| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3231-3239 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(7): 3231-3239 Research Article Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeonsAbdullah Ali Alkhalaf1, Waleed Rizk El-Ghareeb1*, Ahmed Meligy Abdelghany Meligy1, Hisham A. Ismail1, Walaa Fathy SaadEldin2, Abeer Fathy Ibrahim Hassan3 and Heba A. Baz31Department of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 2Central Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt 3Educational Veterinary Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt *Corresponding Author: Waleed Rizk El-Ghareeb. Department of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Al Hofuf, Saudi Arabia. Email: welsaid [at] kfu.edu.sa Submitted: 02/06/2025 Revised: 12/06/2025 Accepted: 15/06/2025 Published: 31/07/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

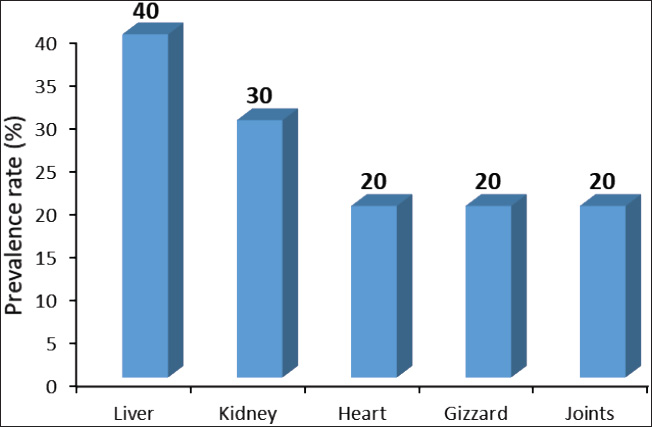

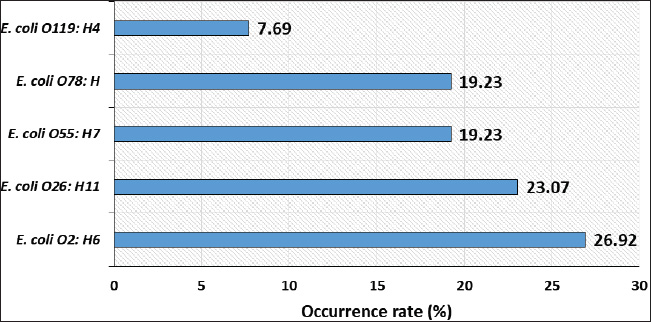

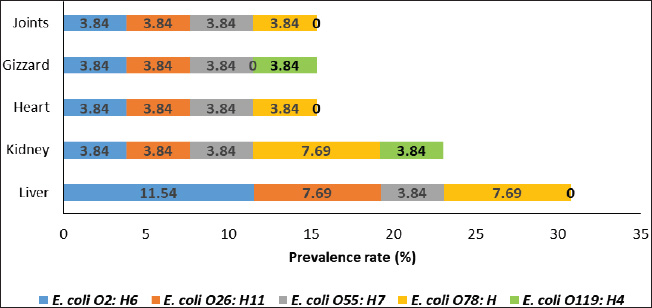

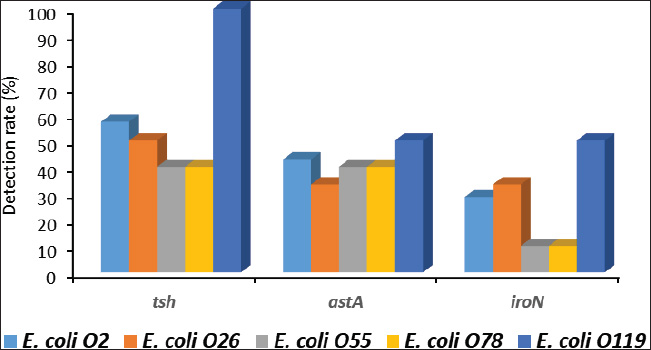

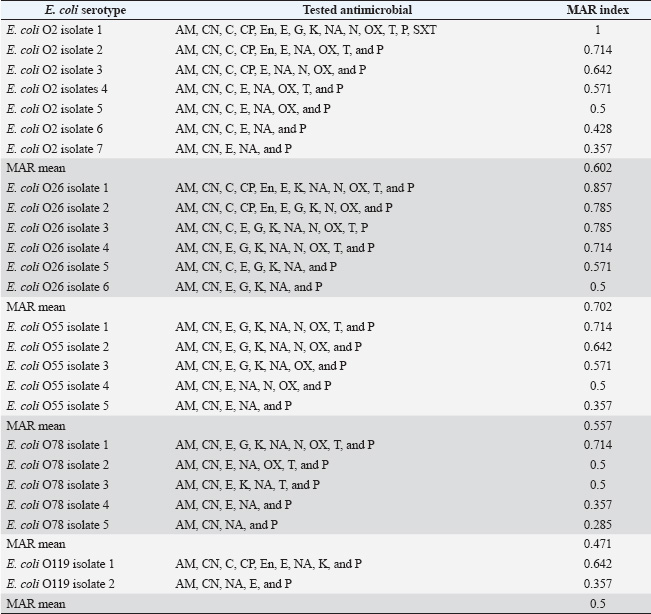

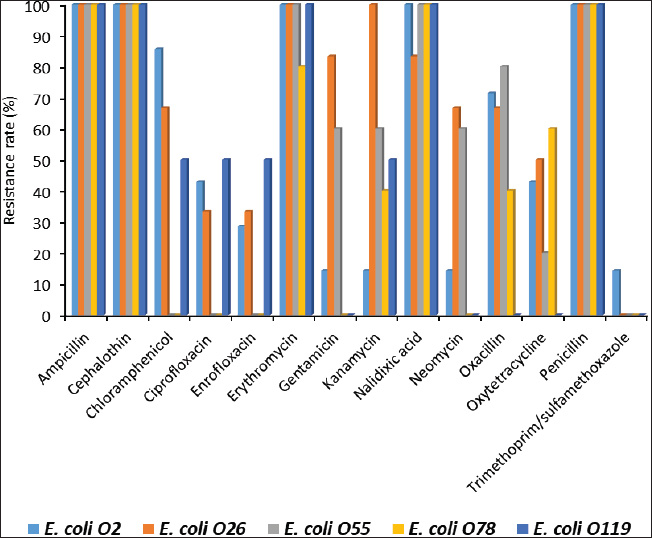

ABSTRACTBackground: Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) is a major threat because it can infect both domesticated and wild birds. Studies on the frequency of APEC in wild and migratory birds are scarce, especially compared with data on other bird species. The significance of the pigeon as a significant vector and reservoir of APEC transmission to other bird species was particularly neglected. Aim: This investigation was conducted with the express goal of examining whether or not the pigeon’s extraintestinal tissues contained multidrug-resistant APEC. Methods: Tissue specimens were collected from domesticated birds either freshly dead or in a moribund state and examined for the isolation and identification of E. coli using traditional culture methods, followed by serological identification. Screening for virulence-associated genes was performed using PCR. Included in this group of genes are astA, temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin (tsh), and iron outer membrane receptor (iroN). Drug resistance profiling was performed using the disk diffusion method. Results: The results recorded in this investigation revealed the isolation of E. coli at 40% from the examined pigeon samples. Isolation of E. coli from extraintestinal tissues was successful at 40%, 30%, 20%, 20%, and 20% from the examined liver, kidney, heart, gizzard, and joints, respectively. Serological identification of the isolated E. coli revealed serotyping of five serotypes, namely E. coli O2:H6, E. coli O26: H11, E. coli O55: H7, E. coli O78:H-, and E. coli O119:H4, which were recovered at 26.92%, 23.07%, 19.23%, 19.23%, and 7.69%, respectively. The recovered isolates harbored virulence attributes at variable rates. The recovered E. coli isolates should be marked with drug resistance, particularly to ampicillin, cephalothin, nalidixic acid, and penicillin. Conclusion: Consequently, the fact that pigeons could be multidrug-resistant APEC carriers should be seriously considered. Keywords: E. coli, Pigeons, Drug resistance, Virulence attributes, Prevalence. IntroductionIn Egypt and other countries, avian pathogenic Escherichia coli poses a serious threat to the poultry industry. Many pigeon diseases, including colibacillosis, omphalitis, cellulitis, coligranuloma, and yolk sac infection, are caused by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) strains (Salehi and Ghanbarpour, 2010). It is clear, however, that data on the incidence of E. coli infections outside the intestines in pigeons are lacking. Extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli, or ExPEC, relies on several virulence-associated components to reduce the host immune response and increase bacterial invasion, colonization, and spread (Ghanbarpour et al., 2010). Many parts of the globe, such as Egypt, Italy, and China, consider pigeons particularly popular birds. Pigeon meat is eaten not only at weddings and banquets, but it is also a specialty at several Chinese restaurants. Because it is softer, more juicier, and more flavorful than most common bird cuts, pigeon meat is often considered a delicacy. Because most of the meat is concentrated in the breast, the amount of meat produced per bird is rather tiny. Similar to duck skin, pigeon flesh is black and the skin is fatty. The flesh is 17.5% protein, contains a ton of minerals and vitamins, is easy to digest, and contains very little fat (Andrew, 2006; US. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2013). Pigeons may act as potential carriers of several bacterial species. These include Salmonella spp., Campylobacter, E. coli, and Chlamydia (Lillehaug et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2005). Pigeons can be found in live-bird markets, poultry farms, and people’s homes. Pigeon droppings are a major vector of disease transmission in homes and live-bird markets where these birds are kept. According to Santaniello et al. 2007, pigeons not only carry the E. coli bacterium but also effectively spread it to other animals and humans. Pigeons may therefore be a possible reservoir for antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. Due to the overuse of antibiotics in veterinary medicine and, more specifically, on poultry farms, multidrug-resistant pathogens have emerged, making it extremely difficult to control and prevent bacterial diseases. This has far-reaching consequences for both the poultry industry and public health, as infected products can be consumed by anyone (Darwish et al., 2013). According to Alsayeqh et al. 2022, birds can carry and transmit antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pathogen strains that can harm both people and animals. Key bacterial infections have shown an upsurge in antibiotic resistance (Parry and Threlfall, 2008). Numerous animal species are bred for meat; however, they are potential sources of pathogens such as E. coli. Taking all these factors into consideration, the current study aimed to determine how common ExPEC was in pigeons presenting with colibacillosis symptoms. After the isolation of E. coli, further serological identification was performed on the samples. Three genes associated with virulence were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. The genes in question were the outer membrane receptor arginine succinyltransferase and tsh. This study also used the disk-diffusion method to examine the antibiotic resistance patterns of the different E. coli serotypes that were identified. Materials and MethodsThe collection of specimensWe collected 100 specimens from 20 domesticated pigeons that were either moribund or had recently died between July and December 2024. These specimens included 20 of each of the following: heart, lungs, liver, gizzards, and joints. These pigeons were collected during their visits to the Educational Veterinary Hospital, which is a component of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Zagazig University in Egypt, or private veterinary clinics. The pigeon age varied from 1 to 4 months. Diarrhea is associated with lack of appetite, respiratory distress, and poor growth in birds. Air sacculitis, pericarditis, perihepatitis, peritonitis, and erosion on the gizzards were identified during necropsy. Specimens were immediately forwarded to the Laboratory of Microbiology at the Educational Veterinary Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt. Bacteriological examinationThe tissue samples were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours after being directly plated on MacConkey agar plates (Difco, Detroit, Michigan). Lactose-fermenting colonies were re-inoculated onto eosin methylene blue agar plates (Difco, Detroit, Michigan,). A metallic appearance, a dark purple center, and a greenish appearance were among the characteristics of typical E. coli colonies. The colonies were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and subsequently stored at 4°C in order to facilitate further identification. They were then inserted into Nutrient agar slants. The staining and biochemical assays employed to identify the isolates were conducted in accordance with the methodology that was previously published (Cloud et al., 1985). Serodiagnosis of E. coliIn order to diagnose the enteropathogenic types of E. coli, the confirmed isolates were identified using rapid diagnostic E. coli antisera sets (Difco, Detroit, Michigan) (Kok et al., 1996). DNA extractionBacterial DNA was identified in each glycerol stock. The E. coli sero-diagnosis was conducted in accordance with the procedure previously described (Ghanbarpour et al., 2010). Nanodrop (ND-1000, Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, Delaware) was used to determine the concentration of DNA in the supernatant. Identification of the virulence attributes by the use of PCRThe presence or absence of several virulence-associated genes, including tsh, astA, and iroN, was examined in the tested E. coli with PCR. The primer sets used were ordered, as mentioned by Ibrahim (2019). For amplification, a thermal cycler—more specifically, a Master cycler made by Eppendorf of Hamburg, Germany—was employed. Following the protocol established by Dhanashree and Mallya (2008), PCR assays were conducted. An Eppendorf thermal cycler (Hamburg, Germany) was used for the amplification process. The amplified DNA fragments were subjected to an examination using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (AppliChem, Germany, GmbH). Using a UV transilluminator, the gel was collected after being colored with ethidium bromide. Using a DNA ladder longer than 100 base pairs served as the marker. The positive control strain E. coli O157:H7 Sakai and the nonpathogenic negative control strain, E. coli K12DH5α, were assigned as the reference strains. Antibiograms of the recovered E. coli serotypesFor this study, we used the disk diffusion method to examine the antibiotic resistance profiles of the E. coli serotypes that were recovered, following the guidelines laid out by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (2013). The zones of inhibition widths of the tested strains and the antimicrobial disks used for their testing were both performed in compliance with the standards laid out by CLSI (2013). The testing process included fourteen different antimicrobials. The following antimicrobials were used: ampicillin, ceftiofur, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, lincomycin, nalidixic acid, neomycin, oxytetracycline, penicillin, polymixin B, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT). To determine the antimicrobial inhibition zones, we used rulers and interpreted the data according to the CLSI (2013) standard. Ethical approvalThis study was conducted according to the guidelines of Zagazig University, Egypt, and the study received approval number ZU-IACUC/2/F/42/2024. ResultsThe results of this investigation revealed the isolation of E. coli at 40% from the examined pigeon samples. Isolation of E. coli from the extraintestinal tissues was successful at concentrations of 40%, 30%, 20%, 20%, and 20% from the examined liver, kidney, heart, gizzard, and joints, respectively (Fig. 1). According to the results of the serological analysis of the E. coli that was isolated, serotyping was performed on five different serotypes. These serotypes were as follows: E. coli O2:H6, E. coli O26: H11, E. coli O55: H7, E. coli O78:H-, and E. coli O119:H4. These serotypes were recovered at 26.92%, 23.07%, 19.23%, 19.23%, and 7.69%, respectively (Fig. 2. E. coli O2: H6 had the highest prevalence in the liver (11.54%). It was also identified in the other examined tissues at 3. 3.84%. E. coli O26: H11 came second in the prevalence at the liver (7.69%), and also recovered at 3.84% from the other examined tissues. E. coli O55: H7 was equally isolated from the different tissues at 3.84%. E. coli O78:H- was recovered from both the liver and the kidney at 7.69% and from the heart and joints at 3.84%. E. coli O119:H4 was only identified from the kidney and the gizzard samples at 3.84% (Fig. 3). The data presented in Figure 4 show the detection rates of the screened virulence genes among the recovered E. coli serotypes. The tsh gene was detected in E. coli O2:H6, E. coli O26: H11, E. coli O55: H7, E. coli O78:H-, and E. coli O119:H4 at 57.12%, 50%, 40%, 40%, and 100%, respectively, while the astA gene was detected in these pathotypes at 42.84%, 33.32%, 40%, 40%, and 50%, respectively, but the iroN gene was detected at 28.56%, 33.32%, 10%, 10%, and 50%, respectively. The AMR profiling of the recovered E. coli isolates is presented in Table 1 and Figure 5. E. coli O2:H6 isolates showed complete resistance (100%) to ampicillin, cephalothin, erythromycin, nalidixic acid, and penicillin. Lower resistance (14.28%) was apparent to gentamicin, kanamycin, neomycin, and trimethoprim/SXT, respectively. E. coli O26: H11 was 100% resistant to ampicillin, cephalothin, erythromycin, kanamycin, and penicillin; and marked sensitivity (33.32%) to ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin. E. coli O55: H7 isolates showed 100% resistance to ampicillin, cephalothin, erythromycin, nalidixic acid, and penicillin and high sensitivity (100%) to ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/SXT. The isolates of E. coli O78:H- showed 100% resistance to ampicillin, cephalothin, nalidixic acid, and penicillin and high sensitivity (100%) to ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, neomycin, and trimethoprim/SXT. E. coli O119:H4 isolates showed complete resistance to ampicillin, cephalothin, erythromycin, nalidixic acid, and penicillin and complete sensitivity to gentamicin, neomycin, oxacillin, oxytetracycline, and trimethoprim/SXT. DiscussionPigeons represent a PROMISING source of high-quality animal protein. The pigeon, either domesticated or wild, might be at the same time a potential source of infectious agents such as E. coli. In the current investigation, E. coli was isolated from extraintestinal tissues at an overall prevalence rate of 40%. This rate is lower than that reported by Dutta et al. (2013), who isolated E. coli from pigeons at 60.67% in India. Besides, Karim et al. (2020) isolated E. coli at 52.5% from pigeons in Bangladesh. Postmortem lesions such as fibrinous perihepatitis, pericarditis, enteritis, and pneumonia corroborate the spread of E. coli to many organs, including the heart, lungs, and liver, suggesting that E. coli caused septicemia and the subsequent deaths of birds (Kabir, 2010). The finding that E. coli can spread to other parts of the body is in line with what Darwish et al. (2015) found a high incidence of the bacteria in duck giblets and meat. Chickens and turkeys raised in Brazil were found to have E. coli in several organs and tissues, including the spleen, liver, kidneys, trachea, lungs, skin, ovary, oviduct, intestine, and cloaca (De Carli et al., 2015). Cloud et al. (1985) noted that avian colibacillosis is commonly linked to E. coli O2, O35, and O78. In agreement with the results of the present study, Dutta et al. (2013) identified several E. coli serotypes, including O2, O157, O68, O121, O9, O75, O131, O13, and O22. The virulence characteristics that help bacteria colonize new areas, spread to other organs, and develop resistance to antibiotics are hallmarks of E. coli strains that cause illness in birds. According to Dho-Moulin and Fairbrother (1999), colibacillosis-associated E. coli strains typically express these genes. Among these, avian-pathogenic E. coli O78 was the initial locus for the discovery of tsh, a protein belonging to the autotransporter family. This virulent factor is highly pathogenic and deadly in strains that express it (Dozois et al., 2000). Lesion development and fibrin deposition in the bird’s air sacs are aided by the protein tsh (tsh gene autotransporter), which also demonstrates mucinolytic activity, cleaves casein, and may be associated with air sacculitis, pericarditis, perihepatitis, and peritonitis (Henderson et al., 1998). According to the findings of this investigation, the tsh expression was detected in the E. coli pathotypes that were recovered. Consistent with previous research, this finding confirms that E. coli O1, O2, and O78 are fatal to 1-day-old chicks because of their TSH virulence factors. Furthermore, Darwish et al. (2015) found that E. coli O26, O78, O86, O1145, and O127, which were isolated from various duck organs, expressed the tsh virulence factor. Different bacteria use arginine for various purposes, including nitrogen, carbon, and energy. The astA gene is the primary mechanism for arginine catabolism in E. coli. Schneller et al. (1998) found that E. coli isolates with overexpressed astA grew and multiplied more quickly. Similarly, the extremely pathogenic E. coli strain O157 has an overexpression of astA (Shirai and Mizuguchi, 2003). It is highly probable that astA was present in E. coli O78, O86, and O114 that were extracted from various duck tissues (Darwish et al., 2015). Another dangerous component is the iroN, which plays a key role in biofilm development in the ExPEC serogroup and determines iron intake and pathogenicity, particularly in enteropathogenic E. coli species (Magistro et al., 2015). Escherichia coli O26, O78, O86, O114, and O127 were among the E. coli strains found to express iroN that had been recovered from various duck organs (Darwish et al., 2015).

Fig. 1. Prevalence rate (%) of E. coli among different extraintestinal tissues of the examined pigeons.

Fig. 2. Occurrence rates (%) of different E. coli serotypes recovered from the extraintestinal tissues of the examined pigeons.

Fig. 3. Distribution of different E. coli serotypes in the examined pigeon tissues.

Fig. 4. Detection rate (%) of the tested virulence genes among the recovered E. coli serotypes from the examined pigeon specimens. Table 1. Antimicrobial resistance profiling of the recovered E. coli serotypes.

Poultry farms’ overuse of antibiotics has given rise to bacteria resistant to these drugs, making it far more difficult to prevent and control bacterial illnesses (Darwish et al., 2013). Based on the data, it is evident that certain E. coli serotypes are highly sensitive to certain antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, neomycin, and enrofloxacin, whereas others, like ampicillin, erythromycin, penicillin, and nalidixic acid, are clearly resistant. Dutta et al. 2013 reported that among the antibiotics tested, 91 (or 100% of the isolates) were resistant to ampicillin, 73.62% to nitrofurantoin, 65.93% to tetracycline, 62.63% to oxytetracycline, and 61.54% to streptomycin. Farghaly et al. 2017 also discovered that E. coli O20, O78, and O127 isolated from quails showed strong resistance to amoxicillin (71.4%), ciprofloxacin (57.1%), and nalidixic acid (57.1%). These findings are consistent with these findings. Furthermore, when E. coli serotypes O78 and 127 were recovered from duck giblets, Darwish et al. 2015 discovered that these strains were resistant to amoxicillin but highly sensitive to cefotaxime and norfloxacin. Tests against E. coli bacteria revealed that amoxicillin, ampicillin, azithromycin, erythromycin, nalidixic acid, gentamicin, and tetracycline were ineffective. Levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin did not show any signs of E. coli resistance either (Karim et al., 2020). The extensive and excessive use of antibiotics in chicken farms may have contributed to the emergence of resistant E. coli bacteria. Pigeon farms should minimize the abuse of antibiotics and institute strict sanitary protocols to guarantee the safety of this essential meat source. Future research should focus on determining whether recovered E. coli serotypes express genes associated with antibiotic resistance.

Fig. 5. Antimicrobial resistance rates (%) of tested antimicrobials among recovered E. coli serotypes in this study. ConclusionThis study found that E. coli infection was common in Egyptian pigeons, with the liver being the site of infection at the greatest frequency. The most common serotypes of E. coli were O2, O26, O55, O78, and O119. This group of harmful serotypes harbored virulence-promoting genes, such as tsh, astA, and iroN. Several antibiotics routinely used in Egyptian chicken farming have been shown to have strong resistance to the discovered E. coli. Nevertheless, ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, neomycin, and enrofloxacin are among the most promising options for pigeon E. coli infection control. AcknowledgmentsThe authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Project# KFU251829). Conflicts of interestThe authors have not declared any conflict of interest. FundingThe authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Project# KFU251829). Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed equally. Data availabilityAll data were presented in the study. ReferencesAlsayeqh, A.F., Baz, A.H.A. and Darwish, W.S. 2021. Antimicrobial-resistant foodborne pathogens in the Middle East: a systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(48), 68111–68133. Andrew, D.B. 2006. Pigeons: the fascinating saga of the world’s most revered and reviled bird. Grove Press, NY: Open City Books. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI Approved Standard M100-S23. Cloud, S.S., Rosenberger, J.K., Fries, P.A., Wilson, R.A. and Odor, E.M. 1985. In vitro and in vivo characterization of avian Escherichia coli. I. Serotypes, metabolic activity, and antibiotic sensitivity. Avian Dis. 29(4), 1084–1093. Darwish, W.S., Eldaly, E., El-Abbasy, M., Ikenaka, Y. and Ishizuka, M. 2013. Antibiotic residues in food: African scenario. Jap. J. Vet. Res. 61, S13–S22. Darwish, W.S., Saad Eldin, W.F. and Eldesoky, K.I. 2015. Prevalence, molecular characterization and antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolated from duck meat and giblets. J. Food Safety 35, 410–415. De Carli, S., Ikuta, N., Lehmann, F. K., da Silveira, V. P., de Melo Predebon, G., Fonseca, A.S. and Lunge, V.R. 2015. Virulence gene content in Escherichia coli isolates from poultry flocks with clinical signs of colibacillosis in Brazil. Poult. Sci. 94(11), 2635–2640. Dhanashree, B. and Mallya, S. 2008. Detection of shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) in diarrhoeagenic stool and meat samples in Mangalore, India. Indian J. Med. Res. 128, 271–277. Dho-Moulin, M. and Fairbrother J.M. 1999. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Vet. Res. 30, 299–316. Dozois, C.M., Dho-Moulin, M., Brée, A., Fairbrother, J.M., Desautels, C. and Curtiss, R. 3rd. 2000. Relationship between the Tsh autotransporter and pathogenicity of avian Escherichia coli and localization and analysis of the Tsh genetic region. Infect. Immun. 68(7), 4145–4154. Dutta, P., Borah, M.K., Sarmah, R. and Gangil, R. 2013. Isolation, histopathology and antibiogram of Escherichia coli from pigeons (Columba livia). Vet. World 6(2), 91–94. Farghaly, E.M., Samy, A. and Roshdy, H. 2017. Wide prevalence of critically important antibiotic resistance in Egyptian quail farms with mixed infections. Vet. Sci. Res. Rev. 3(1), 17–24. Ghanbarpour, R., Salehi, M. and Oswald, E. 2010. Virulence genotyping of Escherichia coli isolates from avian cellulitis in relation to phylogeny. Comp. Clin. Path. 19(2), 147–153. Henderson, I.R., Navarro-Garcia F. and Nataro J.P. 1998. The great escape: structure and function of the autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol. 6, 370–378. Ibrahim, W.F. 2019. Isolation, identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of recent E. coli serotypes from Japanese quails reared in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt. Damanhour J. Vet. Sci. 1(2), 14–17. Kabir, S. 2010. Avian colibacillosis and salmonellosis: a closer look at epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, control and public health concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 7, 89–114. Karim, S.J.I., Islam, M., Sikder, T., Rubaya, R., Halder, J. and Alam, J. 2020. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. isolated from pigeons. Vet. World 13(10), 2156. Kok, T., Worswich, D. and Gowans, E. 1996. Some serological techniques for microbial and viral infections. In Practical medical microbiology, 14th ed. Eds., Collee, J., Fraser, A., Marmion, B. and Simmons, A. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone, pp: 179–204. Lillehaug, A., Jonassen, C.M., Bergsjø, B., Hofshagen, M., Tharaldsen, J., Nesse, L.L. and Handeland, K. 2005. Screening of feral pigeon (Colomba livia), mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) and graylag goose (Anser anser) populations for Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., avian influenza virus and avian paramyxovirus. Acta Vet. Scand. 46, 1–10. Magistro, G., Hoffmann, C. and Schubert, S. 2015. The salmochelin receptor IroN itself, but not salmochelin-mediated iron uptake promotes biofilm formation in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC). Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 305(4–5), 435–445. Parry, C.M. and Threlfall, E.J. 2008. Antimicrobial resistance in typhoidal and nontyphoidal salmonellae. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 21(5), 531–538. Salehi, M. and Ghanbarpour, R. 2010. Phenotypic and genotypic properties of Escherichia coli isolated from colisepticemic cases of Japanese quail. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 42(7), 1497–1504. Santaniello, A., Gargiulo, A., Borrelli, L., Dipineto, L., Cuomo, A., Sensale, M., Fontanella, M., Calabria, M., Musella, V., Francesca Menna, L. and Fioretti, A. 2007. Survey of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157: H7 in urban pigeons (Columba livia) in the city of Napoli, Italy. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 6(3), 313–316. Schneider, B.L., Kiupakis, A.K. and Reitzer, L.J. 1998. Arginine catabolism and the arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180(16), 4278–4286. Shirai, H. and Mizuguchi, K. 2003. Prediction of the structure and function of AstA and AstB, the first two enzymes of the arginine succinyltransferase pathway of arginine catabolism. FEBS Lett. 555(3), 505–510. Tanaka, C., Miyazawa, T., Watarai, M. and Ishiguro, N. 2005. Bacteriological survey of feces from feral pigeons in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 67(9), 951–953. US. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2013. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 27. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home. Available via http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/960 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Alkhalaf AA, El-ghareeb WR, Meligy AMA, Ismail HA, Saadeldin WF, Hassan AFI, Baz HA. Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 Web Style Alkhalaf AA, El-ghareeb WR, Meligy AMA, Ismail HA, Saadeldin WF, Hassan AFI, Baz HA. Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=262426 [Access: January 12, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Alkhalaf AA, El-ghareeb WR, Meligy AMA, Ismail HA, Saadeldin WF, Hassan AFI, Baz HA. Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(7): 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Alkhalaf AA, El-ghareeb WR, Meligy AMA, Ismail HA, Saadeldin WF, Hassan AFI, Baz HA. Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 12, 2026]; 15(7): 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 Harvard Style Alkhalaf, A. A., El-ghareeb, . W. R., Meligy, . A. M. A., Ismail, . H. A., Saadeldin, . W. F., Hassan, . A. F. I. & Baz, . H. A. (2025) Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. Open Vet. J., 15 (7), 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 Turabian Style Alkhalaf, Abdullah Ali, Waleed Rizk El-ghareeb, Ahmed Meligy Abdelghany Meligy, Hisham A. Ismail, Walaa Fathy Saadeldin, Abeer Fathy Ibrahim Hassan, and Heba A. Baz. 2025. Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 Chicago Style Alkhalaf, Abdullah Ali, Waleed Rizk El-ghareeb, Ahmed Meligy Abdelghany Meligy, Hisham A. Ismail, Walaa Fathy Saadeldin, Abeer Fathy Ibrahim Hassan, and Heba A. Baz. "Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Alkhalaf, Abdullah Ali, Waleed Rizk El-ghareeb, Ahmed Meligy Abdelghany Meligy, Hisham A. Ismail, Walaa Fathy Saadeldin, Abeer Fathy Ibrahim Hassan, and Heba A. Baz. "Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons." Open Veterinary Journal 15.7 (2025), 3231-3239. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Alkhalaf, A. A., El-ghareeb, . W. R., Meligy, . A. M. A., Ismail, . H. A., Saadeldin, . W. F., Hassan, . A. F. I. & Baz, . H. A. (2025) Prevalence, antibiogram, and virulence attributes of avian pathogenic E. coli in pigeons. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (7), 3231-3239. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i7.34 |