| Review Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(1): 35-53 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(1): 35-53 Commentary Article Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulatesMassimo Giangaspero1,2* , Salah Al Mahdhori3, Sultan Al Bulushi3 , Ali Salim Bait Said4 and Metab Khalaf Salim Al Ghafri31Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Teramo, Teramo, Italy 2Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean, Center for Global Studies, San Marino, Republic of San Marino 3Environment Authority, Muscat, Oman 4Environmental Conservation Office in Dhofar, Salalah, Oman *Corresponding Author: Giangaspero Massimo. Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean, Center for Global Studies, San Marino. Email:giangasp [at] gmail.com Submitted: 11/12/2023 Accepted: 05/12/2024 Published: 31/01/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

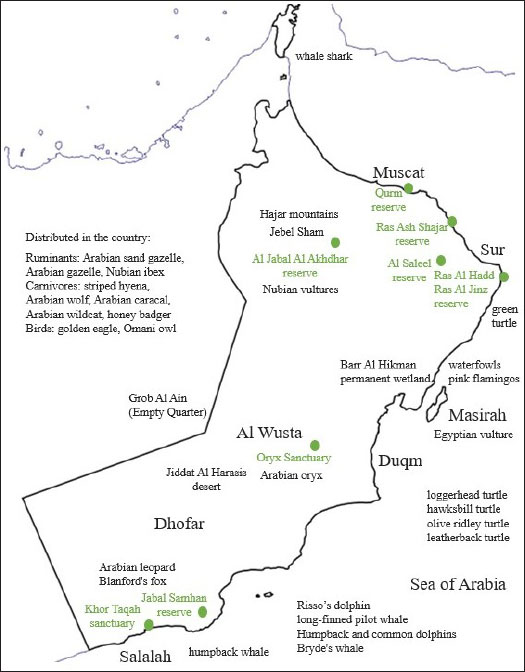

AbstractIn order to achieve optimal health for humans, animals, and our environment, the ‟One Health” approach proactively engages various disciplines, including environmental health sciences, veterinary medicine, and human medicine. Therefore, wildlife conservation assumes a relevant role in this context. The Sultanate of Oman is a country with an immense biodiversity. In recent decades, authorities have actively protected wildlife and the natural environment. In 1994, the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary was created under the patronage of the Royal Diwan. The Environment Authority was recently established, and the plan “Vision 2040” was conceived with the ambitious goal of Oman becoming one of the top 20 countries for wildlife protection. Two species, in particular, show the amplitude of the efforts necessary to preserve this natural heritage and their survival: the oryx of Arabia and the green turtle. The oryx is not only a national symbol but, from extinction in nature, its return is also a success for the Omani sanctuary. The green turtles elected the Omani coasts as the second reproduction site in the world. Therefore, the delicate equilibrium of wild fauna in Oman is required to be studied and supported. Keywords: Preservation, Sultanate of Oman, Vulnerable species, Wild fauna. IntroductionThe Sultanate of Oman is a country that surprises by its extraordinary diversity of exceptional animals. Oman’s varied landscapes and unusual climatic conditions have created an extraordinary biodiversity. Oman is home to one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. Peaceful sea giants emerge along its shores, and unique wild animals have settled in its mountains and deserts. For the animals, life in Omani’s mountains is a challenge in itself, but some have been able to develop special skills to withstand the hostile conditions of this ecosystem. The most spectacular and charismatic animal of Oman is undoubtedly the Arabian leopard ( Panthera pardus nimr, Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1833), one of the smallest species of leopard in the world (Spalton and Hikmani, 2014). The mountains are home to other rare species, such as the striped hyena ( Hyaena hyaena, Linnaeus, 1758), which is of modest size and has a declining population (CBD, 2014). At the turn of the rare water points, meet the most different creatures and the shallow waters are the playground of the humpback whale ( Megaptera novaeangliae, Borowski, 1781) of the Arabian Sea. Historically, in Oman was present also the Asiatic lion ( Panthera leo persica, Meyer, 1826) (Mallon and Budd, 2011). However, severe changes occurred in the region, showing changes in the fauna of Oman, especially in the context of the last century. The disappearance of selected species such as the Arabian oryx ( Oryx leucoryx, Pallas, 1777), in 1972 (Spalton, 1993), and the Asiatic cheetah ( Acinonyx jubatus venaticus, Griffith, 1821), in 1977 (Harrison, 1983), were indicative of these marked changes and serious threats affecting the natural environment of the country. Fortunately, for the Arabian oryx, it was possible to reintroduce, at least in captivity, the animal in the country (Spalton, 1993). Field observations and scientific studies have been undertaken about Oman’s wildlife, producing some literature and publications. Despite past studies, Oman remains a country of wild nature still largely unknown. The present article aims to provide an overview of the value of the wild fauna in the Sultanate and indicate conservation efforts and future prospects to address threats and challenges, with particular attention to the Arabian oryx and sea turtles. Study RegionThe Sultanate of Oman is a relatively wide territory, with about 300,000 square km, in the south of the Arabian Peninsula, characterized by two main tracts: the arid desert and rocky mountains and the long coastline on the Arabian Sea, the northwestern section of the Indian Ocean. Exception made for the microclimate specific to the south occidental area of the governorate of Dhofar, capital Salalah, one-third of the country neighbor to the border with Yemen, where rainfall (annual average of 250 mm) allows luxuriant vegetation and it is favorable to agriculture; the rest of the country is characterized by a subtropical dry climate, with an average of annual rainfall 59 mm and temperature average of 27°C, from 25°C in January and 40°C in June (but temperature may exceed 50°C) (Ministry of Agriculture, 2011; World Bank, 2021). A large part of the territory consists of arid surfaces and desert expanses. The Rub Al Khali (Grob Al Ain or Empty Quarter), the world’s largest continuous sand desert (https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/), covers the southern part of the peninsula. Still, some areas challenge dryness with landscapes as surprising as the fauna present. Mount Samhan (Jabal Samhan), located in the mountains of Dhofar is one of these places. The long coastal plain is surmounted by mountains that rise to 1,000 m. Oman benefits from a strategic position at the intersection of Africa, Asia, and Europe. Its coastline opens to the north of the Indian Ocean. Its geographical peculiarities offer areas of rest much appreciated by migratory birds, and local species also find their well-being. The secret of this diversity is the wind. With summer comes the khareef, the monsoon. The monsoon season starts from June until September, leading to heavy and beneficial rainfalls, especially encountering high mountains. From the Indian Ocean, it blows toward the land and sweeps the mountains of Dhofar. This explains why the region of Dhofar accounts for 80% of Oman’s biodiversity and probably the Arabian Peninsula. In addition, tropical cyclones seldom contribute to heavy rainfalls, as the cyclone Tej which was expected to unleash 200 to 300 mm of rain in Dhofar governorate in 3 days, in October 2023 (Gulf News, 2023). In addition, in the Hajar northern mountains, located on the northeast corner of the Arabian Plate, from the Musandam Peninsula to the east coast of Oman, pluviometry may reach 460 mm (Sherif et al., 2014). The rain gives new life to this arid landscape. The wadis fill with water. These often dry streams have dug passages between the limestone rocks. As soon as the wadis are filled, the fish, sleeping in the pockets of water deeply hidden in the soil, resume their activities. Freshwater fish are few and far between in Oman. Vegetation is also reborn and covers rocky slopes and mountain paths. It is the domain of particularly stealthy animals, some of which can only be observed rarely and in the most remote places, such as the Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr) and the wolf of Arabia ( Canis lupus arabs, Pocock, 1934). In the south of the Sultanate, the khareef, the powerful summer monsoon, not only revives the vegetation but also, before reaching the coast, has already accomplished a feat. In the Sea of Arabia and up to the southeast coast of Oman, the khareef activates a nutrient-rich sea stream. Surface warm water creates a vacuum filled by the depths’ cold-water masses, defined as upwelling. This rare phenomenon is found only in four regions of the world (Kampf and Chapman, 2016). Thanks to cold currents, the water temperature passes below the threshold of 20°C, perfect conditions for kelp growth. In Oman, this phenomenon, despite declining, occurs only in the Dhofar (Coleman et al., 2022). The kelp grows during the monsoons and invades the coral reef. It usually grows in colder regions, but the fresh and nutritious water supply allows it to develop here. Even plankton finds an ideal habitat and develops widely, and all other marine living beings, even large marine mammals, find benefit. In Figure 1, a study region map, are shown the areas of nature reserves and also the approximative wildlife distribution in the Sultanate. Conservation Efforts and Research HistoryWith concern to conservation efforts, the Oryx Sanctuary (formerly known as Al Wusta Wildlife Reserve - WWR) was the first wildlife reserve in Oman and the most relevant protected area created in the country. It was established in 1980 for the reintroduction and breeding of the Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) (Fig. 2) (Spalton, 1993). The Arabian Oryx Sanctuary is an area within Oman’s Central Desert and Coastal Hills biogeographical regions. Seasonal fogs and dews support a unique desert ecosystem whose diverse flora includes several endemic plants (Patzelt, 2015). Its rare fauna includes the first free-ranging herd of Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) since the global extinction of the species in the wild in 1972 and its reintroduction here in 1982. The only wild breeding sites in Arabia of the endangered houbara bustard ( Chlamydotis undulata, Jacquin, 1784), a species of wader, are also to be found, as well as Nubian ibex ( Capra nubiana, Cuvier, 1825) (Fig. 3), Arabian wolves (Canis lupus arabs), honey badgers ( Mellivora capensis, Schreber, 1776), caracals ( Caracal caracal schmitzi, Matschie, 1912), and the largest wild population of Arabian gazelle ( Gazella arabica, Lichtenstein, 1827) (Fig. 4). In 1994, the sanctuary was inscribed in the list of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Centers (Dossier number 654), based on the criterium of a property of 2,750,000 ha, containing the most important and significant natural habitats for in situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation (UNESCO, 2022). However, in 2007, the sanctuary was delisted due to a 90% reduction of the protected area in favor of hydrocarbon prospections (UNESCO, 2007). Recently, the activity of the reserve was extended to other wildlife breeding, which includes the Arabian sand gazelle ( Gazella marica, Thomas, 1897), also called Reem gazelle (Fig. 5), the Arabian gazelle (Gazella arabica), and the Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana). These antelopes are only kept in a few countries worldwide.

Fig. 1. Sultanate of Oman: study region map: areas of nature reserves and indicative wildlife distribution. Another important activity for protecting wild fauna is focused on sea turtles. Ras Al Hadd and Ras Al Jinz, in Ash Sharqiyah district, are monitored reproduction sites of green turtles ( Chelonia mydas, Linnaeus, 1758) (Fig. 6) under the competence of the Environment Authority and in collaboration with the Ministry of Tourism and the Oman Tourism Development Company (OMRAN), a government-owned company. The sites are located on the Oman coast on the Indian Ocean, which includes a strategic 142 km, with several female turtles arriving every night, especially during the peak period. Oman is the second reproduction site in the world for marine green turtles (Chelonia mydas), after Australia (Dobbs, 2007). At the Al Ras Hadd station beach of 7 km, surveillance is ensured by 11 rangers and two staff from the Ministry of Tourism, operating in groups of four. Activities encompass monitoring the reproduction site, marking, and measurements, education, assistance to laying females and hatching turtles, and evacuation of turtle carcasses. From 6 pm to 5.30 am, access to beaches within a range of 300 mt from the seashore is forbidden. Human presence and activities are restricted to the local community of fishermen. Two staff groups start at 5.30 pm rounds to warn people to leave the site, informing briefly about the exigences of female turtles during the delicate lying season (June-September – peak June-July), so undertaking basic divulgation/education activities against main disturbance factors (e.g., presence of persons, vehicles, and lights). During the night, the staff observe most of the arrivals beginning after 9 pm. Five to six females per day are tagged and measured (to determine the age). In 40 years, 66,616 tags have been used.

Fig. 2. Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) at Al Wusta natural reserve. In 2021, the Sanctuary hosted 738 oryx. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

Fig. 3. Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana) held in captivity at Al Wusta natural reserve, Sultanate of Oman. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

Fig. 4. Arabian gazelle (Gazella arabica) held in captivity at Al Wusta natural reserve, Sultanate of Oman. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

Fig. 5. Sandy gazelle (Gazella marica) at Al Wusta natural reserve, Sultanate of Oman. Over 1,150 gazelles are held in the reserve. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

Fig. 6. Female green turtle (Chelonia mydas) measured by a ranger of the Environment Authority at Ras Al Hadd, Sultanate of Oman. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

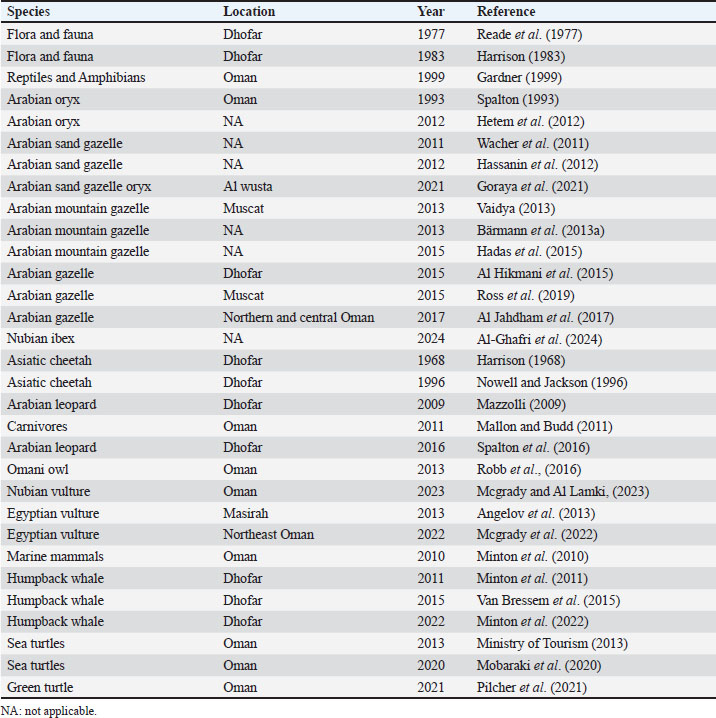

Fig. 7. Freshly born green turtles collected by rangers at Ras Al Hadd turtle natural reserve. (Photo by M. Giangaspero). In some cases, satellite devices have been placed on the shell of some females in the framework of pilot projects. With this equipment, one turtle could be recognized to be returned after 31 years. However, the staff is generally excluded from the follow-up of satellite monitoring. Partially, the beaches are protected by a 50 cm high wall to prevent young and adult turtles from moving in the wrong direction toward interior lands instead of reaching the waters. During the hatching period, juveniles moving inland are collected by rangers and released at the shore. In one night, over 2,000 new born turtles may be assisted (Fig. 7). In addition to the abovementioned reserves and sanctuaries, other relevant protected areas in the country are the Al Jabal Al Akhdhar natural landscape reserve, the Qurm nature reserve, the Al Saleel nature reserve, and the Khor Taqah Sanctuary. The Office for Conservation of the Environment of the Diwan of the Royal Court formerly administrated the management of the wild fauna patrimony. Recently, the Agency for the Environment, established in 2020, replaced the Diwan’s role and fully took responsibility for protecting wild fauna, particularly endangered vulnerable species. Therefore, the centers and reserves now fall under his competence. The Environment Authority’s responsibilities include developing plans and programs to protect and manage the environment and wildlife, preserving natural resources and the various environmental systems, developing scientific research, spreading awareness, and developing projects to return the Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) to its natural habitats. In this direction, in November 2024, the WWR team planned to release some numbers of oryx and Reem gazelles to the wild in different locations in: the southern part of the desert, a place called Maqshan, near the city of Thamriate (after Hima); Br Al Hakman (about 400 km from the Oryx Sanctuary); and the northern part at Wahiba sands. The Authority is also tasked with issuing and implementing environmental laws and legislation as required by the environmental interest and undertaking environmental control and inspection. The most important and recent step for the strengthening of efforts on conservation is represented by Oman’s vision for the future, “Oman 2040.” Developed in 2019, in line with the Royal Directives of His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said, it is a 20-year nationwide multisector document, providing guide and key reference for planning activities. Vision 2040 defined the national priorities to be achieved and strategic directions to be followed. Environment and natural resources were selected along with the other priorities, toward effective, balanced, and resilient ecosystems to protect the environment and ensure sustainability of natural resources to support the national economy. From a baseline rank of 116th country, out of 127, in 2018, the plan is particularly ambitious aiming to achieve a 2030 target by improving up to the top 40 countries and finally to reach a 2040 target becoming Oman part of the top 20 countries, according to their environmental performance indicators. Concerning research history, a number of studies have been conducted to investigate and provide accounts of the environment, ecology, meteorology, wild fauna, and vegetation of the Sultanate. Some studies were general. In 1977, the Ministry of National Heritage and Culture undertook a scientific survey on the flora and fauna present in Dhofar. Reports concerned 17 groups of plants and animals. Of relevance to agricultural entomology, species of Acridoidea of eastern Arabia, the Rhopalocera of Dhofar, the larger Heterocera, sphecid wasps of Oman, and Bombyliidae of Oman were considered. Of relevance to medical and veterinary entomology, reports were prepared on Lepidoptera, scorpions, and ticks (Reade et al., 1977). Another general study was conducted on the reptiles and amphibians of Oman (Gardner, 1999). Other studies were focused to specific animal species. Some concerned wild carnivores, in particular the Arabian leopard (Harrison, 1968; Nowell and Jackson, 1996; Mazzolli, 2009; Mallon and Budd, 2011; Spalton et al., 2016) and others wild ruminants, as the Arabian oryx and gazelles (Spalton, 1993; Wacher et al., 2011; Hassanin et al., 2012; Hetem et al., 2012; Bärmann et al., 2013a, b; Vaidya, 2013; Al Hikmani et al., 2015; Hadas et al., 2015; Al Jahdham et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2019; Goraya et al., 2021). Marine mammals (Minton et al., 2010, 2011; Van Bressem et al., 2015; Minton et al., 2022), sea turtles, in particular the green turtles, (Ministry of Tourism, 2013; Mobaraki et al., 2020; Pilcher et al., 2021), and avian species such as the Omani owl and Egyptian and Nubian vultures (Angelov et al., 2013; Robb et al., 2016; Mcgrady et al., 2022; Mcgrady and Al Lamki, 2023) were also studied. Recently, newly developed investigation technologies, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms, have also been considered for accurate genotyping in the framework of conservation programs for the threatened Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana) in Oman (Al Ghafri et al., 2024). A list of scientific studies on wild fauna in Oman is presented in Table 1. Current Status of Wildlife in OmanDesert and oryx and gazellesThe climate greatly influences the wild fauna, and only highly resistant animal species are adapted to survive in this environment. The abundance that attracts many living beings to the Sea of Arabia contrasts greatly with the desert landscape. In the immensity of the stony desert Jiddat Al Harasis, in south-central Oman, separating northern Oman from Dhofar, there are no water springs, and temperatures may easily overcome 40°C; therefore, survival is almost impossible. However, in spring, coastal dew meets plants, and their fresh sprouts constitute the preferred feed of the Arabian oryx or white oryx (Oryx leucoryx). In the past, large herds grazed the deserts of Arabia. Nowadays, according to IUCN (2017d), only a few individuals of these species threatened with extinction are in the wild, and about 6,000 live in sanctuaries (2017d). There exist five species of oryx: the scimitar-horned oryx or Libyan oryx, Oryx dammah (Cretzschmar, 1827), the East African oryx, Oryx beisa (Rüppell, 1835), the fringed-eared oryx, Oryx beisa callotis (Thomas, 1892), and the Gemsbok, Oryx gazella (Linnaeus, 1758), in addition to the O. leucoryx. The Arabian species lives in the most hostile conditions but is perfectly adapted to this dry and arid environment. The Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) is the smallest species of oryx. Its white hair refreshes from the sun’s rays and heat. Perfectly adapted to extreme conditions, it can partially cool its brain, and its body temperature can rise to 45°C without suffering (Hetem et al., 2012). The oryx perspires very little and does not lose moisture. Despite the perfect adaptation of this majestic animal, this did not prevent it from disappearing from the desert a few decades ago, mainly due to uncontrolled poaching. The last wild Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx) was hunted 50 years ago (Spalton, 1993). New individuals could be bred thanks to some specimens in American zoos. Ten years after the death of the last oryx in Oman, the first animals born in zoos could be reintroduced. In a few years, the herd has developed over 900 individuals at the Oryx sanctuary in Al Wusta governorate (central Oman) (data not published). Table 1. List of studies conducted on wildlife in the Sultanate of Oman.

In Oman, the Arabian sand gazelle (Gazella marica), the Arabian gazelle (Gazella arabica), and the Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana) are the predominant wild ruminant ungulates. The Arabian sand gazelle (Gazella marica) is a species native to the Middle East, specifically the Arabian and Syrian Deserts. Today, present in the Arabian Peninsula, it survives in the wild in small, isolated populations in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Yemen, and south-eastern Turkey. Small numbers may also be present in Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, and Syria (Mallon and Kingswood, 2001). In the wild, the total population of mature individuals of wild sand gazelles is thought to be 2,150, thus considered vulnerable (IUCN, 2017b). Significantly, more are held in captivity (reserves or breeding programs), such as the Yalooni breeding center or the Oryx Sanctuary, in Oman, or especially in Abu Dhabi, probably more than 100,000, are under some form of management (IUCN, 2017b). Previously, the sand gazelle was allocated as a subspecies of the goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa), indicated as Gazella subgutturosa marica. In 2010, genetic analyses revealed the real taxonomic status of the species as a distinct lineage (Wacher et al., 2011), and it is now considered a separate species. Therefore, the Arabian sand gazelle must be distinguished from the G. subgutturosa present in Israel, Jordania, east Caucasus, Iran, Gobi Desert in Mongolia, and Kazakhstan. In 2012, additional investigations demonstrated the close genetic relationship of the sand gazelle with the North African gazelle species Cuvier’s gazelle (Gazella cuvieri) and the rhim (Gazella leptoceros), suggesting that they may constitute a single species (Hassanin et al., 2012). As the sand gazelle, both are also at risk species, endangered and vulnerable, respectively (IUCN, 2017b). Another gazelle species of interest in Oman is the Arabian gazelle (Gazella arabica) (synonyms Antilope arabica, Lichtenstein, 1827; Gazella gazella ssp. Acaciae, Mendelssohn, Groves and Shalmon, 1997; or G. gazella ssp. Cora, Hamilton Smith, 1827) (IUCN, 2017a), a vulnerable species of gazelle from the Arabian Peninsula. Previously known as the Mountain Gazelle (Gazella gazella), the species was recently split into two genetically distinct lineages (G. arabica and G. gazella) (Bärmann et al., 2013a,b; Hadas et al., 2015). The Arabian lineage of the mountain gazelle inhabits lands South of the Levant, through Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, with a decreasing number of mature individuals currently estimated as 5,000–7,000 (IUCN, 2017a). In contrast, the other lineage, the Mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella), also called the Palestine Mountain gazelle, is endangered and restricted in Israel, Palestine, and the Golan Heights but is also found in parts of Jordan and Turkey, with about 2,500 individuals remaining in the wild (IUCN, 2017c). In Oman, the estimation of wildlife population is an object of various studies and is still a matter of research. For example, the estimated population densities of the Arabian gazelle (Gazella arabica) varied in the different areas of the country. In Dhofar, population densities were found to be 0.33 animals/km2 at Jabal Samhan and 0.28 animals/km2 in Nejd (total population size of 1,737 animals) (Al Hikmani et al., 2015). In northern and central Oman, in two protected areas, the estimated gazelle density was 0.161 gazelles/km2 (498 gazelles) in WWR and 25.8 gazelles/km2 (505 gazelles) in Ras Ash Shajar Nature Reserve (RSNR). The density of Arabian gazelle in RSNR was the highest recorded for a wild population (Al Jahdham et al., 2017). In other areas, the population declined, as in As Saleel Natural Park, from 1,198 ± 224 in 2,014 to 748 ± 147 in 2015 (Ross et al., 2019). Despite several field observations, no data are available for the Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana). However, it is considered that Oman’s Dhofar mountains are home to Oman’s largest population of Nubian ibex. Wild carnivoresAmong wild carnivores, very rare species such as the Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr) and Blanford’s fox ( Vulpes cana, Blanford, 1877) are present only in Dhofar. More distributed species, such as the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena), the Arabian wolf (Canis lupus arabs), the smallest species of wolf, the Arabian caracal (Caracal caracal schmitzi) (the lynx of the desert), the Arabian wildcat ( Felis silvestris gordoni, Forster, 1780), and the honey badger (Mellivora capensis) inhabit the country. Concerning the Arabian leopard, which has been classified as “critically endangered” since 2008 (Stein et al., 2020), it is supposed that only 200 individuals still live in the wild in the mountains of Oman, Yemen, and maybe in southern Saudi Arabia. In Oman, the Arabian leopard thrives in the Dhofar mountains, particularly in Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve. While, in Saudi Arabia are organized important activities for the reintroduction of the predator, planned for 2030 and supported by the Saudi Royal Commission for AlUla, but leopards are only captive, Oman is the only country where a project is dedicated to the Arabian leopard since 1970, still ongoing and monitoring 35 to 50 animals in the wild (CNN, 2022). Most of the observations occur in the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, the biggest protected area in Oman with 4,500 km2, in the Mirbat area, and also near the border with Yemen, in the area of Al Kharifut, between Rakhyut and Dhalkut, where animals may move between the two countries. The breeding season goes from March until August. Females give birth to one or two cubs, but only one survives (Mazzolli, 2009). In October 2023, camera traps positioned by the Environmental Conservation Office in Dhofar could document three adult Arabian leopards together. This is an exceptional circumstance for this solitary carnivore. Hypothetically, after two consecutive years of particularly pluvious monsoon seasons, rock hyrax ( Procavia capensis, Pallas, 1766), primary Arabian leopard’s prey (Spalton et al., 2016), could reproduce significantly, thus supporting the survival of multiple births of leopard cubs. In contrast to Yemen, where the leopard population is under pressure and animals may be killed, in Oman, strict protection law is applied, and killing leopards is punished with 5 years’ imprisonment. In addition, awareness on the importance of wildlife preservation is diffused among people, and farmers receive compensation from the State if attacks on domestic animals occur (a compensation program launched by the Government, in 2014). Nevertheless, it is not possible to exclude some acts of poaching related to the illegal collection of frankincense in remote areas close to the border with Yemen. Historically, in the past, another emblematic species of predatory mammal, the lion (Panthera leo persica), was an important part of the Arabian landscape, as demonstrated by Neolithic rock engravings of lions in Saudi Arabia and Oman (Mallon and Budd, 2011). The lion began to disappear from the Arabian Peninsula and, the timing of the extinction may have been the 12-13th centuries. However, it still remains in the collective consciousness and memory of the inhabitants of the region (Ghai, 2023). In more recent times, the Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), currently only surviving in Iran, used to occur also in the northern and southeastern fringes of the Arabian Peninsula (Harrison, 1968). In Yemen, the last known cheetah was sighted in Wadi Mitan in 1963, near the border with Oman, and it had been reported in both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait before 1974 (Nowell and Jackson, 1996). The Asiatic cheetah used to occur also in Oman’s Dhofar mountains. Oman’s last known cheetah was killed near Jibjat in 1977 (Harrison, 1983). Since predatory mammals are of wide international interest and are among the umbrella and apex species for ecosystems, they attract the attention of the wider public and researchers. As in the case of the leopard, their occurrence was the basis for designating protected areas, in Oman and elsewhere, which were also reserves for the entire spectrum of species. However, information about these species from the Arabian Peninsula still remains very scarce and each additional study constitutes an important source of knowledge. Rare birdsThe Egyptian vulture ( Neophron percnopterus, Linnaeus, 1758), the golden eagle ( Aquila chrysaetos, Linnaeus, 1758), and the Omani owl (only discovered in 2013 and named Strix butleri, Hume, 1878) (Robb et al., 2016) are present in Oman. This Arab country is important for native and migratory species because its strategic position among three continents and makes the Sultanate an important stage for many migratory birds. Barr Al Hikman, located in the center of Oman’s east coast in Al Wusta Governorate (the central region), is one of the most important stops on the Arabian Peninsula with a permanent wetland. This area is considered one of Oman and Southeast Asia’s most important bird migration stations. Many birds congregate here, especially water birds coming from as far as Siberia’s northern shores. Over 500,000 birds transit between summer spawning grounds and winter-feeding areas. Sixty-three species of waterfowl have been recorded in this coastal wetland. It is also a breeding area for 40,000 pink flamingos ( Phoenicopterus roseus, Pallas, 1811) (Times of Oman, 2017; Observer, 2021). Oman is a stronghold for several species of vultures. The Lappet-faced vultures or Nubian vultures ( Torgos tracheliotos, Forster, 1791) are the largest breeding birds in Oman (wingspan 2.8 m, weight 6–8 kg) (Mcgrady and Al Lamki, 2023). According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the Nubian vultures are designated as globally endangered, with an estimated world population of under 6,500 individuals (IUCN, 2021). In Oman, it is sheltered the most important resident population of the Arabian Peninsula of Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus), with numbers often reaching hundreds of birds in a single location, and it is also a crucial wintering area for a very large number of Egyptian vultures migrating from Eastern Europe (Angelov et al., 2020). Egyptian vultures, also called the white scavenger vulture or pharaoh’s chicken, are threatened worldwide. Mountains are optimal for the three months at nest required for juveniles before reaching autonomy. Most of the vultures spend their days mostly in northeast Oman in the Hajar mountains (Mcgrady et al., 2022). Furthermore, the island of Masirah is also an optimal breeding site for the Egyptian vulture. On the island, they were observed 53 breeding pairs and estimated there to be 65–80 territories, corresponding to the second densest population in the world, next to Socotra Island, Yemen (Angelov et al., 2013). Such a favorable environment suggested projects of relocation and release in Oman of rescued vultures from other countries, as in 2017 from Bahrain, providing them with the best chance of reintegration into a natural environment. Sea wildlife and turtlesThe arid hinterland contrasts with the richness of the coast. The north of the Sultanate is limited by the Gulf of Oman, a true accelerator of nature. It is one of the world’s most productive stretches of water, with incredible marine biodiversity. The secret of this abundance lies in the depth and, more precisely, in its water, which is rich in nutrients. Sunlight activates the growth of plankton, creating the basis for feeding marine fauna. No link in the food chain lacks food, even the most impressive shark in the world, the whale shark ( Rhincodon typus, Smith, 1828). Once a year, hundreds of juveniles leave the Persian Gulf to reach the Indian Ocean, crossing the Gulf of Oman for a few weeks, feeding not only on plankton and krill but also on prey of more than 2 mm, such as fish eggs, crustacean larvae, or tiny jellyfish. More than 100 individuals can be observed at once. This may become rare because these giants are endangered. Risso’s dolphin ( Grampus griseus, Cuvier, 1812), long-finned pilot whale ( Globicephala melas, Traill, 1809), large dolphins of the Indian Ocean, as the Humpback dolphins (Sousa plumbea) of the genus Sousa (Gray, 1866), with groups of up to 30–50 individuals, inhabit the Omani sea (Minton et al., 2010). In addition, the common dolphin ( Delphinus delphis, Linnaeus, 1758) is observable in immense groups that swim up to 60 km/hour. It is also present the Bryde’s whale ( Balaenoptera edeni, Anderson, 1879), also named “tropical” for her preference for warm waters, the less studied whalebone species. In the Ocean, the humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), present in the Dhofar’s waters, and the green turtles (Chelonia mydas) are the main important marine species present in the Omani sea. The humpback whale of the Arabian Sea has a population of less than 100 individuals living in Oman (Minton et al., 2011). Marine mammals of 20 m and 50 t have a unique feature: they are sedentary. Unlike other species, they do not migrate between northern feeding areas and southern breeding sites (Minton et al., 2011). The Oman coast offers everything they need to live and welcome their offspring: shallow, cozy waters, and abundant food. Appearing for over 70,000 years and genetically isolated off Oman (Pomilla et al., 2014), they have developed unique songs (Minton et al., 2011). They often show areas of depigmentation because they are vulnerable to a poxviral dermatopathy (Van Bressem et al., 2015, 2022; Minton et al., 2022) that marks the skin and signs of stress. They are particularly fragile due to intra-species reproduction and exposure to the perturbing aspects of human activity (noise of boat’s engines disrupting their communications, dangerous propellers, and nets). It is undoubtedly one of the rarest whale species in the world. The sea of Oman is an immense reserve of turtles. Very ancient inhabitants of the sea, their prehistoric ancestors already lived on earth more than 200 million years ago (Lyson et al., 2013). They nourish algae and aquatic plants, crustaceans, shells, worms, and jellyfish. Adults are vegetarian thanks to bacteria in their digestive system that make non-edible plant cells available for other species (Bjorndal, 1982; Ross, 1985). Out of the world’s seven species of sea turtles, five can be found in the Sea of Oman (Ministry of Tourism, 2013; Mobaraki et al., 2020). In addition to the green turtles, other turtles of the Cheloniidae family (Oppel, 1811) nest in Oman. The loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta gigas) of the Pacific Ocean, different from the subspecies of the Atlantic Ocean (Caretta caretta caretta), both belonging to the species Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758), nests on Masirah Island, the shores of Dhofar and Daymaniyat Islands. The hawksbill turtle ( Eretmochelys imbricata, Linnaeus, 1766) lives all its life in the waters of Oman. It can be observed on the shores of Muscat and in the archipelago Daymaniyat, where it lays its eggs for 2 months. Based on the observations made by the rangers of the Environment Authority, the deposition can last up to 3 hours. Females reach the shore even three or four times, laying about 100 eggs per nest, up to 300 in some years. The olive ridley turtle ( Lepidochelys olivacea, Eschscholtz, 1829), known commonly as the Pacific ridley sea turtle, nests on Masirah Island. The leatherback turtle ( Dermochelys coriacea, Vandelli, 1761), Dermochelyidae family (Fitzinger, 1843), is also found in Omani waters but does not nest in the Sultanate. The leatherback turtle is the biggest and heaviest among the Omani sea turtles, reaching lengths of up to 1.8 m and weighing 500 kg. All they have conservation concerns according to IUCN: loggerhead turtle, olive ridley turtle, and leatherback turtle are vulnerable, the green turtle is endangered, and the Hawksbill turtle is critically endangered. The population of Oman’s green turtles is one of the largest in the world. Almost all turtles living in the northern Indian Ocean come to lay on the beaches of the Sultanate, particularly on the 7 km coastline separating Ras al Hadd from Ras al Jinz. More than 20,000 female green turtles flock here yearly to reproduce (Ministry of Tourism, 2013), coming after a long journey from Africa and India. They were born here and use the Earth’s magnetic field as a compass, so they find these beaches decades after their birth. After mating, at sunset, with the temperature lowering and rising tide, they reach the shore up to four times to lay hundreds of eggs. The season starts in June and reaches its peak during July and August. In September, the deposition continues at a lower intensity, while in this month, the hatching period starts; thus, laying and births overlap (Fig. 8). The 90% of the Indian Ocean turtle population nests on the coasts of Oman (Ministry of Tourism, 2013; Pilcher et al., 2021). However, adults and newborns have to face many risks to survive. The turtles arrive to lay in the evening with the rising tide. If they do not return to the sea, they risk dehydration. The temperature rises rapidly to 40°C as the day begins, and their heavy shell, acting like an oven, will cook them alive. Two months after laying, the eggs hatch. Despite thousands of turtles coming to nest, only one in 1,000 newborn will reach adulthood (Fig. 9). Arabian red foxes ( Vulpes vulpes arabica, Thomas, 1902) await hatching. In less than an hour, a fox can decimate an entire nest, first satiating itself and then concealing the rest. Nets, boats, plastics, and the illegal turtle meat trade help to make sea turtles endangered species.

Fig. 8. Adult female green turtle (Chelonia mydas) and newly hatched turtle, at Ras Al Hadd, Sultanate of Oman. In September, laying and births overlaps. (Photo by M. Giangaspero). Threats and ChallengesPoaching is certainly the most important threat for wild fauna. In Oman, poaching not only led to the extinction of the oryx, but even hampered repopulation programs, especially during a period of heavy oryx hunting in 1996–1997. Historical photos of hunted animals clearly illustrate the problem of uncontrolled hunting in the past (Figs. 10 and 11). Despite in the country, as per Ministerial Decision, the hunting of all species of the wild is banned since 1993 (Insall, 2001), recent reports of law infringements recall attention on wildlife threatening. For example, two Arabian mountain gazelles (Gazella gazella cora) were poached in Al Saleel National Park in Al Kamil Wal Wafi area in May 2013, and in July 2013, other ten Arabian mountain gazelles have been illegally killed in the Wadi Khawan area at north-east of Muscat (Fig. 12) (Vaidya, 2013). In Oman, sharks also become victims of illegal fishing for fin collection, in relation to the high demand from oriental markets. In addition, in Indian Ocean, for whales and other marine mammals, the misuse of gill nets for tuna may results to have the largest cetacean bycatch (Anderson et al., 2020). People sensitization on the value of wildlife and the importance of natural patrimony preservation, combined with monitoring and repression of crimes against wildlife are essential elements to support conservation efforts especially for vulnerable and endangered species.

Fig. 9. Killed green turtle. Apart the destruction of entire nests by predators, mortality of juveniles is high and starts just after hatching. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

Fig. 10. Oryx’s remains found at the Arabian Oryx Reserve, Al Wusta Directorate, Sultanate of Oman, during the period of heavy oryx hunting in 1996–1997. Source: Office for conservation of environment.

Fig. 11. Rangers looking at an hunted Oryx, after chasing poachers. Arabian Oryx Reserve, Al Wusta Directorate, Sultanate of Oman, 1996. Source: Office for conservation of environment. Other threats that require effective preventive actions include the degradation of the natural environment due to human activities, such as the exploitation of natural resources, like fossil fuels as it is the case in Oman for oil and natural gas extraction, with subsequent pollution, reducing and hampering habitats where wild fauna lives, or climate changes that might alter the complex equilibrium of deserts and sea. Current Initiatives and Future ProspectsThe delicate equilibrium of wild fauna in Oman requires to be studied and supported. Two main areas of research and intervention refer to the reintroduction of the ungulates held in captivity at the Oryx Sanctuary into the natural environment, and the second field of interest is the protection and improvement of reserves dedicated to sea turtles. As demonstrated by previous surveys, the potential for a high density of wild ungulates, such as gazelles, relies on well protected and productive habitats, to avoid decline due to most likely a result of poaching and competition with domestic livestock (Al Jahdham et al., 2017). This implies the preservation of natural areas suitable to sustain wild populations or to receive animals breed in captivity for repopulation, including fighting against poaching and preventing the spread of diseases from domestic animals. For example, field observations allowed us to identify the natural habitat of the Nubian ibex in Oman, a restricted area close to the Arabian oryx sanctuary, on the mountains between Haima and Duqm in the Al Wusta governorate. Nevertheless, recent mining activities started in this area, hampering this identified precious territory. It is, therefore, important to issue specific legal provisions (in line with the empowerments of the Environment Authority) to preserve intact the ecosystem of the Nubian ibex and other wild species that existed in that particular area to avoid its disappearance. In addition, only limited information is available on diseases occurring in these species (Goraya et al., 2021). On their husbandry and management requirements (this included the consideration of green products, guaranteed against poaching and illegal trade, such as the recuperation of antlers from deceased antelopes), as well as repopulation strategy; therefore, research should be undertaken on these topics. For example, protocols for rapid release in the wild should be studied, eventually considering the constitution of animal groups after weaning, for a pre-adaptation period to natural feeding to facilitate animals ready for self-sustaining upon release, considering that captive animals are fed with forage and supplemented with concentrates and salt (Fig. 13). Similarly, studies should be conducted for the selection of areas to be repopulated and the measures to be taken to protect reintroduced animals in selected territory (water points, ranger monitoring, legal instruments). Concerning domestic animals, 70% of Omani domestic animals are present in Dhofar (Ministry of Agriculture, 2011; FAO, 2021), due to the favorable climate and availability of large pastures. The 225,000 bovines ( Bos taurus, Linnaeus, 1758) and the 187,000 dromedaries ( Camelus dromedarius , Linnaeus, 1758) constitute the majority of the zootechnic resources of the region, along with less than 100,000 goats ( Capra hircus, Linnaeus, 1758) and donkeys ( Equus asinus, Linnaeus, 1758) (data not published). No prophylactic programs are in place, and farmers are culturally averse. Pastures are freely shared by the different domestic species (Fig. 14). Therefore, due to promiscuity, no barrier exists to impede the spread of diseases among them. Also, natural reserves are used as pastures by farmers. Thus, diseases may spread indirectly from domestic animals to wild fauna. In addition, the high density of domestic animals may represent an epidemiological risk factor, facilitating the circulation of diseases. This may have an impact on animal health in the rest of the county. Even if the trade of live animals from Dhofar to other governorates might be limited, only a few animals are sufficient to introduce pathogens in hosting animal herds.

Fig. 12. Arabian mountain gazelles (Gazella gazella cora) illegally killed in the Wadi Khawan area at north-east of Muscat, in July 2013 (photo courtesy of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs, Sultanate of Oman).

Fig. 13. Daily distribution of forage and concentrate to captive animals at Al Wusta natural reserve, Sultanate of Oman. (Photo by M. Giangaspero).

Fig. 14. Pastures in Dhofar, freely shared by cows and dromedaries. (Photo by M. Giangaspero). Concerning health problems observed on green turtles, only a few observations have been made at the Ras Al Hadd and Ras Al Jinz reserves. Some parasites were found on skin and shell; severe limitation of movement was observed due to the non-functioning or deformation of flippers in some turtles and diarrhea (watery and green) associated with fatigue was also observed. Mortality in adults is ascribed to fishing activities: shocks with boats, trapping into fishing nets, especially those positioned near the shore (only one time, it has been observed by the rangers the capture of 8 young individuals of 30 cm size and two adults). In addition, landing on a rocky beach is dangerous for adult females. In young turtles, mortality is due to cats, foxes, and crabs, as observed by the rangers of the Environment Authority, in force at the Ras Al Hadd turtle station. Seagulls predate only with sufficient moonlighting, for both adults and young; a behavioral risk is represented by moving toward the interior of the land at arrival or after eggs deposition and for young at hatching due to attraction by strong white lights. Out of 200 adults arriving per night, 8–9 females proceed in the wrong direction and need assistance. Two-three staff bring the turtle to the sea. In peak period, the assistance may be required even for 20 adults daily, since much more turtles arrive, up to 600 per night. If the animal is not helped, it will die in the morning (9 am) since 3 hours are sufficient to determine severe and irreversible lesions at the level of the fat accumulated under the upper shell. If the turtle is turned belly-up, it can resist for two days. This problem can be minimized by the control of lighting and the construction of walls, which are present but do not cover the entire site. However, exceptions made to some observations, and no data, especially on mortality, are available on occurrence and causes. No samples have been collected in the past 15 years, and no veterinarians are in place, resulting in a complete lack of knowledge on pathogens affecting turtles. Concerning sea turtle risk areas, two lagoons are located near Al Ras Hadd. Turtles spend about 2 months in their calm waters. The only problem observed was the excessive colonization of the shell by algae inducing difficulties in movement. However, other areas seem problematic for turtles, as natural traps are in certain areas along the coast. At the proximity of Filim, in an area designated as a natural reserve in 2014, between Sur and Duqm, several turtle remains (skulls, shells, and bones) can be observed on the shore in a certain unusually high number. Turtles might be tricked by the tide, entering very low deep water zones and then trapped with the ebbing tide, unable to recover the sea and eventually dying from dehydration, suggesting that the area represents a natural threat to turtle survival, and corresponding to a particular topography, as revealed by satellite images (Fig. 15). Therefore, it would be worthwhile to investigate and explore the real extent of the problem and find solutions with effective measures to prevent turtle mortality. Research projects should be organized to cover the abovementioned topics, requiring dedicated human resources, equipment, and consumables for variable periods according to the complexity of planned activities and expected results. Partner institutes and authorities might be involved as necessary. For example, research institutes reference for specific diseases and the Ministry of Agriculture for matters referring to domestic animals at risk of negative influence on reintroduced wild animals. For wildlife ungulate animals, project objectives might be the review of common diseases in the captive animals at WWR, focusing on three flagship species with important conservation value: Arabian oryx, Arabian sand gazelle, and Arabian gazelle. Project activities should focus on the screening of viral, bacterial and parasitic diseases to improve the health and welfare of captive animals and study and identify best practices for preparing animals to be released in the wild to sustain an effective repopulation strategy. For turtles, project objectives might be the collection and analysis of samples to identify pathogens, toxic agents, and contaminants in sea turtle species present in the Omani waters, focusing on the green turtles, as the most abundant in the area, that might be considered bio-markers taking into account their longevity. Other project objectives might aim to improve the health and welfare of females during deposition season and young at hatching and any other turtle with health problems and ensure better protection of the reproduction sites.

Fig. 15. Satellite photo of Filim proximity, between Sur and Duqm (Google earth image V6.2.2.6613). Turtle carcasses are relatively common on the shore, suggesting that the area represents a natural threat for turtle survival. The projects should articulate from planning, management, support in preparation of legal instruments, training, clinical and surgical activities on sick and injured animals, and laboratory analysis, eventually including molecular genetic investigations to explore virus evolution in selected wildlife species. Finally, the projects should produce highly weighted papers to be published in high-impact factor international journals. However, the availability of adequate facilities will be of utmost importance. For this purpose, the projects should design and realize facilities at WWR and Ras al Hadd station for clinical therapies and surgical interventions (most of the mortality in ungulates is due to injuries) and laboratory diagnosis (room for clinical examinations and treatments, room for surgery, room for autopsies, laboratory and related equipment, and basins for rescued turtles). It is expected that such projects will provide various valuable results: the realization of facilities for clinical and surgical assistance to captive animals at WWR and to rescued marine turtles at Ras al Hadd, as well as laboratory facilities for field diagnostic activities; the obtention of data on epidemiology and etiopathogenesis of diseases affecting terrestrial and marine wild fauna; the improvement of the management of the wild fauna and their health and welfare, reducing diseases and mortality; the strengthening of feasible and sustainable repopulation strategies and protection of natural sites. ConclusionThe Sultanate of Oman is a small country with an immense biodiversity, marked by deserts, majestic mountains, and green landscapes. It is a land of contrasts, where austerity flanks abundance. It hosts the most various marine ecosystems of the region. Its coasts constitute a privileged site of nesting for marine turtles. After being considered extinct in the region, the Arabian oryx has again found its place in the desert. The Sultanate of Oman is a mosaic of unexpected landscapes, with winds that have shaped an exceptional nature, creating a complex ecosystem among the richest of the planet, which hosts the most diverse species. Each has found his place and shelter for various endangered species who live and reproduce here, such as the Egyptian vulture, the Arabian wolf, the Arabian chameleon, one of the rarest whales, the Arabian oryx, and the green turtle. Only through accurate planning and implementation of research and management of the natural resources for the preservation of the unique wild territory of Oman, the survival of these endangered wildlife will be ensured, and Oman’s Vision 2040 program target will be achieved. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Mr. Suwaibaq Humaid Al- Harsoosi and Mr. Abdullah Hamed Al- Harsoosi, Oryx Sanctuary (Al Wusta Wildlife Reserve), and Mr. Ali Salim Al-Arimi, chief of the ranger station, Ras Al Haad turtle reserve and his staff rangers Mr. Mahfooth Rashid Al-Malkhi, Mr. Hamed Ali Al-Sinadi, Mr. Hamed Khamis Al-Hikmani, Mr. Salim Abdullah Al-Wehabi, Environment Authority, Sultanate of Oman, for their excellent support and valuable discussion sharing gained experience and field observations. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. FundingThis work was not funded. Authors’ contributionsM. Giangaspero, S. Al Mahdhori, S. Al Bulushi, A.S. Bait Said, and M.K.S. Al Ghafri contributed equally to the present study. Data availabilityThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. References Al Ghafri, M.K., White, P.J., Briers, R.A., Ball, A., Senn, H., Al-Jahdhami, M.H., Al-Amri, H., Tiwari, B.B., Al-Harsusi, S.N., Al-Harsusi, A.G., Al-Rawahi, Q. and Dicks, K.L. 2024. Implications of newly developed SNPs for conservation programmes for the threatened Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana) in Oman. Conservation Genet. Resour. 16, 293–305. Al Hikmani, H., Zabanoot, S., Al Shahari, T., Zabanoot, N., Al Hikmani, K. and Spalton, A. 2015. Status of the Arabian Gazelle, Gazella arabica (Mammalia: Bovidae), in Dhofar, Oman. Zool. Middle East 61(4), 295–299. Al Jahdham, M.H., Al Bulushi, S., Al Rawahi, H., Al Fazari, W., Al Amri, A., Al Owaisi, A., Al Rubaiey S., Al Abdulasalam, Z., Al Ghafri, M., Yadav, S., Al Rahbf, S. and Ross, S. 2017. The status of Arabian Gazelles Gazella arabica (Mammalia: Cetartiodactyla: Bovidae) in Al Wusta Wildlife Reserve and Ras Ash Shajar Nature Reserve, Oman. J. Threat. Taxa. 9(7), 10369–10373. Anderson, R.C., Herrera, M., Ilangakoon, A.D., Koya, K.M., Moazzam, M., Mustika, P.L. and Sutaria, D.N. 2020. Cetacean bycatch in Indian Ocean tuna gillnet fisheries. Endangered Species Res. 41, 39–53. Angelov, I., Bougain, C., Schulze, M., Al Sariri, T., McGrady, M. and Meyburg, B.U. 2020. A globally-important stronghold in Oman for a resident population of the endangered Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus. Ardea 108, 73–82. Angelov, I., Yotsova, T., Sarrouf, M. and McGrady, M.J. 2013. Large increase of the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus population on Masirah Island, Oman. Sandgrouse 34, 140–152. Bärmann, E.V., Börner, S., Erpenbeck, D., Rössner, G.E., Hebel, C. and Wörheide, G. 2013a. The curious case of Gazella arabica. Mamm. Biol. 78 (3), 220–225. Bärmann, E.V., Wronski, T., Lerp, H., Azanza, B., Börner, S., Erpenbeck, D., Rössner, G. E. and Wörheide, G. 2013b. A morphometric and genetic framework for the genus Gazella de Blainville, 1816 (Ruminantia: Bovidae) with special focus on Arabian and Levantine mountain gazelles. Zool. J. Linnean Soc. 169, 673–696. Bjorndal, K.A. 1982. Biology and conservation of Sea Turtles. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Sea Turtle Conservation held in Washington, USA in 1979, K.A. Bjorndal (Editor) Smithsonian Institution, Cambridge, United Kingdom. CNN. 2022. The world’s smallest leopard is clinging to life in the mountains of Oman. CNN World. Available via https://edition.cnn.com/2022/01/19/middleeast/arabian-leopards-oman-conservation-spc-intl/index.html Coleman, M.A., Reddy, M., Nimbs, M.J., Marshell, A., Al-Ghassani, S.A., Bolton, J.J., Jupp, B.P. and De Clerck, O. 2022. Loss of a globally unique kelp forest from Oman. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 5020. Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2014. 5th National Report. Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs, Sultanate of Oman. Available via https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/om/om-nr-05-en.pdf Dobbs, K. 2007. Marine turtle and dugong habitats in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park used to implement biophysical operational principles for the representative areas program. Townsville, Australia: Great Barrier Marine Park Authority. FAO. 2021. Crops and livestock products: Oman. FAO STAT. Rome, Italy. Available via https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL Gardner, A.S. 1999. The reptiles and amphibians of Oman: herpetological history and current status. In The natural history of Oman: a festschrift for Michael Gallagher. Eds., Fisher, M., Ghazanfar, S. and Spalton, A. Leiden, The Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers. Ghai, R. 2023. World Lion Day 2023: the big cat once roamed Arabia and left an indelible mark on Arab culture. New Delhi, India: Down to Hearth, Wildlife & Biodiversity. Goraya, K., Al Rawahi, Q., Al Balushi, S., Al Saadi, H., Al Rahbi, S., Al Alawi, Z., Hussain, M.H. and Hussain, M. 2021. Postmortem findings in captive sand Gazelle and Arabian Oryx at Al-Wusta Wildlife Reserve, Oman. Pak. J. Zool. 53(4), 1583–1586. Gulf News. 2023. Watch videos: tropical cyclone ‘Tej’ downgraded to category 1, to further weaken, Oman says. Available via https://gulfnews.com/ Hadas, L., Hermon, D., Boldo, A., Arieli, G., Gafny, R., King, R. and Bar-Gal, G.K. 2015. Wild gazelles of the Southern Levant: genetic profiling defines new conservation priorities. PLoS One 10(3), 1–18. Harrison, D.L. 1968. Genus Acinonyx Brookes, 1828. The mammals of Arabia. Volume II: carnivora, Artiodactyla, Hyracoidea. London, UK: Ernest Benn Limited, Pp: 308–313. Harrison, D.L. 1983. The mammal fauna of Oman with special reference to conservation and the Oman Flora and Fauna Survey. J. Oman Studies 6(2), 329–339. Hassanin, A., Delsuc, F., Ropiquet, A., Hammer, C., Jansen van Vuuren, B., Matthee, C., Ruiz-Garcia, M., Catzeflis, F. and Areskoug, V. 2012. Pattern and timing of diversification of Cetartiodactyla (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria), as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes. C. R. Biol. 335(1), 32–50. Hetem, R.S., Strauss, W.M., Ick, L.G., Maloney, S.K., Meyer, L.C.R., Fuller, A., Shobrak, M. and Mitchell, D. 2012. Selective brain cooling in Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx): a physiological mechanism for coping with aridity? J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3917–3924. Insall, D.H. 2001. Oman. In Antelopes: North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Global survey and regional action plans. Eds. Mallon, D.P. and Kingswood, S.C. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. IUCN 2017a. Gazella arabica. IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2022-2. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. IUCN 2017b. Gazella marica. SSC Antelope Specialist Group. IUCN red list of threatened species. e.T8977A50187738. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. IUCN 2017c. Gazella gazella. SSC Antelope Specialist Group. IUCN red list of threatened species. e.T8989A50186574. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. IUCN 2017d. Oryx leucoryx. SSC Antelope Specialist Group. IUCN red list of threatened species. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T15569A50191626.en IUCN 2021. “Torgos tracheliotos”. BirdLife International, IUCN red list of threatened species. e.T22695238A205352949. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Kampf, J. and Chapman, P. 2016. Upwelling systems of the world. A scientific journey to the most productive marine ecosystems. Berlin, Germany: Springer International Publishing Switzerland. Lyson, T.R., Bever, G.S., Scheyer, T.M., Hsiang, A.Y. and Gauthier, J.A. 2013. Evolutionary origin of the turtle shell. Curr. Biol. 23, 1113–1119. Mallon, D. and Budd, K. 2011. Regional red list status of carnivores in the Arabian Peninsula. Cambridge, UK and Gland Switzerland: IUCN, and Sharjah, UAE: Environment and Protected Areas Authority vi+49pp. Mallon, D.P. and Kingswood, S.C. 2001. Antilopes—enquête mondiale et plans d’action régionaux, Partie 4: Afrique du Nord, Moyen-Orient et Asie. Cartes de distribution. Gland, Switzerland: UICN, p: 260. Mazzolli, M. 2009. Arabian leopard, Panthera pardus nimr, status and habitat assessment in northwest Dhofar, Oman: (Mammalia: Felidae). Zool. Middle East 47, 3–11. Mcgrady, M. and Al Lamki, F. 2023. Lappet-faced vultures in Oman. London, UK: The British Omani Society. Available via www.britishomani.org Mcgrady, M., Schmidt, M., Elahi Rad, Z. and Meyburg, B. 2022. Tracking of an Egyptian vulture Neophron percnopterus as it transitions from being a floater to a territory-holder. Sandgrouse 44, 122–133. Ministry of Agriculture 2011. Agriculture and livestock research—five-year research strategy 2011–2015. Directorate general of agriculture and livestock research. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Agriculture. p: 52. Ministry of Tourism. 2013. Turtle watching in Oman. Available via www.tourismoman.com.au Minton, G., Collins, T.J.Q., Findlay, K.P. and Baldwin, R. 2010. Cetacean distribution in the coastal waters of the Sultanate of Oman. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 11, 301–313. Minton, G., Collins, T.J.Q., Findlay, K.P., Ersts, P.J., Rosenbaum, H.C., Berggren, P. and Baldwin, R.M. 2011. Seasonal distribution, abundance, habitat use and population identity of humpback whales in Oman. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 3, 185–198. Minton, G., Van Bressem, M.F., Willson, A., Collins, T., Al Harthi, S., Sarrouf Willson, M., Baldwin, R., Leslie, M. and Waerebeek, K. 2022. Visual health assessment and evaluation of anthropogenic threats to Arabian Sea Humpback Whales in Oman. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 23(1), 59–57. Mobaraki, A., Pouyani, E.R., Kami, H.G. and Khorasani, N. 2020. Population study of foraging Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the Northern Persian Gulf and Oman Sea, Iran. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 39, 101433. Nowell, K. and Jackson, P. 1996. Asiatic cheetah. Wild cats: status survey and conservation action plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, pp: 41–44. Observer. 2021. 70 sites in Oman ideal of bird migration. Observer web team. Available via https://www.omanobserver.om/article/1108768/oman/environment/70-sites-in-oman-ideal-of-bird-migration Patzelt, A. 2015. Synopsis of the flora and vegetation of Oman, with special emphasis on patterns of plant endemism. B. W. G. 282–317. Pilcher, N.J., Antonopoulou, M.A., Rodriguez-Zarate, C.J., Jimena, C., Mateos-Molina, D., Das, H.S., Bugla, I. and Al Ghais, S.H. 2021. Movements of green turtles from foraging areas of the United Arab Emirates: regional habitat connectivity and use of marine protected areas. Mar. Biol. 168(1), 10. Pomilla, C., Amaral, A.R., Collins, T., Minton, G., Findlay, K., Leslie, M.S., Ponnampalam, L., Baldwin, R. and Rosenbaum, H. 2014. The World’s most isolated and distinct whale population? Humpback whales of the Arabian sea. PLoS One 9, e114162. Reade, S.N.S., Sale, J.B., Gallagher, M.D. and Daly, R.H. 1977. The scientific results of the Oman flora and fauna survey 1977 (Dhofar). J. Oman Studies, No. Special Report No. 2. Biol. Conserv. 26(4), 379–380. Robb, M.S., Sangster, G., Aliabadian, M., Arnoud, D.B., Constantine, M., Irestedt, M., Khani, A., Musavi, S.B., Nunes, J.M.G., Sarrouf, W.M. and Walsh, A.J. 2016. The rediscovery of Strix butleri (Hume, 1878) in Oman and Iran, with molecular resolution of the identity of Strix omanensis Robb, van den Berg and Constantine, 2013. Avian Res. 7, 1–10. Ross, J.P. 1985. Biology of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, on an Arabian feeding ground. J. Herpetol. 19(4), 459–468. Ross, S., Al Zakwani, W.H., Al Kalbani, A.S., Al Rashdi, A., Al Shukaili, A.S. and Al Jahdhami, M.H. 2019. Combining distance sampling and resource selection functions to monitor and diagnose declining Arabian gazelle populations. J. Arid Environ. 164, 23–28. Sherif, M., Chowdhury, R. and Shetty, A. 2014. Rainfall and intensity duration frequency (IDF) curves in the United Arab Emirates. In Proceedings of the World environmental and water resources congress 2014: water without Borders ASCE, American Society of Civil Engineers, Reston, VA, USA. pp. 2316–2325. Spalton, J.A. 1993. A brief history of the reintroduction of the Arabian oryx Oryx leucoryx into Oman 1980–1992. Int. Zoo. Yearb. 32(1), 81–90. Spalton, A. and Al-Hikmani, H. 2014. The Arabian leopards of Oman. Page (Hannah Young, editor) first. Muscat, Oman: Diwan of Royal Court of the Saltanate of Oman and Stacey Publishing. Spalton, J.A., Al Hikmani, H.M., Jahdhami, M.H., Ibrahim, A.A.A., Bait Said A.S. and Willis, D. 2016. Status report for the Arabian Leopard in the Sultanate of Oman. CAT News Special Issue 1, 26–32. Stein, A.B., Athreya, V., Gerngross, P., Balme, G., Henschel, P., Karanth, U., Miquelle, D., Rostro-Garcia, S., Kamler, J.F., Laguardia, A., Khorozyan, I. and Ghoddousi, A. 2020. Panthera pardus (amended version of 2019 assessment). IUCN Red List Threatened Species 8235, e.T15954A163991139. Times of Oman. 2017. Rise in number of Juvenile Greater Flamingos at Barr Al Hikman, Oman. Times of Oman, Muscat Media Group, Times News Service. Available via https://timesofoman.com/article/31283-rise-in-number-of-juvenile-greater-flamingos-at-barr-al-hikman-oman UNESCO. 2007. Oman’s Arabian Oryx Sanctuary : first site ever to be deleted from UNESCO’s World Heritage List. Paris, France: UNESCO. Available via https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/362 UNESCO. 2022. Arabian oryx sanctuary. Paris, France: UNESCO. Available via https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/654 Van Bressem, M.F., Van Waerebeek, K. and Duignan, P.J. 2022. Tattoo skin disease in cetacea: a review, with New Cases for the Northeast Pacific. Animals 12, 3581. Wacher, T., Wronski, T., Hammond, R.L., Winney, B., Blacket, M.J., Hundertmark, K.J., Mohammed, O.B., Omer, S.A., Macasero, W., Lerp, H., Plath, M. and Bleidorn, C. 2011. Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences reveals polyphyly in the goitred gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa). Conserv. Genet. 12, 827–831. World Bank. 2021. Oman country specific information. Climate change knowledge portal. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group. Available via https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/ Vaidya, S.K. 2013. 6 suspect gazelle poachers held in Oman. Gulf News. Available via http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/oman/6-suspect-gazelle-poachers-held-in-oman-1.1204189 (Accessed 20 April 2024). Van Bressem, M.F., Minton, G., Collins, T., Willson, A., Baldwin, R. and Van Waerebeek, K. 2015. Tattoo-like skin disease in the endangered subpopulation of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, in Oman (Cetacea: Balaenopteridae). Zool. Middle East 61(1), 1–8. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Giangaspero M, Mahdhori SA, Bulushi SA, Said ASB, Ghafri MKSA. Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(1): 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 Web Style Giangaspero M, Mahdhori SA, Bulushi SA, Said ASB, Ghafri MKSA. Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=180920 [Access: January 15, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Giangaspero M, Mahdhori SA, Bulushi SA, Said ASB, Ghafri MKSA. Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(1): 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Giangaspero M, Mahdhori SA, Bulushi SA, Said ASB, Ghafri MKSA. Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 15, 2026]; 15(1): 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 Harvard Style Giangaspero, M., Mahdhori, . S. A., Bulushi, . S. A., Said, . A. S. B. & Ghafri, . M. K. S. A. (2025) Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. Open Vet. J., 15 (1), 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 Turabian Style Giangaspero, Massimo, Salah Al Mahdhori, Sultan Al Bulushi, Ali Salim Bait Said, and Metab Khalaf Salim Al Ghafri. 2025. Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (1), 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 Chicago Style Giangaspero, Massimo, Salah Al Mahdhori, Sultan Al Bulushi, Ali Salim Bait Said, and Metab Khalaf Salim Al Ghafri. "Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Giangaspero, Massimo, Salah Al Mahdhori, Sultan Al Bulushi, Ali Salim Bait Said, and Metab Khalaf Salim Al Ghafri. "Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates." Open Veterinary Journal 15.1 (2025), 35-53. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Giangaspero, M., Mahdhori, . S. A., Bulushi, . S. A., Said, . A. S. B. & Ghafri, . M. K. S. A. (2025) Wild fauna in Oman: Current situation and perspectives, with particular interest to turtles and ungulates. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (1), 35-53. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i1.4 |