| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3549-3557 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(8): 3549-3557 Research Article The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimpSultan Fadel Al-Haid1, Omar H. Amer2, Sameh A. El Alfay3, Enas A.M. Ali4, Hesham Ismail1* and Sherief M. Abdel-Raheem11Department of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al-Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt 3Department of Parasitology, Animal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Benha Branch, Agriculture Research Center (ARC), Giza, Egypt 4Food Hygiene Department, Animal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Benha Branch, Agriculture Research Center (ARC), Giza, Egypt *Corresponding Author: Hesham Ismail. Department of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al-Hofuf, Saudi Arabia. Email: hismail [at] kfu.edu.sa Submitted: 18/05/2025 Revised: 07/07/2025 Accepted: 20/07/2025 Published: 31/08/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

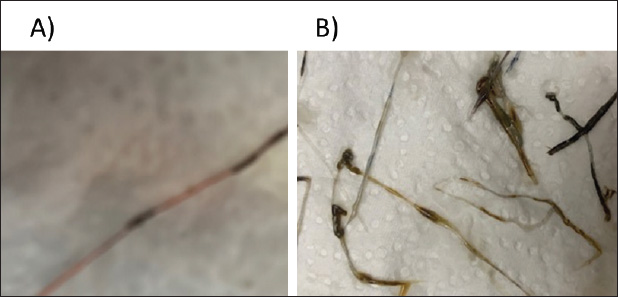

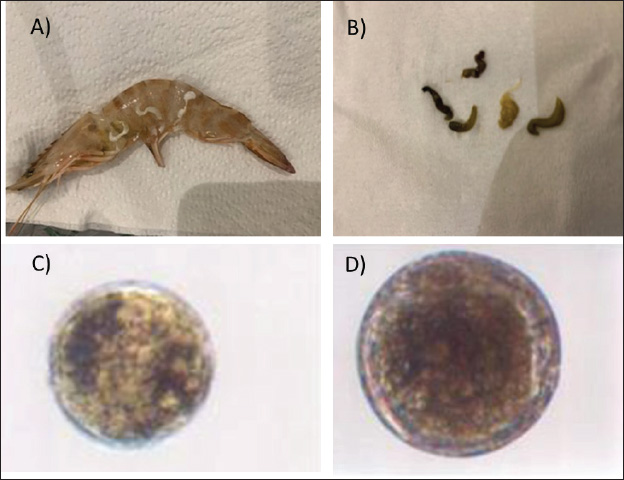

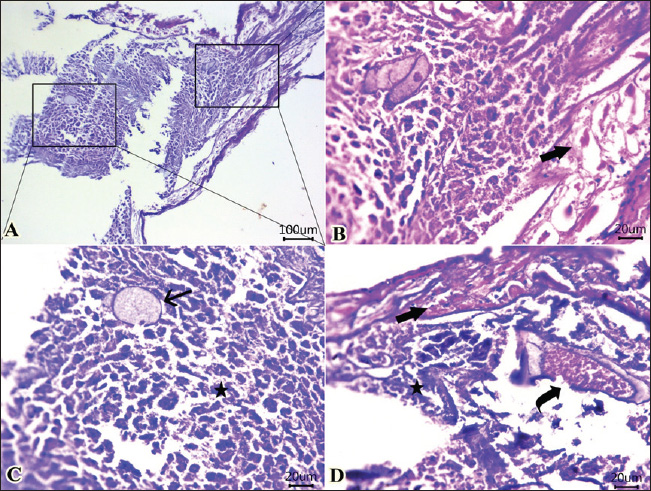

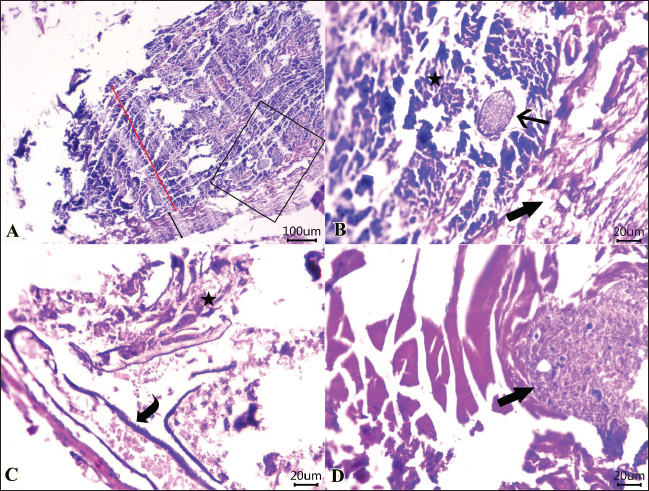

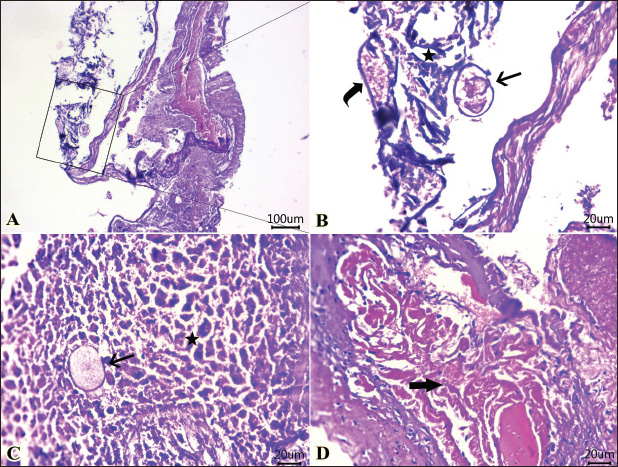

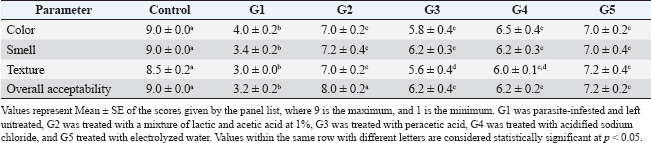

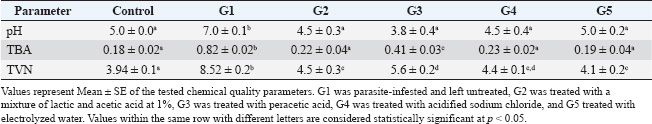

ABSTRACTBackground: Shrimp is one of the most delicious seafoods, with high nutritive values, including high protein content, omega-3 fatty acids, minerals, and trace elements. However, shrimp are liable for several parasitic infestations. Aim: This study examined parasitic infestation in retailed shrimp in Egypt. The histopathological and sensory effects of parasite infestation on shrimp were also examined. The parasite-inhibiting and shrimp-sensory-improving actions of organic acids were also explored. Methods: Samples of 200 shrimp were collected from retail markets in Kalyobia Governorate, Egypt. The parasitic infestation of the collected shrimp samples was examined, and the sensory and histopathological changes were investigated. Thiobarbeturic acid (TBA), total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN), and pH were also measured. In a protection trial, the use of a mixture of 1% lactic and acetic acid, peracetic acid, acidified sodium chloride, and electrolyzed water was tested for their ameliorative effects. Results: This investigation showed that parasitic infestation was recorded at 25% (50 of 200 samples). The contaminated shrimp had bleeding, empty stomach, midgut, and pale hepatopancreas. Additional parasite identification indicated that the shrimps were infected with Mysidobdella sp., Microphallid trematode (Microphallus), and Prohemistomum metacercaria. Intestinal sections indicated that necrotic enteritis with rounded to oval formations “are parasitic elements” between necrotic and detached enterocytes. Parasite-infested shrimp had lower color, smell, texture, and overall acceptability than noninfested shrimp. Treatment with organic acids, their salts, and electrolyzed acidic water significantly improved sensory properties. All treatments significantly improved TBA, TVBN, and pH toward the acidic side. Conclusion: Such acids should be used during shrimp processing to improve their sensory, chemical, and antiparasitological properties. Keywords: Parasites, Shrimp, Organic acids, Chemical quality, Food safety. IntroductionShrimp is widely regarded as one of the most delectable varieties of seafood, and it is a tasty dish that is consumed in many nations, including India, China, and Egypt. Shrimp is considered an innovative source of high biological value protein, with a protein content of 19.2%, moisture content of 75.3%, carbohydrate content of 3.6%, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, minerals such as calcium and phosphorus, and vitamins, including vitamin D. Crustaceans exhibit high levels of the amino acids alanine, arginine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, glycine, and lysine, with amounts reaching 8.1%, 7.1%, 7.7%, 10.7%, 4.5%, and 5.5%, respectively, in terms of the percentage of total protein that they contain (Sidwell, 1981; Hafez et al., 2022). To compensate for the dearth of red meat, the consumption of fish and shellfish has increased worldwide, particularly in Egypt. Furthermore, shrimp are subjected to a wide range of pathogens, including parasites, which can be found in their environment throughout their lives (Al-Sultan et al., 2025). The rapid growth and expansion of the shrimp aquaculture business occurred concurrently with the emergence of several different diseases. The onset of disease results in large losses in shrimp aquaculture production and international trade, which, in turn, hinders coastal areas’ economic growth. Although it is challenging to collect precise economic statistics regarding the impact of illness on shrimp production, it is estimated that the annual losses of shrimp production owing to disease amount to approximately 40%, which is equivalent to nearly three billion dollars in economic value (Asche et al., 2021). Despite the fact that the shrimp aquaculture industry has been expanding worldwide, it continues to be plagued by a variety of diseases, including those caused by viruses, parasites, bacteria, and fungi, which result in the death of a large number of shrimp (Yu et al., 2022). Salts of low molecular weight organic acids, such as citric, lactic, and acetic acid, have been utilized in several food systems to control the growth of microorganisms, enhance sensory qualities, and extend the shelf life of food. Organic salts of acetate, lactate, and citrate possess antibacterial properties against various foodborne pathogens. In addition, these salts have a suppressive effect on the growth of potential food spoilage microorganisms. Additionally, these salts are readily available, inexpensive, and generally “recognized-as-safe” (Sallam, 2007). In view of the previous facts, this study was undertaken to investigate the prevalence of parasitic infestation of retailed shrimp in the Governorate of Kalyobia, Egypt. In addition, the histopathological effects and sensory alterations of such parasitic infestation on shrimps were investigated. The inhibitory effects of organic acids against such parasites and their ameliorative effects on the sensory characteristics of shrimp were further examined. Materials and MethodsSample collectionSamples of 200 shrimp were collected from retail markets in the Kalyobia Governorate, Egypt. Specimens were brought back on ice to the parasitology laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, and examined for parasites immediately or stored at 20°C for later processing. Parasitological examinationTo collect parasites, individual shrimp were submerged in a dish of deionized water. The carapace was then taken from the cephalothoracic cavity using a dissecting microscope, and the organs were removed from the cavity. The hepatopancreas and feeding palps were disassembled to isolate parasites. Additionally, the nerve cord was removed from the entire length of the shrimp, flattened between two slides, and examined using a compound microscope at a total magnification of 100. The contents of the stomach, intestine, and hindgut were examined after the anterior cecum was removed from the digestive tract and opened along with the other organs in the digestive tract. To study the abdominal muscle, a squash of approximately 1–2 mm2 was placed between two slides and analyzed at a total magnification of 100. When the gonads or muscles were infected and stained with Giemsa, smears were performed on the examined samples. For molecular analysis, parasite specimens were preserved in 95% ethanol. Morphotypes of parasite groups were initially defined using morphological traits and infection locations (Deardorff and Overstreet, 1981). This was done because the morphological identification of larval parasites can be difficult. By using fresh tissue scrapings with a drop of sterile physiological saline water (0.85% NaCl), covering them with a clean cover slip (wet mount preparation), and examining them under a light microscope, we identified the endoparasites that were present on the hepatopancreas and midgut. To create stained smears, tissue scrapings were collected from the hepatopancreas and midgut and placed on clean slides. The scrapings were then smeared, air-dried, and fixed in an acetone-free methanol solution. Finally, the tissue was stained with either Giemsa (Chakraborty and Bandyopadhyay, 2010) or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Lightner, 1996). The slides were examined using a light microscope to observe the gregarine (Chakraborty and Bandyopadhyay, 2010) and vermiform (Sriurairatana et al., 2014) species. Examination of shrimp for encysted metacercariaeMacroscopic examinationIt was performed either by the naked eye or with the aid of a magnifying hand lens (Mahdy et al., 1995). Microscopic examinationMicroscopic examination was performed to determine encysted metacercariae in different parts of the shrimp body and musculature using the compression technique and artificial tissue digestion method. The larvae were viewed under a magnification power of ×100 and ×400. The muscle compression techniqueThe viscera and fish musculature of each shrimp were compressed between two glass slides and examined under a dissecting microscope according to the method described by Park et al. (2004). Artificial tissue digestion techniqueAccording to García Hernández (2001), the whole musculature, viscera, and tissue of each examined shrimp were weighed, ground using a blender, and then added to artificial digestive fluid [Pepsin 5g, HCl concentrated) 7 ml, and distilled water up to 1,000 ml] at a rate of l part fish tissue to 20 parts digestive fluid in a flask and incubated at 37°C for 12–24 hours. The whole mixture was placed in small Petri dishes and encysted. Metacercariae were collected under a microscope. A microphoto was taken for each type of encysted metacercariae. Histopathological examinationAfter being fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin for 24 hours, the specimens obtained from the intestines of shrimps were dehydrated in escalating grades of alcohol, cleaned in xylene, and finally embedded in melted paraffin wax. Paraffin slices with a thickness of 5 µm were produced using a microtome (Leica®) and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Suvarna et al., 2018). Sensory analysisA panel of 10 judges assessed samples for sensory attributes, including color, smell, texture, and overall acceptability, using a 9-point hedonic scale. A score of 9 indicated the highest acceptability, while 1 indicated the lowest (Erickson et al., 2007). Chemical quality analysisThiobarbeturic acid (TBA) was determined following the method of Ismail et al. (2008). Total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN) was measured according to Pearson (1976), and pH was determined using the methodology described by Yalcin et al. (2018). Trial of protection using organic acidsIn a protection trial, infested shrimps were grouped into five groups (n=5 per group), where group 1 (G1) was left untreated, G2 was treated with a mixture of lactic and acetic acid at 1%, G3 was treated with peracetic acid, G4 was treated with acidified sodium chloride, and G5 treated with electrolyzed water. All treatments were conducted by immersion in the treatment solution for 30 minutes (Mine and Boopathy, 2011). A control group of the normal uninfected shrimps was used for comparison. The sensory characteristics and chemical quality parameters were further measured. Statistical analysisQuantitative data are reported as mean ± SE. A one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison test was used to determine the significant differences between the groups. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ethical approvalExperiments were performed according to the ethical guidelines of Zagazig University, Egypt, with ethical approval number ZU-IACUC/2/F/298/2024. ResultsThe results of this study revealed that 50% of the 200 examined shrimp samples were infested with parasites at 25%. The infested shrimp showed hemorrhage with empty stomach, empty midgut, and pale hepatopancreas (Fig. 1). Further identification of the parasites revealed that the shrimps were infected with Mysidobdella sp., Microphallid trematode (Microphallus sp.,), and Prohemistomum metacercaria (Fig. 2). Examined sections from the intestine (Fig. 3) showed necrotic enteritis with the presence of rounded to ovoid-shaped structures “may be parasitic elements” in between necrotic and detached enterocytes. Moreover, extensive myonecrosis is observed at the muscular layer and congested vasculature. Sections from the intestine (Fig. 4) showed necrotic epithelial lining mucosa beside the vacuolated and necrotic muscular layer. “Oval-shaped protozoal element” were also embedded between the necrotic columnar mucosal epithelium. Furthermore, congestion and hemorrhages within the mucosal and submucosal layers, as well as myolysis within the musculosa, were also detected. Other sections from the intestine (Fig. 5) revealed a “parasitic element” encircled by a capsule within the necrotic intestinal mucosa beside dilated blood vessels. Protozoal elements were observed between the necrotic columnar epithelium, which was accompanied by degenerated inflammatory cells. Hyalinized or degenerated muscular layers were also observed. The results recorded in Table 1 showed that the parasite-infested shrimps showed significant reduction (p< 0.05) in the tested sensory characteristics, including color, smell, texture, and overall acceptability, compared to the non-infested shrimp. Interestingly, treatment with different organic acids and their salts and EW showed a significant improvement in the examined sensory characteristics. All treatments showed significant improvement in the tested chemical quality parameters, including TBA, TVBN, and pH (Table 2). DiscussionThe shrimp aquaculture business has been constantly expanding because of the growing demand for shrimp and the advancement of aquaculture technology. Frequent infections have emerged as a significant risk factor for shrimp aquaculture over the past several years. These diseases have resulted in a significant decrease in shrimp production and economic value loss for the nation (Yu et al., 2022). Among such diseases is parasitic infestation. In the current study, parasitic infestation was remarkable in the examined samples. Parasitic infestation was obvious in cultured and wild shrimp in Mexico at rates that varied from 7% to 90%, respectively. The cestode Prochristianella hispida and the gregarines Cephalolobus penaeus and Nematopsis penaeus were the most dominant species (Chávez-Sánchez et al., 2002). One of the developing pathogens for penaeid shrimp is Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP), a microsporidian parasite. It has been reported that EHP is associated with growth retardation in farmed shrimp, and it has been discovered in a number of Asian nations that are involved in shrimp farming, including Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and China (Tang et al., 2015). Leeches have also been found attached to shrimp in Norway (Karlsbakk, 2005). The leeches are visible and connected to the fins, tail, body, operculum, mouth, and eyes of fish. They may also adhere to the body. The findings of Vaughan et al. (2018), which claim that leech infection was discovered in the external section of the fish and generated hemorrhages that led to secondary bacterial infection, are consistent with the findings of certain fishes, which displayed hemorrhagic on their body surfaces. Ravi and Yahaya (2017) found that the most common consequences of leech infection in fish are the occurrence of local bleeding and ulceration in the tissues of the fish. This species is linked to the host by using anterior and posterior suckers. Such parasites caused marked histopathological alterations, which were clear in the current investigation. The presence of Probopyrus bithynis, which belongs to the family Bopyridae, was likely responsible for the histopathological changes observed in the gills of Macrobrachium amazonicum. A single pair of parasites, both male and female, was responsible for the infestation of P. bithynia in each and every case. The infestation occurred on either the right or left side of the branchial chamber, and the gill structures were visibly compressed as a result of the presence of the parasites. A chronic inflammatory response was observed in the gills of M. amazonicum parasitized by P. bithynia. This response was characterized by the presence of edema, increased quantities of hemocytes, necrosis, epithelial cell hyperplasia, rupture of the pillar cells at the ends of the gill lamellae, desquamation of the cuticle, lamellar fusion, and rupture of the lamellar epithelium. Histological sections of the parasitized M. amazonicum gills revealed tissue lesions. The presence of P. bithynia can produce structural changes in the branchial chamber of the host, which can then lead to physiological changes that compromise the respiratory capacity of the host. Finally, histological changes in the branchial chamber of hosts provide evidence that P. bithynia directly feeds on the gill tissues of this particular shrimp (Corrêa et al., 2018).

Fig. 1. (A) Intestine of shrimps showing hemorrhage. (B) Stomach and intestine of shrimp showing an empty stomach, an empty midgut, significant atrophy, and pale hepatopancreas.

Fig. 2. (A) Shrimp infected by Mysidobdella sp. (Hirudinida: Piscicolidae) leeches. (B) Mysidobdella californiensis (C) Microphallid trematode Microphallus sp. Metacercaria (D) Prohemistomum metacercaria.

Fig. 3. Photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections of shrimp intestine showing: A, B, C, D: rounded to ovoid-shaped structures “may be parasitic elements” (arrow) between necrotic and detached enterocytes (star), extensive myonecrosis at the muscular layer (thick arrow), and congested vasculature (curved arrow). (Scale bar 100 μm, and high magnification, 20 μm). In the current investigation, parasitic infestation in the shrimp caused significant alterations in the meat’s sensory and chemical quality. This was apparent by the elevation in the pH, trimethylamine (TMA), and TVBN, confirming the degradation of both protein and lipids and affecting the sensory characteristics when the sensory scores were significantly reduced compared with the non-infested shrimps. Hanan and Tadros (2019) reported that isopods markedly reduced the sensory attributes and chemical quality of retailed fish in Manzala Lake at Port-Said Governorate, Egypt.

Fig. 4. Photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections of the intestine of shrimp showing: A, B, C, D: Protozoal element (arrow) in between necrotic columnar mucosal epithelium (star), congestion (curved arrow), hemorrhages within the mucosal and submucosal layers, and extensive myonecrosis (thick arrow) at the muscular layer. (Scale bar 100 μm, and high magnification 20μm). (“Red double-headed arrow” refers to mucosa and submucosa, while, “black double-headed arrow” refers to muscular layer). Organic acids and their salts were used in an experimental trial to improve the sensory characteristics and chemical quality of the parasite-infested shrimps. Interestingly, all used treatments significantly improved the sensory and chemical quality of the infested shrimps, in particular the combination of lactic and acetic acid 1% and the electrolyzed acidic water. In agreement with these results, Sallam (2007) conducted a study to determine the shelf life, chemical quality, and sensory characteristics of salmon slices that were treated by dipping them in an aqueous solution of sodium acetate (NaA), sodium lactate (NaL), or sodium citrate (NaC) at a concentration of 2.5% while being stored in the refrigerator. The treated salmon slices exhibited a considerable decrease in the K value, hypoxanthine (Hx) concentration, tTVBN, and TMA concentrations compared with the control, as revealed by the chemical analyses. The treated salmon received sensory scores that were within the reference range for appearance, juiciness, and tenderness compared to the control group. Some panellists could identify only minimal changes in the sensory characteristics of samples treated with NaA and NaL. It has been estimated that salmon treated with NaL, NaC, and NaA will have a shelf life of 12, 12, and 15 days, respectively, but the control will only have a shelf life of 8 days. As a result, the salts of organic acids are suitable for use as environmentally friendly preservatives for fish kept in the refrigerator.

Fig. 5. Photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections of the intestine of shrimp showing: A, B, parasitic element” encircled by capsule (arrow) within the necrotic intestinal mucosa (star), dilated blood vessel (curved arrow). C, D: Protozoal element (arrow) between the necrotic columnar epithelium accompanied by degenerated inflammatory cells (star). Hyalinized or degenerated muscular layer (thick arrow) in the muscular layer. (Scale bar 100 μm, and high magnification 20 μm). Table 1. Ameliorative effects of the organic acids and their salts on the sensory characteristics of the tested shrimp samples.

Table 2. Ameliorative effects of the organic acids and their salts on the Ph, TBA, and TVN of the tested shrimp samples.

ConclusionThis study indicated a 25% parasitic infestation of retailed shrimp in the Kalyobia Governorate, Egypt. This infestation caused a drastic reduction in the sensory characteristics and chemical quality of the infested shrimps. However, dipping the infested shrimp in organic acid solutions, particularly the combination of lactic and acetic acid 1%, and electrolyzed acidic water caused significant improvement in the sensory and chemical qualities of the shrimp. Therefore, it is highly recommended that such acids be used as a dipping solution for shrimp during its preparation to improve its sensory, chemical, and parasitological qualities. AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU252657]. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. FundingThis work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU252657]. Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed equally. Data availabilityAll related data are included in the manuscript. ReferencesAl-Sultan, S.I., El-Bahr, S.M., Darwish, W.S., Meligy, A.M., El Sebaei, M., Mohamed, M.H., Megahed, A. and Elzawahry, R.R. 2025. Potential toxic elements in edible shrimp and other edible parts: a health risk assessment. Open Vet. J. 15(2), 1024. Asche, F., Anderson, J.L., Botta, R., Kumar, G., Abrahamsen, E.B., Nguyen, L.T. and Valderrama, D. 2021. The economics of shrimp disease. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 186, 107397. Chakraborty, T. and Bandyopadhyay, S. Identification of reduplication in Bengali corpus and their semantic analysis: a rule based approach. In Proceedings of the 2010 Workshop on Multiword Expressions: from Theory to Applications, 2010, p 73–76. Chávez‐Sánchez, M.C., Hernández‐Martínez, M., Abad‐Rosales, S., Fajer‐Ávila, E., Montoya‐Rodríguez, L. and ÁLvarez‐Torres, P. 2002. A survey of infectious diseases and parasites of penaeid shrimp from the Gulf of Mexico. J. World Aquac. Soc. 33(3), 316–329. Corrêa, L.L., Oliveira Sousa, E.M., Flores Silva, L.V., Adriano, E.A.., BritoOliveira, M.S.. and Tavares-Dias, M. 2018. Histopathological alterations in gills of Amazonian shrimp Macrobrachium amazonicum parasitized by isopod Probopyrus bithynis (Bopyridae). Dis. Aquta. Organ. 129(2), 117–122. Deardorff, T.L. and Overstreet, R.M. 1981. Larval hysterothylacium (=Thynnascaris) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) from fishes and invertebrates in the Gulf of Mexico. Proceed. Helminthol. Soc. Washin. 48(2), 113–126. Erickson, M.C., Bulgarelli, M.A., Resurreccion, A.V.A., Vendetti, R.A. and Gates, K.A. 2007. Sensory differentiation of shrimp using a trained descriptive analysis panel. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 40(10), 1774–1783. García Hernández, M.P., Lozano, M.T., Elbal, M.T. and Agulleiro, B. 2001. Development of the digestive tract of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L). Light and electron microscopic studies. Anatom. Embryol. 204, 39–57. Hafez, A.E.S.E., Elbayomi, R.M., El Nahal, S.M., Tharwat, A.E. and Darwish, W. 2022. Potential hazards associated with the consumption of crustaceans: the Egyptian scenario. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 12, 811–814. Hanan, A.A. and Tadros, S.W. 2019. Relationship between isopods parasite infestation and fish quality. J. Egypt. Vet. Med. Assoc. 79, 1007–1027. Ismail, H.A., Lee, E.J., Ko, K.Y. and Ahn, D.U. 2008. Effects of aging time and natural antioxidants on the color, lipid oxidation and volatiles of irradiated ground beef. Meat Sci. 80(3), 582–591. Karlsbakk, E. 2005. Occurrence of leeches (Hirudinea, Piscicolidae) on some marine fishes in Norway. Mar. Biol. Res. 1(2), 140–148. Lightner, D.V. 1996. Epizootiology, distribution and the impact on international trade of two penaeid shrimp viruses in the Americas. Rev. Sci. Tech. 15(2), 579–601. Mahdy, O.A., Manal, M., Essa, A.A. and El-Easa, M. 1995. Parasitological and pathological studies on heterophyid infection in Tilapia species from Manzala Lake, Egypt. J. Comp. Pathol. Clin. Pathol. 8, 131–145. Mine, S. and Boopathy, R. 2011. Effect of organic acids on shrimp pathogen, Vibrio harveyi. Curr. Microbiol. 63, 1–7. Park, J.H., Guk, S.M., Kim, T.Y., Shin, E.H., Lin, A., Park, J.Y. and Chai, J.Y. 2004. Clonorchis sinensis metacercarial infection in the pond smelt Hypomesus olidus and the minnow Zacco platypus collected from the Soyang and Daechung Lakes. Korean J. Parasitol. 42(1), 41. Pearson, D. 1976. The chemical analysis of foods, 7th ed. Harlow, UK: Longman Group Ltd Inc. Ravi, R. and Shariman Yahaya, Z. 2017. Zeylanicobdella arugamensis, the marine leech from cultured crimson snapper (Lutjanus erythropterus), Jerejak Island, Penang, Malaysia. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Biomed. 7(5), 473–477. Sallam, K.I. 2007. Chemical, sensory and shelf life evaluation of sliced salmon treated with salts of organic acids. Food Chem. 101(2), 592–600. Sidwell, V.D. 1981. Chemical and nutritional composition of finfishes, whales, crustaceans, mollusks, and their products. Minneapolis, MN: US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service. University of Minnesota, vol. 55. Sriurairatana, S., Boonyawiwat, V., Gangnonngiw, W., Laosutthipong, C., Hiranchan, J. and Flegel, T.W. 2014. White feces syndrome of shrimp arises from transformation, sloughing and aggregation of hepatopancreatic microvilli into vermiform bodies superficially resembling gregarines. PLoS. One. 9(6), e99170. Suvarna, K.S., Layton, C. and Bancroft, J.D. 2018. Bancroft’s theory and practice of histological techniques. Beijing, China: Elsevier Health Sciences. Tang, K.F., Pantoja, C.R., Redman, R.M., Han, J.E., Tran, L.H. and Lightner, D.V. 2015. Development of in situ hybridization and PCR assays for the detection of Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP), a microsporidian parasite infecting penaeid shrimp. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 130, 37–41. Vaughan, D.B., Grutter, A.S. and Hutson, K.S. 2018. Cleaner shrimp are a sustainable option to treat parasitic disease in farmed fish. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 13959. Yalcin, H., Konca, Y. and Durmuscelebi, F. 2018. Effect of dietary supplementation of hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) on meat quality and egg fatty acid composition of Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl).102(1), 131–141. Yu, Y.B., Choi, J.H., Kang, J.C., Kim, H.J. and Kim, J.H. 2022. Shrimp bacterial and parasitic disease listed in the OIE: a review. Microb.ial Pathogen.esis 166, 105545. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Al-haid SF, Amer OH, Alfay SAE, Ali EA, Ismail H, Abdel-raheem SM. The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 Web Style Al-haid SF, Amer OH, Alfay SAE, Ali EA, Ismail H, Abdel-raheem SM. The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=271724 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Al-haid SF, Amer OH, Alfay SAE, Ali EA, Ismail H, Abdel-raheem SM. The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Al-haid SF, Amer OH, Alfay SAE, Ali EA, Ismail H, Abdel-raheem SM. The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(8): 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 Harvard Style Al-haid, S. F., Amer, . O. H., Alfay, . S. A. E., Ali, . E. A., Ismail, . H. & Abdel-raheem, . S. M. (2025) The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. Open Vet. J., 15 (8), 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 Turabian Style Al-haid, Sultan Fadel, Omar H. Amer, Sameh A. El Alfay, Enas A.m. Ali, Hesham Ismail, and Sherief M. Abdel-raheem. 2025. The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 Chicago Style Al-haid, Sultan Fadel, Omar H. Amer, Sameh A. El Alfay, Enas A.m. Ali, Hesham Ismail, and Sherief M. Abdel-raheem. "The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Al-haid, Sultan Fadel, Omar H. Amer, Sameh A. El Alfay, Enas A.m. Ali, Hesham Ismail, and Sherief M. Abdel-raheem. "The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp." Open Veterinary Journal 15.8 (2025), 3549-3557. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Al-haid, S. F., Amer, . O. H., Alfay, . S. A. E., Ali, . E. A., Ismail, . H. & Abdel-raheem, . S. M. (2025) The extent of some integration between organic acids and compounds in controlling parasitic infestation of shrimp. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3549-3557. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.17 |