.L., Guid, A. and Armani, A. 2019. Occurrence, distribution and viability of Anisakis spp. larvae in various kind of marketed herring products in Italy. Food Control 101, 126–133. Gutiérrez-Galindo, J.F., Osanz-Mur, A.C. and Moraventura, M.T. 2010. Occurrence and infection dynamics of anisakid larvae in Scomber scombrus, Trachurus trachurus, Sardina pilchardus, and Engraulis encrasicolus from Tarragona (NE Spain). Food Control 21, 1550–1555. Haarder, S., Kania, P.W., Bahlool, Q.Z.M. and Buchmann, K. 2013. Expression of immune relevant genes in rainbow trout following exposure to live Anisakis simplex larvae. Exp. Parasitol. 135, 564–569. Herrador, Z., Daschner, A., Perteguer, M.J. and Benito, A. 2019. Epidemiological scenario of anisakidosis in Spain based on associated hospitalizations: the tipping point of the iceberg. Clin. Inf. Dis. 69(1), 69–76. Ivanović, J., Baltić, M.Ž., Bošković, M., Kilibarda, N., Dokmanović, M., Marković, R., Janjić, J. and Baltić, B., 2017. Anisakis allergy in human. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 59, 25–29. Levsen, A., Svanevik, C.S., Cipriani, P., Mattiucci, S., Gay, M. and Hastie, L.C. 2018. A survey of zoonotic nematodes of commercial key fish species from major European fishing grounds—introducing the FP7 PARASITE exposure assessment study. Fisheries Res. 202, 4–21. Llarena-Reino, M., Piñeiro, C., Antonio, J., Outeriño, L., Vello, C., González, A.F. and Pascual, S. 2013. Optimization of the pepsin digestion method for anisakids inspection in the fishing industry. Vet. Parasitol. 191, 276–283. Mattiucci, S. and Nascetti, G. 2008. Advances and trends in the molecular systematics of anisakid nematodes, with implications for their evolutionary ecology and host parasite co-evolutionary processes. Adv. Parasitol. 66, 47–148. Morshdy, A.E., Hafez, A.E., Darwish, W.S., Hussein, M.A. and Tharwat, A.E. 2013. Heavy metal residues in canned fishes in Egypt. Jpn. J. Vet. Res. 61, S54–S57. Morshdy, A.E.M.A., Darwish, W.S., Daoud, J.R.M., Hussein, M.A.M. and Sebak, M.A.M. 2019. Monitoring of organochlorine pesticide residues in Oreochromis niloticus collected from some localities in Egypt. Slov. Vet. Res. 55, 303–311. Nieuwenhuizen, N. and Lopata, A. 2013. Anisakis - a food-borne parasite that triggers allergic host defences. Int. J. Parasitol. 43(12–13), 1047–1057. Ozuni, E., Vodica, A., Castrica, M., Brecchia, G., Curone, G., Agradi, S., Miraglia, D., Menchetti, L., Balzaretti, C.M. and Andoni, E. 2021. Prevalence of Anisakis larvae in different fish species in southern Albania: five-year monitoring (2016–2020). Appl. Sci. 11(23), 11528. Pampiglione, S., Rivasi, F., Criscuolo, M., De Benedittis, A., Gentile, A., Russo, S., Testini, M. and Villan, M. 2002. Human anisakiasis in Italy: a report of eleven new cases. Pathol. Res. Pract. 198, 429–434. Pozio, E. 2013. Integrating animal health surveillance and food safety: the example of Anisakis. Rev. Sci. Tech. 32, 487–496. Rohlwing, T., Palm, H.W. and Rosenthal, H. 1998. Parasitation with Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda) influences the survival rate of the European smelt Osmerus eperlanus retained by a screen wall of a nuclear power plant. Dis. Aquat. Org. 32, 233–236. Silva, M. and Eiras, J. 2003. Occurrence of Anisakis sp. in fishes off the Portuguese West coast and evaluation of its zoonotic potential. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 23, 13–17. Song, H., Jung, B.K., Cho, J., Chang, T., Huh, S. and Chai, J.Y. 2019. Molecular identification of Anisakis larvae extracted by gastrointestinal endoscopy from health checkup patients in Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 57, 207. Strømnes, E. and Andersen, K., 2000. “Spring rise” of whaleworm (Anisakis simplex; Nematoda, Ascaridoidea) third-stage larvae in some fish species from Norwegian waters. Parasitol. Res. 86(8), 619–624. Unger, P., Klimpel, S., Lang, T. and Palm, H.W. 2014. Metazoan parasites from herring (Clupea harengus L.) as biological indicators in the Baltic Sea. Acta Parasitol. 59(3), 518–528. Villazanakretzer, D.L., Napolitano, P.G., Cummings, K.F. and Magann, E.F. 2016. Fish parasites: a growing concern during pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 71, 253–259. World Health Organization (WHO). 2012. Soil-transmitted helminths. World Health Organization. Available via http://www.who.int/intestinal_worms/en/ Yorimitsu, N., Hiraoka, A., Utsunomiya, H., Imai, Y., Tatsukawa, H., Tazuya, N., Yamago, H., Shimizu, Y., Hidaka, S., Tanihira, T. and Hasebe, A. 2013. Colonic intussusception caused by anisakiasis: a case report and review of the literature. Inter. Med. 52(2), 223–226. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Rahman MMIA, Elbarbary NB, Darwish WS, Mohamed RE, Abo-almagd EE, Mustafa NA, Nasr EAA. Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 Web Style Rahman MMIA, Elbarbary NB, Darwish WS, Mohamed RE, Abo-almagd EE, Mustafa NA, Nasr EAA. Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=254424 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Rahman MMIA, Elbarbary NB, Darwish WS, Mohamed RE, Abo-almagd EE, Mustafa NA, Nasr EAA. Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Rahman MMIA, Elbarbary NB, Darwish WS, Mohamed RE, Abo-almagd EE, Mustafa NA, Nasr EAA. Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 Harvard Style Rahman, M. M. I. A., Elbarbary, . N. B., Darwish, . W. S., Mohamed, . R. E., Abo-almagd, . E. E., Mustafa, . N. A. & Nasr, . E. A. A. (2025) Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 Turabian Style Rahman, Mona Mohammed I. Abdel, Noha B. Elbarbary, Wageh Sobhy Darwish, Rehab E. Mohamed, Elham Elsayed Abo-almagd, Nafissa A. Mustafa, and Elshimaa A. A. Nasr. 2025. Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 Chicago Style Rahman, Mona Mohammed I. Abdel, Noha B. Elbarbary, Wageh Sobhy Darwish, Rehab E. Mohamed, Elham Elsayed Abo-almagd, Nafissa A. Mustafa, and Elshimaa A. A. Nasr. "Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Rahman, Mona Mohammed I. Abdel, Noha B. Elbarbary, Wageh Sobhy Darwish, Rehab E. Mohamed, Elham Elsayed Abo-almagd, Nafissa A. Mustafa, and Elshimaa A. A. Nasr. "Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2774-2781. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Rahman, M. M. I. A., Elbarbary, . N. B., Darwish, . W. S., Mohamed, . R. E., Abo-almagd, . E. E., Mustafa, . N. A. & Nasr, . E. A. A. (2025) Occurrence of Anisakis spp. in fish and fish products in Egyptian markets. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2774-2781. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.45 |