| Research Article | ||

Open Veterinary Journal, (2024), Vol. 14(1): 335–340 Original Research Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern ProvinceMohammed A. Al-Hammadi1* and Mohammed Al-Rasheed2,31Department of Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 3Avian Research Center, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding Author: Mohammed Ali Al-Hammadi. Department of Microbiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Saudi Arabia. Email: malhammadi [at] kfu.edu.sa Submitted: 01/10/2023 Accepted: 15/12/2023 Published: 31/01/2024 © 2024 Open Veterinary Journal

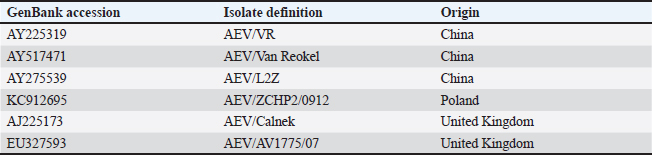

ABSTRACTBackground: A neurological infectious viral disease, avian encephalomyelitis was initially discovered in 2-week-old commercial chicks in 1930 and classified as a neurotropic viral disease. Aim: A neurological outbreak caused by avian encephalomyelitis virus (AEV) in young chicks was first reported in Al-Ahsa in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) in 2010. The aim of this article is to examine the AEV in KSA, Al-Ahsa Province. Methods: Gizzard, proventriculus, cerebrum, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata tissue samples were collected from infected chicks for histopathology test and molecular identification. Results: Infected chicks showed neurological signs particularly incoordination, mild head and neck tremors, stretching of legs, and lameness. The average morbidity and mortality rates were 35% and 10%, respectively. At necropsy, no obvious identifiable macroscopic lesions were found in the infected chicks. Nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis was found histopathologically in the central nervous system, mainly in the cerebral molecular layer. Microscopic lesions in the proventriculus showed masses of heavy numbers of small lymphocytes within the muscular layer. RT-PCR followed by sequence analysis revealed that The KSA strain (KJ939252) is intimately related to chicken European strains from Poland (KC912695) and the United Kingdom (AJ225173) with identity 99.6% than Chinese strains (AY225319, AY517471, and AY275539) with identity ranged between 94.6% and 95%. The phylogenetic tree analysis showed that the KSA strain is grouped in a similar clade with chicken European strains. Conclusion: The pattern of disease findings was typical of vertically transmitted AEV. The spread of AEV in Saudi Arabia is most likely due to the trade of birds and bird products with European countries. Keywords: Avian encephalomyelitis, Broiler chicks, Molecular identifications, Saudi Arabia. IntroductionA neurological infectious viral disease, avian encephalomyelitis (AE) was initially discovered in 14-day-old commercial chicks in 1930 and classified as a neurotropic viral disease in 1934 (Jones, 1932, 1934). AE affects young chickens, pheasants, quails, turkeys, and pigeons (Toplu and Alcigir, 2004; Calnek, 2008). Avian encephalomyelitis virus (AEV) is a nonenveloped icosahedral positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus of the Enterovirus genus in the Picornaviridae family (Shafren and Tannock, 1992; Marvil et al., 1999). AEV is composed of tetra structural proteins from the P1 region of the RNA genome (VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4) and hepta nonstructural proteins from the P2 and P3 regions (Marvil et al., 1999; Todd et al., 1999). In young chicks, clinical signs are mainly nervous, such as incoordination, paresis or paralysis, and hasty head and neck tremors, which led to the earlier identification of epidemic tremor (Markson and Blaxland, 1958; Maas and Helmboldt, 1962; Itakura and Goto, 1975; Tannock and Shafren, 1994). In layers, infection with AEV is symptomatic and does not cause neurologic signs; however, it can cause a slight decrease in the production of eggs and hatchability (Feibel et al., 1952; Taylor et al., 1955; Cheville, 1970; Calnek, 2008). AEV is spread between chickens by fecal-oral route causing enteric infection (Calnek et al., 1960); also, it can be transferred vertically from infected breeding birds to chicks via the egg, causing clinical signs upon hatching (Calnek, 2008), based on both field evidence and experimental outcomes (Van Roekel et al., 1941; Schaaf and Lamoreux, 1955; Taylor et al., 1955). The histological findings of AE are categorized into two types: first form, changes in the central nervous system (CNS) that are characterized by nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis (Itakura and Goto, 1975; Hishida et al., 1986). The second form is lesions in visceral organs, which are characterized by lymphoid aggregates (Springer and Schimittle, 1968; Butterfield et al., 1969). Lymphoid aggregates in the proventriculus are pathognomonic for AE infection, particularly when combined with central chromatolysis from CNS infections (Calnek et al., 1997). The current research aims to report the epidemiological, histopathological, and molecular identification of AEV in naturally infected young chicks in the Al-Ahsa, Eastern Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Materials and MethodsCase historyA total of 10,000 young chicks (12 days of age) in a commercial broiler farm in Al-Ahsa, KSA, were suspected of having AE disease. The mean morbidity and mortality rates were approximately 35% and 10%, correspondingly. HistopathologyTissue samples from the gizzard, proventriculus, cerebrum, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata were fixed in 10% neutral formalin and processed to paraffin wax before being cut into 4–5 μm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Bancroft et al., 1996). Nucleic acid isolationFormalin-fixed brain and proventriculus tissues were triply washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The tissue samples were grinded and suspended in PBS (10% w/v) and then disrupted by freezing and thawing three times. Filtration of samples by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm/15 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were harvested and saved at −80°C. Isolation of Viral RNA from an aliquot of the supernatant as well as from AE live virus vaccine (MERIAL) to be used as positive control using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) in accordance with the instruction manual. The RNA was eluted from the column by adding 60 μl of buffer AVE, incubating for 1 minute at room temperature, and centrifuging. RT-PCR amplificationThe VP2 gene from the AEV genome’s structural protein P1 region was amplified using the RT-PCR primers listed below: MKAE1: 5′- CTTATGCTGGCCCTGATCGT -3′ and MKAE2: 5′- TCCCAAATCCACAAACCTAGCC-3′ (Xie et al., 2005). A one-step RT-PCR kit (QIAGEN) was used for viral RNA (5 μl) reverse transcription into cDNA and cDNA amplification according to the manufacturer instructions. Sequencing and phylogenetic tree constructionThe detected AEV’s 619 bp PCR-specific band of the VP2 gene was isolated from the agarose gel, purified by the Montàge DNA gel extraction kit (Millipore, USA), and sequenced in an automated ABI 3730 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). The obtained sequence was compared to AEV sequences in GenBank using an online BLAST server (Table 1). The MEGA version 5.20 software was used for the creation of the phylogenetic tree using the Maximum Likelihood system. Table 1. AEV strains used in the assembly of a phylogenetic tree.

GenBank accession number of the sequenceThe gotten VP2 gene sequence of the determined AEV was registered in the GenBank database under accession number (KJ939252), AEV/Al-Hassa/2010/KSA. Ethical approvalThe authors affirm that this work adheres to the highest ethical standards. The authors have ensured the originality of the content, obtained necessary permissions for data and materials used, and followed ethical guidelines for research and publication. ResultsClinical findingThe infected chicks showed specific clinical signs of AEV, including depression, ataxia, mild head and neck tremors, stretching of legs, and lameness. The ataxia ranged from minor incoordination to sitting on the hocks and lateral recumbency. Necropsy and histopathologyMacroscopic examination revealed that no noticeable specific gross lesions were observed in the infected or dead chicks. Histopathology revealed that the principal changes were observed in the CNS and some viscera, particularly the proventriculus. The most prevalent form of lesion was a prominent perivascular cuffing throughout every area of the brain and spinal cord (Fig. 1a). Microgliosis occurred as diffuse and nodular aggregates. The glial lesion was primarily found in the cerebral molecular layer (Fig. 1a). Visceral lesions looked to be hyperplasia of lymphocyte masses dispersed throughout the chicks. In the proventriculus, masses of heavy numbers of tiny lymphocytes were seen within the muscular layer (Fig. 1b). RT-PCR analysisAgarose gel electrophoresis revealed that around 619 bp DNA fragments were amplified when the RNAs isolated from the brain and proventriculus tissues from infected young chicks were subjected to RT-PCR (Fig. 2, Lanes 1 and 2). Analysis of phylogenetic treeThe nucleotide sequence of the VP2 gene of the detected AEV was conducted, which allowed us to generate a phylogenetic tree to verify the origin of the Saudi Arabia AEV detected strain. The nucleotide identity of AEV/Al-Hassa/2010/KSA with the European strains isolated from Poland (AEV/Poland/KC912695) and the United Kingdom (AEV/UK/AJ225173) is 99.6% (Table 2 and Fig. 3). The phylogenetic analysis revealed that the AEV detected strain is clustered in the same clade with Poland and United Kingdom strains (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1. a- Cerebral molecular layer showing perivascular cuffing (arrow) and microgliosis. H&E ×400. b- Proventriculus showing heavy infiltration of lymphocytes within the muscular layer (arrow). H&E ×400.

Fig. 2. Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR from naturally diseased young chicks with AEV. Lane M, molecular weight PCR marker; Lane 1, brain; Lane 2, proventriculus; Lane 3, AEV vaccine kept as positive control; Lane 4, nuclease-free water kept as negative control. DiscussionAEV clinical and histological findings in naturally infected chicks were described in this study. The AEV infection was confirmed in tissue samples using RT-PCR followed by sequencing and phylogenetic tree analysis. The symptoms of tremor and incoordination observed in the infected chicks were consistent with epidemic tremor documented in AE infections (Calnek, 2008). Macroscopic examination of necropsied chicks revealed that no gross lesions were observed. CNS tumors are histopathologically consisting of a striking perivascular cuffing in all parts of the brain and spinal cord (Fig. 1a). In AEV infections (natural and experimental) of chicks, neuronal striking was viewed (Monhanty and West, 1968). In addition, according to central chromatolysis, neuronal striking is the most notable finding in experimental quail infection (Toplu, 2000). Diffuse and nodular aggregates are the result of microgliosis. The glial lesion was noticed mostly in the cerebral molecular layer (Fig. 1a). The neuronal vacuolar degeneration, mild gliosis, and perivascular lymphocytic cuffing of infrequent blood vessels were detected in AEV-infected 3-day-old pheasant chicks (Welchman et al., 2009). Visceral lesions appeared to be hyperplasia of the lymphocyte masses dispersed erratically throughout the bird. In the proventriculus, aggregates of heavy numbers of small lymphocytes were seen within the muscular layer (Fig. 1b). Lymphoid aggregates in the proventriculus are pathognomonic for AE infection, particularly when combined with central chromatolysis from CNS infections (Calnek et al., 1997). RT-PCR amplification of the VP2 gene followed by sequence analysis provides evidence of AEV infection in the young chicks in KSA; 619 bp fragments were amplified from formalin-fixed brain and proventriculus tissues collected from infected chicks (Fig. 2). Xie et al., (2005) demonstrated that RT-PCR could detect AE virus in the chicken embryo brain 3 days after inoculation. The obtained nucleotide sequence of the KSA strain (accession number; KJ939252) was examined through several alignments with six other AEV sequences available in GenBank; five from chickens and one from pheasant (Table 1). The nucleotides sequence identity of the AEV/Al-Hassa/2010/KSA (KJ939252) showed nucleotides similarities of between 94.6% and 99.6% with the chicken isolates (AY225319, AY517471, AY275539, KC912695, and AJ225173), whereas the pheasant strain (EU327593) displayed 85% with the KSA strain. The AEV/Al-Hassa/2010/KSA (KJ939252) is closely related to chicken European strains isolated from Poland (AEV/Poland/KC912695) and United Kingdom (AEV/UK/AJ225173) with identity 99.6% than Chinese strains (AEV/VR/AY225319, AEV/Van Reokel/AY517471, and AEV/L2Z/ AY275539) with identity ranged between 94.6% and 95% (Table 2 and Fig. 3). The analysis of the phylogenetic tree revealed that the KSA stain is clustered in the same clade with chicken European strains (Fig. 4). Table 2. Identity percent of the nucleotide sequence of the VP2 gene of the KSA strain compared with the available reference strains from GenBank using the ClustalW program.

Fig. 3. Nucleotide sequence alignment of about 495 bp within the VP2 gene of AEV using the ClustalW program. *The KSA strain.

Fig. 4. Phylogenetic tree of the nucleotide sequences of the VP2 gene of KSA isolate (marked with a solid triangle) and the available references strains from GenBank using maximum likelihood method with bootstrap values for n=100 replicates. ConclusionAEV was discovered as the cause of neurological disorders among young chicks in Saudi Arabia, resulting in severe economic losses for the flock. This is the first record of the detection and molecular identification of AEV in Al-Ahsa Province in Saudi Arabia. The disease most probably developed as a result of trade in poultry and poultry products with European countries. AcknowledgmentWe thank Dr Ibrahim M. El-Sabagh for his assistance in the data analysis. Also, special thanks to Dr Mahmoud M. Ismail from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Kafrelsheikh University for the valuable guidance in this study. Conflict of interestThe authors claim to have no conflicts of interest. FundingDeanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University for the financial support through Project Number (GRANT# 4758). Author contributionAll authors participated in the sample collection, laboratory analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the writing, editing, and creation of the final draft. Data availabilityAll data are provided in the manuscript. ReferencesBancroft, J.D., Stevens, A. and Turner, D.R. 1996. Theory and practice of histopathological techniques, 4th ed. New York, NY; London, UK: Churchill Livingstone. Butterfield, W.K., Helmbold, C.F. and Luginbuhl, R.E. 1969. Studies on avian encephalomyelitis IV. Early incidence and logevity of histopathology lesions in chickens. Avian. Dis. 13, 53–57. Calnek, B.W. 2008. Avian encephalomyelitis. In Diseases of poultry, 12th ed. Eds., Saif, Y.M., Fadly, A.M., Glisson, J.R., McDougald, L.R., Nolan, L.K. and Swayne, D.E. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, pp: 430–431. Calnek, B.W., Luginbuhl, R.E. and Helmboldt, C.F. 1997. Avian encephalomyelitis. In Disease of poultry, 10th ed. Eds., Calnek, B.W., Barnes, H.J., McDougald, L.L. and Saif, Y.M. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, pp: 571–581. Calnek, B.W., Taylor, P.J. and Sevoian, M. Studies on avian encephalomyelitis. IV Epizootiology. Avian. Dis. 4(4), 325–347. Cheville, N.F. 1970. The influence of thymic and bursal lymphoid systems in the pathogenesis of avian encephalomyelitis. Am. J. Pathol. 58, 105. Feibel, F., Helmboldt, C.F., and Jungherr, E.L. 1952. Avian encephalomyelitis-prevalence, pathogenicity of the virus, and breed susceptibility. Am. J. Vet. Res. 13(47), 260–266. Hishida, N., Odagiri, Y., Kotani, T. and Horiuchi, T. 1986. Morphological hanges of neurons in experimental avian encephalommyelitis. Japanese. J. Vet. Sci. 48, 169–172. Itakura, C. and Goto, M. 1975. Avian encephalomyelitis in embryos and abnormal chick on day of hatching-neurohistopathological observations. Japanese. J. Vet. Sci. 37, 21–28. Jones, E.E. 1932. An encephalomyelitis in the chicken. Science 76, 331–332. Jones, E.E. 1934. Epidemic tremor, an encephalomyelitis affecting young chickens. J. Exp. Med. 59, 781–798. Maas, H.J. and Helmboldt, C.F. 1962. Aviare encephalomyelitis. Opmerkingen over de klinische en de patho-histologishe diagnotiek. Tijdschr Diergeneesk 87, 371–397. Markson, L.M. and Blaxland J.D. 1958. Infectious avian encephalomyelitis. Vet. Rec. 20, 1208–1213. Marvil, P., Knowles, N.J., Mockett, A.P.A., Britton, P., Brown, T.D.K. and Cavanagh, D. 1999. Avian encephalomyelitis virus is a picornavirus and is most closely related to hepatitis A virus. J. General. Virol. 80, 653–662. Monhanty, G.C. and West, J.L. 1968. Pathogenesis and pathologic features of avian encephalomyelitis in chicks. Am. J. Vet. Res. 29, 2387–2400. Schaaf, K. and Lamoreux, W.F. 1955. Control of avian encephalomyelitis by vaccination. Am. J. Vet. Res. 16, 627–633. Shafren, D.R. and Tannock, G.A. 1992. Further evidence that the nucleic acid of avian encephalomyelitis virus consists of RNA. Avian. Dis. 36, 1031–1033. Springer, W.T. and Schimittle, S.C. 1968. Avian encephalomyelitis: a chronological study of the histopathogenesis in selected tissues. Avian. Dis. 12, 229–239. Tannock, G.A. and Shafren, D.R. 1994. Avian encephalomyelitis: a review. Avian. Pathol. 23, 603–620. Taylor, L.W., Lowry, D.C. and Raggi, L.G. 1955. Effects of an outbreak of avian encephalomyelitis (epidemic tremor) in a breeding flock. Poult. Sci. 34, 1036–1045. Todd, D., Weston, J.H., Mawhinney, K.A. and Laird, C. 1999. Characterization of the genome of avian encephalomyelitis virus with cloned cDNA fragments. Avian. Dis. 43(2), 219–226. Toplu, N. 2000. The use of light microscopy and fluorescent antibody technique in the diagnosis of experimental avian encephalomyelitis virus infection in chicks and quails. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Health Science, University of Ankara, Ankara, Türkiye. Toplu, N. and Alcigir, G. 2004. Avian encephalomyelitis in naturally infected pigeons in Turkey. Avian. Pathol. 33(3), 381–386. Van Roekel, H., Bullis, K.L. and Clarke, M.K. 1941. Transmission of avian encephalomyelitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 99(220), 2. Welchman, D.D.B., Cox, W.J., Gough, R.E., Wood, A.M., Smyth, V.J., Todd, D. and Spackman, D. 2009. Avian encephalomyelitis virus in reared pheasants: a case study. Avian. Pathol. 38(3), 251–256. Xie, Z., Khan, M.I., Girshick, T. and Xie, Z. 2005. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction to detect Avian encephalomyelitisvirus. Avian. Dis. 49, 227–230. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Al-hammadi MA, Al-rasheed M. Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14((1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference)): 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 Web Style Al-hammadi MA, Al-rasheed M. Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=178052 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Al-hammadi MA, Al-rasheed M. Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. Open Vet. J.. 2024; 14((1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference)): 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Al-hammadi MA, Al-rasheed M. Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. Open Vet. J.. (2024), [cited January 25, 2026]; 14((1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference)): 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 Harvard Style Al-hammadi, M. A. & Al-rasheed, . M. (2024) Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. Open Vet. J., 14 ((1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference)), 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 Turabian Style Al-hammadi, Mohammed A., and Mohammed Al-rasheed. 2024. Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. Open Veterinary Journal, 14 ((1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference)), 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 Chicago Style Al-hammadi, Mohammed A., and Mohammed Al-rasheed. "Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province." Open Veterinary Journal 14 (2024), 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Al-hammadi, Mohammed A., and Mohammed Al-rasheed. "Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province." Open Veterinary Journal 14.(1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference) (2024), 335-340. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Al-hammadi, M. A. & Al-rasheed, . M. (2024) Occurrences of avian encephalomyelitis virus in naturally infected chicks in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province. Open Veterinary Journal, 14 ((1) (Zagazig Veterinary Conference)), 335-340. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i1.30 |