| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3216-3222 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(7): 3216-3222 Research Article Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 geneJoshua I. Siner1,2, Shannon Barber-Meyer3,4, Benjamin J. Samelson-Jones1,5, Lucyan David Mech3, Valder R. Arruda1,5† and Julie M. Crudele1,5,6*1Raymond G. Perelman Center for Cellular and Molecular Therapeutics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 2Division of Hematology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, St. Louis, MO 3U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND 4Pacific Whale Foundation , Wailuku, HI 5Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 6Department of Neurology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA *Corresponding Author: Julie M. Crudele, Department of Neurology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Email: julie.crudele [at] gmail.com Submitted: 06/06/2024 Revised: 20/05/2025 Accepted: 10/06/2025 Published: 31/07/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

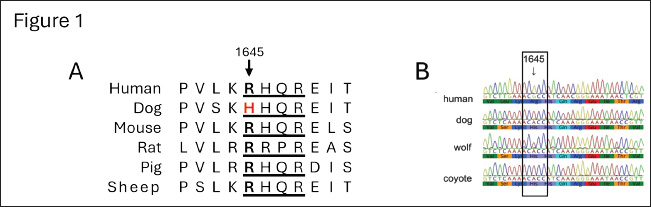

ABSTRACTBackground: Our previous characterization of canine coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) in the naturally occurring hemophilia A (HA) dog models provided insight into the evolution of the FVIII protein. We noted a unique sequence (H1645) in the R-X-X-R furin-recognition motif within the B domain of canine FVIII that was distinct from the sequence (R1645) in humans and other model organism species, including mice, rats, pigs, and sheep. R1645 was associated with lower secretion and biological activity, which can be improved with the canine H1645 sequence. Aim: Herein, we sought to determine the evolutionary origin of the canine H1645. Methods: Gray wolves (Canis lupus) are the ancestors of the domestic dogs (C. lupus familiaris). Thus, we searched for H1645 in members of the genus Canis, including the gray wolf and the closely related coyote (C. latrans), in several free-range animals from diverse geographic locations and compared it to several breeds of domestic dogs. We also compared our sequences to publicly available reference sequences for other members of the class Mammalia, order Carnivora, and suborder Caniformia. Results: 19 X chromosomes from 12 gray wolves, at least 20 X chromosomes from 14 coyotes, and at least 12 X chromosomes from 12 domestic dogs of at least 10 distinct breeds all had the canine H1645 variant. Other members of the order Carnivora and suborder Caniformia, whose sequences are publicly available, had the R1645 sequence. Conclusion: Our results suggest that the H1645 variant in the furin-consensus sequence was likely derived after the infraorders Cynoidea and Arctoidea diverged but before the separation of the gray wolf and coyote and persists through the domestic dog. Keywords: Canis, Coagulation, F8, Factor VIII, Furin. IntroductionCoagulation factor VIII (FVIII) is an essential component of mammalian hemostasis. It is derived from a single-chain polypeptide with a domain structure of A1-A2-B-A3-C1-C2 of 280 kDa consisting of a complex of two polypeptide sequences, the heavy (A1-A2-B domains) and light (A3-C1-C2 domains) chains (Gitschier et al., 1984). FVIII is proteolytically processed in the Golgi apparatus (Kaufman et al., 1988), likely by the intracellular proprotein convertase furin, which recognizes the R-X-X-R motif (Seidah and Prat, 2012), within the B-domain at positions R1313-1316 and R1645-1648 (Pittman et al., 1993; Pipe, 2009; Samelson-Jones and Arruda, 2019). Furin cleavage is important in a variety of biological processes (Seidah and Prat, 2012), including viral infectivity (Johnson et al., 2021; Hossain et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2023; Bashir et al., 2024). Interestingly, amino acid and genetic alignments of several mammals showed that canine FVIII has a unique sequence at the second presumptive furin-cleavage site (H1645) (Cameron et al., 1998), whereas porcine (Healey et al., 1996), murine (Elder et al., 1993), and ovine (Zakas et al., 2012) sequences are similar to those of humans (Gitschier et al., 1984) (R1645) (Fig. 1A). Here we explore whether the furin-cleavage site mutation in the canine FVIII was a recent modification or developed during the evolution of the genus Canis, which includes domestic dogs (C. lupus familiaris), their ancestor gray wolf (C. lupus), and the closely related coyote (C. latrans). Studying multiple animals from geographically dispersed populations of each species, particularly free-ranging gray wolves, excludes the potential admixture with dogs.

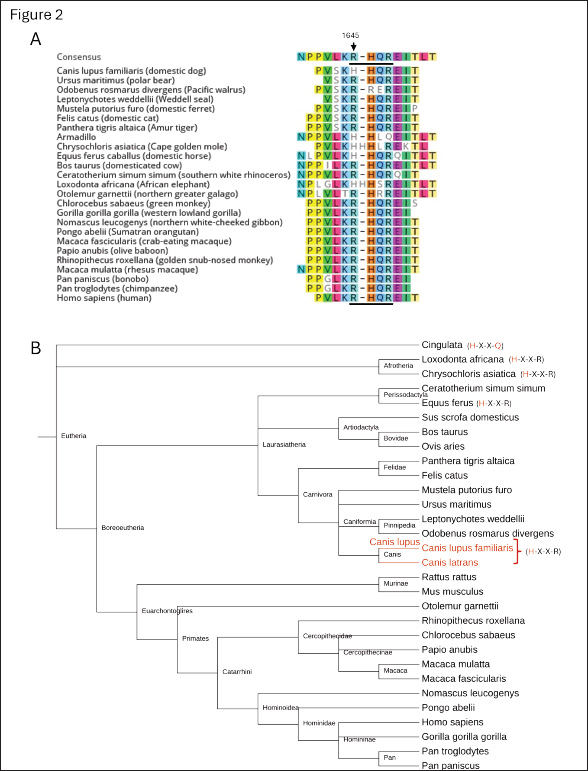

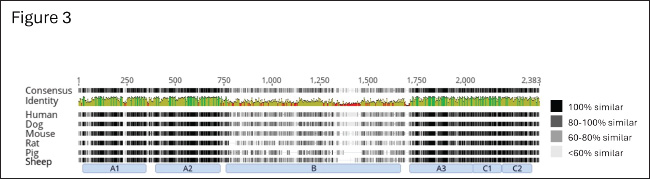

Fig. 1. Alignment of the amino acid and gene sequences of the furin-recognition site of FVIII in humans, hemophilia A animal models, and selected genus Canis species. (A) Previously reported amino acid sequences surrounding the furin-recognition motif (underlined) of FVIII in animal-models of hemophilia A: Homo sapiens (gi 182383), Canis lupus familiaris (gi 2645493), Mus musculus (gi 148697282), Rattus norvegicus (gi 34328534), Sus scrofa (gi 47523422), and Ovis aries (gi 284484541). (B) Newly determined gene sequences and predicted amino-acid sequences of F8 of Canis species and human control. Representative sequencing chromatograms are shown for human (Homo sapiens, n=1), domestic dog (C. lupus familiaris, n=12), gray wolf (C. lupus, n=12) and coyotes (C. latrans, n=10). The conservation of the unique H1645 across the genus Canis is identified within the box. Materials and MethodsGenomic DNA from free-ranging gray wolves was extracted from seven fresh blood samples (Barber-Meyer, 2021) using QIAamp Blood Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Gray wolves were live-captured using modified foot-hold traps (Livestock Protection Company’s EZ Grip 7) and released as part of a long-term wolf radio collaring study in the Superior National Forest, Minnesota, USA (48°N, 92°W) (Mech, 2009). The details on trapping, capture, and processing were previously reported (Barber-Meyer and Mech, 2014). In addition, five skeletal muscle specimens were obtained from carcasses. Domestic dog genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples from animals from the University of Pennsylvania Ryan Veterinary Hospital in Philadelphia (n=12). Coyote genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples (n=9) or stool samples (n=5). The latter DNA extraction was done using Macherey-Nagel Lts kit, (Bethlehem, PA) as per the manufacturer instructions. PCR product using degenerated primers for the amplification of the putative furin cleavage site at position 1313 (5’–TCAAAAATAAGGGAAGAAGC-3’ and 5-GTAGCAGGTTTAGAAGAGCA-3’) or at the position 1645 (5’-GAAGGCTTGGNAAATNAAAC-3’ and 5’-CGTGTTTTCTNTTGAAAGCTGCG-3’) was cloned in TOPO PCR cloning kits (Invitrogen, Nazareth, PA) into Top10 cells, and multiple colonies were sequenced for the selected product from each specimen. Genomic F8 DNA sequences from human and dog were used in NCBI blastp (National Center for Biotechnology Information protein-protein BLAST, Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (Altschul et al., 1990) searches to identify additional species genomic sequences. Alignment of nucleotide and amino acid sequences was carried out in Geneious Prime (Dotmatics, Auckland, New Zealand). A phylogenetic tree was generated with phyloT version 2 (phylot.biobyte.de, operated by Ivica Letunic, Heidelberg, Germany) based on NCBI taxonomy and visualized with iTOL: Interactive Tree of Life version 7.0 (https://itol.embl.de, designed and developed by biobyte solutions, Heidelberg, Germany) (Letunic and Bork, 2024). Ethical approvalThe guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for use of wild mammals in research were followed, and the capture of wild wolves was conducted under U. S. Fish and Wildlife permits PRT831774 and TE3886A-0 and the approval of the U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Animal Care and Use Committee. ResultsDNA analysis of the furin-recognition site at FVIII position 1645 in the Canis speciesThere are differences between hematologic and chemical parameters from free-ranging and captive wolves (Mech and Buhl, 2020; Thoresen et al., 2009). Therefore, we sought fresh blood samples for DNA analysis as a definitive source of genomic DNA data for the F8 gene, which is located on the Canis X chromosome as in humans. We obtained samples from free-ranging (wild) wolves, as these samples are unaffected by potential selective pressures due to human breeding in some captive wolves. All 10 X-chromosomes analyzed from 4 male and 3 female free-ranging gray wolves from northern Minnesota showed amino acid H1645 (Fig. 1B). The same results were also obtained from skeletal muscles of 1 male and 4 female wild gray wolf carcasses from elsewhere in Minnesota. Thus, 19 X chromosomes from 12 gray wolves from these regions were either hemi- or homozygous for H1645. Coyotes from Washington (2 males and 3 females), Alaska (2 males and 3 females), and Eastern Ontario, Canada (n=4, sex unknown) also only had the H1645 variant (Fig. 1B). Together, all 20+ X-chromosomes from 14 coyotes from 3 distinct geographic regions were hemi- or homozygous for H1645 by sequence analysis. Additionally, to confirm that selective breeding of domesticated dogs did not alter inheritance at this allele, the F8 gene was sequenced from 12 domestic dogs of unidentified sex representing at least 10 distinct breeds—including German shepherd, shar-pei, Portuguese water dog, cocker spaniel, Rhodesian ridgeback, Boston terrier, West Highland white terrier, English setter, Chihuahua and collie. All only had the H1645 variant (Fig. 1B). Protein alignment of the furin-recognition site at FVIII position 1645 in other mammalian speciesThe NCBI protein BLAST was used to identify and align the FVIII position 1645 furin-recognition site in other mammals. All primates whose sequences were publicly available through BLAST at the time of our search had the R1645 variant, as did all members of the order Carnivora and suborder Caniformia outside of the canids (Fig. 2). Interestingly, additional members of the class Mammalia were seen to have mutations in the R-X-X-R furin cleavage site at this location according to publicly available sequencing data (Fig. 2). These mutations likely arose independently. No diversion on the nucleotide sequence for the furin cleavage at position 1313There exists a second canonical furin cleavage site within the B-domain region that is lost during FVIII activation. Unlike at amino acid 1645, the sequence of the potential furin-cleavage site at position 1313 (R-X-X-R) was the same among humans, domestic dogs, gray wolves, and coyotes (data not shown). DiscussionWhile working with hemophilia A (HA) dogs as a preclinical model to develop a gene therapy treatment, we unexpectedly found a diversion (R1645H) of a consensus furin-cleavage site in dogs that was not present in any other non-dog species commonly used for hemophilia AHA preclinical studies (Siner et al., 2013; Siner et al., 2016). We thus sought to determine if this unique variant was present in additional members of the Canis genus or limited to the domestic dog. Genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism and haplotype assessment have clearly demonstrated that the ancestor of the domestic dog in North America is the gray wolf (Vonholdt et al., 2010). While the domestication of dogs from the gray wolf is well supported, there is an ongoing debate on the timing, location, and number of events that took place (Botigue et al., 2017; Bergstrom et al., 2020; Loog et al., 2020). To avoid sampling animals that had resulted from inadvertent admixture between wolves and domesticated dogs, we focused on free-ranging gray wolves in Minnesota rather than captured/bred or wolves living closer to human settlements. Sequences from 19 X chromosomes from 12 wild wolves sampled across the state all showed only the unique H1645 sequence, suggesting that the variation had arisen prior to the domestication of dogs. Moreover, the presence of only H1645 in coyotes from three distinct locations in North America further supports this hypothesis and indicates that the presence of H1645 in the sampled wolves is not purely the result of inadvertent breeding with dogs, but is common in the genus Canis. Our data also supports the converse: that the H1645 variant seen in domesticated dogs is not simply due to admixture of domestic dogs with wolves. At least 10 distinct breeds of domestic dogs, including modern breeds initiated in the Victorian period (circa year 1830), all had only the H1645 variant. Additional members of the Carnivora suborder Caniformia, which includes canids, whose FVIII sequences are publicly available through the NCBI BLAST include Ursus maritimus (polar bear), Odobenus rosmarus divergens (Pacific walrus), Leptonychotes weddellii (Weddell seal), and Mustela putorius furo (domestic ferret). Sequences from Carnivora Felis catus (domestic cat) and Panthera tigris altaica (Amur tiger) are also available. All these species maintained the R1645 and R-X-X-R motif (Fig. 2). Together, these findings suggest that the R1645H diversion evolved within the genus Canis before the separation of gray wolf and coyotes 1.8–2.5 million years ago (Nowak, 2003). Because both the wolf and coyote possess the H1645 diversion, presumably their ancestor would have too. Their ancestor has long been thought to be Canis lopophagus or Canis arnensis (Nowak, 2003). However, more recently, Gopalakrishnan et al. (2018) have hypothesized that the coyote and gray wolf genomes may contain a basal ancestral component derived from an as-yet-unidentified species that evolved after the divergence of the African hunting dog branch from the other canid species. If that hypothesis is correct, that suggests that the H1645 diversion could have occurred even earlier. To date, no variants have been identified at R1645 in humans that are associated with thrombophilia, though only two thrombophilic variants of FVIII have been described (Simioni et al., 2021; Wischmeyer et al., 2024). Given that R1645 is found within the B-domain, this is unsurprising, since missense mutations within this domain are predominantly polymorphisms and non-pathological (Ogata et al., 2011). What is surprising, though, is that there have been no other variants at all identified at position 1645 in humans, benign or otherwise (The UniProt Consortium, 2022). Much of the B domain is tolerant of single-nucleotide polymorphisms and highly variable and lacking in the cross-species homology seen in the FVIII A and C domains (Fig. 3), which makes the homology at R1645-1648 striking. It thus appears that there was evolutionary pressure to retain the R1645-1648 furin cleavage site in humans, carnivores, and many other mammals, but to lose it in members of the genus Canis. The role of H1645 FVIII in these Canis species remains to be determined. However, we have previously shown that canine FVIII is more efficiently expressed and secreted (Sabatino et al., 2009). This contrasts with the general assumption that furin cleavage sites are necessary for proteolytically cleavage of protein precursors into fully functional and better secreted proteins, as noted in other clotting factors (Siner et al., 2016). In the case of FVIII, the furin consensus cleavage site of human FVIII (Siner et al., 2016) and the over-expression of furin in cell lines expressing hFVIII (Plantier et al., 2005) are both inefficient for the generation of optimal protein biological activity. Thus, the H1645 FVIII variant may be at least partially responsible for the hypercoagulable state of dogs.

Fig. 2. The furin-recognition site of FVIII in mammalian species across the eutheria clade. (A) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the furin-recognition site of FVIII in various eutherians obtained from NCBI protein-protein BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). The amino acid position corresponding to 1645 in humans is indicated with the arrow and the furin-recognition site is underlined. (B) Phyologenetic tree of the species whose coagulation FVIII is included in part A, with deviations from the R-X-X-R furin-recognition site at 1645-1648 indicated in red text in the parentheses. Canis lupus familiaris, Canis lupus, and Canis latrans are indicated with red text. The tree was generated with phyloT version 2 based on NCBI taxonomy and visualized with iTOL: Interactive Tree of Life (Letunic and Bork, 2024).

Fig. 3. Amino acid alignment of full-length factor VIII among humans and hemophilia A animal models. The alignment of full-length coagulation factor VIII of Homo sapiens (gi 182383), Canis lupus familiaris (gi 2645493), Mus musculus (gi 148697282), Rattus norvegicus (gi 34328534), Sus scrofa (gi 47523422), and Ovis aries (gi 284484541) obtained from NCBI and UniProt (The UniProt Consortium, 2022). Shading indicates the level of homology, with 100% homology being black and less homology being progressively lighter. Domain structure shown below with lack of inter-species homology throughout the B-domain of factor VIII. ConclusionHere we have demonstrated that the conservation of H1645 within the furin cleavage site of canine FVIII is common to multiple breeds of dogs (C. lupus familiaris), their direct ancestor the gray wolf (C. lupus), and the closely related coyote (C. latrans), but not other members of the order Carnivora, suggesting this unique canid sequence evolved in a common ancestor under distinct evolutionary pressure from the high conserved R1645 variant seen in many other mammalian species. AcknowledgmentsWe are grateful for the critical collaborators that kindly provided animal samples: Dr. Carolin Humpal and Dr. Michelle Carstensen from Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (gray wolf carcasses), Dr. Linda Rutledge from Trent University and Dr. Bradley White from Natural Resources DNA Profiling and Forensic Center at Trent University, Ontario, Canada (Eastern coyotes), Dr. Mary Beth Callan, University of Pennsylvania (domestic dogs) and Dr. Laura R. Prugh, University of Washington (coyote samples from Washington and Alaska), and numerous U.S. Geological Survey volunteer field technicians that collected data and samples. We would also like to thank Nicolas Martin, Charlotte M. Guerra, and Taylor Daniel for technical assistance. We thank Ellen Heilhecker (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife) and Bhavya Doshi for their helpful reviews of our manuscript. Any mention of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. FundingVRA reported receiving NIH/NHLBI funding, R01 HL137335 (VRA), P01-HL139420 (Project 4 to VRA). Authorship contributionJMC and JIS performed the molecular studies, analyzed and assembled the data, and wrote the manuscript; SB-M and LDM provided guidance, samples from wild gray wolves, and wrote the manuscript; fieldwork and initial manuscript drafting were done while SB-M was with USGS; BSJ analyzed and assembled the data and wrote the manuscript; VRA designed the experiments, supervised the work, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript, but passed away prior to completion of the manuscript. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Data availabilityThe dataset is deposited into Dryad (DOI: 10.5061/dryad.t76hdr8b5). ReferencesAltschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W. and Lipman, D.J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. Barber-Meyer, S.M. 2021. The importance of wilderness to wolf (Canis lupus) survival and cause-specific mortality over 50 years. Biol. Conserv. 258, 109–145. Barber-Meyer, S.M. and Mech, L.. D. 2014. How hot is too hot? Live-trapped gray wolf rectal temperatures and 1-year survival. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 38, 762–772. Bashir, A., Li, S., Ye, Y., Zheng, Q., Knanghat, R., Bashir, F., Shah, N.N., Yang, D., Xue, M., Wang, H. and Zheng, C. 2024. SARS-CoV-2 S protein harbors furin cleavage site located in a short loop between antiparallel β-strand. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 281, 136020. Bergstrom, A., Frantz, L., Schmidt, R., Ersmark, E., Lebrasseur, O., Girdland-Flink, L., Lin, A.T., Stora, J., Sjogren, K.G., Anthony, D., Antipina, E., Amiri, S., Bar-Oz, G., Bazaliiskii, V.I., Bulatovic, J., Brown, D., Carmagnini, A., Davy, T., Fedorov, S., Fiore, I., Fulton, D., Germonpre, M., Haile, J., Irving-Pease, E.K., Jamieson, A., Janssens, L., Kirillova, I., Horwitz, L.K., Kuzmanovic-Cvetkovic, J., Kuzmin, Y., Losey, R.J., Dizdar, D.L., Mashkour, M., Novak, M., Onar, V., Orton, D., Pasaric, M., Radivojevic, M., Rajkovic, D., Roberts, B., Ryan, H., Sablin, M., Shidlovskiy, F., Stojanovic, I., Tagliacozzo, A., Trantalidou, K., Ullen, I., Villaluenga, A., Wapnish, P., Dobney, K., Gotherstrom, A., Linderholm, A., Dalen, L., Pinhasi, R., Larson, G. and Skoglund, P. 2020. Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science 370, 557–564. Botigue, L.R., Song, S., Scheu, A., Gopalan, S., Pendleton, A.L., Oetjens, M., Taravella, A.M., Seregely, T., Zeeb-Lanz, A., Arbogast, R.M., Bobo, D., Daly, K., Unterlander, M., Burger, J., Kidd, J.M. and Veeramah, K.R. 2017. Ancient European dog genomes reveal continuity since the Early Neolithic. Nat. Commun. 8, 16082. Cameron, C., Notley, C., Hoyle, S., Mcglynn, L., Hough, C., Kamisue, S., Giles, A. and Lillicrap, D. 1998. The canine factor VIII cDNA and 5’ flanking sequence. Thromb. Haemost. 79, 317–322. Elder, B., Lakich, D. and Gitschier, J. 1993. Sequence of the murine factor VIII cDNA. Genomics 16, 374–379. Gitschier, J., Wood, W.I., Goralka, T.M., Wion, K.L., Chen, E.Y., Eaton, D.H., Vehar, G.A., Capon, D.J. and Lawn, R.M. 1984. Characterization of the human factor VIII gene. Nature 312, 326–330. Gopalakrishnan, S., Sinding, M.S., Ramos-Madrigal, J., Niemann, J., Samaniego Castruita, J.A., Vieira, F.G., Caroe, C., Montero, M.M., Kuderna, L., Serres, A., Gonzalez-Basallote, V.M., Liu, Y.H., Wang, G.D., Marques-Bonet, T., Mirarab, S., Fernandes, C., Gaubert, P., Koepfli, K.P., Budd, J., Rueness, E.K., Sillero, C., Heide-Jorgensen, M.P., Petersen, B., Sicheritz-Ponten, T., Bachmann, L., Wiig, O., Hansen, A.J. and Gilbert, M.T.P. 2018. Interspecific gene flow shaped the evolution of the genus Canis. Curr. Biol. 28, 3441–3449.e5. Healey, J.F., Lubin, I.M. and Lollar, P. 1996. The cDNA and derived amino acid sequence of porcine factor VIII. Blood 88, 4209–4214. Hossain, M.G., Tang, Y.D., Akter, S. and Zheng, C. 2022. Roles of the polybasic furin cleavage site of spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 replication, pathogenesis, and host immune responses and vaccination. J. Med. Virol. 94, 1815–1820. Johnson, B.A., Xie, X., Bailey, A.L., Kalveram, B., Lokugamage, K.G., Muruato, A., Zou, J., Zhang, X., Juelich, T., Smith, J.K., Zhang, L., Bopp, N., Schindewolf, C., Vu, M., Vanderheiden, A., Winkler, E.S., Swetnam, D., Plante, J.A., Aguilar, P., Plante, K.S., Popov, V., Lee, B., Weaver, S.C., Suthar, M.S., Routh, A.L., Ren, P., Ku, Z., An, Z., Debbink, K., Diamond, M.S., Shi, P.Y., Freiberg, A.N. and Menachery, V.D. 2021. Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature 591, 293–299. Kaufman, R.J., Wasley, L.C. and Dorner, A.J. 1988. Synthesis, processing, and secretion of recombinant human factor VIII expressed in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 6352–6362. Letunic, I. and Bork, P. 2024. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82. Loog, L., Thalmann, O., Sinding, M. S., Schuenemann, V. J., Perri, A., Germonpre, M., Bocherens, H., Witt, K. E., Samaniego Castruita, J. A., Velasco, M. S., Lundstrom, I. K. C., Wales, N., Sonet, G., Frantz, L., Schroeder, H., Budd, J., Jimenez, E. L., Fedorov, S., Gasparyan, B., Kandel, A. W., Laznickova-Galetova, M., Napierala, H., Uerpmann, H. P., Nikolskiy, P. A., Pavlova, E. Y., Pitulko, V. V., Herzig, K. H., Malhi, R. S., Willerslev, E., Hansen, A. J., Dobney, K., Gilbert, M. T. P., Krause, J., Larson, G., Eriksson, A. and Manica, A. 2020. Ancient DNA suggests modern wolves trace their origin to a Late Pleistocene expansion from Beringia. Mol. Ecol. 29, 1596–1610. Mech, L. D. 2009. Long-term research on wolves in the Superior National Forest. In: Recovery of gray wolves in the great lakes region of the United States: an endangered species success story, Eds., Wydeven, A. P., Van Deelen, T. R. and Heske, E. J.. New York, NY: Springer, pp: 15–34. Mech, L.D. and Buhl, D.A. 2020. Seasonal cycles in hematology and body mass in free-ranging gray wolves (Canis lupus) from northeastern Minnesota, USA. J. Wildl. Dis. 56, 179–185. Nowak, R.M. 2003. Wolf evolution and taxonomy. In Wolves: Behavior, ecology, and conservation., Eds., L. D. Mech, L. D. and L. Boitani, L. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp: 239–258. Ogata, K., Selvaraj, S.R., Miao, H.Z. and Pipe, S.W. 2011. Most factor VIII B domain missense mutations are unlikely to be causative mutations for severe hemophilia A: implications for genotyping. J. Thromb. Haemost. 9, 1183–1190. Pipe, S.W. 2009. Functional roles of the factor VIII B domain. Haemophilia 15, 1187–1196. Pittman, D.D., Alderman, E.M., Tomkinson, K.N., Wang, J.H., Giles, A.R. and Kaufman, R.J. 1993. Biochemical, immunological, and in vivo functional characterization of B-domain-deleted factor VIII. Blood 81, 2925–2935. Plantier, J.L., Guillet, B., Ducasse, C., Enjolras, N., Rodriguez, M.H., Rolli, V. and Negrier, C. 2005. B-domain deleted factor VIII is aggregated and degraded through proteasomal and lysosomal pathways. Thromb. Haemost. 93, 824–32. Sabatino, D.E., Freguia, C.F., Toso, R., Santos, A., Merricks, E.P., Kazazian, H.H., Jr., Nichols, T.C., Camire, R.M. and Arruda, V.R. 2009. Recombinant canine B-domain-deleted FVIII exhibits high specific activity and is safe in the canine hemophilia A model. Blood 114, 4562–4565. Samelson-Jones, B. J. and Arruda, V. R. 2019. Protein-engineered coagulation factors for hemophilia gene therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 12, 184–201. Seidah, N.G. and Prat, A. 2012. The biology and therapeutic targeting of the proprotein convertases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 367–383. Simioni, P., Cagnin, S., Sartorello, F., Sales, G., Pagani, L., Bulato, C., Gavasso, S., Nuzzo, F., Chemello, F., Radu, C. M., Tormene, D., Spiezia, L., Hackeng, T. M., Campello, E. and Castoldi, E. 2021. Partial F8 gene duplication (factor VIII Padua) associated with high factor VIII levels and familial thrombophilia. Blood 137, 2383–2393. Siner, J.I., Iacobelli, N.P., Sabatino, D.E., Ivanciu, L., Zhou, S., Poncz, M., Camire, R.M. and Arruda, V.R. 2013. Minimal modification in the factor VIII B-domain sequence ameliorates the murine hemophilia A phenotype. Blood 121, 4396–4403. Siner, J.I., Samelson-Jones, B.J., Crudele, J.M., French, R.A., Lee, B.J., Zhou, S., Merricks, E., Raymer, R., Nichols, T.C., Camire, R.M. and Arruda, V.R. 2016. Circumventing furin enhances factor VIII biological activity and ameliorates bleeding phenotypes in hemophilia models. JCI Insight 1, e89371. The Uniprot Consortium 2022. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D523–D531. Thoresen, S.I., Arnemo, J.M. and Liberg, O. 2009. Hematology and serum clinical chemistry reference intervals for free-ranging Scandinavian gray wolves (Canis lupus). Vet. Clin. Pathol. 38, 224–229. Vonholdt, B.M., Pollinger, J.P., Lohmueller, K.E., Han, E., Parker, H.G., Quignon, P., Degenhardt, J.D., Boyko, A.R., Earl, D.A., Auton, A., Reynolds, A., Bryc, K., Brisbin, A., Knowles, J.C., Mosher, D.S., Spady, T.C., Elkahloun, A., Geffen, E., Pilot, M., Jedrzejewski, W., Greco, C., Randi, E., Bannasch, D., Wilton, A., Shearman, J., Musiani, M., Cargill, M., Jones, P.G., Qian, Z., Huang, W., Ding, Z.L., Zhang, Y.P., Bustamante, C.D., Ostrander, E.A., Novembre, J.and Wayne, R.K. 2010. Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature 464, 898–902. Wischmeyer, J., Baird, C., Grandvallet Contreras, J., Tran, A., Phang, T. and Manco-Johnson, M. 2024. A novel factor VIII mutation with increased activity, severe thrombosis and resistance to activated protein C. Blood 144, 135. Yu, C., Wang, G., Liu, Q., Zhai, J., Xue, M., Li, Q., Xian, Y. and Zheng, C. 2023. Host antiviral factors hijack furin to block SARS-CoV-2, ebola virus, and HIV-1 glycoproteins cleavage. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2164742. Zakas, P.M., Gangadharan, B., Almeida-Porada, G., Porada, C.D., Spencer, H.T. and Doering, C.B. 2012. Development and characterization of recombinant ovine coagulation factor VIII. PLoS One 7, e49481. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Siner JI, Barber-meyer S, Samelson-jones BJ, Mech LD, Arruda VR, Crudele JM. Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 Web Style Siner JI, Barber-meyer S, Samelson-jones BJ, Mech LD, Arruda VR, Crudele JM. Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=204709 [Access: January 12, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Siner JI, Barber-meyer S, Samelson-jones BJ, Mech LD, Arruda VR, Crudele JM. Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Siner JI, Barber-meyer S, Samelson-jones BJ, Mech LD, Arruda VR, Crudele JM. Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 12, 2026]; 15(7): 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 Harvard Style Siner, J. I., Barber-meyer, . S., Samelson-jones, . B. J., Mech, . L. D., Arruda, . V. R. & Crudele, . J. M. (2025) Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. Open Vet. J., 15 (7), 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 Turabian Style Siner, Joshua I., Shannon Barber-meyer, Benjamin J. Samelson-jones, Lucyan David Mech, Valder R. Arruda, and Julie M. Crudele. 2025. Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 Chicago Style Siner, Joshua I., Shannon Barber-meyer, Benjamin J. Samelson-jones, Lucyan David Mech, Valder R. Arruda, and Julie M. Crudele. "Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Siner, Joshua I., Shannon Barber-meyer, Benjamin J. Samelson-jones, Lucyan David Mech, Valder R. Arruda, and Julie M. Crudele. "Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene." Open Veterinary Journal 15.7 (2025), 3216-3222. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Siner, J. I., Barber-meyer, . S., Samelson-jones, . B. J., Mech, . L. D., Arruda, . V. R. & Crudele, . J. M. (2025) Ancient origin of the furin sequence in the wolf F8 gene. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3216-3222. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.32 |