| Review Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(10): 4814-4833 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(10): 4814-4833 Review Article Cryptosporidiosis: A global threat to human and animal healthWimbuh Tri Widodo1*, Aswin Rafif Khairullah2, Bima Putra Pratama3, Rahmania Ambarika4, Abdul Hadi Furqoni5,6, Sonny Kristianto1, Bantari Wisynu Kusuma Wardhani7,8, Widoretno Widoretno5, Khariri Khariri5, Luluk Hermawati9, Auliyani Andam Suri10, Ikechukwu Benjamin Moses11, Alifiani Kartika Putri12, Dea Anita Ariani Kurniasih13, Masri Sembiring Maha5, Andi Thafida Khalisa8, Riza Zainuddin Ahmad2 and Syahputra Wibowo141Master of Forensic Science, Postgraduate School, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 2Research Center for Veterinary Science, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia 3Research Center for Agroindustry, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), South Tangerang, Indonesia 4Universitas Strada Indonesia, Kediri, Indonesia 5Center for Biomedical Research, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, West Java, Indonesia 6Research Center on Global Emerging and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases, Institute of Tropical Disease, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 7Research Center for Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Traditional Medicine, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia 8Faculty of Military Pharmacy, Universitas Pertahanan, Bogor, Indonesia 9Department of Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Banten, Indonesia 10Departement of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, Banten, Indonesia 11Department of Applied Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria 12Muhammadiyah Hospital Tuban, Tuban, Indonesia 13Research Center for Public Health and Nutrition, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia 14Eijkman Research Center for Molecular Biology, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Wimbuh Tri Widodo. Postgraduate School of Forensic Science, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. Email: wimbuh.tri [at] pasca.unair.ac.id Submitted: 25/05/2025 Revised: 30/08/2025 Accepted: 10/09/2025 Published: 31/10/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

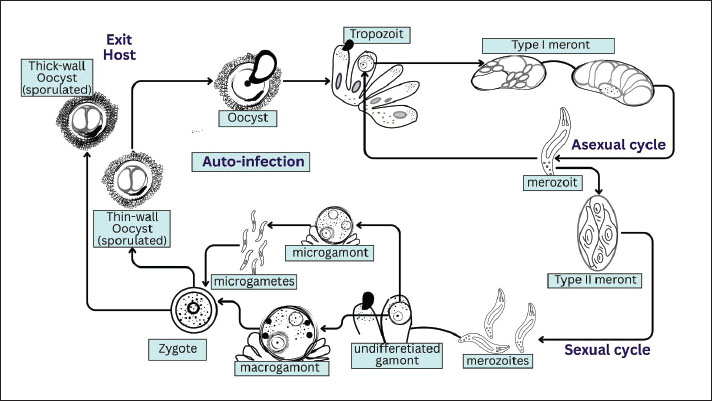

AbstractCryptosporidiosis is a significant zoonotic illness that infects both humans and animals. The protozoan parasite that causes this illness is a member of the genus Cryptosporidium, a eukaryote in the phylum Apicomplexa. The parasite Cryptosporidium is monoxenic, meaning it has only one host. Oocyte-to-oocyte development occurs in the host organism without an intermediate host. Developing nations have a far greater prevalence of Cryptosporidium infections because many people there still lack access to basic sanitation and clean water. Both innate and adaptive immune system components are involved in the host immunological response to Cryptosporidium infection; both pathways contribute to the defense against Cryptosporidiosis. Globally, cryptosporidiosis is estimated to cause tens of millions of cases each year, with a prevalence of 10%–20% among children under five in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, whereas approximately 750,000 cases occur annually in the United States. The disease is more common in developing countries due to limited access to safe water and sanitation. Cryptosporidium can be detected in the digestive tract, lungs, and conjunctiva; however, the intestines are most susceptible to cryptosporidiosis. Nowadays, most people agree that Cryptosporidium is a frequent parasite that causes diarrheal illness. Furthermore, infections caused by Cryptosporidium have spread to humans, primarily affecting individuals with immunological problems, such as those with AIDS. Cryptosporidiosis is typically diagnosed by looking for parasite eggs, oocyte antigen, or oocyte DNA in stool samples. Consuming food or beverages containing the oocysts of these protozoa can infect both humans and animals. Most diseased individuals and animals with robust immune systems can heal themselves without medical intervention. The main strategy for preventing cryptosporidiosis is to reduce or eradicate environmental contamination with infectious oocysts, as there is currently no effective treatment for the disease. Keywords: Cryptosporidiosis, Diarrhea, Immunity, Oocyst, Parasite, Prevention. IntroductionCryptosporidiosis is a significant zoonotic disease that affects the intestinal tract of both humans and animals (Gerace et al., 2019; Alarcón-Zapata et al., 2023). It is caused by Cryptosporidium, a protozoan parasite belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa (Bouzid et al., 2013). All Cryptosporidium species are obligate intracellular parasites that depend on host cells to complete their life cycle (Arrowood, 2002). The parasite undergoes three major developmental phases—schizogony, gametogony (sexual reproduction), and merogony (asexual reproduction)—followed by sporogony (sporulation) (Dragomirova, 2022). An encysted oocyst stage is excreted in the feces of the host, allowing transmission to new hosts (Leitch and He, 2012). Cryptosporidium is a small protozoan, measuring 4–6 µm, and typically inhabits the microvilli of the mucosal epithelium in many vertebrates, including humans (Xiao et al., 2004a). Tyzzer first described and named Cryptosporidium in 1907 (Tzipori and Widmer, 2008). However, its pathogenic role was not recognized until 1955, when it was associated with gastrointestinal disease in turkeys (Leitch and He, 2012). In the early 1980s, Cryptosporidium was identified as a major cause of diarrheal illness in ruminants (O'Hara and Chen, 2011) and later became established as an important human pathogen, especially among individuals with immunodeficiency, such as those with AIDS (Hunter and Nichols, 2002). Today, Cryptosporidium is widely acknowledged as a common cause of acute diarrhea in healthy individuals and a severe, sometimes life-threatening infection in young children and immunocompromised patients (Prabakaran et al., 2023). Transmission occurs mainly through the ingestion of food or water contaminated with infectious oocysts (Pumipuntu and Piratae, 2018). Prevalence is particularly high in developing countries, where sanitation and clean water access remain limited (Mahmoudi et al., 2017). Oocysts are resistant to many disinfectants, including chlorine, enabling their persistence in drinking water, swimming pools, and recreational facilities (Ali et al., 2024a). Human-to-human transmission has been reported in hospitals, households, day-care centers, and through sexual contact (Ramirez et al., 2004). Zoonotic transmission is also well documented, involving livestock, pets, wild animals, and veterinary workers (El-Alfy and Nishikawa, 2020). In livestock, cryptosporidiosis causes economic losses by increasing veterinary costs, reducing growth, and contributing to mortality (Santin, 2020). Pets and wild animals may also serve as reservoir hosts, further increasing the human infection risk (Pal et al., 2021). Globally, the disease remains a serious health concern, ranking second only to rotavirus as the leading cause of diarrhea and mortality in children (Mafokwane et al., 2023). Currently, there is no effective cure for cryptosporidiosis. Cryptosporidiosis is a global issue with serious implications for food safety, veterinary medicine, and public health, given its impact on both human and animal health (LeJeune and Kersting, 2010). This article reviews the key aspects of cryptosporidiosis, including its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, and current treatment and prevention approaches. It also highlights existing knowledge gaps and future research needs to support better control and management of this important disease. EtiologyCryptosporidium oocysts are among the smallest within coccidia, typically ovoid to spherical, and fully sporulated. Their size averages about 4.5 μm in C. parvum and 5.6 μm in C. muris (Helmy and Hafez, 2022; Shehata et al., 2024). Each sporulated oocyst contains four sporozoites and a residuum composed of small granules and a membrane-bound globule (O'Hara and Chen, 2011). Cryptosporidium lacks morphological traits, such as polar granules and micropyles, which are commonly present in coccidian oocysts (Bruno et al., 2006). The oocyst wall is smooth, colorless, and approximately 50 nm thick, consisting of two electron-dense layers separated by a thin electron-lucent gap (Nageeb et al., 2024). A faint suture line may sometimes be observed at one pole of the oocyst under light microscopy (Ruecker et al., 2007). Cryptosporidium belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa, class Sporozoa, subclass Coccidia, order Eucoccidiorida, and family Cryptosporidiidae (Mamedova and Karanis, 2025). Historically, species differentiation has been based on host specificity, endogenous site location, and morphological features (Gerace et al., 2019). However, oocyst morphology alone is unreliable for species identification because many species have overlapping size ranges, leading to misclassification (Tosini et al., 2010). Early taxonomic attempts often relied on the host origin. For example, C. agni was described from sheep (Barker and Carbonell, 1974), and C. garnhami or C. enteritis from humans (Wilmsmeyer et al., 1993). Nevertheless, these species names are not considered valid due to the absence of sufficient molecular, biological, and morphological data to distinguish them from recognized species (Bones et al., 2019). Recent findings also show that many Cryptosporidium species can infect multiple hosts, and some researchers suggest a broader species concept (Rideout et al., 2024). The morphological differentiation of oocysts is only reliable at extreme sizes. Cryptosporidium muris with large oocysts typically infects the gastric mucosa of mammals, whereas C. parvum with small oocysts infects the intestinal mucosa (Abeywardena et al., 2015). Cryptosporidium has been reported in several vertebrates, including birds, fish, reptiles, and mammals. Valid recognized species include C. andersoni, C. parvum, C. hominis, C. galli, C. baileyi, C. meleagridis, C. molnari, C. canis, C. muris, C. felis, C. saprophilum, and C. wrairi (Alves et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2007; García-Livia et al., 2020; Scorza et al., 2022). Life cycleCryptosporidium is monoxenous (its direct life cycle is completed within a single host). After ingestion or inhalation of sporulated oocysts, excystation releases four sporozoites (~5 μm) that invade epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract—and occasionally the respiratory tract—at the brush border within an intracellular but extracytoplasmic niche. Endogenous development proceeds through three major phases: merogony (asexual replication, also termed schizogony), gametogony (differentiation into microgamonts and macrogamonts), and sporogony (zygote formation and in-host sporulation) (Hijjawi, 2004; Heo et al., 2018; Tandel et al., 2019 ; English et al., 2022). Two types of oocysts are produced: thin-walled oocysts that enable autoinfection and thick-walled oocysts that are immediately infectious upon excretion and mediate fecal–oral transmission (Helmy and Hafez, 2022; Hussain et al., 2025). Exogenous development involves the persistence of thick-walled, fully sporulated oocysts shed in the feces of infected hosts (Leitch and He, 2012). Oocysts are excised following ingestion or inhalation, releasing motile sporozoites that invade epithelial cells (Vanathy et al., 2017). Within the host cell, Cryptosporidium resides in a parasitophorous vacuole located just beneath the apical membrane; this compartment is intracellular yet outside the host cytoplasm, bounded by a host-derived membrane and a parasite-derived interface (including a feeder organelle) (Xu et al., 2024). Oocyst shedding typically lasts 7–30 days, depending on host immunity, and thin-walled oocysts drive endogenous reinvasion (autoinfection) (Leitch and He, 2012; Balendran et al., 2024). The host stage of the biological life cycle of Cryptosporidium spp. is illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Host stage of the biological life cycle of Cryptosporidium spp. It involves two developmental phases: intracellular asexual and sexual reproduction through Type I and Type II meront, which produce gamont and zygotes. Environmental transmission occurs when zygotes develop into thick-walled oocysts, and auto-infection is possible through the production of thin-walled oocysts, which preserves the parasite and supports its spread to animals and humans. At the genomic and metabolic levels, Cryptosporidium has a compact genome (~9.2 Mb across eight chromosomes) and shows reductions in several organelles and core metabolic pathways typical of Apicomplexa and other eukaryotes (Widmer and Sullivan, 2012; Ryan and Hijjawi, 2015). Consequently, due to the loss of key pathways (e.g., oxidative phosphorylation and many biosyntheses), Cryptosporidium species depend extensively on the host for nutrients; energy generation relies mainly on glycolysis and substrate-level phosphorylation. This dependency is reflected in an expanded repertoire of transporters for nutrient acquisition (Xu et al., 2004; Mazurie et al., 2013; Li et al., 2021b). HistoryIn 1895, Clarke (1895) reported spores of what he termed “free-encapsulated coccidia” in the cardiac glands of rat stomachs. Experimental mice that ingested these spores became ill within a week. Later, the prominent American parasitologist Edward Ernest Tyzzer studied similar organisms and, in 1910–1912, described them as C. muris, which infected the gastric epithelium of several strains of laboratory mice (Tyzzer, 1910; Tyzzer, 1912). Tyzzer also described a second species, C. parvum, inhabiting the small intestine of rats. Unlike typical coccidia, Cryptosporidium oocysts lack sporocysts surrounding the sporozoites, which is reflected in the genus name (Tzipori and Widmer, 2008; Pumipuntu and Piratae, 2018). Although the life cycle stages of Cryptosporidium were only faintly visible under light microscopy, Tyzzer (1907) was able to identify and order them, noting that the oocyst sporulates while still attached to the host cell, enabling autoinfection (Tyzzer, 1907). He concluded that the parasite obtains nutrients from the host via a specialized attachment organelle, later termed the feeder organelle. In 1986, Current et al. (1986) expanded Tyzzer’s work using electron microscopy, which confirmed schizogony with multiple generations and established the now widely accepted model of the life cycle. Electron microscopy and freeze-fracture techniques further demonstrated the intracellular but extracytoplasmic localization of Cryptosporidium (Tzipori and Widmer, 2008). Between 1961 and 1986, morphological studies led to the identification of nearly 20 additional Cryptosporidium species from fish, birds, mammals, and reptiles (Robinson et al., 2010). However, only a limited number, such as C. muris and C. parvum, are now considered valid, as many earlier names lacked sufficient molecular and biological support. Slavin (1955) was the first to link C. meleagridis infection to clinical disease when he reported acute diarrhea and mortality in young turkeys, later attributed to C. meleagridis. In 1971, C. parvum was recognized as a cause of diarrhea in calves, raising its veterinary importance (Roblin et al., 2023). C. parvum is a major cause of neonatal diarrhea in ruminants (Resnhaleksmana et al., 2021; Sawant et al., 2021; Sheoran et al., 2022; Veshkini et al., 2024). Additional species of clinical significance were later identified, including C. baileyi, a cause of respiratory disease in poultry (Zaheer et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022). The first human case of Cryptosporidium infection was reported in 1976. C. parvum and C. hominis have been established as important human pathogens, causing acute self-limiting diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals and severe, chronic disease in immunocompromised patients, especially those with AIDS (Rossle and Latif, 2013). EpidemiologyAlthough the global incidence of cryptosporidiosis is estimated to be approximately three cases per 100,000 population, the true prevalence is likely much higher—up to 100 times greater—because many cases are underreported or misdiagnosed due to non-specific clinical symptoms and limited diagnostic capacity (Gerace et al., 2019). The burden is disproportionately higher in developing countries, where the lack of access to safe water and adequate sanitation promotes widespread transmission (Ahmed and Karanis, 2020). Cryptosporidiosis is a major cause of childhood morbidity in these settings. Accounting for 10%–15% of severe diarrheal episodes in undernourished children aged 5 years (Helmy and Hafez, 2022). Outbreaks linked to contaminated drinking water, recreational water, and swimming pools have been documented in many countries, highlighting the resilience and global distribution of the parasite (Mahmoudi et al., 2017; Ali et al., 2024b). Although more than 30 Cryptosporidium species have been described, only a few are commonly associated with human infection, notably C. hominis, C. parvum, C. meleagridis, C. felis, and C. canis (Šlapeta, 2013; Ryan et al., 2014; Ayinmode et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2024). C. hominis is considered anthroponotic, infecting only humans, whereas C. parvum is primarily zoonotic, circulating between humans and ruminants. Consequently, C. parvum infections are frequently linked to livestock contact and animal husbandry practices (Hunter and Thompson, 2005; Dixon et al., 2011; Ehsan et al., 2015). Zoonotic transmission from less common hosts has also been reported, although it is relatively rare. Sporadic human cases have been associated with exposure to sheep (Dessì et al., 2020), horses (Li et al., 2019), goats (Yang et al., 2021), and rats (Suprihati et al., 2024). Other species adapted to companion animals, such as C. canis in dogs and C. felis in cats, occasionally infect humans, usually immunocompromised individuals, although transmission from household pets to humans remains infrequent (Scorza et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Dărăbuș et al., 2025). This epidemiological pattern highlights the dual importance of anthroponotic species (such as C. hominis) and zoonotic species (such as C. parvum) in sustaining human-to-human transmission and bridging infections between animals and humans, respectively. Together, these factors contribute to the widespread and persistent burden of cryptosporidiosis across diverse settings. At the global level, the World Health Organization estimates that tens of millions of cryptosporidiosis cases occur annually, with the highest burdens reported in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where infection rates in children under five can reach 10%–20% (Kotloff et al., 2013; Khalil et al., 2018) . In the United States, approximately 7,500 laboratory-confirmed cases are reported each year, although the true number is believed to exceed 750,000 due to underdiagnosis (CDC, 2023) . In Europe, surveillance data indicate more than 14,000 cases annually, with the United Kingdom, Germany, and Ireland being the most affected countries (EFSA, 2022) . Such regional disparities underscore the global significance of cryptosporidiosis as a public health and veterinary concern. PathogenesisThe pathogenic mechanisms that cause Cryptosporidium to cause diarrhea, malabsorption, and wasting are still not well understood. The first host-parasite interaction of invasion and attachment is a crucial step in pathogenesis, regardless of the method used. Numerous elements impacting attachment and the ultrastructural features of invasion and attachment have been described. However, the precise host and parasite chemicals involved in this process are poorly understood (Smith et al., 2005). It is crucial to understand these compounds to understand the harmful mechanisms that this parasite employs. Many parasite ligands and host receptors are involved in the first host-parasitic interaction, which takes the form of attachment, invasion, and the creation of the parasitophorous vacuole (O’Hara and Chen, 2011). This interaction has been thoroughly investigated in Apicomplexans, including Plasmodium, Eimeria, and Toxoplasma (Janouškovec et al., 2019). The apical complex, which consists of specialized secretory organelles such as micronemes, dense granules, and rhoptry, is present in the invasive “zoite” stage of the Apicomplexa (Gubbels and Duraisingh, 2012). These organelles release proteins that aid in adhesion, invasion, and the development of the parasitophorous vacuole during the first host-parasite interaction (Bouzid et al., 2013). Some micronemal proteins express distinct domains, whereas others have sticky “modules” that are conserved throughout Apicomplexan parasites (Sanderson et al., 2008). The discovery of surface and/or apical complex proteins [including circumsporozoite-like (CSL), GP900, p23/27, TRAP C1, GP15, CP 15, CP60/15, cp47, gp40/45, and gp15/Cp17] that share characteristics with other Apicomplexans and mediate these interactions is a result of the growing recognition of Cryptosporidium as an emerging human pathogen (Tzipori and Widmer, 2008). A large number of these proteins have already been reviewed (Theodos, 1998; Tomley and Soldati, 2001). Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against repetitive carbohydrate epitopes are used to identify the CSL antigen, a highly glycosylated 1,300 kDa glycoprotein (Riggs, 2002). This mAb causes a reaction similar to that of a circumsporozoite, where the antigen is moved posteriorly along the sporozoite pellicle, causing the infection to stop spreading. In vitro and in vivo, this antibody neutralizes infection in a mouse model of cryptosporidiosis (Riggs et al., 1997). CSL is found on the surface of sporozoites and merozoites as well as in the micronema and dense granules of the apical complex (Langer and Riggs, 1999). The purified protein exhibits saturable and dose-dependent binding to host cells (Paluszynski et al., 2014). According to a recent study, CSL attaches to the 85-kDa receptor of intestinal epithelial cells (Langer et al., 2001). Although the molecular structure of this protein is unknown, these results collectively suggest that CSL is a ligand driving adhesion and invasion. Similar to CSL, the apical microneme complex synthesizes GP900, a highly glycosylated high molecular weight glycoprotein that is secreted onto the surface of the invasive zoite stage and released in trail form during gliding movement (Wanyiri and Ward, 2006). According to an analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence of the gene, the gene encoding GP900 is a multidomain protein with a transmembrane domain, a cytoplasmic tail, and cysteine-rich and mucin-like domains (Bhalchandra et al., 2013). Both O-linked and N-linked glycosylation are widely present in GP900 (Rider and Zhu, 2010). Purified natural GP900, the recombinant protein’s cysteine-rich domain, and antibodies to this domain bind to intestinal epithelial cells and competitively inhibit C. parvum infection in vitro (Cevallos et al., 2000a). Our findings imply that GP900 mediates invasion and attachment as well. Whether the GP900 and CSL are related in any way remains unknown. Micronemal proteins, such as TRAP, CTRP, CS, Etp100, and MIC-2 from the Apicomplexans linked to Plasmodium falciparum, Eimeria tenella, and Toxoplasma gondii, respectively, are homologous to the thrombospondin-related adhesive protein of Cryptosporidium-1 (TRAP C1) (Boucher and Bosch, 2015). These proteins mediate attachment to host cells and feature a conserved thrombospondin domain that is distinguished by the presence of multiple TRMs. The deduced amino acid sequence of TRAP C1 includes an N-terminal signal sequence, a polyserenin domain, a thrombospondin domain with six TRMs, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail (Bhalchandra et al., 2013). Although TRAP C1 is localized to the apical region of sporozoites by antibodies to recombinant TRAP C1, there is no experimental proof that TRAP C1 plays a role in invasion or attachment. Another mucin-like O-glycosylated glycoprotein, gp40, has recently been identified. It is secreted from the parasite surface and is found on the surface and apical region of C. parvum’s invasive stages (Dąbrowska et al., 2023). Native C. parvum gp40 binds selectively to host cells, suggesting that the protein is involved in adhesion and invasion, and gp40-specific antibodies block infection in vitro. The gp40-coding gene, Cpgp40/15, has been cloned and sequenced (Cevallos et al., 2000b). A polyserine domain with many anticipated mucin-type O-glycosylation sites, an N-terminal signal peptide, and a hydrophobic region at the C-terminal end that is compatible with that needed for glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor addition were all found in the inferred amino acid sequence of this gene (Tran and Hagen, 2013). Cpgp40/15 not only encodes gp40 but also a 15/17-kDa immunodominant glycoprotein that is present on the invasive stage’s surface and participates in host-parasite interactions (Preidis et al., 2007). Gp40 and gp15 are generated by post-translational processing of precursor glycoproteins that are expressed in the parasite’s internal stages and encoded by Cpgp40/15 (Wanyiri et al., 2007). The C-terminal part of the gp40/15 precursor, gp15, and the soluble N-terminal segment, gp40, appear to remain connected following PTP. Thus, gp15, which is attached to the parasite surface by GPI linkage, may serve as a “stalk” to attach gp40 (Winter et al., 2000). The Cpgp40/15 gene has an unparalleled degree of polymorphism, which is significantly higher than that of any other gene that has been examined in Cryptosporidium to date (Leav et al., 2002). The length of the N-terminal polyserine domain was the primary source of variance in genotype 2 isolates. Nonetheless, at least four allelic subgroups in genotype 1 isolates are defined by a large number of single-nucleotide and single-amino acid polymorphisms (Priest et al., 2001). The discovery of widespread polymorphism in the Cpgp40/15 locus indirectly supports the role of this glycoprotein in facilitating infection, which is consistent with its gene product being a surface-associated virulence determinant that may be under host immunological pressure (Widmer and Lee, 2010). Both isolate genotypes have a single copy of the Cpgp40/15 gene, which is expressed as numerous transcripts produced by alternate polyadenylation (O’Connor et al., 2002). The predicted signal sequence, GPI anchor attachment site, proteolytic processing site, predicted O-glycosylation site in the polyserine domain, and 3′ UTR are conserved among isolates despite the broad polymorphism in the Cpgp40/15 coding sequence, indicating that these regions play a significant role in structure and function (Cevallos et al., 2000b). Cp 47 is a membrane-associated protein that binds to the surface of intestinal epithelial cells and is localized to the apical region of sporozoites (Nesterenko et al., 1999). However, no clone of the gene encoding this protein has been made. According to experimental or indirect data, the proteins mentioned above appear to play a role in facilitating adhesion and invasion. However, the inability to grow C. parvum in vitro and the lack of appropriate transient or stable DNA transfection systems, such as those created for other Apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma, have significantly impeded efforts to definitively determine the functional role of this protein (Nesterenko et al., 1999). Immune responseInnate and adaptive immune system components are involved in the host immunological response to Cryptosporidium infection; both processes contribute to the defense against Cryptosporidiosis. The initial line of defense is intestinal epithelial cells, followed by the recruitment of innate immune cells, such as mast cells, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and macrophages (Ludington and Ward, 2015). The primary basis for diagnosis is the detection of oocysts from fecal material, and cell-mediated immunity is a crucial component of the immunological response to infection (Chalmers and Katzer, 2013). Intestinal epithelial cells are a crucial part of gastrointestinal mucosal defense to protect the intestinal mucosa from commensal microbes and pathogenic organism invasion (He et al., 2021). Furthermore, because Cryptosporidium produces parasitophorous vacuoles in infected host cells and releases antimicrobial peptides, these cells are crucial for the start, control, and resolution of innate and adaptive immune responses to Cryptosporidium infection (Stoyanova and Pavlov, 2019). Additionally, chemokines and inflammatory cytokines stimulate immune effector cells to the infection site, and nitric oxide can kill and stop C. parvum from growing (He et al., 2021). Immunoevasion mechanism of cryptosporidiosis in infected epithelial cells through NF-κB signaling activation to initiate antiapoptotic cell death signals in infected cells (Hussain et al., 2025). IFN-γ-dependent gene transactivation in the intestinal epithelium may be suppressed as a result of the decrease of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1α (STAT1α), a crucial transcription factor in IFN-γ signaling (Nava et al., 2010). The expression of the antiparasitic cytokine C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20) is suppressed when host epithelial cells are infected (Li et al., 2024). CD3+/CD4+ cells are essential for the recovery of the immune system from cryptosporidiosis (Korbel et al., 2011). CD4+ T cells are crucial after antigen stimulation because they secrete cytokines, including IL-2, IFN-α, and IFN-γ from Th1 cells and IL-4 and IL-6 from Th2 cells. The IFN-γ also prevents Cryptosporidium disease invasion (Borad and Ward, 2010). Sporozoites cause dendritic cells and macrophages to release IL-12 during the infection’s acute phase. IL-12, in turn, combines with TNF-α and IL-18 to activate NK cells (Mead, 2023). Furthermore, certain immunocompetent cells generate proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6) that have protective effects, and TNF-α stops Cryptosporidium infection in enterocytes (Cohn et al., 2022). This implies that host immunological factors play a significant role in the regulation of cryptosporidiosis. PathologyCryptosporidiosis can be detected in the digestive tract, lungs, and conjunctiva; however, the intestines sustain most of the damage from cryptosporidiosis (Pardy et al., 2024). Swelling of the mesenteric lymph nodes occurs rarely (Perez-Cordon et al., 2014). The pathophysiology of this disease may involve the toxic effects and sensitization of the parasite through its metabolic products and toxins in endogenous development (Gerace et al., 2019). Intestinal damage includes degenerative alterations in the lamina propria, which is rich in neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages, as well as villous atrophy and epithelial hyperplasia in the villous crypts (Lauwers et al., 2018). Consequently, the absorption surface area and small intestine enzyme activity are decreased. The signs of malabsorption syndrome include protein metabolism, water and electrolyte balance, lactose and enzyme shortages, and excessive diarrhea (Kelly et al., 1996). Ascending intestinal parasites can harm the urogenital tract (Hechenbleikner and McQuade, 2015). Additionally, hematogenous spread is conceivable. Approximately 107 oocytes can infect (Hadfield et al., 2011). Infected humans and animals shed most oocytes in the first week (Gerace et al., 2019). Data on C. parvum and C. hominis indicate that oocytes may continue to shed for weeks beyond the cessation of diarrhea (Shirley et al., 2012). Nonetheless, oocyte excretion has been shown in immunocompetent people infected with C. muris for 7 months (Ali et al., 2024a). The establishment of the genomes of C. parvum and C. hominis, along with the description of over 25 potential virulence factors identified by diverse immunological and molecular approaches, led to significant advancements in the identification of putative virulence factors (Bouzid et al., 2013; Ayan et al., 2024). The immune system lowers the number of thin-walled oocytes and the rate at which type 1 merozoites develop (O’Hara and Chen, 2011). This reduces the chance of autoinfection. A prior infection may lessen the intensity of the illness and the quantity of oocytes produced, but it also lowers resistance to subsequent infections in individuals with a sound immune system (Chappell et al., 1996). Clinical symptomsIn humansThe most frequent intestinal infection species are C. hominis and C. parvum, which cause symptoms such as watery diarrhea, stomach pain, vomiting, nausea, dehydration, and weight loss, despite the fact that 21 species have been linked to human infection (Pal et al., 2021). People with CD4 T cell counts below 150/ml who are exposed to C. parvum suffer from a chronic infection that causes severe and occasionally fatal diarrhea (Khan and Witola, 2023). Those with strong immune systems typically experience self-limiting symptoms, whereas those with compromised immune systems experience the worst symptoms of dehydration and diarrhea (Liu et al., 2023). Furthermore, this illness can be lethal in AIDS patients with compromised immune systems (Sinyangwe et al., 2020). C. hominis produces more severe clinical symptoms in humans than C. parvum, which exhibits oocyte shedding and a longer duration of symptoms (Shirley et al., 2012). In animalsThe animal’s immune system determines the primary symptoms. Cryptosporidiosis is most common in calves younger than 6 weeks (Shaw et al., 2020). The most common symptoms are paste-like to watery diarrhea, followed by fever, dehydration, tiredness, appetite loss, and poor health (Gerace et al., 2019). Most illnesses go away on their own after a few days, although there are wide variations in how animals react to and recover from infections (Ryan et al., 2016). Infection may be lethal in certain situations. Cryptosporidiosis has been linked to elevated rates of morbidity and mortality in sheep and lambs (Ulutaş and Voyvoda, 2004). Common symptoms include diarrhea that ranges from paste-like to watery, yellow, and foul-smelling, as well as anorexia, apathy/depression, and abdominal pain (Sparks et al., 2015). However, animals have also been reported to experience conjunctivitis, pneumonia, sinusitis, dyspnea, and nasal discharge (Robertson et al., 2013). Subclinical infections typically affect animals older than 1 month, while younger animals may also be affected (Santín, 2013). The disease can still affect production, which can result in slower growth, lower carcass weights, lower slaughter percentages, and lower body condition scores (Kifleyohannes et al., 2022). DiagnosisCryptosporidiosis is typically diagnosed by the detection of parasite oocysts, parasite antigen, or parasite DNA in stool samples (Mergen et al., 2020). Since watery diarrhea is the most typical sign of cryptosporidiosis, bacterial, viral, and parasitic enteric infections linked to acute diarrhea—such as rotavirus, coronavirus, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp.—are included in the differential diagnosis for Cryptosporidium (Pawlowski et al., 2009). However, non-infectious causes of gastrointestinal problems, such as inflammatory bowel disease, can also occur in humans (Alsaady, 2024). Cryptosporidiosis is often diagnosed by microscopically detecting oocysts with a diameter of 4–6 μm in an affected subject’s stool (Leitch and He, 2012). However, to rule out Cryptosporidium infection in individuals with severe diarrhea, three stool samples taken on successive days should be microscopically analyzed for oocysts because Cryptosporidium oocyst detection can be challenging (Ramirez et al., 2004). Additionally, samples must be concentrated using the formalin-ether sedimentation method prior to microscopic analysis to identify oocysts in feces (Pacheco et al., 2013). The oocysts of Cryptosporidium can also be observed by phenol-auramine staining of unconcentrated stool smears or acid-fast staining (a modified Ziehl–Neelsen method), where they appear red and brilliant yellow, respectively (Khurana et al., 2012). Oocysts may also appear as “ghost” forms; therefore, this staining needs to be performed carefully (de Oliveira Lemos et al., 2012). Furthermore, although the oocysts of Cryptosporidium are approximately half the size of those of Cyclospora cayetanensis—another coccidian protozoan parasite that infects the human intestine and causes acute diarrhea (approximately 4–5 μm in diameter vs. 9–10 μm)—stool samples must be evaluated with extreme caution because both parasites’ oocysts are autofluorescent and acid-fast (Quintero-Betancourt et al., 2002). Immediate person-to-person fecal–oral transmission is unlikely for C. cayetanensis because its oocysts are not sporulated or infectious when expelled in the feces, despite sharing general life-cycle features with Cryptosporidium (Almeria et al., 2019). Microscopic detection of oocysts in stool smears is the standard method for routine diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis; nevertheless, despite its ease of use and low cost, this method has a low sensitivity (≤30%) (Mittal et al., 2014). Furthermore, the proficiency of the microscopist is crucial for the precise diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis using this method (O’Leary et al., 2021). The sensitivity can be increased using a modified acid-fast stain, which has been linked to a ~55% sensitivity and is frequently used when a structure appears suspect for Cryptosporidium (Garcia et al., 2017). However, this technique is unable to distinguish between distinct Cryptosporidium species. Apart from the previously mentioned techniques, loose or mushy stools can be analyzed for laboratory diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis using a variety of methods, including immunochromatographic assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), which have good sensitivity and specificity for detecting Cryptosporidium antigens (Ghoshal et al., 2018). Although commercial kits are generally more sensitive and specific than microscopic techniques (≈58%–95%), prior research has demonstrated that these antigen/antibody-based detection techniques become less reliable at low parasite burdens (Hawash, 2014). Furthermore, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)—currently recognized by the majority of laboratories as the gold standard for identifying this parasite in stool—is more expensive than antigen-based approaches but offers superior sensitivity and species-level identification. Prior research has demonstrated that immunochromatography assays, microscopy, and ELISA are more time-consuming and less convenient in terms of overall performance (cost, sensitivity, and specificity) compared with PCR (Laude et al., 2016; Autier et al., 2018; Friesen et al., 2018). Accessibility to these molecular approaches is restricted in certain laboratories and nonexistent in others, despite significant advancements in diagnostic tools (such as multiplex PCR assays for the detection of intestinal protozoa). Furthermore, the expense and requirement for technical know-how have restricted the use of these methods, especially in developing nations with high prevalence (Lenière et al., 2024). Figure 2 summarizes the various diagnostic modalities used to detect Cryptosporidium spp. in fecal samples.

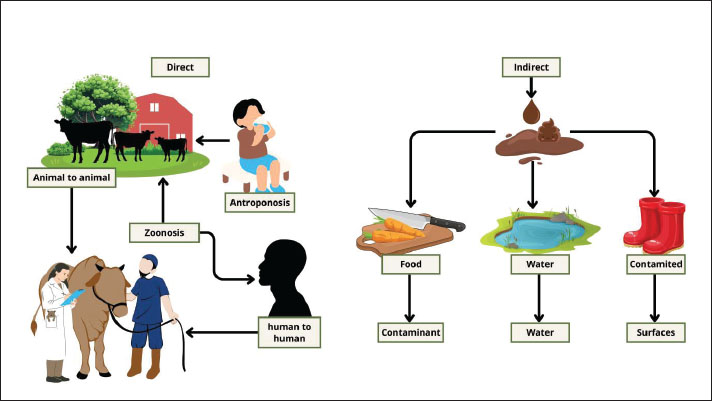

Fig. 2. Diagnostic modalities for fecal detection of Cryptosporidium spp. (A) Acid-fast: adjusted microscopy, highlighting oocyst morphology; (B) quick antigen detection immunochromatographic test; (C) Lugol iodine staining for the identification of oocyst morphology; (D) PCR with sensitive molecular detection; and (E) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detecting specific antibodies or antigens. Various diagnostic methods contain various levels of sensitivity, specificity, and practicality in the field and clinical use. TransmissionThis parasite can spread in two ways: direct transmission and indirect transmission. Cryptosporidium oocysts are excreted in the feces, and they are directly transmitted through inadvertent intake via the fecal–oral pathway (Pumipuntu and Piratae, 2018). Human-to-human transmission typically occurs in swimming pools, water parks, child care facilities, hospitals, and during sexual practices involving oral–anal contact (Hellard, 2003; Ahmed and Karanis, 2020). Transmission can also occur between animals and humans (zoonosis) or vice versa (anthroponosis or reverse zoonosis) (Messenger et al., 2014; Javed and Alkheraije, 2023). Furthermore, direct exposure to infected animals can occur when veterinarians or animal researchers—who are at high risk of contacting infected animals—come into contact with infected calves (Berhanu et al., 2022). Indirect transmission can occur when food supplies, food ingredients, drinking water, and various items, such as clothing and footwear, used on farms or in wildlife parks come into contact with infected human or animal excrement (Ali et al., 2024b). The parasite is transmitted via feces and can infect and reside on the intestinal epithelium surface in humans and other vertebrates (Di Genova and Tonelli, 2016). It can then contaminate soil and water sources, including ponds, rivers, wastewater, sewage, or slurry, and even many water containers, particularly public water supplies that are not adequately treated (Bilal et al., 2024). Distribution and transmission can increase following flooding and intense rainfall (Wamsley et al., 2025). Ingestion of an oocyst containing four sporozoites typically initiates infection in both humans and animals. These complex zoonotic and environmental transmission pathways are illustrated in Figure 3.