| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3558-3570 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(8): 3558-3570 Research Article Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse modelTuğçe Anteplioğlu1*, Merve Bişkin Türkmen1, Erva Eser2, Damla Okatan1 and Oğuz Kul11Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kırıkkale University, Kırıkkale, Turkey 2Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kırıkkale University, Kırıkkale, Turkey *Corresponding Author: Tuğçe Anteplioğlu. Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kırıkkale University, Kırıkkale, Turkey. Email: tugceanteplioglu [at] kku.edu.tr Submitted: 29/04/2025 Revised: 30/06/2025 Accepted: 22/07/2025 Published: 31/08/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

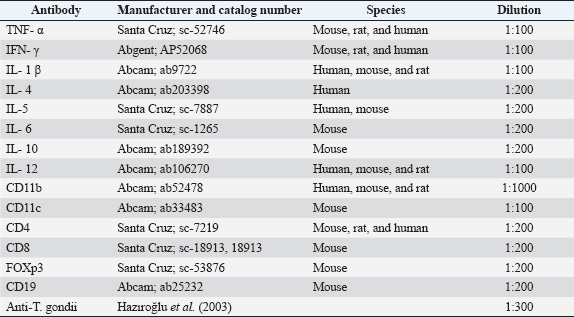

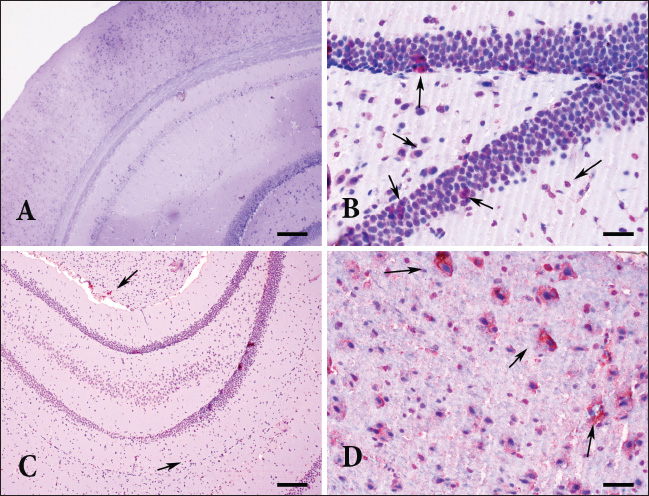

ABSTRACTBackground: Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread intracellular protozoan that can cause chronic infection in immunocompetent hosts, leading to subclinical neuroinflammation. Understanding the immunopathogenesis of chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis requires well-characterized animal models. Aim: This study aimed to evaluate infection severity, affected immune cell populations, and cytokine response in both early and late chronic phases of T. gondii infection. Methods: A murine model was developed by infecting C57BL/6 mice with a sub-infective dose (104 tachyzoites) of the ME49 strain. Forty mice were used: 30 infected and 10 controls. Animals were sacrificed on days 30, 60, and 180 after infection. Brains were analyzed using histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Results: Histopathological changes, including gliosis, meningitis, vasculitis, and neuronal degeneration, were most prominent on days 30 and 60 and decreased by day 180. Immunohistochemistry revealed dynamic changes in immune cell populations (CD4+, CD8+, CD11b+, CD11c+, CD19+, and FOXP3+) and cytokine expression (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-18). A mixed pro- and anti-inflammatory response was observed, shifting toward immunoregulation at day 180, with increased FOXP3+ cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines. PCR confirmed T. gondii DNA in all infected groups. Conclusion: This model shares several immunopathological features with chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis observed in immunocompetent humans, modeling aspects of the infection even in the absence of demonstrable tissue cysts. The immunological shift from pro-inflammatory to regulatory responses highlights the mechanisms of immune modulation and persistence. This study provides a useful platform to explore host-pathogen interactions and CNS immune dynamics in chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis. Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, Cytokine, Immunohistochemistry, Mice, Brain disease. IntroductionToxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite that can infect all warm-blooded organisms worldwide (Lindsay and Dubey, 2020). Studies have shown that 1/3 of the world’s warm-blooded animals have encountered this parasite at some point in their lives (Montoya and Liesenfeld, 2004). Toxoplasma gondii primarily infects hosts through the ingestion of sporulated oocysts—shed in the feces of felid definitive hosts—or via tissue cysts in undercooked meat (Hill and Dubey, 2002). Following oral ingestion, sporozoites or bradyzoites excyst in the gastrointestinal tract and differentiate into rapidly multiplying tachyzoites, which disseminate systemically to neural and muscular tissues. In immunocompetent individuals, the infection is typically asymptomatic or associated with mild flu-like symptoms and occasional lymphadenopathy (Montoya and Liesenfeld, 2004). However, reactivation or primary infection can trigger severe disease, including encephalitis, chorioretinitis, and congenital defects, in immunocompromised patients or fetuses. Toxoplasma gondii tissue cysts persist mainly in the central nervous system during the chronic phase, where latent infection may be associated with subtle neuropsychiatric manifestations (Akins et al., 2023). Previous studies have suggested that T. gondii may influence behavior in mice, such as reducing their aversion to cat odors (Webster, 2001; Vyas et al., 2007). Humans are an incidental intermediate host for T. gondii, and tachyzoites that reach the brain in humans undergo stage conversion and remain latent as bradyzoites for life. Studies have shown that tissue cysts disintegrate periodically and activated tachyzoites infect new cells (Tenter 2000; Weiss and Kim, 2007). In humans, chronic latent toxoplasmosis has been directly linked to increased violence, depression, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s disease (Flegr, 2007; Kusbeci et al., 2011; Pearce et al., 2014). Slowly proliferating bradyzoites can evade the host immune system and remain inside neurons for life in the latent stage. During their stay, they affect neuronal functions by inhibiting neuronal apoptosis, increasing tyrosine hydroxylase release, and stimulating cytokine response, thereby causing behavioral changes (Parlog et al., 2015). In vivo studies in transgenic mice have shown that increased levels of cytokines synthesized in the brain play an important role in the pathogenesis of neurotoxic and neurodegenerative disorders (Campbell et al., 1998). Immunopathology of cerebral toxoplasmosis is not fully understood. However, it is known that IL-12 and IFN-γ are required for the control of tissue cysts in the brain in chronic toxoplasmosis (Suzuki and Joh, 1994). CD4+ and CD8+ cells, which are involved in both cell-mediated and humoral responses, have been shown to be the source of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (Gazzinelli et al., 1992). Although pro-inflammatory IFN-γ-dependent responses are essential for immunity against toxoplasmosis, inflammatory cytokine and nitric oxide overproduction can lead to tissue damage (Gavrilescu and Denkers, 2001; Mordue et al., 2001). Astrocytes and microglia play an important role in the regulation of IFN-γ by secreting cytokines and chemokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 (Suzuki et al., 2007). This study aimed to evaluate infection severity, affected immune cell populations, and cytokine response in both early and late chronic phases of T. gondii infection. An experimental animal model resembling latent cerebral toxoplasmosis in humans was developed for this purpose. Materials and MethodsAnimalsA total of 40 specific-pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice (male, 6–8 weeks old, weighing 20–25 g) were obtained from Kobay A.Ş. (Turkey). Mice were housed in type II long and hepafiltrated cages at 20°C−23°C with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. Commercial food and water were provided ad libitum. Each experimental group consisted of 10 animals based on ethical considerations and in accordance with previous studies employing similar in vivo models (Estato et al., 2018; Eberhard et al., 2025). This number was selected to balance scientific rigor with feasibility in multi-time-point histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses. Parasite strainsThe ME49 strain (Type II), which is known to induce chronic toxoplasmosis in murine models (Ferguson, 2004), was obtained as tachyzoites from Dr Alvaro Freyre McCall, Laboratorio De Toxoplasmosis, and maintained by passage in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicilin-streptomycin (Gibco). The tachyzoites were incubated at 37°C and 4% CO2 and grown until the number of sufficient tachyzoites was determined. The tachyzoites were then detached from the Vero cells by passing them through a 25-gauge needle, separated from most of the cell debris using a 3-μm pore size filter, and resuspended in sterile physiological saline. Infection modelWhile higher doses (105–106 tachyzoites) are commonly used in acute models of toxoplasmosis (Dubey, 2008), a lower dose of 104 tachyzoites was chosen in this study to simulate a subclinical and slowly developing chronic infection. The mice were then randomly divided into three groups of 10 mice each. In the control group, 10 mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with sterile saline. After inoculation, mice were observed regularly until euthanasia. No acute signs of disease were observed in any of the mice, and none of them died before euthanasia. HistopathologyMice were sacrificed by CO2 euthanasia cabinet on days 30, 60, and 180 after infection, and their brains were collected. Brains were fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde solution for 48 hours, embedded with paraffin wax, and sectioned coronally at a thickness of 4 µm coronally. Sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and overslipped with entella. Slides were examined by light microscopy (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan), and photomicrographs were taken using a DP25 camera (Japan). According to Hermes et al. (2008), the severity of lesions was scored as follows: 1: mild, 2: moderate, 3: severe. All analyses were performed at 40× magnification (Hermes et al., 2008). ImmunohistochemistryAntibodyThe primary antibodies used in this study, along with their manufacturers, catalog numbers, host species, and working dilutions, are summarized in Table 1. ImmunohistochemistryAll immunohistochemical analyses were performed using a commercial immunoperoxidase kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), AEC chromogen, and Mayer’s hematoxylin for counterstaining. The same procedures were used for the negative control, but normal mouse serum was used instead of the primary antibody. Mouse tissues infected with T. gondii from previous studies were used as a positive control. Sections were deparaffinised in three series of xylol for 5 minutes each and rehydrated in absolute alcohol, 95% and 70% alcohol, and distilled water for 5 minutes each. Tissues were boiled in citrate solution (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes for antigen retrieval. The cells were then treated with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were then incubated for 10 minutes with protein blocking serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) for 10 minutes. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies (anti-TNF-α, anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-1β, anti-IL-4, anti-IL-10, anti-IL-12, anti-GFAP, anti-S100, anti-CD11b, anti-CD11c, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-FOXP3, anti-CD19 and anti-T. gondii) (Table 1) overnight at +4°C. Sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies and streptavidin-peroxidase enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, stained with AEC chromogen and Mayer’s hematoxylin, and sealed with a water-based adhesive. Staining was evaluated, and microphotographs were taken using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Japan) with a DP25 camera attachment. Table 1. Primary antibodies

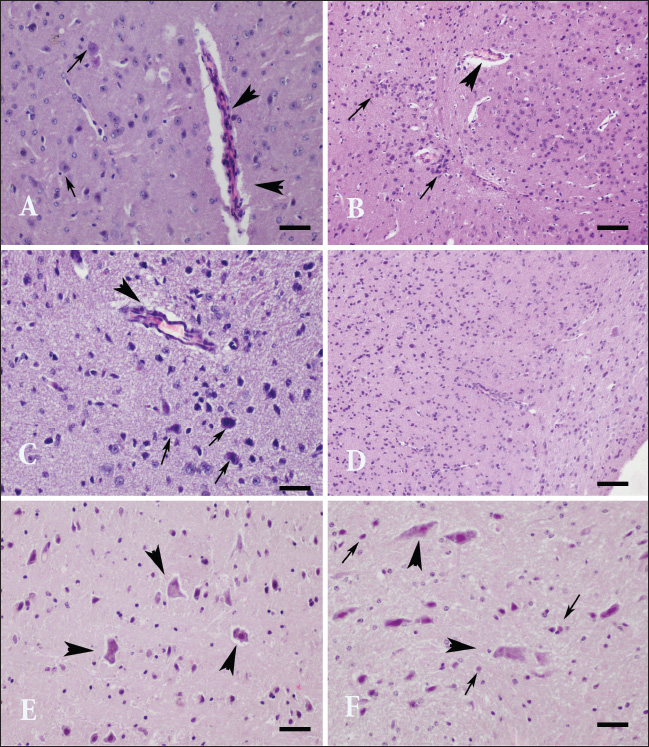

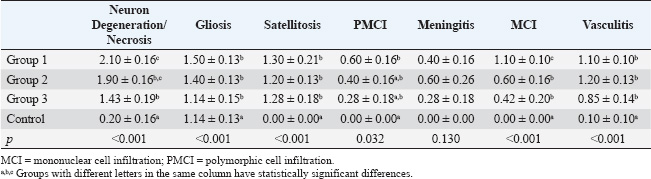

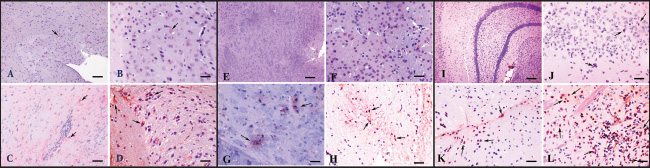

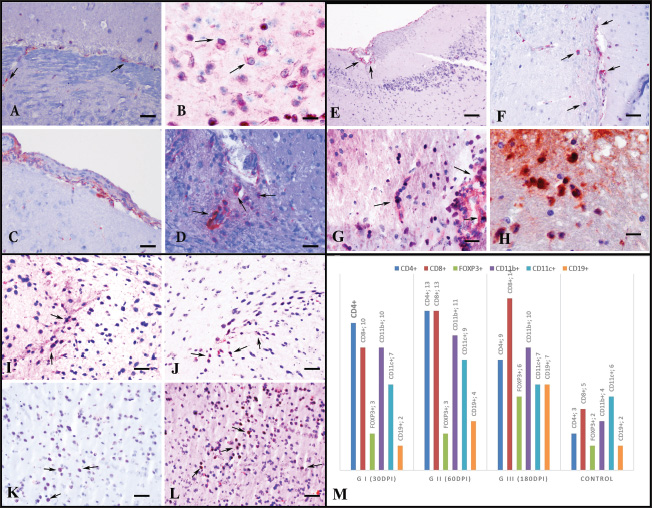

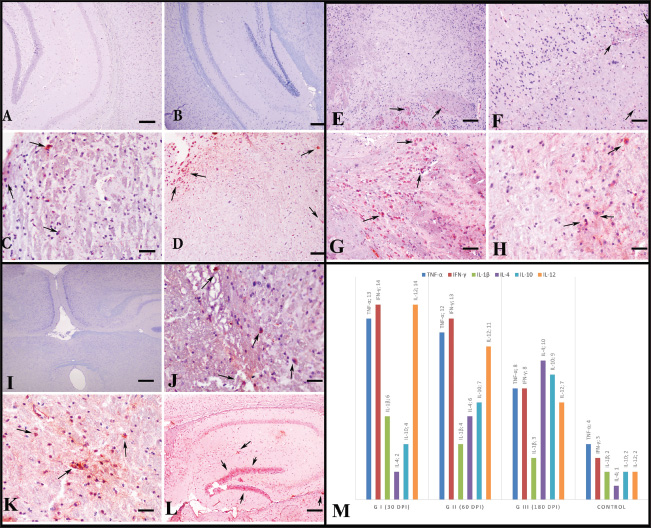

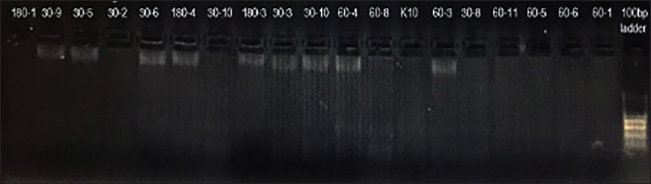

Toxoplasma gondii-specific polymerase chain reactionThe B1 gene, which has 35 copies in the T. gondii genome, is used for the rapid and sensitive diagnosis of toxoplasmosis (Lin et al., 2000; Buchbinder et al., 2003). Therefore, in this study, after isolating DNA from each brain sample according to the protocol of the High Pure polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Preparation Kit (Roche Applied Sciences, Germany), nested PCR was used to identify the B1 gene of T. gondii (GenBank No. AF179871). The first primers, 5_-TCAAGCAGCGTATTGTCGAG-3_ [20 nucleotides (nt), oligo 1, forward primer] and 5_-CCGCAGCGACTTCTATCTCT-3_ (20 nt, oligo 2, reverse primer), were amplified in the first reaction. The second nested PCR reaction amplified the 194 base pair gene fragments, 5_-GGAACTGCATCCGTTCATGAG-3_ (21 nt, N1, forward primer) and 5_-TCTTTTAAAGCGTTCGTGGTC-3 (20 nt, C1, reverse primer). Of the first 50 l of amplified reaction volume, 25 l consisted of purified DNA template, 1 _M primers of GoTaq DNA polymerase (oligo 1 and oligo 2), 1.25 U (5 U/_L; Promega, United States), 1_ GoTaq reaction buffer (Promega), and 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (Invitrogen, United States). PCR amplification reactions consisted of a denaturation step at 94°C for 30 seconds, followed by 50 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 45°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds, followed by a binding step at 72°C for 10 minutes. The second 50 l of amplification reactions consisted of 1 l of the initial PCR reaction products, 1.25 U GoTaq DNA polymerase, 0.2 _M primers (C1 and N1), (5 U/_L), 1_ GoTaq reaction solution, and 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate. PCR amplification reactions were performed as a denaturation step at 94°C for 30 seconds, followed by 50 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 45°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds, and finally a binding step at 72°C for 10 minutes. PCR products were visualized by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Statistical analysesAfter scoring for histopathological changes (neuronal degeneration/necrosis, gliosis, satellitosis, perivascular cell infiltration, meningitis, focal mononuclear cell infiltration, and vasculitis), one-way analysis of variance was performed in accordance with the data distribution. The distribution of antibody types within the tissues was evaluated by two-way analysis of variance when the immune test results were analyzed. In both analyses, the Tukey test was used to determine the differences between the groups. Statistical evaluations were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1. Ethical approvalAnimal husbandry and experimental procedures were performed at the Hüseyin Ayremiz Laboratory Animal Facility and Research Center of Kırıkkale University. All experimental procedures and stages were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Kırıkkale University (Number of Ethics Committee Report: 16/23, 02.25.2016). ResultsHistopathologic findingsThe brains of the infected mice were macroscopically normal. However, microscopy revealed neuronal degeneration and necrosis, gliosis, satellitosis, perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrations, non-purulent meningitis and vasculitis, and capillary endothelial hypertrophy in infected brains. These lesions were mainly located in the cerebral cortex, thalamus, caudate-putamen (striatum), amygdala, hippocampus, and substantia nigra regions of the brain, whereas lesions in the cerebellum were found only in the group sacrificed on day 180. On days 30 and 60, the histopathological changes observed in the sacrificed groups were similar to each other, whereas milder neuropathological changes were observed in the group sacrificed on day 180 compared to the others. However, no tissue cysts were observed in any group (Fig. 1, Table 2). Immunoperoxidase findingsWhile no immunoreaction to T. gondii antigen was observed in the control group, all other groups exhibited moderate to severe immunopositivity, particularly in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, striatum, and substantia nigra (Fig. 2A–D). Strong immunopositivity was found in the hippocampus pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2B), glial cells, and astrocytes in the SN (Fig. 2C), and degenerated neurons and astrocytes in the amygdala (Fig. 2D). Mild to moderate immunoreactivity was observed in other regions. In addition, gliosis and mononuclear cell infiltration were observed in regions with infected cells. Two-way analysis of variance was used to evaluate the differences between groups for T. gondii antigen, cytokine expressions (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-18), and cell populations (CD4+, CD8+, FOXP3+, CD11b+, CD11c+, CD19+) evaluated in immunohistochemical tests. When each brain region was evaluated separately, statistically significant differences were found between the cortex and the striatum (p=0.002), amygdala (p=0.001), and substantia nigra (p=0.049), whereas no significant differences were observed between the cortex and other regions, such as the thalamus (p=0.869), hippocampus (p=0.441), and VTA (p=0.999). Although the inflammatory cell population in group K was much lower than in the other groups, the amount of B lymphocytes was similar to that in group I. The presence of CD4+ cells was the most frequent in group II. Although the CD4+ and CD8+ cell densities were similar in group II, the CD8+ cells were most frequently observed in group III. The level of FOXP3+ cells was quite low in all groups except group III. CD11b+ and CD11c+ cells were found in almost equal amounts in all groups except the control group (Fig. 4). M). CD4+ cells were found in almost all brain regions in groups I and II, whereas they were mainly found in the striatum, amygdala, and ventral tegmental area in group III (Fig. 4A–D). CD8+ cells were more abundant in the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra in all groups (Fig. 4E–H), whereas CD11b+ and CD11c+ cell densities were higher in the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and basal part of the brain (Fig. 3A–H). The FOXP3+ cell population was also more concentrated in the ventral tegmental area and SN (Fig. 4I–L). It was observed that pro-inflammatory cytokine expressions of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12 decreased over time from Groups I to III, whereas the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 increased. Furthermore, IL-1β and IL-18 from the same group were found to be the highest in Group I and lowest in Group III (Fig. 6M). The highest expressions of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12 were observed in the cerebral cortex, striatum, and amygdalar region of the brain in all groups except the control group (Fig. 5). Furthermore, IL-5 and IL-6 were expressed from the same cells in almost the same regions and at similar rates (Figs. 5 and 6). IL-4 and IL-10 were predominantly expressed in the midbrain (Fig. 6). Toxoplasma gondii-specific PCRThe B1 gene, which is specific for T. gondii, was negative in the control group but positive in all infected groups, thus confirming the immunohistochemical findings (Fig. 7). DiscussionAlthough T. gondii can cause various pathologies in infected humans, humans are considered terminal hosts that are not essential for the parasite’s life cycle (Tenter et al., 2000). In contrast, mice serve as intermediate hosts in which the parasite manipulates host behavior by reducing fear responses to ensure its own transmission (Vyas et al. 2007). However, studies in mice have shown that tissue cysts are mostly located in the amygdala. Toxoplasma gondii has two genes encoding tyrosine hydroxylase, which causes neurodegenerative changes after neuronal invasion and induces neuroinflammation, all of which are thought to contribute to behavior modulation (Vyas et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2007; Gaskell et al., 2009; Hunter and Sibley 2012; Haroon et al., 2012). In contrast, evidence for intracerebral tissue cysts in immunocompetent humans is quite limited (Pusch et al., 2009). Although behavioral changes have been reported in other T. gondii models, this study focused solely on neuropathological and immunological parameters. The statistical strength and regional consistency of the findings (p < 0.001) validate the reliability of the observed immune dynamics across time points.

Fig. 1. Neurohistopathological changes in groups I, II, and III. (A) The amygdala region. Vasculitis and endothelial hypertrophy with neuronal degeneration (arrow) in group I, HE; Bar=100 µm (B) Striatum. Focal mononuclear cell infiltration (arrowhead) in group I, HE staining. Bar=200 µm. (C) Thalamus. Vasculitis and mild perivascular cell infiltration (arrowhead), neuronal degeneration, and necrosis (arrow) in group II, HE, bar=100 µm. (D) Cerebral cortex. Foci of vasculitis, perivascular cell infiltration, neuronal degeneration, and gliosis in group II, HE, bar=200 µm. (E) Amygdala. Eosinophilic, necrotic neurons with lost nuclei in group III (arrowhead), HE staining, bar=100 µm. (F) Ventral tegmental area. Degenerated and necrotic neurons in group III (arrowhead), microglia activation (arrow), HE staining, Bar=100 µm. Table 2. Histopathological findings (mean ± SE).

Fig. 2. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii specific antigens in all groups AEC chromogen and Mayer’s hematoxylin counterstain (A) Hippocampus and neocortex. Control group, no immunoreactivity, bar=200µm (B) Hippocampus. Group I, moderate immunopositive reaction in neurons, bar=100µm (C) Sub. nigra and hippocampus. The moderate immunopositive reaction in group II, Bar=200 µm (D) Amygdala. The strong immunopositive reaction in neurons and astrocytes in group III. Scale bar=100 µm. Therefore, in this study, to mimic the infection in immunocompetent individuals, bradyzoites—known to be less infectious than oocysts in intermediate hosts—were administered at a sub-infective dose (104) in C57BL/6 mice to induce chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis. The infected mice developed neuropathological and immunological features that resemble aspects of chronic encephalitic toxoplasmosis observed in immunocompetent individuals. Although no tissue cysts were observed, findings such as neuronal degeneration and necrosis, gliosis, satellitosis, focal mononuclear cell infiltrates, non-purulent meningitis, and vasculitis were present. Toxoplasma gondii immunopositivity was detected in these affected regions, and PCR confirmed the presence of the B1 gene. The affected regions were mapped on days 30, 60, and 180 post-infection, and a general pathogenesis profile was established by identifying the expressed cytokines and the immune cells involved. Considering the correlation between human and mouse aging, true chronic infection was determined to begin after day 60.

Fig. 3. Immunoreactivity of CD11b+ (A-D), CD11c+ (E-H), and CD19+ (I-L) cells according to groups, AEC chromogen, and Mayer’s hematoxylin counterstaining. (A) Substantia nigra. Control group, mild immunopositivity, bar=200 µm. (B) Cerebral cortex. Group I, moderate immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (C)Striatum. Mild immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=200 µm. (D) Severe immunopositive reaction in Group III, bar=200µm. (E) Midbrain Group C, very mild immunopositivities, bar=200µm. (F) Cerebral cortex. Group I, moderate immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (G) Striatum. Mild immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (H) Ventral tegmental area. Moderate immunopositive reaction in group III, bar=200µm. (I) Hippocampal area in the control group, very mild immunopositivities, bar=200µm. (J) Hippocampus in group I, moderate immunopositive reaction, bar=100µm. (K) Striatum. Mild immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (L) Substantia nigra. The moderate immunopositive reaction in group III (bar=100 µm. Notably, recent studies have shown that as T. gondii infection progresses into the late chronic phase, parasite burden—including tissue cysts and even detectable DNA—may diminish significantly in the CNS. McGovern et al. (2020) reported the complete absence of histologically visible cysts, parasite DNA, and inflammation in mice at 20 months post-infection, despite prior confirmation of brain infection. The absence of tissue cysts at 180 days in our model may reflect a similar trend of declining parasite burden over time. Given that parasite DNA and antigen positivity were still detectable at day 180, future long-term studies are needed to determine whether these markers persist or gradually diminish as the infection progresses further into the chronic phase. Chronic toxoplasmosis is often established in experimental models using higher doses of tissue cysts, which may not reflect the natural course of infection. The lower dose used in this study was chosen to replicate subclinical infection patterns in humans. This approach may account for the absence of histologically visible cysts. Furthermore, several human studies have reported that brain cysts are rarely detected in immunocompetent individuals, even in the context of confirmed chronic infection (Pusch et al., 2009), suggesting that cyst burden may fall below the detection threshold. Thus, the lack of observable cysts does not preclude the establishment of chronic infection, which was supported in our model by parasite persistence (immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction) and a time-dependent shift toward regulatory immune responses. Since the discovery of T. gondii, numerous in vitro and in vivo experimental studies have been conducted to understand the host-parasite interaction and the host’s immune responses (Hokelek et al., 2002; Meylan et al., 2006; Dupont et al., 2012). Most immunopathogenesis studies have focused on individual immune cell types, small groups of cytokines, or direct damage caused by the parasite (Giri et al., 1994; Gazzinelli et al., 1992; Suzuki et al., 2005; Parlog et al., 2015; Haroon et al., 2012). In the present study, chronic encephalitic toxoplasmosis was established using the type II ME49 strain, and nine cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and IL-18) and six immune cell types (CD4+, CD8+, FoxP3+, CD11b+, CD11c+, and CD19+ cells) were analyzed. FOXP3+ T cells have been suggested to mitigate inflammation, although the mechanisms remain unclear (Lowther and Hafler, 2012), and their role in CNS infections is still not well understood (O’Brien et al., 2017). In this study, the FOXP3+ population was significantly increased in Group III compared with that in Groups I and II and the control. This increase, along with elevated CD8+ T cells and higher IL-10 and IL-4 expression in Group III, suggests a compensatory immunoregulatory response. The same regions (cerebral cortex, thalamus, amygdala, VTA, and substantia nigra) where FOXP3+ cells were found also showed increased IL-10 and IL-4 expression. Moreover, the decrease in CD4+ T cells in Group III compared with those in Groups I and II supports the hypothesis that FOXP3+ cells may replace CD4+ Th1 cells in the advanced chronic phase.

Fig. 4. Immunoreactivity of CD4+ (A-D), CD8+ (E-H), and FOXP3+ (I-L) cells according to groups. AEC chromogen and Mayer’s hematoxylin counterstaining of (A) Striatum. Control group, mild immunopositivity, bar=100µm. (B) Amygdala. Group I, moderate immunopositive reaction, bar=50µm. (C) Cerebral cortex. Moderate immunopositive reaction of vessel wall-integrated CD4+ cells in the meninges and vessel wall in group II, Bar=100 µm. (D) Ventral tegmental area. Moderate immunopositive reaction in Group III, Bar=100 µm. (E) Hippocampal fissure. Control group, mild immunopositivity, bar=200 µm. (F) Caudate. Group I, mild immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (G) Thalamus. Moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (H) Substantia nigra. Severe immunopositive reaction in group III, bar=50 µm. (I) Striatum. Group C, mild immunopositivity, bar=100 µm. (J) Cerebral cortex. Group I, mild immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (K) Thalamus. Mild immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (L) Thalamus. Moderate immunopositive reaction in group III, bar=100 µm. (M) Immune cell distribution in the CNS according to their immunoreactivity. IL-5 and IL-6 were also detected in overlapping brain regions during this late phase. Their moderate expression, particularly in areas enriched with FOXP3+ cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines, may reflect a broader Th2-skewed immune shift supporting immune regulation and tissue preservation in the chronic stage. Toxoplasma gondii infection stimulates IL-12 production, which activates T lymphocytes to release IFN-γ and TNF-α (Hunter et al., 1994). In this context, the higher CD4+ population in Group I, particularly in the cerebral cortex, striatum, thalamus, amygdala, and ventral tegmental area, correlates with increased parasite presence and elevated IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels. TNF-α and IFN-γ help suppress and eliminate the parasite (Sibley et al., 1991; Gazzinelli et al., 1994; Andrade et al., 2006). However, despite a strong Th1 cytokine response, histopathological damage still progressed, which is consistent with the hypothesis that these cytokines alone are insufficient for complete protection.

Fig. 5. Immunoreactions of IFN-γ (A-D), TNF-α (E-H), IL-12 (I-L), IL-1β (M-P), IL-6 (R-U), and IL-18 (X-Z) according to groups and brain regions. AEC chromogen and Mayer’s hematoxylin counterstaining. (A) Hippocampus. AEC chromogen, AEC chromogen. Control group, mild immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (B) Cerebral cortex. Group I, severe immunopositive reaction; Bar=200 µm. (C) Striatum. The moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (D) Amygdala. Moderate immunopositivity in group III, bar=100 µm. (E) Thalamus. Control group, mild immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (F) Cerebral cortex. Group I, severe immunopositive reaction, bar=200 µm. (G) Cerebral cortex. Severe immunopositive reaction in group II, Bar=100 µm. (H) Neocortex. Severe immunopositive reaction in neurons and astrocytes in Group III. Scale bar=200 µm. (I) Cerebral cortex. Control group, mild immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (J) Substantia nigra. Group I, severe immunopositive reaction, bar=100 µm. (K) Ventral tegmental area. The moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=200 µm. (L) Thalamus. Mild immunopositivity in group III, bar=200 µm. (M) Hippocampus. Control group, no immunoreactivity; bar=100 µm. (N) Striatum. Group I, moderate immunopositive reaction, bar=200 µm. (O) Ventral tegmental area. Moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=200 µm. (P) Substantia nigra. Mild immunopositivity in Group III, bar=200 µm. (R) Hippocampal region. Control group, no immune reactivity; bar=400 µm. (S) Hippocampal region. Group I, mild immunopositive reactivity; bar=400 µm. (T) Striatum. The moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=200 µm. (U) Amygdala. Moderate immunopositivity in Group III, Bar=100 µm. (X) Brain. Control group, no immunoreactivity, bar=400 µm. (V) Neocortex. Group I, moderate immunopositive reaction, bar=200 µm. (Y) Hypothalamus. Moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (Z) Cerebral cortex. Mild immunopositivity in group III, bar=100 µm.

Fig. 6. Immunoreactions of IL-4 (A-D), IL-5 (E-H), and IL-10 according to groups and brain regions. AEC chromogen and Mayer’s hematoxylin counterstaining. (A) Hippocampal region. No immunoreactivity in the control group. Bar=200 µm. (B) Hippocampal region. No immunoreactivity in group I. Bar=200 µm. (C) Amygdala. The moderately immunopositive reaction in Group II, bar=100 µm. (D) Substantia nigra. Moderate immunopositivity in Group III, Bar=200 µm. (E) Hypothalamus. Control group, mild immunopositive reactivity; bar=200 µm. (F) Hippocampal region. Group I, mild immunopositive reactivity; Bar=200 µm. (G) Hypothalamus. Severe immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=100 µm. (H) Thalamus. Moderate immunopositivity in Group III. Scale bar=400 µm. (I) Brain Control group, no immunoreactivity, bar=400 µm. (J) Ventral tegmental area. Group I, mild immunopositive reactivity; Bar=100 µm. (K) Thalamus. Moderate immunopositive reaction in Group II, Bar=200 µm. (L) Hippocampal region. Mild immunopositivity in group III, bar=400 µm. (M) Distribution of cytokines expressed during T. gondii infection in the brain according to their immunoreactivity. Group II, which represents day 60 of infection, showed the highest levels of both innate (CD11b+, CD11c+, CD4+ Th1) and adaptive (CD4+, CD8+ Th2) immune cells. Therefore, this time point may reflect a transitional subacute phase rather than a fully developed chronic infection. However, most chronic studies end at or before this point (Ferguson et al., 1994; Mohle et al., 2014; Hwang et al., 2018). Although this may be suitable for latent toxoplasmosis with cyst formation, it may not effectively model encephalitic toxoplasmosis in humans. Thus, the 180-day chronic group in this study gains importance. Tachyzoite numbers decreased by day 180 compared to day 30, but immune responses—including CD8+, FOXP3+, and CD19+ cell populations and their associated cytokines—remained elevated. This suggests an asymptomatic chronic phase with sustained immune vigilance, possibly preparing the central nervous system for reactivation or reinfection. Given that T. gondii manipulates mice to reduce fear of cats to complete its life cycle (Vyas et al., 2007), the parasite may maintain a standby immune response in humans to prevent fatal outcomes that would halt its transmission cycle.

Fig. 7. Agarose gel electrophoresis showing nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the Toxoplasma gondii B1 gene (194 bp). Lane labels correspond to brain tissue samples collected on days 30, 60, and 180 post-infection (e.g., 30-5, 60-8, 180-1). Clear bands at ~194 bp confirm the presence of T. gondii DNA in infected mice. Lanes marked with “K” represent uninfected control mice (negative controls). Lane on the far right: 100-bp DNA ladder. Other studies have shown that IL-1β can induce the differentiation of mesencephalic progenitors into dopaminergic neurons in rats, possibly contributing to schizophrenia (Kabiersch et al., 1998; Potter et al., 1999). In clinical cases of chronic toxoplasmosis linked with psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and anxiety, elevated IL-1β levels have been detected (Soderlund et al., 2011). IL-1β, like TNF-α, plays a role not only in the early innate immune response but also in later infection stages (Hunter et al., 1992). However, a significant reduction in IL-1β expression was found between Groups I and III, especially on day 180. ConclusionIn conclusion, this study highlights the dynamic and evolving immune response in chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis and suggests that although a strong Th1 response is activated during the early stages of infection, it may not be sufficient to prevent CNS pathology in the absence of effective regulatory control. The late-stage dominance of regulatory and adaptive immune elements, particularly FOXP3+ and CD8+ T cells, along with increased IL-10 and IL-4 expression, indicates an immunomodulatory shift aimed at balancing host protection with inflammation control. Although the present study is descriptive in nature, the detailed temporal mapping of cytokine and immune cell dynamics provides a valuable framework for future mechanistic studies that aim to elucidate causal pathways in chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis. Together, these findings offer novel insights into host-parasite interactions and reinforce the importance of long-term in vivo models for understanding persistent central nervous system infections. Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results. FundingThis work was supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Kırıkkale University. Project number: 2016/040. Authors’ contributionsTA: Conceptualization, supervision, and writing of the original draft. MBT: formal analysis. EE: Statistical analysis. DO: Investigation and validation. OK: Resources, review, and editing. Data availabilityThe data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. ReferencesAkins, G.K.H., Furtado, J.M. and Smith, J.R. 2023 Diseases caused by and behaviors associated with Toxoplasma gondii infection. Pathogens 12, 627. Andrade, R.M., Wessendarp, M., Gubbels, M.J., Strıepen, B. and Subauste, C.S. 2006. CD40 induces macrophage anti-Toxoplasma gondii activity by triggering autophagy-dependent fusion of pathogen-containing vacuoles and lysosomes. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2366–2377; doi:10.1016/j.jci.2016.09.002 Buchbinder, S., Blatz, R. and Rodloff, A.C. 2003. Comparison of real-time PCR detection methods for B1 and P30 genes of Toxoplasma gondii. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45, 269–271. Campbell, I.L., Stalder, A.K., Akwa, Y., Pagenstecher, A. and Asensio, V.C. 1998. Transgenic models to study the actions of cytokines in the central nervous system. Neuroimmunomodulation 5(3-4), 126–135. Dubey, J.P. 2008. The history of Toxoplasma gondii—The first 100 years. Vet. Parasitol. 163, 184–195; doi:10.1016/j.vppara.2016.01.013 Dupont, C.D., Christian, D.A. and Huntrer, C.A. 2012. Immune response and immunopathology during toxoplasmosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 34(6), 793–813. Eberhard, J.N., Shallberg, L.A., Winn, A., Chandrasekaran, S., Giuliano, C.J., Merritt, E.F., Willis, E., Konradt, C., Christian, D.A., Aldridge, D.L., Bunkofske, M.E., Jacquet, M., Dzierszinski, F., Katifori, E., Lourido, S., Koshy, A.A. and Hunter, C.A. 2025. Immune targeting and host-protective effects of Toxoplasma gondii at the latent stage. Nat. Microbiol. 10, 992–1005. Estato, V., Stipursky, J., Gomes, F., Mergener, T.C., Frazão-Teixeira, E., Allodi, S., Tibiriçá, E., Barbosa, H.S. and Adesse, D. 2018. The neurotropic parasite Toxoplasma gondii induces sustained neuroinflammation with microvascular dysfunction in infected mice. Am. J. Pathol. 188(11), 2674–2687. Ferguson, D.J.P. 2004. Use of mice in models of chronic toxoplasmosis. J. Comp. Pathol. 130, 91–95. Ferguson., DJ., Huskınson-Mark, J., Araujo, F.G. and Remington, J.S. 1994. A morphological study of chronic cerebral toxoplasmosis in mice: comparison of four different strains of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Res. 80, 493–501. Flegr, J. 2007. Effects of Toxoplasma on human behavior. Schizophr. Bull. 33, 757–760. Gaskell., EA., Smıth., JE., Pınney., JW., Westhead, D.R. and Mcconkey, G.A. 2009. A unique dual activity amino acid hydroxylase in Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS One 4, 4801. Gavrilescu, L.C. and Denkers, E.Y. 2001. IFN-γ overproduction and high level apoptosis are associated with high but not low virulence Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Immunol. 167(2), 902–909. Gazzinelli, R., Xu., Y., Hıny, S. and Cheever A Sher. 1992. Simultaneous depletion of CD4_ and CD8_ T lymphocytes must reactivate chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 149, 175–180; doi:10.1016/j.jimmunol.2015.01.015 Gazzinelli, R.T., Hayashi, S., Wysocka, M., Carrera, L., Kuhn, R., Muller, W. and Sher, A. 1994. Role of IL-12 in the initiation of cell mediated immunity by Toxoplasma gondii and its regulation by IL-10 and nitric oxide. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 41(5), 9S. Giri, J.G., Ahdieh, M., Eisenman, J., Shanebeck, K., Grabstein, K., Kumaki, S. and Anderson, D. 1994. Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 13(12), 2822. Haroon, F., Händel, U., Angenstein, F., Goldschmidt, J., Kreutzmann, P., Lison, H., Fischer, K.D., Scheich, H., Wetzel, W., Schlüter, D. and Budinger, E. 2012. Toxoplasma gondii actively inhibits neuronal function in chronically infected mice. PLoS One 7(4), 35516. Hazıroğlu, R., Altıntaş, K., Atasever, A., Gülbahar, M.Y., Kul, O. and Tunca, R. 2003. Pathological and immunohistochemical studies in rabbits experimentally infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 27, 285–293. Hermes, G., Ajioka, J.W., Kelly, K.A., Mui, E., Roberts, F., Kasza, K., Mayr, T., Kirisits, M.J., Wollmann, R., Ferguson, D.J. and Roberts, C.W. 2008. Neurological and behavioral abnormalities, ventricular dilatation, altered cellular functions, inflammation, and neuronal injury in brains of mice due to common, persistent, parasitic infection. J. Neuroinflammation 5, 1. Hill, D. and Dubey, J.P. 2002. Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infections 8, 634–640. Hokelek, M., Kul, O., Altıntaş, K. and Hazıroğlu, R. 2002. Deneysel toxoplasmosiste patolojik bulgular. T. Parazitol. Derg. 26, 17–19. Hunter, C.A., Roberts, C.W., Murray, M. and Alexander, J. 1992. Detection of cytokine mRNA in the brains of mice with toxoplasmic encephalitis. Parasite Immunol. 14, 405–413. Hunter, C.A., Subauste, C.S., Van Cleave, V.H. and Remington, J.S. 1994. Production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells from Toxoplasma gondii-infected SCID mice: regulation by interleukin-10, interleukin-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 62, 2818–2824; doi:10.1016/j.immun.2012.09.016 Hunter, C.A. and Sıbley, L.D. 2012. Modulation of innate immunity by Toxoplasma gondii virulence effectors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 766–778. Hwang, Y.S., Shin, J.H., Yang, J.P., Jung, B.K., Lee, S.H. and Shin, E.H. 2018. Characteristics of infection immunity regulated by Toxoplasma gondii to maintain chronic infection in the brain. Front. Immunol. 5, 158. Montoya, J.G. and Liesenfeld, O. 2004. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 363(1965–1976), 1965–1976. Kabıersch, A., Furukawa, H., Del Rey, A. and Besedovsky, H.O. 1998. Administration of interleukin-1 at birth affects dopaminergic neurons in adult mice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 840, 123–127. Kusbeci, O.Y., Miman, O., Yaman, M., Aktepe, O.C. and Yazar, S. 2011. Could Toxoplasma gondii have any role in Alzheimer disease?. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 25, 1–3. Lin, M.H., Chen, T.C., Kuo, T.T., Tseng, C.C. and Tseng, C.P. 2000. Real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38(11), 4121–4125. Lindsay, D.S. and Dubey, J.P. 2020. Toxoplasmosis in wild and domestic animals. Toxoplasmosis in animals and humans. 3rd Edition. Ed., Dubey, J.P. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, pp: 293–320. Lowther, D.E. and Hafler, D.A. 2012. Regulatory T cells in the central nervous system. Immunol. Rev. 248, 156–169; doi:10.1016/j.immunol.rev.2018.01.013 Matowicka-Karna, J., Dymicka-Piekarska, V. and Kemona, H. 2009. Does Toxoplasma gondii infection affect the levels of IgE and cytokines (IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and TNF‐alpha)?. J. Immunol. Res 1(1), 374696. McGovern, K.E., Cabral, C.M., Morrison, H.W. and Koshy, A.A. 2020. Aging with Toxoplasma gondii results in pathogen clearance, inflammation resolution, and minimal learning and memory consequences. Sci. Rep. 10, 7979. Meylan, E., Tschopp, J. and Karın, M. 2006. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature 442, 39–44. Mohle, L., Parlog, A., Pahnke, J. and Dunay, I. 2014. Spinal cord pathology in chronic experimental Toxoplasma gondii infection. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 4, 65–75. Mordue, D.G., Monroy, F., La Regina, M., Dinarello, C.A. and Sibley, L.D. 2001. Acute toxoplasmosis leads to lethal overproduction of Th1 cytokines. J. Immunol. 167(8), 4574–4584. O’Brien, C.A., Overall, C., Konradt, C., O’hara Hall, A.C., Hayes, N.W., Wagage, S. and Harris, T.H. 2017. CD11c-expressing cells affect regulatory T cell behavior in the meninges during central nervous system infection. J. Immunol. 198(10), 4054–4061. Parlog, A., Schlüter, D. and Dunay, I.R. 2015. Toxoplasma gondii‐induced neuronal alterations. Parasit. Immunol. 37(3), 159–170. Pearce, B.D., Kruszon-Moran, D. and Jones, J.L. 2014. The association of Toxoplasma gondii infection with neurocognitive deficits in a population-based analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 49, 1001–1010. Potter, E.D., Ling, Z.D. and Carvey, P.M. 2019. Cytokine-induced conversion of mesencephalic-derived progenitor cells into dopamine neurons. Cell Tissue Res. 296(2019), 235–246; doi:10.1016/j.ctissueres.2019.03.002 Pusch, L., Romeike, B., Deckert, M. and Mawrin, C. 2009. Persistent Toxoplasma bradyzoite cysts in the brain: incidental finding in an immunocompetent patient without toxoplasmosis evidence. Clin. Neuropathol. 28, 210–212. Sıbley, L.D., Adams, L.B., Fukutomı, Y. and Krahenbuhl, J.L. 2019. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha triggers antitoxoplasmal activity of IFN-gamma primed macrophages. J. Immunol. 147, 2340–2345. Söderlund, J., Olsson, S.K., Samuelsson, M., Walther-Jallow, L., Johansson, C., Erhardt, S. and Engberg, G. 2011. Elevation of cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-1β in bipolar disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 36(2), 114–118. Suzuki, Y. and Joh, K. 1994. Effect of the strain of Toxoplasma gondii on the development of toxoplasmic encephalitis in mice treated with antibody to interferon-gamma. Parasitol. Res. 80, 125–130. Suzuki, Y., Claflın, J., Wang, X., Lengı, A. and Kikuchı, T. 2005. Microglia and macrophages as innate producers of interferon-gamma in the brain following infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 35, 83–90. In: Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan—erspectives and methods. Eds., Weiss, L.M. and Kim, K. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp: 567–591. Tenter, A.M., Heckeroth, A.R. and Weiss, L.M. 2000. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 30(12–13), 1217–1258. Vyas, A., Kim, S.K., Giacomini, N., Boothroyd, J.C. and Sapolsky, R.M. 2007. Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104(15), 6442–6447. Webster, J.P. 2001. Rats, cats, people and parasites: the impact of latent toxoplasmosis on behavior. Microbes. Infect. 3(12), 1037–1045. In: Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan—perspectives and methods. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp: 341–366. Wong, D., Dorovını-Zıs, K. and Vincent, S.R. 2007. Cytokines, nitric oxide, and cGMP modulate the permeability of an in vitro model of the human blood-brain barrier. Exp. Neurol. 190, 446–455; doi:10.1016/j.exnu.2007.04.010 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Anteplioğlu T, Turkmen MB, Eser E, Okatan D, Kul O. Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 Web Style Anteplioğlu T, Turkmen MB, Eser E, Okatan D, Kul O. Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=255173 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Anteplioğlu T, Turkmen MB, Eser E, Okatan D, Kul O. Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Anteplioğlu T, Turkmen MB, Eser E, Okatan D, Kul O. Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(8): 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 Harvard Style Anteplioğlu, T., Turkmen, . M. B., Eser, . E., Okatan, . D. & Kul, . O. (2025) Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. Open Vet. J., 15 (8), 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 Turabian Style Anteplioğlu, Tuğce, Merve Bişkin Turkmen, Erva Eser, Damla Okatan, and Oğuz Kul. 2025. Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 Chicago Style Anteplioğlu, Tuğce, Merve Bişkin Turkmen, Erva Eser, Damla Okatan, and Oğuz Kul. "Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Anteplioğlu, Tuğce, Merve Bişkin Turkmen, Erva Eser, Damla Okatan, and Oğuz Kul. "Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model." Open Veterinary Journal 15.8 (2025), 3558-3570. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Anteplioğlu, T., Turkmen, . M. B., Eser, . E., Okatan, . D. & Kul, . O. (2025) Host–parasite interaction in latent cerebral toxoplasmosis: The role of cytokine response in a mouse model. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3558-3570. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.18 |