| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3277-3284 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(7): 3277-3284 Research Article Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndromeYudit Oktanella1* , Muhammad Reza Fahlevi2, Handayu Untari3, Viski Fitri Hendrawan1, Nabilla Rizky Mahalita2, Jamilaturrosyidah2 and Anna Lystia Poetranto41Department of Veterinary Reproduction, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia 2Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia 3Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia 4National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Yudit Oktanella. Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia. Email: yudito [at] ub.ac.id Submitted: 27/02/2025 Revised: 12/06/2025 Accepted: 16/06/2025 Published: 31/07/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

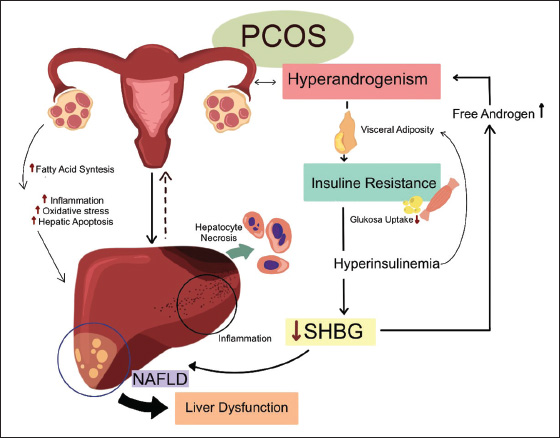

ABSTRACTBackground: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a prevalent endocrine disorder that can lead to metabolic and reproductive complications, including liver dysfunction. Despite its widespread occurrence, the mechanisms linking PCOS to hepatic impairment remain unclear, necessitating reliable animal models for further investigation. Aim: This study evaluates the impact of testosterone propionate and estradiol benzoate on liver function in a rat model of PCOS. Methods: A completely randomized design was implemented using 18 female Wistar rats divided into three groups. The control group received 0.9% NaCl orally, while group 1 received testosterone propionate (100 mg/kg body weight, intraperitoneally), and Group 2 received estradiol benzoate (2 mg/kg BW, intraperitoneally). After 28 days, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) and glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) levels were measured, and liver histopathology was assessed for hepatocyte necrosis. Results: One-way ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference in SGOT levels among groups (p < 0.05), with the lowest mean observed in the estradiol group (G2). However, the SGPT levels and histopathological scoring of hepatocyte necrosis did not significantly differ between the groups. All groups exhibited mild to moderate necrosis, which may have been influenced by environmental factors such as ammonia exposure. Conclusion: Acute induction of PCOS using testosterone propionate and estradiol benzoate resulted in modest hepatocellular changes, with only SGOT levels showing a significant group difference. These findings suggest that the hepatic response is limited under the tested conditions. Future studies should consider longer exposure durations, combined metabolic stressors, and environmental controls to better simulate PCOS-associated liver dysfunction and to develop more robust animal models for therapeutic evaluation. Keywords: Animal model, Liver, Polycystic ovary syndrome, SGPT, SGOT. IntroductionPolycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder affecting 6%–10% of women globally, with a notably high prevalence of 37.2% among Indonesian women aged 20–80 (Azziz et al., 2016). Characterized by hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction and polycystic ovarian morphology, PCOS contributes significantly to infertility and metabolic disturbances such as insulin resistance, obesity, and dyslipidemia. These metabolic issues can lead to complications like nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which is now recognized as a key component of PCOS pathology (Spremović Rađenović et al., 2022). Despite its widespread prevalence and severe health implications, PCOS is frequently underdiagnosed and poorly understood. This is particularly true in low-resource settings like Indonesia, where awareness and diagnostic infrastructure are limited (Chainani, 2019). The liver plays a central role in the metabolic disturbances associated with PCOS. It regulates glucose and lipid metabolism, detoxification, and hormone regulation, all of which are disrupted in PCOS. Elevated levels of free fatty acids, a hallmark of PCOS, contribute to hepatic steatosis and liver damage, as evidenced by increased levels of serum glutamic pruvic transaminase (SGPT) and serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) (Yao et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Histopathological changes, such as hepatocyte necrosis and inflammation, further underscore the liver vulnerability in PCOS. However, the mechanisms linking PCOS to liver dysfunction remain poorly understood, emphasizing the critical need for reliable preclinical models to study these interactions (Wang et al., 2022). The liver mechanisms related to PCOS are presented in Figure 1.

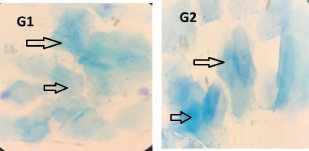

Fig. 1. Liver mechanisms play a crucial role in the metabolic disturbances associated with PCOS. Animal models, particularly rat models, are indispensable tools for investigating the pathophysiology of PCOS and its complications. They provide a controlled environment for studying the effects of hormonal imbalances, such as hyperandrogenism and hyperestrogenism, on metabolic and hepatic health. However, existing models often fail to fully replicate the complex metabolic and hepatic complications observed in humans, limiting their utility in translational research. Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between PCOS and liver damage, with patients with PCOS exhibiting elevated levels of serum transaminases, such as SGPT and SGOT, as well as histopathological changes in the liver, including hepatocyte necrosis and inflammation (Baranova et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2023). This gap underscores the need for optimized induction protocols and dosages to create more accurate and reliable animal models of PCOS that faithfully recapitulate the metabolic and hepatic complications observed in the clinical setting. The development of accurate animal models for PCOS is critical for understanding its pathophysiology and associated complications, particularly liver dysfunction. Current models often fail to replicate the full spectrum of metabolic and hepatic abnormalities observed in humans, limiting their translational relevance (Stener-Victorin et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2014). This study addresses this gap by evaluating the effects of testosterone propionate and estradiol benzoate on liver function in a rat model, offering crucial insights into the challenges of replicating PCOS-associated hepatic dysfunction in animal models. These findings underscore the need for optimized induction protocols and dosages to better mimic human PCOS pathology. By highlighting these limitations, this research offers a foundation for future studies to refine animal models, ultimately advancing our understanding of PCOS and its metabolic sequelae. Materials and MethodsThis study was an experimental laboratory research conducted in several laboratories: the Experimental Animal Laboratory at Brawijaya University for the maintenance and treatment of test animals, the Veterinary Anatomy Laboratory for necropsy and organ sampling, the Anatomical Pathology Laboratory at Brawijaya University for the preparation and examination of histopathology, and the Clinical Pathology Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Brawijaya University, for SGPT and SGOT testing. Development of a PCOS animal modelThis study employed a PCOS animal model to mimic the hormonal disturbances observed in human PCOS, including hyperandrogenism and disrupted estrous cycles. Eighteen female Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus), aged 6–8 weeks and weighing 130–180 g. The rats were acclimatized for 7 days prior to treatment, housed in standard polypropylene cages (Tecniplast, Italy) and maintained at 22°C ± 2°C with a 12:12-hour light-dark cycle. They were provided ad libitum access to food (Comfeed, Indonesia) and water. Normal control (NC) group (n=6) are normal healthy female rats without PCOS induction. Group 1 (n=6) rats received testosterone propionate (Global Anabolic, German) intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 mg/kg body weight (BW) in a volume of 0.13 ml per rat for 12 days. Group 2 (n=6) rats received estradiol benzoate (Java Animal Care, Indonesia) intraperitoneally at a dose of 2 mg/kg BW, in a volume of 0.13 ml per rat, for two consecutive days, following the protocol of Oktanella et al. (2023). Monitoring the estrous cycle was a crucial step in verifying the successful induction of PCOS because disruption of normal cycle patterns is a key indicator of the condition. Estrous cycle monitoring was performed using a vaginal swab method and examined under a light microscope (Olympus CX23, Japan), confirming persistent estrous as an indicator of PCOS induction marked by the presence of cornified epithelial cells for more than two consecutive days (Fig. 2). These findings are consistent with the hormonal imbalance and anovulatory state characteristics of PCOS, further validating the model used in this study. Serum testosterone levels were measured using a rat-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Bioenzy, Rat ELISA Kit) to confirm the induction of PCOS in the experimental rat model, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCOS group showed elevated testosterone levels, with mean concentrations of approximately 482 µg/l, indicating successful model establishment, consistent with previously reported androgen levels in PCOS-induced rats (Mannerås et al., 2007; Maliqueo et al., 2013). Sample collectionPrior to euthanasia, the animals were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine and xylazine administered at doses of 100 and 15 mg/kg BW, respectively. Once the animals were anesthetized, cervical dislocation was performed, and the rats were placed in a dorsal recumbent position on a dissection tray for the subsequent procedures. After euthanasia, blood collection was performed via the intracardiac route, and the blood was drawn and transferred into red vacutainer tubes. The tubes were then tilted to expedite serum collection. The serum samples were subsequently transferred into microtubes for biochemical testing of SGPT and SGOT levels. The abdominal cavity of the rat was then opened to collect the liver. The collected liver organs were placed in organ containers filled with 10% formalin at a ratio of 1:10 for preservation.

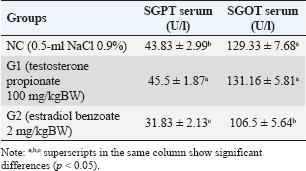

Fig. 2. Cytological examination of vaginal swab in rats. The estrous cycle phase in Groups 1 and 2 is indicated by the presence of cornified epithelial cells (black arrows). Determination of SGPT and SGOT serumThe primary reagents for the measurement of SGPT and SGOT comprised two separate components. The next step involved combining Reagent 1 for SGPT and Reagent 2 for SGPT in a 5:1 ratio. A similar mixing procedure was followed for SGOT with Reagent 1 and Reagent 2 using the same ratio. Once the reagents were prepared, a 100 µl blood sample was collected in an EDTA vacutainer and transferred into a reaction tube for analysis using a spectrophotometer. The spectrophotometer was set to a temperature of 37°C and a wavelength of 340 nm, with a measurement duration of 60 seconds and a delay time of 30 seconds, using a factor of 1,745. Subsequently, 1,000 µl of the blank solution (distilled water) was introduced into the spectrophotometer. The SGPT test was then performed by adding 1,000 µl of the homogenized sample combined with the working reagent into the spectrophotometer, and the results were recorded. The SGOT test was conducted using the same procedure, with 1,000 µl of the homogenized sample and working reagent also being placed into the spectrophotometer, and the results were duly noted. The measurement of SGPT and SGOT levels were measured following the protocol described by Kurniawati et al. 2016. Histopathological examination of the liverLiver tissue samples were processed using a tissue processor, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4-μm thickness using a rotary microtome. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and observed under a light microscope (Olympus CX23, Japan) at 400× magnification across five fields of view for each sample. The percentage of hepatocyte necrosis was assessed using a standardized scoring system (Veteläinen et al., 2006) and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, USA). For each field of view, the degree of necrosis was evaluated based on the extent of necrotic invasion, and scores were assigned according to the following criteria: Score 0: No necrosis was observed. Score 1: Mild necrosis (1%–25% of hepatocytes affected). Score 2: Moderate necrosis (26%–50% of hepatocytes affected). Score 3: Severe necrosis (51%–75% of hepatocytes affected). Score 4: Extensive necrosis (76%–100% of hepatocytes affected). This scoring system has been widely used in liver pathology studies to provide a quantitative assessment of tissue damage, enabling consistent and objective comparisons across samples (Brillant et al., 2017). Statistical analysisData were analyzed using SPSS version 25 (IBM, USA). Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was evaluated using Levene’s test. For normally distributed data with equal variances, one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test for post hoc comparisons. Histopathological scores were analyzed descriptively without statistical testing. Histological images were digitized using OlyVIA software v2.6 (Olympus, Germany) and examined using ImageJ (NIH, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SE of the mean (SEM), and significance was considered at p < 0.05. Ethical approvalThis study complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Brawijaya University (approval number 079-KEP-UB-2024). ResultsSGPT and SGOT serum in animal model of PCOSThe results of the SGPT and SGOT serum levels in each group are presented in Table 1. The average serum SGPT and SGOT levels in the experimental groups are presented in Table 1. The serum levels of SGPT and SGOT varied among the experimental groups. Rats in the G2 group showed significantly lower SGPT (31.83 ± 2.13 U/L) and SGOT (106.5 ± 5.64 U/L) levels compared to the NC and G1 groups (p < 0.05). In contrast, the G1 group showed SGPT and SGOT levels (45.5 ± 1.87 U/l and 131.16 ± 5.81 U/l, respectively) that were not significantly different from the NC group (43.83 ± 2.99 U/l and 129.33 ± 7.68 U/l, respectively) (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that PCOS induction using estradiol benzoate may have a different impact on liver enzyme activity compared with induction with testosterone propionate, potentially indicating varying degrees of metabolic disturbance or hepatocellular stress associated with the use of different hormonal treatments. Table 1. Average results of the SGPT and SGOT examinations in the PCOS model rats.

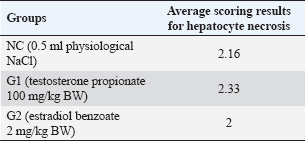

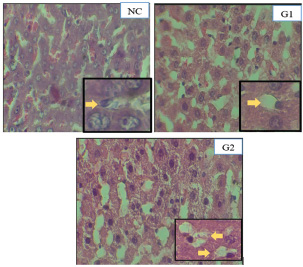

Histopathological features of an animal model of PCOSHistopathological assessment of liver tissue from the experimental groups revealed varying degrees of hepatocyte necrosis. The histopathological scoring of hepatocyte necrosis in the liver was performed using the criteria established by Veteläinen et al. 2006, which categorizes necrosis into four levels based on the percentage of necrotic cells in the observed fields. Five fields of view were examined for each sample at 400× magnification, and the average scores for hepatocyte necrosis in each group are presented in Table 2. Descriptive observations of hepatocyte necrosis scores across the three groups revealed relatively minor variations. The control group (NC), which received physiological saline, exhibited an average necrosis score of 2,16, indicating mild hepatocyte damage under normal conditions. In the group induced with testosterone propionate (G1), the average score was slightly higher (2.33), suggesting a modest increase in liver cell degeneration following androgen exposure. The estradiol benzoate group (G2) had the lowest average score of 2.00, reflecting minimal hepatocyte necrosis among the groups. Overall, all three groups fell within a narrow scoring range (2.00–2.33), implying that while there were observable differences in liver tissue response, none of the treatments appeared to induce severe hepatocellular damage. Histopathological examination of liver samples revealed notable necrotic changes across all groups, characterized by varying degrees of hepatocyte damage. Observations were conducted at 400× and 1,000× magnifications using Olivia software, focusing on five fields of view for each sample. Representative histopathological images are shown in Figure 3. Table 2. Average scoring results for hepatocyte necrosis.

Fig. 3. Histopathological features of the liver in rats stained with H&E (400×). Hepatocyte cell necrosis is indicated by yellow arrows. DiscussionPCOS is frequently associated with metabolic disturbances and liver dysfunction, including altered serum transaminase levels and hepatocyte damage. In this study, we compared two hormonal inducers—testosterone propionate and estradiol benzoate—for their effectiveness in producing metabolic alterations indicative of PCOS, using liver enzyme levels (SGPT, SGOT) and histopathological changes as markers of systemic metabolic stress. The G1 group induced with testosterone propionate had serum SGPT and SGOT levels of 45.5 ± 1.87 U/l and 131.2 ± 5.8 U/l, respectively. The SGPT value was significantly higher than that of the NC group (43.8 ± 3.0 U/l), whereas the SGOT value was not significantly different from the NC group (129.3 ± 7.7 U/l). This finding suggests that although testosterone propionate may initiate some degree of hepatic stress, it does not markedly elevate liver transaminase levels within the relatively short exposure period used in this study. A possible explanation is early-stage metabolic compensation, in which hepatocytes maintain functional enzyme regulation despite increased androgen exposure (Paixão et al., 2017). Another consideration is the duration of androgen administration, which may have been insufficient to induce severe hepatic enzyme leakage or histopathological damage in serum profiles. These findings are consistent with previous reports. For instance, a study by Ibrahim et al. (2020) demonstrated that female rats administered testosterone propionate for 21 days developed polycystic ovaries and early signs of metabolic disturbances. However, increases in liver enzymes—SGPT and SGOT—remained relatively mild and statistically insignificant compared with the control group. Likewise, Gao et al. (2022) reported that testosterone exposure over 28 days led to increased oxidative stress and disrupted lipid metabolism in rats, but significant elevations in liver transaminases were only detected after exposure periods longer than four weeks. These results support the idea that short-term androgen exposure can trigger metabolic stress without immediately causing overt hepatic injury, as reflected by serum enzyme levels. The liver may also initiate early adaptive mechanisms to manage hyperandrogenism. This includes the upregulation of endogenous antioxidant defenses, such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, or improvements in mitochondrial function that temporarily buffer hepatocytes against oxidative damage (Siemienowicz et al., 2022). A study by Zhang et al. (2021) further supported this finding, showing that low-level oxidative stress induced by exogenous testosterone increased the expression of hepatic antioxidant enzymes. This adaptive response may explain why SGOT levels remained stable in the G1 group, even when SGPT slightly increased. In contrast, the G2 group, which was induced with estradiol benzoate, showed significantly lower SGPT (31.8 ± 2.1 U/l) and SGOT (106.5 ± 5.6 U/l) levels compared with both the NC and G1 groups (p < 0.05). At first glance, this might suggest hepatoprotective effects. However, within the context of this study, these findings more likely reflect the limited capacity of estradiol benzoate to induce metabolic stress or liver-related alterations typically observed in PCOS. Rather than indicating protection, low enzyme levels may indicate incomplete PCOS induction, particularly with respect to hepatic or metabolic involvement. This suggests that estradiol benzoate may be less effective than testosterone propionate in modeling the metabolic aspects of PCOS in rats. Interestingly, although estrogen is often associated with antiinflammatory and antioxidative roles in the liver, several studies have shown that elevated or prolonged estrogen exposure can also contribute to hepatic stress or injury. For example, Xue et al. (2011) reported that chronic exposure to high levels of estradiol can increase oxidative stress and promote apoptosis in liver cells. Similarly, Czaja (2016) showed that estrogen overload may impair mitochondrial function and cause liver enzyme elevation in some pathological contexts. However, in our study, such effects were not observed—likely due to the short duration and relatively low dose of estradiol benzoate used, which may not have reached the threshold necessary to trigger hepatic injury. Moreover, a study by Goyal et al. (2010) demonstrated that although estrogen can modulate lipid metabolism and reduce fat accumulation in the liver, excessive exposure in animal models has been associated with hepatic steatosis and mild enzyme disturbances. Therefore, although estrogen’s hepatotoxic effects are possible, they appear to be dose- and duration-dependent and are not evident under the parameters used in this study. Histopathological examination revealed mild necrosis across all groups, with the highest score in G1 (2.33), followed by NC (2.16), and the lowest score in G2 (2.00). These findings suggest that testosterone propionate induces a more pronounced hepatic response, consistent with its role in inducing androgenic and metabolic stress. Testosterone increases free fatty acid flux, de novo lipogenesis, and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, producing excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) that impair hepatocyte integrity (Song and Choi, 2022; Yan et al., 2024). Histological findings further support the suitability of testosterone for inducing metabolic stress reflective of PCOS pathophysiology. In contrast, the relatively mild necrotic changes and lower enzyme levels in the G2 group suggest a weaker metabolic response, implying that estradiol benzoate may not be as effective as testosterone in generating the desired PCOS-like metabolic profile. This is crucial for selecting an appropriate hormonal agent in experimental PCOS models, especially when the goal is to study metabolic disturbances and organ-level responses, such as liver function. In G1, liver necrosis was likely exacerbated by PCOS-induced metabolic stress. Hyperandrogenism increases free fatty acid availability, thereby enhancing lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation and producing ROS. Excess ROS causes mitochondrial dysfunction, lipid peroxidation, and eventual hepatocyte necrosis (Song and Choi, 2022). The pathogenesis of hepatocyte necrosis in the PCOS model is closely linked to hyperandrogenism-induced metabolic disturbances. Excess androgen levels increase free fatty acid availability, leading to enhanced de novo lipogenesis and excessive fatty acid oxidation in hepatocyte mitochondria. Prolonged oxidative stress leads to lipid peroxidation, resulting in hepatocyte membrane instability, cellular damage, and eventual necrosis. These findings highlight the importance of carefully selecting both the hormonal agent and exposure timeline when establishing a PCOS model, particularly when the focus includes metabolic or hepatic endpoints. Overall, these findings indicate that testosterone propionate is effective in initiating the early metabolic changes typical of PCOS, including mild liver involvement. However, a longer induction period may be required to mimic the full spectrum of hepatic and metabolic disturbances observed in clinical PCOS. For researchers aiming to evaluate liver function or metabolic comorbidities in animal models of PCOS, careful consideration of dosage and duration is essential to ensure the model closely reflects the human condition. Future research should also focus on elucidating the pathways involved in hepatocyte response to various stressors, paving the way for improved management and treatment of liver-related complications in hormonal disorders. ConclusionPCOS is frequently associated with metabolic disturbances and liver dysfunction, including altered serum transaminase levels and hepatocyte damage. In this study, we compared two hormonal inducers—testosterone propionate and estradiol benzoate—for their effectiveness in producing metabolic alterations indicative of PCOS, using liver enzyme levels (SGPT, SGOT) and histopathological changes as markers of systemic metabolic stress. In PCOS, metabolic abnormalities—particularly insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism—are known contributors to liver injury. In the present study, serum SGPT and SGOT levels varied across the experimental groups, with the estradiol benzoate-induced group (G2) showing significantly lower enzyme levels compared to both the NC and the testosterone-induced groups (G1). The G1 group induced with testosterone propionate had serum SGPT and SGOT levels of 45.5 ± 1.87 U/l and 131.2 ± 5.8 U/l, respectively. These values were not significantly different from the NC group (43.8 ± 3.0 U/l and 129.3 ± 7.7 U/l, respectively), suggesting that testosterone alone did not markedly elevate liver enzyme activity within the treatment duration. This may be due to the short exposure period or early-stage metabolic compensation, in which hepatic enzyme regulation may buffer initial insults (Paixão et al., 2017). In contrast, rats in the G2 group induced with estradiol benzoate exhibited significantly lower SGPT (31.8 ± 2.1 U/l) and SGOT (106.5 ± 5.6 U/l) levels compared with both the NC and G1 groups (p < 0.05). Although this may appear protective, in the context of this study, it is more likely that estradiol benzoate was less effective in inducing metabolic stress or liver-associated PCOS than testosterone. Lower enzyme levels may reflect incomplete induction of PCOS-like metabolic disruption, limiting its effectiveness as a metabolic PCOS model inducer. Histopathological examination revealed mild necrosis across all groups, with the highest score in G1 (2.33), followed by NC (2.16), and the lowest score in G2 (2.00). These findings suggest that testosterone propionate induces a more pronounced hepatic response, consistent with its role in inducing androgenic and metabolic stress. Testosterone increases free fatty acid flux, de novo lipogenesis, and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, producing excess ROS that impair hepatocyte integrity (Song and Choi, 2022; Yan et al., 2024). Histological findings further support the suitability of testosterone for inducing metabolic stress reflective of PCOS pathophysiology. In contrast, the relatively mild necrotic changes and lower enzyme levels in the G2 group suggest a weaker metabolic response, implying that estradiol benzoate may not be as effective as testosterone in generating the desired PCOS-like metabolic profile. This is crucial for selecting an appropriate hormonal agent in experimental PCOS models, especially when the goal is to study metabolic disturbances and organ-level responses, such as liver function. The mild necrosis observed in the NC group might be attributable to unrelated factors, such as environmental stressors, individual variability, or subclinical conditions, which should be considered when interpreting baseline pathology. In conclusion, the findings indicate that testosterone propionate is more effective than estradiol benzoate in inducing liver-associated metabolic alterations in a rat model of PCOS. The increased SGPT, SGOT, and histological liver damage in G1 compared with G2 supports the use of testosterone as a reliable inducer when studying PCOS-related metabolic disorders, including hepatic involvement. Future studies should incorporate additional metabolic markers, such as insulin resistance and lipid profiles, to comprehensively assess the systemic impact of each inducer. AcknowledgmentsThe authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by internal funding from Universitas Brawijaya for the year 2024. This support facilitated the completion of the research variables reported in this article. Conflict of interestWe declare no conflicts of interest with regard to any financial, personal, or other relationships with individuals or organizations related to the material discussed in this manuscript. FundingThe research funding was provided through an internal grant from Universitas Brawijaya. Authors’ contributionsY. Oktanella* conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the research process, and contributed to manuscript writing and revision. M. R. Fahlevi and North R. Mahalita were responsible for data collection, laboratory analysis, and initial data interpretation. H. Untari contributed to the histopathological examination and analysis, ensuring the accuracy of tissue evaluation. V. F. Hendrawan conducted statistical analysis and data visualization, assisting in the interpretation of the research findings. Jamilaturrosyidah assisted in the experiment all procedures and contributed to manuscript preparation. A. L Poetranto provided critical input in methodology development and contributed to manuscript editing and final review. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data availabilityThe data used to support the findings of the study are provided in this article, and no additional data sources are necessary. ReferencesAzziz, R., Carmina, E., Chen, Z., Dunaif, A., Laven, J.S.E., Legro, R.S., Lizneva, D., Natterson-Horowtiz, B., Teede, H. J. and Yildiz, B.O. 2016. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Rev Dis. Primers. 2, 16057. Baranova, A., Tran, T.P., Birerdinc, A. and Younossi, Z.M. 2011. Systematic review: association of polycystic ovary syndromeandh metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 33, 801–814. Brillant, A.B., Simpson, K.J. and Burt, A.D. 2017. Quantitative histopathological scoring systems for liver disease: utility and limitations. Histopathology 70(4), 602–614. Chainani, E.G. 2019. Awareness of polycystic ovarian syndrome among young women in Western India. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 8, 4716–4721. Czaja, A.J. 2016. Hepatic inflammation and progressive liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 22(45), 9550–9566. Gao, X., Zhang, X., Li, Y., Liu, Y. and Wang, J. 2022. Long-term androgen exposure promotes hepatic oxidative stress and lipid metabolism disorder in rats: implications for metabolic dysfunction in PCOS. Life Sci. 289, 120225. Goyal, H.O., Braden, T.D., Mansour, M. and Williams, C.S. 2010. Estrogen-induced hepatic dysfunction in adult male rats: a potential model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Androl. 31(2), 190–200. Ibrahim, Z.S., Eid, M.I. and El Bakry, R.H. 2020. Testosterone-induced PCOS in female rats: a comparative study of different induction periods on ovarian and metabolic profiles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27(25), 31241–31251. Kurniawati, I., Nurmasitoh, T. and Yahya, T.N. 2016. Effect of giving ethanol multistep doses to level of SGPT and SGOT in Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus). J. Kedokt. Kesehat. Indones. 7(1), 30–35. Maliqueo, M., Benrick, A. and Stener-Victorin E. 2013. Rodent models of polycystic ovary syndrome: phenotypic and molecular insights. Reproduction 146(5), R173–R187. Mannerås, L, Cajander, South, Holmäng, A., Seleskovic, Z., Lystig, T., Lönn, M. and Stener-Victorin, E. 2007. A new rat model exhibiting both ovarian and metabolic characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology 148(8), 3781–3791. Oktanella, Y., Untari, H., Wuragil, D.K., Ismiawati, H., Hasanah, N.A., Agustina, G.C. and Pratama, D.A.O. 2023. Evaluation of renal disturbance in animal models of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Vet. J. 13(8), 1003–1011. Paixão, L, Ramos, R.B., Lavarda, A., Morsh, D.M. and Spritzer, P.M. 2017. Animal models of hyperandrogenism and ovarian morphology changes as features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 15, 1–11. Siemienowicz, K.J., Filis, P., Thomas, J., Fowler, P.A., Duncan, W.C. and Rae, M.T. 2022. Hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction and risk of liver disease in an ovine model of “PCOS males”. Biomedicines 10, 1291. Song, M.J. and Choi, J.Y. 2022. Androgen dysfunction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: role of sex hormone binding globulin. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1–8. Spremović Rađenović, S., Pupovac, M., Andjić, M., Bila, J., Srećković, S., Gudović, A., Dragaš, B. and Radunović, N. 2022. Prevalence, risk factors, and pathophysiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Biomedicines 10, 131. Stener-Victorin, E., Padmanabhan, V., Walters, K.A., Campbell, R.E., Benrick, A., Giacobini, P., Dumesic, D.A. and Abbott, D.H. 2020. Animal models for understanding the etiology and pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 41, 1-39. Veteläinen, R.L., Bennink, R.J., de Bruin, K., van Vliet, A. and van Gulik, T.M. 2006. Hepatobiliary function assessed by 99mTc-mebrofenin cholescintigraphy for the evaluation of steatosis severity in a rat model. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 33, 1107–1114. Wang, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, X. and Zhao, H. 2022. Liver injury and oxidative stress in a rodent model of polycystic ovary syndrome: the role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 20(1), 112. Wang, Z., Dong, H., Yang, L, Yi, P., Wang, Q. and Huang, D. 2021. The role of FDX1 in granulosa cell of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). BMC Endocr. Disord. 21, 119. Xue, X., Zhao, Y., Zhang, W. and Zhang, Z. 2011. 17β-estradiol induces oxidative stress in liver mitochondria of male rats. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 123(1–2), 157–163. Yan, H., Wang, L., Zhang, G., Li, N., Zhao, Y., Liu, J., Jiang, M., Du, X., Zeng, Q., Xiong, D., He, L., Zhou, Z., Luo, M. and Liu, W. 2024. Oxidative stress and energy metabolism abnormalities in polycystic ovary syndrome: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Reprod. Biol. Endrocinol. 22, 159. Yao, K., Zheng, H. and Peng, H. 2023. Association between polycystic ovary syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease risk: a meta-analysis. Endokrynol. Pol. 74(5), 520–527. Yu, J., Zhai, D., Hao, L, Zhang, D., Bai, L, Cai, Z. and Yu, C. 2014. Cryptotanshinone reverses reproductive and metabolic disturbances in PCOS model rats via regulating the expression of CYP17 and AR. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2014, 670743. Zhang, J., Arshad, K., Siddique, R., Xu, H., Alshammari, A., Albekairi, N. A. and Lv, G. 2024. Phytochemicals-based investigation of the pharmacological potential of Rubia cordifolia against letrozole-induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in female adult rats: in vitro, in vivo and mechanistic approach. Heliyon 10, 1–14. Zhang, J., Zhang, Y. and Lu, Y. 2023. Hepatic steatosis in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23, 1456. Zhang, L., Chen, M., Zhao, Q. and Wang, T. 2021. Testosterone induces oxidative stress and antioxidant gene expression in the liver of female rats: a mechanistic study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 212, 105936. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Oktanella Y, Fahlevi MR, Untari H, Hendrawan VF, Mahalita NR, Jamilaturrosyidah J, Poetranto AL. Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 Web Style Oktanella Y, Fahlevi MR, Untari H, Hendrawan VF, Mahalita NR, Jamilaturrosyidah J, Poetranto AL. Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=244901 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Oktanella Y, Fahlevi MR, Untari H, Hendrawan VF, Mahalita NR, Jamilaturrosyidah J, Poetranto AL. Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Oktanella Y, Fahlevi MR, Untari H, Hendrawan VF, Mahalita NR, Jamilaturrosyidah J, Poetranto AL. Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(7): 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 Harvard Style Oktanella, Y., Fahlevi, . M. R., Untari, . H., Hendrawan, . V. F., Mahalita, . N. R., Jamilaturrosyidah, . J. & Poetranto, . A. L. (2025) Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Vet. J., 15 (7), 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 Turabian Style Oktanella, Yudit, Muhammad Reza Fahlevi, Handayu Untari, Viski Fitri Hendrawan, Nabilla Rizky Mahalita, Jamilaturrosyidah Jamilaturrosyidah, and Anna Lystia Poetranto. 2025. Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 Chicago Style Oktanella, Yudit, Muhammad Reza Fahlevi, Handayu Untari, Viski Fitri Hendrawan, Nabilla Rizky Mahalita, Jamilaturrosyidah Jamilaturrosyidah, and Anna Lystia Poetranto. "Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Oktanella, Yudit, Muhammad Reza Fahlevi, Handayu Untari, Viski Fitri Hendrawan, Nabilla Rizky Mahalita, Jamilaturrosyidah Jamilaturrosyidah, and Anna Lystia Poetranto. "Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome." Open Veterinary Journal 15.7 (2025), 3277-3284. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Oktanella, Y., Fahlevi, . M. R., Untari, . H., Hendrawan, . V. F., Mahalita, . N. R., Jamilaturrosyidah, . J. & Poetranto, . A. L. (2025) Alterations in liver enzymes and histopathological changes in an animal model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3277-3284. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.38 |