| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3505-3513 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(8): 3505-3513 Research Article Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouseOmar A. Al-Mahmood1*, Ayman M. Albanna2 and Israa M. Jweer31Department of Veterinary Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq 2College of Environmental Science, University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq 3Health Supervision Division, Nineveh Health Directorate, Ministry of Health and Environment, Mosul, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Omar A. Al-Mahmood. Department of Veterinary Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq. Email: omar.a.almoula [at] uomosul.edu.iq Submitted: 19/05/2025 Revised: 19/07/2025 Accepted: 27/07/2025 Published: 31/08/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

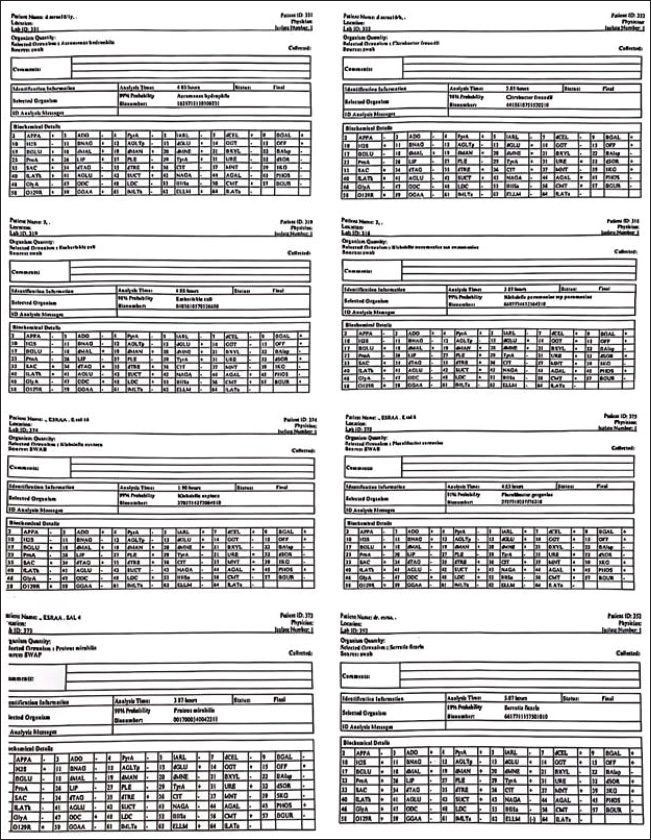

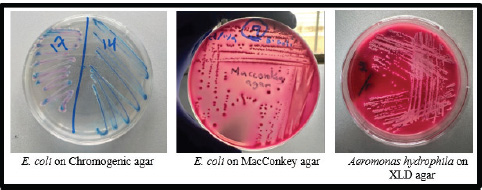

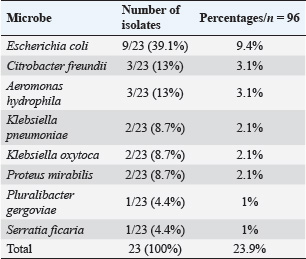

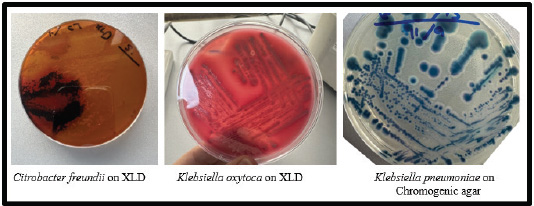

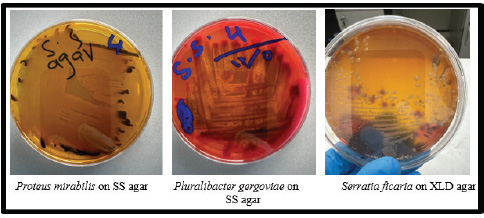

ABSTRACTBackground: The lack of modern slaughtering establishments and unsanitary practices can result in excessive microbial contamination of carcasses, posing health risks and causing economic losses. Aim: This study aimed to identify the numerous genera of bacteria that contaminated beef carcasses and estimate their percentages using a culture method and confirmation using the VITEK 2 methodology. Methods: This study included 96 swabs collected from beef carcasses after final wash at a slaughterhouse in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, between October and November 2023. All samples were grown on different media for 24 hours at 37°C to assess their phenotypic characteristics of colonies. Results: All samples contained aerobic bacteria (100%). Our data revealed several genera in beef carcasses. Of the 96 samples, 23 (23.9%) were positive for the beef microbiological profile (coliform bacilli and opportunistic pathogens). Seven genera were isolated and verified using the VITEK 2 Compact System. Escherichia coli had the most isolates (9.4%). Citrobacter freundii and Aeromonas hydrophila were the most common isolates (3 each) (3.1% respectively). Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Proteus mirabilis were isolated from beef carcasses at the rate of two isolates each (2.1%). Pluralibacter gergoviae and Serratia ficaria had one isolate in each of the beef carcass samples (1% and 1%, respectively). Conclusion: In our investigation, the quantity of bacteria in beef carcasses was generally acceptable, indicating commitment to the slaughterhouse’s food safety guidelines. Keywords: Opportunistic pathogens, Coliform bacilli, VITEK 2 system, Mosul abattoir. IntroductionThe tissues of a healthy animal (except the outer surface and digestive system) contain a small number of microbes, and the defense systems in the body of the living animal work efficiently against any microbial invasion, but the effectiveness of these systems disappears after slaughter (Nicholson, 2016). The cleanliness of the animal at slaughter depends on several factors, including the location of the farm, the method of slaughter, transportation to the slaughterhouse, food safety conditions and procedures available at the slaughterhouse, and skin contamination (FEHD, 2014). Foodborne pathogens represent common public health risks in both developed and developing countries, regardless of their economic status and geographic locations (Tegegne and Phyo, 2017). The public health burden from foodborne microbes is higher in developing countries (Odeyemi, 2016) due to poor food handling and sanitation practices, inadequate food safety laws, weak regulatory systems, lack of financial resources to invest in protective equipment, and lack of education and culture for slaughterhouse workers (Tegegne and Phyo, 2017). Foods intended for human consumption, especially foods of animal origin, are more hazardous unless food safety regulations are followed (Aluko et al., 2014). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2015) estimates that each year, 420,000 people die and 600 million become unwell because of eating contaminated food. These numbers demonstrate the urgent need for efficient microbial monitoring and control methods in the food supply system. Escherichia, Klebsiella, Serratia, and Citrobacter (known as coliform bacilli), as well as Proteus, are overt and opportunistic pathogens that cause various illnesses. Many species are part of the typical gut flora. Coliforms and Proteus are gram-negative bacilli. All genera except Klebsiella are flagellated. Certain strains create capsules. Virulence is frequently dependent on the presence of attachment pili (identified by certain hemagglutinating reactions). The three major groups of antigens used to define strains are H (flagellar), O (somatic), and K (capsular). (Forsythe et al., 2015). Pluralibacter gergoviae belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family and has been reported irregularly. While multidrug-resistant strains of P. gergoviae have been found, further genomic studies are needed to focus on antimicrobial resistance (Furlan and Stehling, 2023). Aeromonas hydrophila is a heterotrophic gram-negative bacterium. It can tolerate both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Aeromonas hydrophila was first isolated from humans and animals in the 1950s (Pessoa et al., 2022). Symptoms of foodborne disorders caused by bacteria or toxins can appear hours to days after consuming contaminated food. Foodborne illnesses arise when a self-established pathogen is present in the food and replicates itself in the consumer’s intestine (Guentzel, 1996). Although coliform bacilli are opportunistic, they can infect immunocompromised or immunocompetent patients after consuming contaminated food. For instance, Aeromonas, Pluralibacter, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Serratia, and Citrobacter species are considered potential human pathogens with gastrointestinal tract disorders as their primary clinical manifestations (Janda, 2006). Despite their widespread usage, traditional culturing and biochemical methods for microbial identification are frequently time-consuming and labor-intensive and may have several drawbacks, including low sensitivity, the requirement for specialized staff, and lengthy incubation times. These challenges can make it more difficult to identify microbes accurately and quickly, particularly when working with perishable foods like meat. The VITEK 2 Compact System has become a dependable and effective substitute for these drawbacks, offering precise microbiological identification in as little as 24 hours. This automated approach swiftly and accurately identifies a variety of bacterial species using sophisticated colorimetric technology and a large database (Ayeni et al., 2015; Al-Mahmood et al., 2021). Accordingly, this study was conducted to identify the different bacterial genera contaminating beef carcasses and to determine their prevalence. This was accomplished by combining traditional and modern methods for a more thorough microbial examination. Conventional culture techniques were first used, followed by confirmation and identification using the VITEK 2 system. High bacterial identification accuracy has been established using the VITEK 2 Compact System; identification rates for common bacteria have been reported to range from 93% to 99% (Funke et al., 1998). Materials and MethodsSample collection and handlingThe study included 96 swabs randomly collected from beef carcasses after final wash at a slaughterhouse in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, between October and November 2023. The swab test kit includes sterile sponge swabs, a Whirl-Pak® bag, gloves, and Butterfield’s Phosphate Buffer (World Bioproducts LLC, USA). Swabs were collected with 10 horizontal and 10 vertical movements. Subsequently, they were placed in a sample bag (Whirl-Pak® bag, USA) with 15 ml of phosphate buffer solution (USDA-FSIS, 2014) with a unique identification code. Microbiological analysisAll samples were grown on nutrient agar for 24 hours at 37°C to obtain qualitative bacterial counts. All media were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Swab samples were cultivated in tryptone soy broth and buffer peptone water for 24 hours at 37°C to enhance the growth of the bacteria. Then, 1 ml of cultured peptone water broth was mixed with 9 ml of selenite broth (enrichment medium) and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C for 24 hours. Then, a loop of selenite medium was obtained and grown on different media. Bacterial isolates were then cultivated on MacConkey agar, Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate agar (XLD agar), Salmonella Shigella agar (SS agar), and chromogenic agar (selective and differential media) for 24 hours at 37°C to assess their phenotypic characteristics. Identification using VITEK 2Subsequently, the VITEK 2 Compact System was used to confirm the identity of the bacterial isolates obtained from the initial culturing process. The VITEK 2 cards were loaded with bacterial suspensions and placed inside the device for automated analysis. The system performed biochemical profiling and compared the outcomes with its large database of microorganisms. Following a roughly 24-hour incubation time, the diagnostic results were produced and recorded automatically, offering a trustworthy identification of the bacterial species found in the samples. Ethical approvalThe Institutional Animal Care Committee of the College of Veterinary Medicine approved the research design on September 15, 2023, with reference number: UM.VET.2024.092. Statistical analysisDescriptive statistical analysis was performed to meaningfully summarize and arrange the gathered data. To illustrate the distribution of bacterial isolates, this involved computing frequencies and percentages. ResultsThere was a 100% contamination rate since aerobic bacteria were found in every sample of beef carcass that was examined. The results of our microbiological analysis showed that cattle carcasses have a varied bacterial community. The microbiological profile of beef includes opportunistic pathogens and bacterial species frequently linked to coliform bacilli, which were detected in 23 (23.9%) of the 96 analyzed samples. The VITEK 2 Compact System, an accurate automated platform for microbiological identification based on biochemical fingerprinting, was used to correctly identify the isolated bacteria (Fig. 1). Seven different genera of bacteria were isolated from the positive samples. The most frequently identified species was Escherichia coli, with nine recovered isolates (Fig. 2). The high prevalence of E. coli is not unexpected, as it is a common inhabitant of the intestinal tract of animals and an indicator of fecal contamination. Citrobacter freundii and A. hydrophila were among the most isolated species, with three isolates each (Table 1, Fig. 2). These bacteria are recognized as opportunistic pathogens and may cause illness in immuno-compromised individuals. Additional isolations included Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Proteus mirabilis, with two instances of each (Table 1, Figs. 3 and 4). These bacteria are usually found in the gut flora but can cause various infections if they enter sterile areas of the body. Lastly, two less commonly detected species—P. gergoviae and Serratia ficaria—were found in a single beef carcass sample (Table 1, Fig. 4). DiscussionPreviously, numerous microbes were innocuous commensals. They are now recognized as the cause of serious health concerns around the world. Most infections caused by this category of organisms are caused by a small number of species, including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Pluralibacter spp., Serratia spp., and P. mirabilis (Beck-Sague et al., 1994). The increased prevalence of coliforms, Proteus spp., and other Gram-negative organisms in diseases reflects not only a better understanding of their pathogenic potential but also the changing ecology of bacterial disease (Bergeron, 1995). Escherichia coli is commonly found in meat, and most pathogens responsible for foodborne illnesses have zoonotic origins (Sharma and Chattopadhyay, 2015). Escherichia coli had the highest number of isolates in our study compared to other microorganisms. Most major food safety failures resulting in consumer health issues and costly product withdrawals and recalls from the food supply chain of possibly contaminated meat products are related to microbiological risks, particularly pathogenic E. coli infections (Sofos, 2008; Al-Mahmood and Fraser, 2023; Al-Mahmood, 2023). Our results agreed with those of a previous study conducted in Mosul, where the prevalence of E. coli was higher in meat (41%) (Albanna et al., 2023; Othman et al., 2023), which emphasized poor food safety practices in slaughterhouses, cross-contamination during handling, and temperature abuse during storage (Warmate and Onarinde, 2023). Other studies have also reported a high prevalence of E. coli in meat (42% in the United States (Arthur et al., 2002; Al-Mahmood et al., 2021), 43% in India (Sethulekshmi et al., 2018), 54% in Egypt (Gwida et al., 2014), and 74% in South Africa (Vorster et al., 1994). Aeromonas spp. have been linked to food poisoning and certain illnesses in humans. Many investigations have attempted to link toxins such as cytotoxic enterotoxins to Aeromonas-related diseases (Sharma and Kumar, 2011). Furthermore, A. hydrophila is an important emerging foodborne pathogen due to its capacity to proliferate at low temperatures and adapt to harsh circumstances (Daskalov, 2006; Fernández-Bravo and Figueras, 2020). Our results showed modest levels of contamination with A. hydrophila compared with studies conducted in Iraq, where they recorded 42% isolates from beef (Yousif et al., 2023) and 14% from environmental sources (Abdulhasan et al., 2019). However, our study results align with those of those who isolated A. hydrophila from 3% of beef samples in Brazil (Rossi Júnior et al., 2006). Kumar et al. (2000) also detected A. hydrophila in 7% of beef samples in India. Regarding C. freundii, our findings showed low levels of contamination in the beef carcass samples, which suggested the need for cleaning and sanitation practices at the slaughterhouse. According to a study conducted in Iraq, it showed a similar percentage (4%) of contamination to our study (Awad and Al-Saadi, 2022). However, a study conducted in Basrah revealed a higher contamination of C. freundii (55%) (Al-Iedani et al., 2015). The reason for the increase may be attributable to the type of beef samples (ground beef) and butcher shop hygiene practices. Other countries (Tanzania and Egypt) revealed a high prevalence compared to our study (Medardus, 2017; Sallam et al., 2020), which may directly affect public health, causing food poisoning and urogenital infections (Mohamed et al., 2023). This indicated that animal excrement could be one of the potential sources of contamination in animal products across the food production chain. Klebsiella oxytoca is a significant bacterial isolate that causes hospital-acquired illnesses in humans and is resistant to several popular antibiotics (Singh et al., 2016). Sabota et al. (1998) identified K. pneumoniae as an enteroinvasive foodborne pathogen transmitted through burgers that induce gastroenteritis, which can result in acute multiorgan failure. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have been conducted to isolate Klebsiella spp. from meat samples. Klebsiella pneumoniae and K. oxytoca were recovered from beef carcasses, with two isolates each. This implies a low incidence of contamination, which might disclose the slaughterhouse’s hygienic conditions. In contrast to our study, Theocharidi et al. (2022) isolated Klebsiella spp. from beef samples with high prevalence (90%) (Theocharidi et al., 2022). In another study (China), Guo et al. (2016) reported the prevalence of K. pneumoniae in food samples with a contamination rate of 9.9%. According to a study conducted in the USA, the percentage of positive K. pneumoniae (fecal samples) was 80% from 100 cows (10 herds) in different states (Munoz et al., 2006). This means that the main source of carcass contamination is fecal contamination during slaughtering, particularly if not using proper hygienic practices. Hygienic skinning and evisceration techniques are required to reduce the risk of K. pneumoniae infection and other opportunistic bacteria Hartantyo et al. (2020).

Fig. 1. Rapid bacterial identification for different microbial genera achieved using the VITEK 2 system. This technique uses a succession of small biochemical assays inserted into specific cards to detect biochemical changes between bacteria.

Fig. 2. Culture characteristics of E. coli and A. hydrophila on different culture media. Escherichia coli colonies might be blue or purple depending on the chromogenic agar formulation. When E. coli ferments lactose, colonies turn pink to dark pink on MacConkey agar. Aeromonas hydrophila colonies appear colorless or pallid because they do not ferment lactose on MacConkey agar. Table 1. Prevalence of different microbial genera isolated from beef carcasses.

Fig. 3. Citrobacter freundii produced hydrogen sulfide H₂S, which led to the formation of black colonies on XLD agar. The cultivation characteristics of Klebsiella spp. vary between mediums (metallic blue-mucoid colonies on chromogenic agar).

Fig. 4. Proteus mirabilis (black colonies due to H₂S production), P. gergoviae (colonies are typically pinkish to colorless with a mucoid appearance), and S. ficaria (colorless colonies on XLD). The presence of P. mirabilis and other foodborne pathogens in beef samples illustrates how animal products serve as a significant reservoir for pathogenic organisms that cause disease. Maintaining cleanliness and hygiene is crucial to lowering the amount of harmful and opportunistic pathogens on raw meat (Gupta et al., 2014). Our findings showed lower contamination of P. mirabilis compared to previous studies in China (25%) (Ma et al., 2022) and Brazil (23%) (Sanches et al., 2021) conducted on beef. However, a local study in Iraq showed contamination with Proteus spp. at a rate of 8%, which agreed with our results (Al-Kubaisi and Al-Deri, 2022). Similar to our findings, another study carried out in Brazil found that P. mirabilis contamination was low, at 6% (Sanches et al., 2023). Effective food safety education and training for employees working in slaughter establishments help reduce the transmission of these pathogens to humans. Pluralibacter gergoviae (previously Enterobacter gergoviae) and S. ficaria are rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacteria that are motile and facultatively anaerobic (Brenner et al., 1980; Gul et al., 2011). Although a few studies have shown strong evidence of P. gergoviae directly contaminating beef meat, its close relation to the Enterobacteriaceae family suggests that P. gergoviae is also found in different meat products (Jain and Yadav, 2016). Our findings showed a low contamination rate (one isolate each of P. gergoviae and S. ficaria) in beef products, which is consistent with studies conducted in Egypt (El-Gendy et al., 2014; Nossair et al., 2014). Study limitationsThe lack of molecular confirmation techniques in this investigation may have reduced the microbial identification precision. The research was conducted using samples from one slaughterhouse, which may affect the generalizability of the findings to other locations. ConclusionThe inverse relationship exists between microbial diversity in beef carcasses and hygiene practices during slaughter. The number of bacteria was relatively acceptable in our study, indicating a commitment to implementing food safety practices in slaughterhouses. Overall, the results of this study highlighted that different genera of bacteria are present in beef carcasses; most of them are spoilage and opportunistic microorganisms. The main distinction between this study and earlier studies is that it examined the diversity of bacteria in beef samples. These findings are useful in knowing the level of contamination in the slaughtered animals and the severity of this contamination. This work contributes to this field by focusing not only on the presence of individual bacterial species but also on the broader microbial community structure on bovine carcasses. Understanding the microbial community composition provides valuable insights into the sources of contamination and the effectiveness of hygiene controls. Furthermore, the data forms a basis for monitoring slaughterhouse hygiene and guiding interventions aimed at reducing microbial risks. Further studies using molecular methods, such as next-generation sequencing, are recommended to identify the microbial diversity in beef carcass samples. Moreover, the study recommended establishing and rigorously enforcing hygienic procedures throughout the slaughtering process, including frequent staff training on proper sanitation, carcass handling, and equipment cleaning techniques to reduce microbial contamination during slaughter. AcknowledgmentWe would like to thank the slaughter facility that participated in this investigation. We sincerely appreciate their help. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. FundingThis study has not received any funds. Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed equally to this work. Data availabilityAll data were provided in the manuscript. ReferencesAbdulhasan, G.A., Alattar, N.S. and Jaddoa, N.T. 2019. Comparative study of some virulence factors and analysis of phylogenetic tree by 16S rDNA sequencing of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from clinical and environmental samples. Iraqi J. Sci. 60(11), 2390–2397. Albanna, A., Sedeeq, D. and Al Mahmood, O. 2023. Molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in profile bacteria isolated from water effluent in butcher shops of Mosul City. Migration Let. 20(S5), 599–607. Al-Iedani, A.A., Mustafa, J.Y. and Hadi, N.S. 2015. Comparison of techniques used in isolation and identification of Salmonella spp. and related genera from raw meat and abattoir environment of Basrah. Int. J. Sci. Tech. 143(3101), 1–7. Al-Kubaisi, M.S. and Al-Deri, A.H. 2022. Isolation of Proteus spp. bacterial pathogens from raw minced meat in Alkarkh area, Baghdad province. Int. J. Health Sci. 6(S4), 4196–4204; doi:10.53730/ijhs.v6nS4.9086 Al-Mahmood, O. 2023. Food safety and sanitation practices survey in very small halal and non-halal beef slaughterhouses in the United States. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 37(1), 1–7. Al-Mahmood, O., Bridges, W., Jiang, X. and Fraser, A. 2021. A longitudinal study: microbiological evaluation of two halal beef slaughterhouses in the United States. Food Control. 125, 107945; doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107945 Al-Mahmood, O.A. and Fraser, A.M. 2023. Molecular detection of Salmonella spp. and E. coli non-O157:H7 in two halal beef slaughterhouses in the United States. Foods 12, 347; doi:10.3390/foods12020347 Aluko, O., Ojeremi, T.T., Olaleke, D.A. and Ajidagba, E.B. 2014. Evaluation of food safety and sanitary practices among food vendors at car parks in Ile Ife, southwestern Nigeria. Food Control 11, 049; doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.11.049 Arthur, T.M., Barkocy-Gallagher, G.A., Rivera-Betancourt, M. and Koohmaraie, M. 2002. Prevalence and characterization of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli on carcasses in commercial beef cattle processing plants. Appl. Environ. Micro. 68(10), 4847–4852; doi:10.1128/AEM.68.10.4847-4852.2002 Awad, N. and Al-Saadi, M.J. 2022. Isolation and molecular diagnosis of Citrobacter freundii in raw meat (beef, mutton and fish) in Al-Rusafa district of Baghdad city. Int. J. Health Sci. 6(S8), 1482–1491. Ayeni, F.A., Gbarabon, T., Andersen, C. and Nørskov-Lauritsen, N. 2015. Comparison of identification and antimicrobial resistance pattern of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Amassoma, Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 15(4), 1282–1288. Beck-Sague, C., Villarino, E., Giuliano, D., Welbel, S., Latts, L., Manangan, L.M., Sinkowitz, R.L. and Jarvis, W.R. 1994. Infectious diseases and death among nursing home residents: results of surveillance in 13 nursing homes. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 15, 494. Bergeron, M.G. 1995. Treatment of pyelonephritis in adults. Med. Clin. North Am. 79, 619. Brenner, D.J., Richard, C., Steigerwalt, A.G., Asbury, M.A. and Mandel, M. 1980. Enterobacter gergoviae sp. nov.: a new species of Enterobacteriaceae found in clinical specimens and the environment. Int. J. Sys. Bacteriol. 30(1), 1–6; doi:10.1099/00207713-30-1-1 Daskalov, H. 2006. The importance of Aeromonas hydrophila in food safety. Food Control 17(6), 474–483. El-Gendy, N.M., Ibrahim, H.A., Al-Shabasy, N.A. and Samaha, A.A. 2014. Enterobacteriaceae in beef products (luncheon, pasterma, frankfurter, and minced meat) from Alexandria retail outlets. Alexa J. Vet. Sci. 41(1), 80–86; doi:10.5455/ajvs.151171 FEHD. 2014. Guide for microbiological specifications and standards in foods. Available via https://www.cfs.gov.hk/english/food_leg/files/food_leg_Microbiological_Guidelines_for_Food_e.pdf Fernández-Bravo, A. and Figueras, M.J. 2020. An update on the genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, epidemiology, and pathogenicity. Microorganisms 8(129), 3–6. Forsythe, S., Abbott, S. and Pitout, J. 2015. Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Cronobacter, Serratia, Plesiomonas, and other Enterobacteriaceae. In Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed. Eds., Jorgensen, J.H., Carroll, K.C., Funke, G., Pfaller, M.A., Landry, M.L., Richter, S.S. and Warnock, D.W. Washington, DC: ASM Press (American Society for Microbiology Press); doi:10.1128/9781555817381.ch38 Funke, G., Funke-Kissling, P. and Pfyffer, G.E. 1998. Evaluation of the VITEK 2 system for identification of medically relevant Gram-negative rods. J. Clin. Micro. 36(7), 1947–1952; doi:10.1128/JCM.36.7.1947-1952.1998 Furlan, J.P.R. and Stehling, E.G. 2023. Genomic insights into Pluralibacter gergoviae sheds light on emergence of a multidrug-resistant species circulating between clinical and environmental settings. Pathogens 12(11), 1335; doi:10.3390/pathogens12111335 Guentzel, M. 1996. Escherichia, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia, Citrobacter, and Proteus. In medical microbiology, 4th ed. Ed., Baron, S. Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Gul, M., Dogan, E., Kirecci, E., Ucmak, H., Dirican, E. and Karadag, A. 2011. Serratia ficaria isolated from sputum specimen. Acta. Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 58(3), 235–238; doi:10.1556/amicr.58.2011.3.7 Guo, Y., Zhou, H., Qin, L., Pang, Z., Qin, T., Ren, H., Pan, Z. and Zhou, J. 2016. Frequency, antimicrobial resistance and genetic diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae in food samples. PLoS One 11, e0153561; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153561 Gupta, R.K., Ali, S., Shoket, H. and Mishra, V.K. 2014. PCR-RFLP differentiation of multidrug resistant Proteus spp. strains from raw beef. Curr. Res. Micro. Biotech. 2(4), 426–430. Gwida, M., Hotzel, H., Geue, L. and Tomaso, H. 2014. Occurrence of Enterobacteriaceae in raw meat and in human samples from Egyptian retail sellers. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 565671; doi:10.1155/2014/565671 Hartantyo, S.H.P., Chau, M.L., Koh, T.H., Yap, M., Yi, T., Cao, D.Y.H., GutiÉrrez, R.A. and Ng, L.C. 2020. Foodborne Klebsiella pneumoniae: virulence potential, antibiotic resistance, and risks to food safety. J. Food Prot. 83(7), 1096–1103; doi:10.4315/JFP-19-520 Jain, A. and Yadav, R. 2016. Identification and characterization of pathogenic enterobacterial isolates responsible for egg contamination. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 15(6), 245–253. Janda, J.M. 2006. New members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (pp. 5–40). In The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria, 3rd ed. Eds., Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.H. and Stackebrandt, E. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. Kumar, A., Bachhil, V.N., Bhilegaonakar, K.N. and Agarwal, R.K. 2000. Occurrence of enterotoxigenic Aeromonas species in foods. J. Commun. Dis. 32(3), 169–174. Ma, W.-Q., Han, Y.-Y., Zhou, L., Peng, W.-Q., Mao, L.-Y., Yang, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, T.-J., Wang, H.-N. and Lei, C.-W. 2022. Contamination of Proteus mirabilis harboring various clinically important antimicrobial resistance genes in retail meat and aquatic products from food markets in China. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1086800; doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.1086800 Medardus, J.J. 2017. Citrobacter as a gastrointestinal pathogen, its prevalence and molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistant isolates in food-producing animals in Morogoro, Tanzania. Tanzania Vet. Assoc. Proceed. 35(Special Issue), 130–137. Mohamed, M., Kelany, M., Hammad, A., Ahmed, M. and Elsharouny, T. 2023. Controlling foodborne pathogenic Citrobacter freundii via lytic bacteriophages. SVU-Inter. J. Agri. Sci. 5(4), 121–129; doi:10.21608/svuijas.2023.251917.1323 Munoz, M.A., Ahlström, C., Rauch, B.J. and Zadoks, R.N. 2006. Fecal shedding of Klebsiella pneumoniae by dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 89(9), 3425–3430; doi:10.3168/jds. S0022-0302(06)72379-7 Nicholson, L. 2016. The immune system. Essays Biochem. 60(3), 275–301; doi:10.1042/EBC20160017 Nossair, M., Khaled, K., El Shabasy, N. and Samaha, I. 2014. Detection of some enteric pathogens in retailed meat. Alexa. J. Vet. Sci. 44, 67–73. Odeyemi, O.A. 2016. Public health implications of microbial food safety and foodborne diseases in developing countries. Food Nutr. Res. 60, 29819; doi:10.3402/fnr.v60.29819 Othman, S.H., Sheet, O.H. and Al-Sanjary, R. 2023. Phenotypic and genotypic characterizations of Escherichia coli isolated from veal meats and butchers’ shops in Mosul city, Iraq. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 37(1), 225–260; doi:10.33899/ijvs.2022.133819.2306 Pessoa, R.B.G., Oliveira, W.F., Correia, M.T.S., Fontes, A. and Coelho, L.C.B.B. 2022. Aeromonas and human health disorders: clinical approaches. Front. Micro. 13, 868890; doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.868890 Rossi Júnior, O.D., Amaral, L.A., Nader Filho, A. and Schocken-Iturrino, R.P. 2006. Bacteria of the genus Aeromonas in different locations throughout the process line of beef slaughtering. Rev. Port. Ciênc. Vet.. 101(557–558), 125–129. Sabota, J.M., Hoppes, W.L., Ziegler, J.R., DuPont, H., Mathewson, J. and Rutecki, G.W. 1998. A new variant of food poisoning: enteroinvasive Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli sepsis from a contaminated hamburger. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 93(1), 118–119; doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.118_c.x Sallam, K.I., Abd-Elghany, S.M., Hussein, M.A., Imre, K., Morar, A., Morshdy, A.E. and Sayed-Ahmed, M.Z. 2020. Microbial decontamination of beef carcass surfaces by lactic acid, acetic acid, and trisodium phosphate sprays. BioMed Res. Int. 12, 2324358; doi:10.1155/2020/2324358 Sanches, M.S., Rodrigues da Silva, C., Silva, L.C., Montini, V.H., Lopes Barboza, M.G., Migliorini Guidone, G.H., Dias de Oliva, B.H., Nishio, E.K., Faccin Galhardi, L.C., Vespero, E.C., Lelles Nogueira, M.C. and Dejato Rocha, S.P. 2021. Proteus mirabilis from community-acquired urinary tract infections (UTI-CA) shares genetic similarity and virulence factors with isolates from chicken, beef and pork meat. Microb. Pathog. 158, 105098; doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105098 Sanches, M.S., Silva, L.C., Silva, C.R.D., Montini, V.H., Oliva, B.H.D.D., Guidone, G.H.M., Nogueira, M.C.L., Menck-Costa, M.F., Kobayashi, R.K.T., Vespero, E.C. and Rocha, S.P.D. 2023. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and clonal relationship in ESBL/AmpC-producing Proteus mirabilis isolated from meat products and community-acquired urinary tract infection (UTI-CA) in Southern Brazil. Antibiotics (Basel) 12(2), 370; doi:10.3390/antibiotics12020370 Sethulekshmi, C., Latha, C. and Anu, C.J. 2018. Occurrence and quantification of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from food matrices. Vet. World. 11(2), 104–111; doi:10.14202/vetworld.2018.104-111 Sharma, K.P. and Chattopadhyay, U.K. 2015. Assessment of microbial load of raw meat samples sold in the open markets of the city of Kolkata. IOSR J. Agri. Vet. Sci. 8(3), 24–27. Sharma, I. and Kumar, A. 2011. Occurrence of enterotoxigenic Aeromonas species in foods of animal origin in Northeast India. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 15, 883–887. Singh, L., Cariappa, M.P. and Kaur, M. 2016. Klebsiella oxytoca: an emerging pathogen? Med. J. Armed Forces India 72(Suppl 1), S59–S61; doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.05.002 Sofos, J.N. 2008. Challenges to meat safety in the 21st century. Meat. Sci. 78(1–2), 3–13. Tegegne, H.A. and Phyo, H.W. 2017. Food safety knowledge, attitude and practices of meat handlers in abattoir and retail meat shops of Jigjiga Town, Ethiopia. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 58, E320–E327; doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2017.58.4.737 Theocharidi, N.A., Balta, I., Houhoula, D., Tsantes, A.G., Lalliotis, G.P., Polydera, A.C., Stamatis, H. and Halvatsiotis, P. 2022. High prevalence of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greek meat products: detection of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes by molecular techniques. Foods 11(5), 708; doi:10.3390/foods11050708 USDA-FSIS. 2014. National beef and veal carcass microbiological baseline data collection program actual study. Available via http://www.senasa.gov.ar/sites/default/files/ARBOL_SENASA/ANIMAL/ABEJAS/INDUSTRIA/ESTABL_IND/REGISTROS/usa_attachment-for44-15.pdf Vorster, S.M., Greebe, R.P. and Nortje, G.L. 1994. Incidence of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in ground beef, broilers and processed meats in Pretoria, South Africa. J. Food Prot. 57(4), 305–310; doi:10.4315/0362-028X-57.4.305 Warmate, D. and Onarinde, B.A. 2023. Food safety incidents in the red meat industry: a review of foodborne disease outbreaks linked to the consumption of red meat and its products, 1991 to 2021. Int. J. Food Micro. 398, 110240; doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2023.11024 World Health Organization (WHO). 2015. Estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press (Official publishing division of the World Health Organization). Available via https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565165 Yousif, S.A., JakhsI, N.S. and Jwher, D.M. 2023. Association between antimicrobial resistance and biofilm production of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from beef and mutton in Duhok abattoir. Egypt. J. Vet. Sci. 54(3), 479–490. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Al-mahmood OA, Albanna AM, Jweer IM. Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 Web Style Al-mahmood OA, Albanna AM, Jweer IM. Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=259361 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Al-mahmood OA, Albanna AM, Jweer IM. Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Al-mahmood OA, Albanna AM, Jweer IM. Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(8): 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 Harvard Style Al-mahmood, O. A., Albanna, . A. M. & Jweer, . I. M. (2025) Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. Open Vet. J., 15 (8), 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 Turabian Style Al-mahmood, Omar A., Ayman M. Albanna, and Israa M. Jweer. 2025. Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 Chicago Style Al-mahmood, Omar A., Ayman M. Albanna, and Israa M. Jweer. "Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Al-mahmood, Omar A., Ayman M. Albanna, and Israa M. Jweer. "Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse." Open Veterinary Journal 15.8 (2025), 3505-3513. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Al-mahmood, O. A., Albanna, . A. M. & Jweer, . I. M. (2025) Isolation of some microbial genera from beef carcasses in Mosul slaughterhouse. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3505-3513. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.13 |